The movie theaters of Colon Street are fading people’s palaces

Just as Avenida Rizal in Santa Cruz was the chief street on which business and entertainment in Manila were concentrated from the 1930s to the 1970s, so was Colon Street for Cebu City from the 1910s until the 1990s.

Colon Street has the distinction of being the oldest street in the Philippines. It dates back from the time when Cebu was the first colonial capital from 1565 to 1567, before the capital was moved to Iloilo, and then Manila. It was the administrative center of Spanish domains in the Visayas, Mindanao and the western Pacific— all the way to the Marianas, in fact.

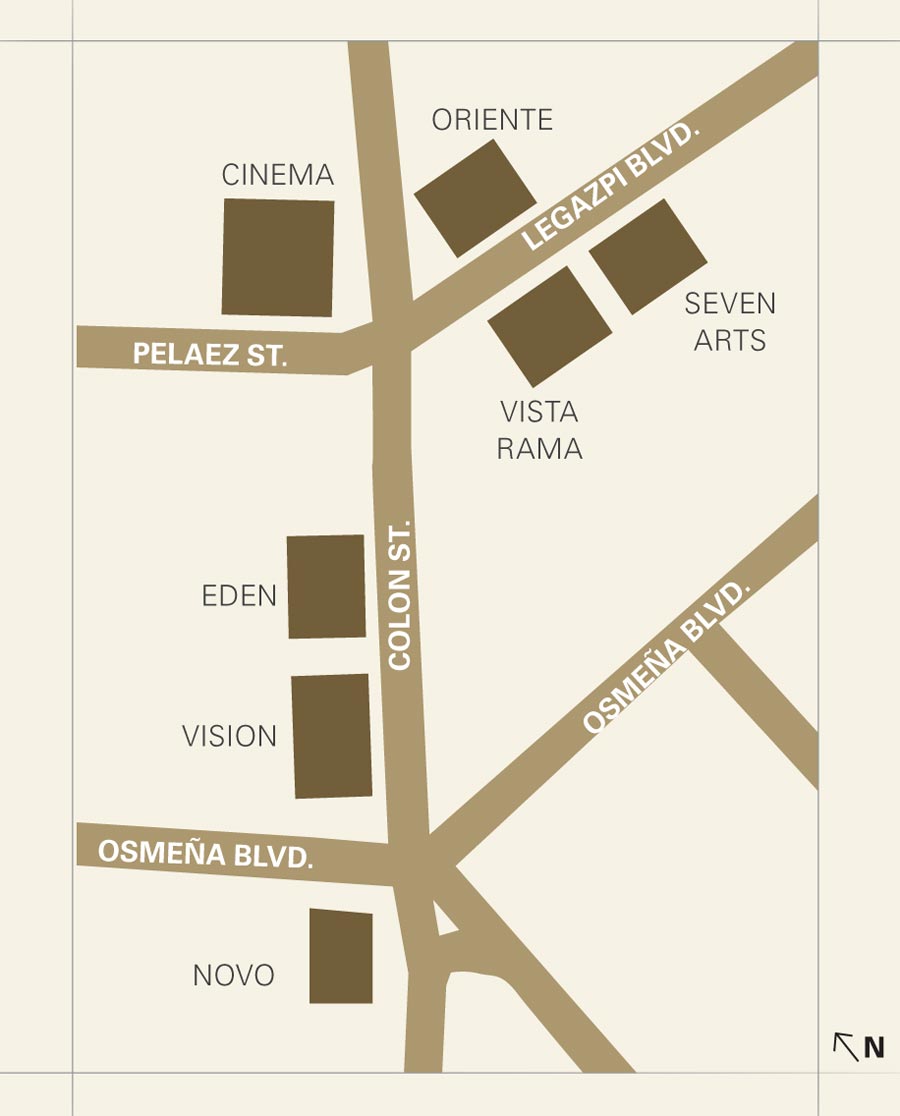

Cebu City’s old core of buildings and residential blocks were built according to the grid layout of the Recopilacion de las Islas, and it was bound on the northwest by a long, diagonal road named after explorer Christopher Columbus—Colon being the Hispanicized name of Columbus. The 1873 Escondrillas Map shows Colon as a meandering northeast-to-southwest margin of the city, beyond which was blank space— the uncultivated realengas where few Spaniards dared walk by themselves at night.

