Escolta Maestros: 6 Filipino architects who shaped the old CBD

The book, Ang Mundo ni Maestro, in its editing stage, features eleven Filipino master builders and architect pioneers spanning the 1850s to the 1970s.

The word maestro was used in the title because the book is also a tribute to the unheralded Filipino designers and builders in the Spanish colonial days, when the highest title an indio could aspire to in the building trade was maestro de obras, or master builder (similar to the construction foreman of today); while the insulares and peninsulares, whether artist-architect, priest-builder or military engineer, all carried the title director de obras (director of construction).

Many of the Filipino maestro de obras, who were much more than mere foremen, remain unknown and unrecognized. The few whose names managed to escape oblivion are Geronimo Tongco and Pedro Jusepe, who designed the walls of Intramuros in 1591; Nicolas Ruiz, who designed the Paco Cemetery in 1822; Severo Sacramento, the façade of Morong Church in 1853; and Luis Arellano, the Pinaglabanan church in San Juan in the 1880s.

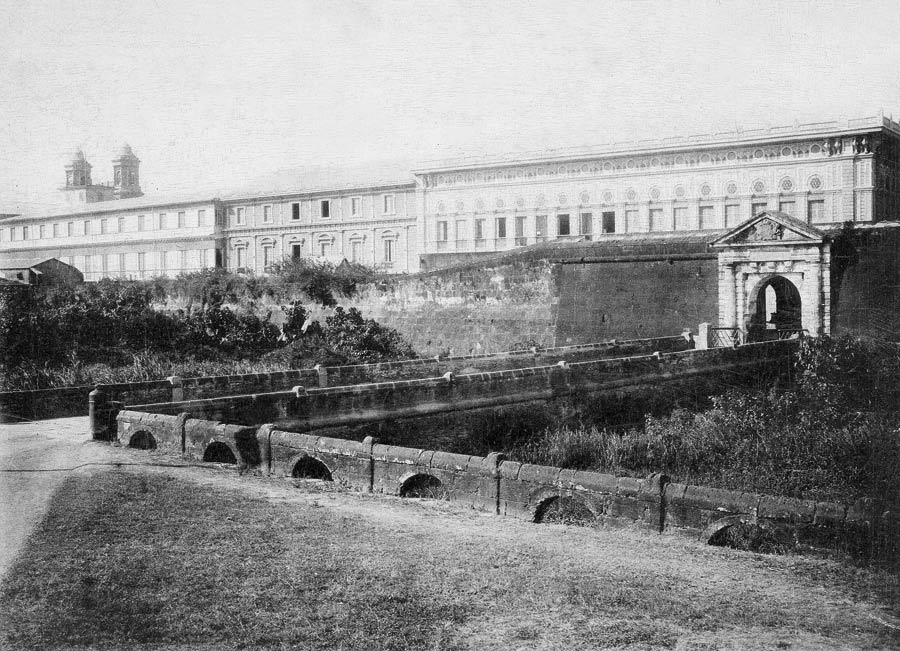

In the mid-19th century, Felix Rojas y Arroyo became the first Filipino to acquire a degree in architecture abroad. Upon returning from his travels and studies in Asia and Europe, he was assigned as Arquitecto Municipal de Manila (Municipal Architect), and eventually Director de Obras Publicas (Director of Public Works) in 1865. Rojas was the first Filipino to have broken through the Spanish ‘glass ceiling,’ and it is with his story that the book, Ang Mundo ni Maestro, begins.

