Activating Interior Space and Light

SoFA Design Institute is a young college. Although we are growing rapidly and successfully, there are milestones we assumed might be beyond our immediate reach. When Berlin-based design think tank Metropolitan Laboratory, in partnership with the German/Austrian lighting manufacturer Zumtobel, invited us to participate in an international lighting design competition, we were thrilled to test our studio approach against global standards. As the only Asian participant, we would be compared with programs in Europe, North and South America and Africa—and thus felt a special obligation to represent the Philippines with distinction.

The competition, prosaically titled The Workspace Lighting Project: Influences on the Office Environment, was part of a range of symposia, exhibitions and workshops that consider how emerging technologies will invite improvement in contemporary design. I mentored the competition research with lighting designer and co-professor Jinky de Jesus. Together, we tried to stimulate concepts that consider light as more than illumination.

Educators have mixed feelings about bringing competitions into the classroom. Benefits accrue when joining a larger community to collectively mine a range of solutions to a given problem. Additionally, the prospect of winning a prize may stimulate greater effort by students. However, allowing competition sponsors to effectively dictate the structure, subject, focus and timing of a design studio is a direct challenge to the autonomy of the teacher. Moreover, this competition was focused on enhancing options for white collar, information workers—a privileged cohort within the labor community. We would have preferred to develop a critique, through design, of the manufacturing or agriculture sectors where the health, safety, comfort and welfare of the worker is often of less concern. In the end, we embraced the competition on its own terms while insulating our academic core by positioning the studio as a special offering open to all members of the design community.

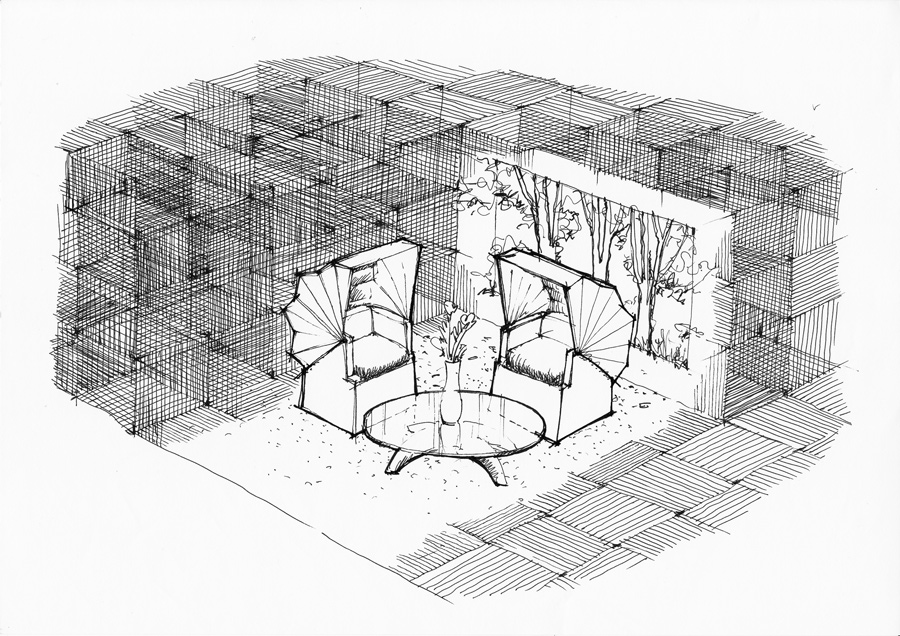

An early insight by the class—that light is only one form of electromagnetism (that portion of the spectrum visible to the human eye)—helped propel the dynamics of the probe. Additional uses of these energies, from radio waves and lasers to ultraviolet and infrared radiation, informed speculation about where designers could take the inventory of lighting related options. Light in the context of health seemed of particular interest to the students, and we focused our energies in a critique of light as a manipulable phenomenon which, when paired with technology, could expand its significance within the constructed environment.

READ MORE: A Brief History of the Design Competition

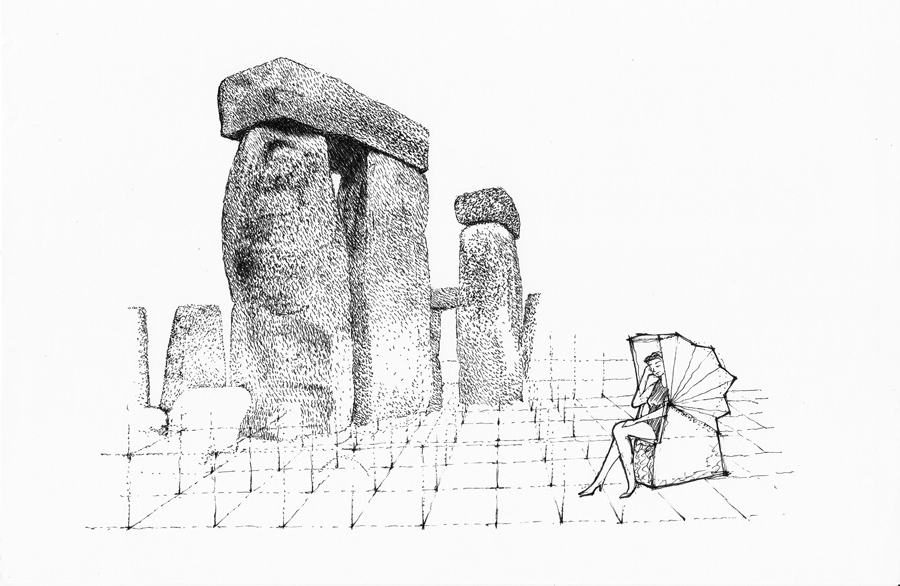

One implication of the competition brief concerned the primacy of the tangible. In normative building design, concept evolves into fruition—from paper to reality, via bricks and mortar. Because space and envelope are delineated with materials and assemblies, entire vocabularies are assigned to the stuff of construction. Seminal movements in design, Modernism chief among them, are predicated on this collective literacy. It is perhaps for this reason that Reyner Banham titled his history of Modernism as Theory and Design in the First Machine Age, implying that an industrial aesthetic of straight edges and smooth surfaces defined the dominant character of his subject. Similarly, the American historian, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, titled his reference on Frank Lloyd Wright, In the Nature of Materials, to suggest how a unique grammar of physicality was central to that architect’s canon.