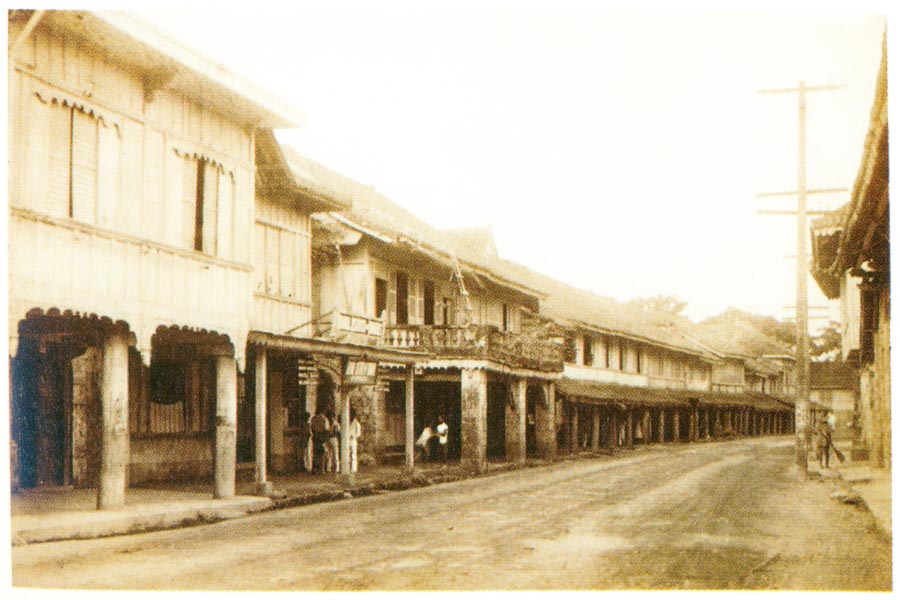

Separating urbanidad from the indio-dominated interior, Colon also served as the convenient meeting point at which produce from the uplands flowed into the city through the two-storey shop houses known as accessorias, owned and manned by enterprising Chinese mestizos who intermarried with the Spaniards and indios, and formed the economic backbone of the city.

READ MORE: Pobs before the pubs: Poblacion heritage you need to know

The accessorias were joined together to form long arcades that stretched the entire length of the street by the early 1900s, as can be seen in old photographs. With their shaded shop fronts of tile and mahogany posts, and pedestrian pavements of piedra china or coral stone faced in lime plaster, old Colon was like a scene from an early Western movie set in the tropics, the unpaved street alive with horse-drawn tartanillas, water buffalo carts, and coolies pulling passenger rickshaws and hauling produce.

The Cebuano mestizo families who made their fortunes in the nearby port, and established the social life of the city also took part in the evolution of Colon into Cebu’s business hub by the beginning of the 20th century. Among them was Don Jose Avila (1854-1959), who along with Vicente Sotto I founded Cebu’s first newspaper, The Cebu Advertiser in 1920. Avila also served several governors as Provincial Secretary from the 1900s-1930s (thus his appellation “the little governor”). He was responsible for planting the original mango trees that used to grace Mango Avenue (now Gen. Maxilom Avenue).

Working with American architects (most likely Daniel K. Bourne and William Parsons, respectively), Avila supervised the design and erection of Plaza Independencia and Plaza Rizal in the city core. It was Don Jose Avila who bought out the old Teatro Junquera from its original American owner at Colon corner Legazpi Street in the early 1930s, remodeled it, and renamed it Cinema Oriente. In addition, he also bought out another cinema house, Empire Theater, from its owners, which he paid for in kind with a Mercedes Benz motorized karwahe.

