Fuji Kindergarten in Japan was designed with a healthy dose of danger

Prescribing danger to a piece of architecture for children, getting away with it, and then winning a slew of awards is all in a day’s work for Japanese architect Takaharu Tezuka. He spoke at the National Architecture Symposium: Evolving Paradigms organized by the architecture students of the University of Santo Tomas last April 23, 2016. His presentation came as a surprise. “A small dosage of danger is always needed,” he says as he shows how his projects almost always rebel against the stringent regulations in his country.

The world is a circle

Tezuka’s Fuji Kindergarten in Tokyo, completed in 2007, takes an oval form with the roof designed as an activity space for children. With just guardrails surrounding the roof and nets covering the spaces where three trees pierce through, the students find themselves in a rather entertaining playground. It’s not the safest place for the children but they sure are enjoying and learning. Tezuka took things further by designing classrooms without walls at the ground level, allowing children to loiter and interact with their schoolmates. They’re free to leave their classes anytime and roam around the courtyard at the center or climb up the roof. Tezuka quips, “It’s circular. They’ll eventually come around.” Although this is not in line with regulations for school buildings, he talked to people, explained his progressive concept, and managed to get his design approved.

Tezuka hopes the building will help develop the nursery school children’s physical, emotional, and social skills, which he finds lacking in an enclosed and overprotective society. He believes humans are hardwired for the outdoors, can easily adapt to their environment, and should not be deprived of the opportunities to do so.

“Here, the children can climb up the trees. Naturally, they get good at it! My son is capable of diving quite deep in the sea, and he is still 10 years old. He can swim a few kilometers, no problem. The most important thing is we let children explore their surroundings,” he says.

Ring Around a Tree

Asked to create an annex for the Fuji Kindergarten that functions as a classroom and a waiting area, Tezuka got his own children to “test” and play inside the open-air structure built around a mature Zelkova tree. And play they did– they ran around, crawled through the nooks and compartments, and climbed the tree. They sustained minor bumps and bruises with all the horseplay, which prompted Tezuka to adjust some parts of the structure to make it safer for other children. If it is safe enough for his children, then it is safe enough for others.

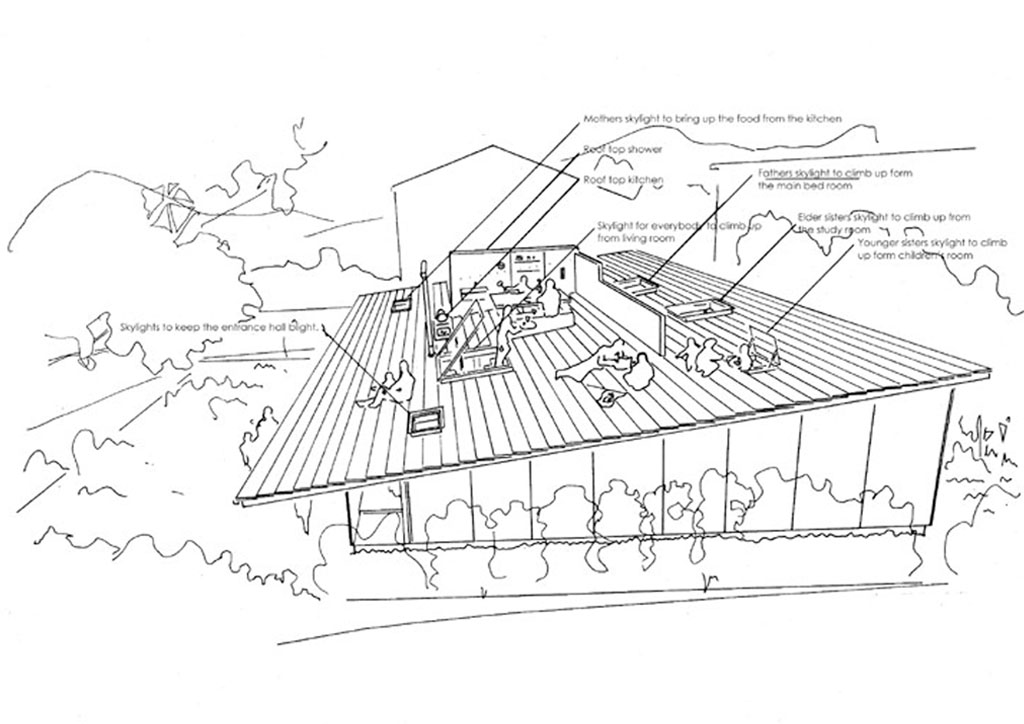

Up on the Roof

The nursery school was not the first instance Tezuka challenged convention. The Roof House–which Tezuka claims is the most photographed and featured house in Japan–is perhaps the project that started it all, as he acceded to his clients’ peculiar love for hanging out on the roof, virtually making it their alfresco living space. Located in Kanagawa Prefecture, the family house has a dining area, a kitchen, and even a shower on its roof. Each bedroom on the ground floor has its own access to the roof via ladder and skylight. He inclined the roof not only for rainwater discharge but also because inclines are more intuitive.

He points out that the best public squares like the Pompidou Center in Paris are inclined because people tend to stay at the sides and away from the middle of flat squares.

People-Centric Design

Tezuka’s architecture is difficult to imagine without people. All designs are done with specific people in mind. “The key is context–how people like the space and want to live in it,” he explains. Indeed, his Roof House would not make sense for a different client. His willingness to break convention (yet somehow always get approval) to delight the users of his buildings can be attributed to how much he values people. “It’s very important to talk to people. It’s called democracy,” says Tezuka. He shares his experience talking to politicians and organizations for disabled people whenever he can. He says “You can’t solve the problem by yourself. You need to find and talk to the right people.”

Whereas most designers comply with building regulations without a second thought, Tezuka is more inclined to free people from excessive restrictions. “If you see something wrong with the regulations, it is important to fight it,” exclaims Tezuka. He has no illusions that his designs can “achieve a hundred percent satisfaction,” much less please everyone. For this reason, although he champions making buildings and public spaces completely barrier-free or accessible, boldly stating that universal design can be boring and alienating. “I was talking to a colleague in Bali who said he doesn’t want to make barrier-free cities anymore. For him, it’s nice to have stairs without ramps and lifts. In Bali, they carry and assist the elderly or disabled. These people–total strangers– watch out for and care for one another. In a barrier-free city, you don’t need to care for people around you. Each person goes his own way. Of course, you can’t ignore accessibility all the time, but I think it’s important to find balance,” says Tezuka. For him, seeing people help those with disabilities is a more potent way to advocate for the plight of those with special needs. “Architecture is what makes human beings human,” Tezuka claims with conviction.

In the arena of architecture where performance and parametricism have gained solid footing, Tezuka goes beyond by sticking to the basics. As with most Japanese architects, Tezuka remains minimal not only with his aesthetic but also with the simple motivations that drive his design. This focus on purpose and program rather than form is a quality he shares with this mentor Richard Rogers. Takaharu Tezuka’s architecture reminds us that as humans and designers, we are free to question and break the rules when needed, learn from our errors, and discover other ways of doing small things. According to Tezuka, “small doses of danger are necessary because people need to fall sometimes so they will learn to get back up and learn to help one another.

This article first appeared in BluPrint Vol 4 2016. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

Photographed by Jonas Aarre Sommarset

READ MORE: Ned Carlos designs the Don Bosco Bi-Centennial School Building