Architectural photographs (or the remains of our buildings)

Architectural photographs today are kicked around cyberspace, swiped and scrolled on touchscreens, reacted to and commented on instantly, the vast majority of which forgotten as quickly as they are uploaded. By constantly feeding our insatiable appetite for new project images in ever shrinking timeframes in which to comprehend their meaning, we influence the cultural value of photos.

In many cases, their inherent worth is not so much diminished as they are overlooked. They are published with the thrill of being seen first or being the latest rather than aiming for a timelessness at the heart of every great architectural photograph. This contradicts the fundamental purpose they were taken in the first place—to uphold an architect’s optimism for a different way of living. It is only when we stop and look closely at how a photographer has framed a spatial scene that we begin to understand architecture’s yearning for permanence.

In searching for the essence of why it is imperative for architecture to be documented, we encounter a question of an image’s power as an agent for awareness. The crafted and considered architectural photo gives vital information about a project’s construction, its experienced materiality, its inhabitation, and also the thousands of decisions made during its gestation. The deeper into history a building goes the more effective a photo can be in safeguarding the most accurate truth about what a building stood for at the time it was built.

Few photos of demolitions have a more chapter-defining edge about them as the stills of the Pruitt-Igoe apartments in the US city of St. Louis, Missouri being blown up in the mid-1970s. When the first stage of demolition was over on July 15, 1972, historian Charles Jencks proclaimed it as the day “Modern architecture died”.

In the Philippines, the insidious nonchalance and apathy indirectly sprouting from a lack of credible architectural documentation leads to an unfulfilled closure, never mind the possibility of resurrection. By the time everyone is able to reconcile with the loss, another seemingly irrevocable execution occurs. Leandro V. Locsin must hold the record for the most number of buildings wiped from existence for a National Artist. Modernism has died several deaths in Metro Manila. Pages are being burned before anyone even has a chance to continue the story.

Dominic Galicia’s periodical call outs on Facebook about verifying the condition of the latest heritage building to face the wrecking ball reinforces this deficiency in public awareness. The halted demolition of the Philbanking Corporation Building, happening at the same time as the destruction of The Capitol Theater—designed by National Artists José Ma. Zaragoza and Juan Nakpil, respectively—represents the latest double whammy for the country’s burgeoning heritage conservation efforts. Netizens share their own photos from their own detective work to revive the discourse—unfortunately, as is too often the case, at a point when the sand has all but slipped through the hour glass.

The photographic image confirms its importance to society and, in turn, legitimizes the grave sense of injustice we feel when they are slated for demolition. We can do more to save these structures. And photographs can aid us in being the ammunition we need to fight the forces that undermine integral parts of the country’s history.

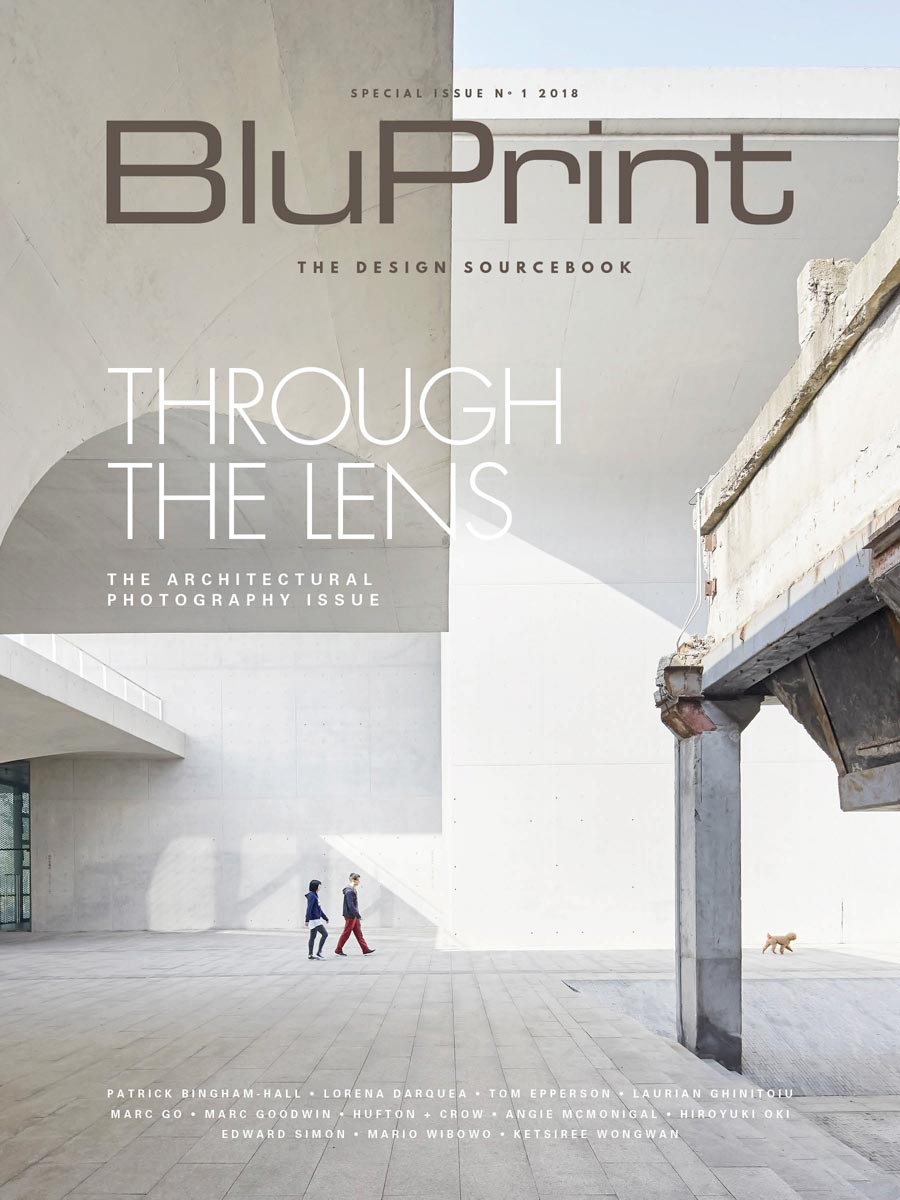

In BluPrint’s first Special Issue of the year we hear the stories behind the numerous approaches to architectural photography directly from the best image makers from across the world. We identify the project photos included by the year they were taken, not when they were completed, to stress that architecture does not stop when the architect steps away. They have done as much as any in the profession to preserve every architect’s aspiration to create a tangible legacy.

BluPrint Special Issue 1, 2018 is available in digital format via Flip100, and in newsstands and bookstores today. Cover photo by Hufton + Crow