Later on, with business booming, Don Jose would also put up Vision Theater. The war put a temporary halt to cinema building, and Oriente was razed along with most of the city during the aerial bombings just before Liberation in March 1945. The concrete-shelled Vision Theater was the sole survivor of that battle. The Avilas rebuilt Oriente after the war, and under Don Jose’s son, Atty. Jesus “Lindong” Avila (who became the largest movie operator of Cebu in the late 60s) successfully reconstructed their cinema empire.

The Avilas would operate three cinemas after the war: Oriente, Ideal and Rizal. Aside from the Avilas, Chinese-Filipino families were the other major operators of Colon movie houses: the Yaps for Cinema, the Shos for President, and the Hos for Ultra Vistarama. The 1930s was the beginning of the golden age of cinema in the Philippines, more so in Cebu, where an English-educated public that still had strong affinities for the local Cebuano, as well as the Spanish spoken by its elite, thronged to the entertainment strip that was Colon.

These cinema houses evolved from older zarzuwela theaters (just like Teatro Zorilla in Manila), and also served as venues for boxing matches. With the advent of sound, Cebuano cinemas became more specialized affairs, and closely followed cinema theater design not only of Manila, but also of the continental US. Thus, in Colon Street, one can see the progression of grand cinema houses that mirrored the architectural tastes from the late-1920s into the postwar years: Neoclassicism for the 20s, Art Deco from the 30s to early 50s, and International Style from the mid-50s to the early 70s.

What is interesting about these Colon theaters is that they were apparently designed and built by local architects. Valeriano “Bobit” Avila, grandson of Don Jose, recounts that the postwar reconstruction of Oriente in the early 1950s was supervised by Gregorio Segura, who redesigned it with its now-familiar “wedding cake” curved façade in the Art Deco persuasion. Oriente’s façade is characterized by its large embossed rosettes that punctuate the series of spaces nestled within a five-paneled vertical screen frame, spaced in between stylized cornstalk dividers, with the cinema’s concrete marquee gracing its attic in large Sans Serif font.

READ MORE: The Mornings After: Escolta Block Parties are more than one-night affairs

Located just a block away from Santo Niño Basilica, Oriente fed on the crowds that moved from “uptown,” where the Capitol building and Fuente Osmeña are, to “downtown,” where the churches, the Carbon Public Market, and the all-important Pier were located. During its heyday, Oriente showed first-run Hollywood films from the MGM and Warner Brothers studios. The few Cebuano films made in the 50s were also screened there. Starting in the 70s, when Lindong Avila started to run FPJ’s films, Filipino became a major focus for Oriente. It was also in Oriente that Bobit Avila himself promoted Sharon Cuneta’s films.

The general decline of cinema audiences since the 80s has meant that Oriente would be transformed to other uses. Currently, it has been appropriated into the Colonnade Mall and supermarket that occupies the rest of the downtown block. But the Avilas, who still own the lot, are planning to revive it as a digital screening theater, which may mean partitioning its auditorium into two smaller theaters without destroying its distinctive façade.

The story of Colon’s cinema houses parallels to a large degree the decay experienced in downtown Manila. With the migration of cinema audiences to larger, newer cinemas ensconced inside super malls (starting with Robinson’s Cebu in the mid-1980s, and accelerating with SM City Cebu in the late 1990s), Cebu’s downtown has been left to the attentions of innercity vice, cheap thrills, and general decrepitude.

The fact that they are still standing, and that some of their owners still value them, speaks a lot about the Cebuano’s passion for preserving the architectural legacy of their forefathers. Time will tell if Cebu can save its old cinema houses at Colon Street from its own push for development, and exploit its historical uniqueness as a blueprint for a downtown revival. ![]()

This article first appeared in BluPrint Vol 3 2013. Edits were made for Bluprint online.

Photographed by Ed Simon