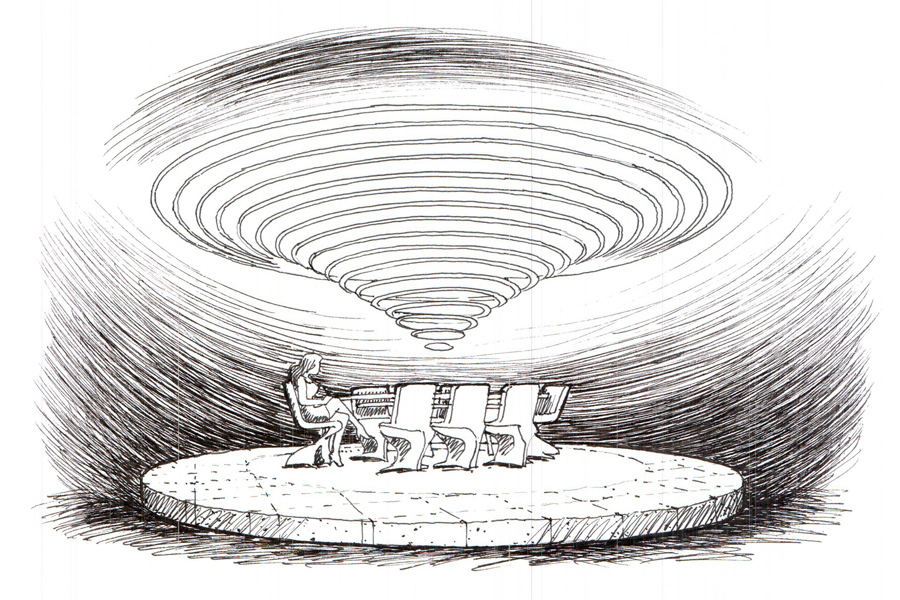

What if, the students wondered, light challenged this supremacy of substance when it came to defining, ordering and characterizing space, assuming a range of responsibilities nominally reserved to traditional elements of building like form, circulation and enclosure? What would Louis Kahn, the liege who commanded materials to speak, think about this? He who once rhapsodized:

“All material in nature,

the mountains and the streams and the air and we,

are made of Light which has been spent,

and this crumpled mass called material casts a shadow,

and the shadow belongs to Light.”

Architects and designers largely depend on the marketplace to deliver the innovative products that make the realization of our work possible. The construction industry would virtually grind to a halt if critical components had to be invented afresh with each new project. The global marketplace is ever more efficient in offering excellent parts and pieces of which we assemble into our designs.

By the same token, we cannot absolve ourselves, neither individually nor collectively, of the responsibility of inventing or, at the very least, imagining new approaches to buildings, spaces, and the discrete assemblies and technologies by which we bring our ideas to life.

To move in this direction, we might learn from our friends in industrial design. Architects, by definition, craft unique solutions, prototypes doomed to a production of one. Our work is focused entirely upon the needs of the individual client. The industrial designer is, by contrast, liberated from this tyrant, free to service a benevolent and forgiving amalgam of humanity. This significant distinction calls into question the extent to which the architect should be involved in product-based R&D. Is building design, itself a kind of research, sufficient, or should a broader obligation be mandated? The question of whether we should impose upon ourselves a broader role should be central to our self-definition. The studio considered both sides of this debate in the context of lighting innovation.

Many, perhaps most, designs are not destined to become the thing envisioned. All the vicissitudes of life determine with a blind randomness the fate of those scratches on the vellum or the pixels in the monitor. But, if we can exploit both the persistence of vision and a gullible imagination, which believes that which it sees, an entirely new universe becomes possible—a universe of true lies. Freed from the tyranny of necessity, liberated from weight and gravity, luminosity can unmoor us from place and time. Projected architecture—light architecture—may thus divorce design from the concerns of constructed reality. The promise of tele-immersion and virtual reality may transport us closer to the world of art, a destination architects have long dreamed of.

“Many, perhaps most, designs are not destined to become the thing envisioned. All the vicissitudes of life determine with a blind randomness the fate of those scratches on the vellum or the pixels in the monitor.”

In the end, we were left to consider how to balance that which we know with that to which we aspire. In lighting, there is considerable tension between these poles, especially given the rapid technological advances that challenge our everyday experiences. If images can be projected into the air, and our monitors can manipulate millions of color options, when electromagnetic energy can be processed and translated into other forms of energy, the relevance of what we know and what we do with that knowledge is questioned.

The revolution underway in design can ultimately be described in generational terms, where the digitally immersed, media-besotted youth are significantly advantaged. Having effectively obliterated the distinction between time and space, where proximity is an unnecessary precursor to intimacy, younger designers are creating a 4th dimension wherein to live and work. Whether by texting or sexting, gaming or Facebooking, theirs is a SimCity whose inhabitants are increasingly unconcerned with the traditional semiology of authenticity. In our studio, we had a murky glimpse of their future metropolis abuilding—a new Jerusalem powered by light. ![]()

This story first appeared in BluPrint Volume 2, 2015. Edits were made for Bluprint.ph.