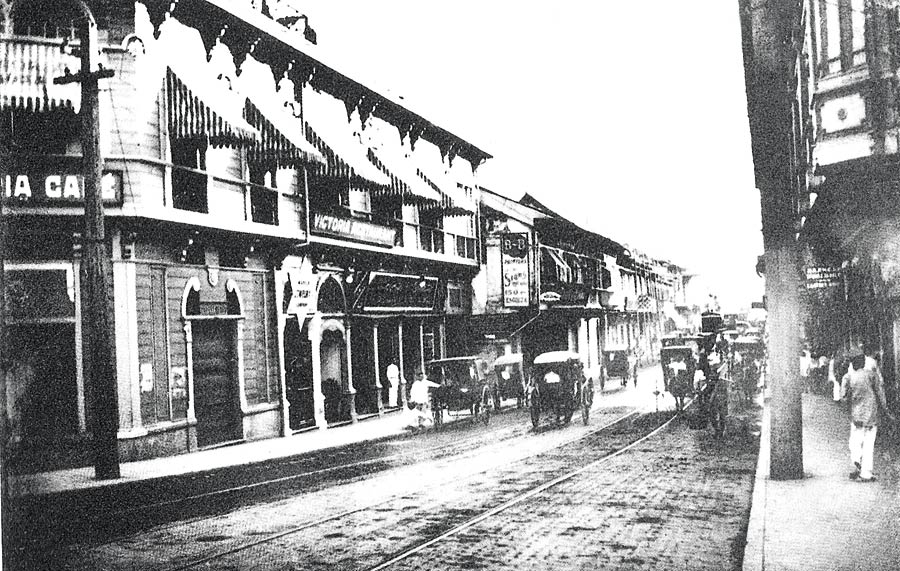

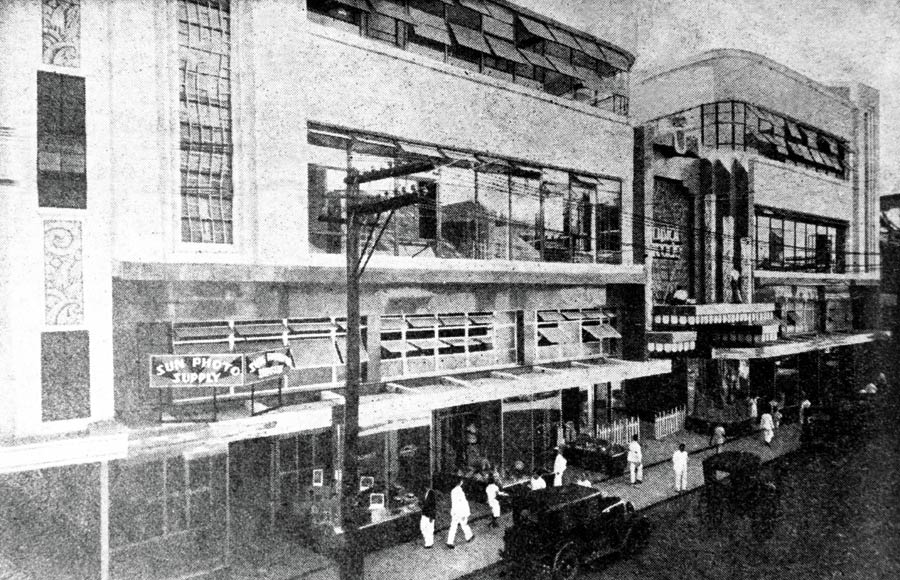

Editor’s note: This article was first published in BluPrint Special Issue 3 2013. Here we bring you a summery featuring the different maestros who shaped the old Escolta business district we wish we saw, the remnants of which are now being crumbled by time or met by the swings of bulldozers.

READ MORE: Architectural photographs (or the remains of our buildings)

Felix Arroyo Rojas (1823-1887)

Rojas belonged to a wealthy and influential clan in Manila—what they called buena familia. According to Joel Rico, Rojas acquired his government position after his aunt wrote the queen of Spain. The endorsement letter extolled his illustrious lineage, international exposure, academic training at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid, and above all, his competence and dedication to practice architecture in his native country.

Rojas proved more than qualified, designing public structures from watchtowers to markets, from schools to hospitals to administrative buildings like customs houses and tribunal courts. As head of public works, he also carried out civil works such as canals (traffic in Manila at that time was at the Pasig River, not on land), as well as zoning programs for the fire plagued districts of Manila.

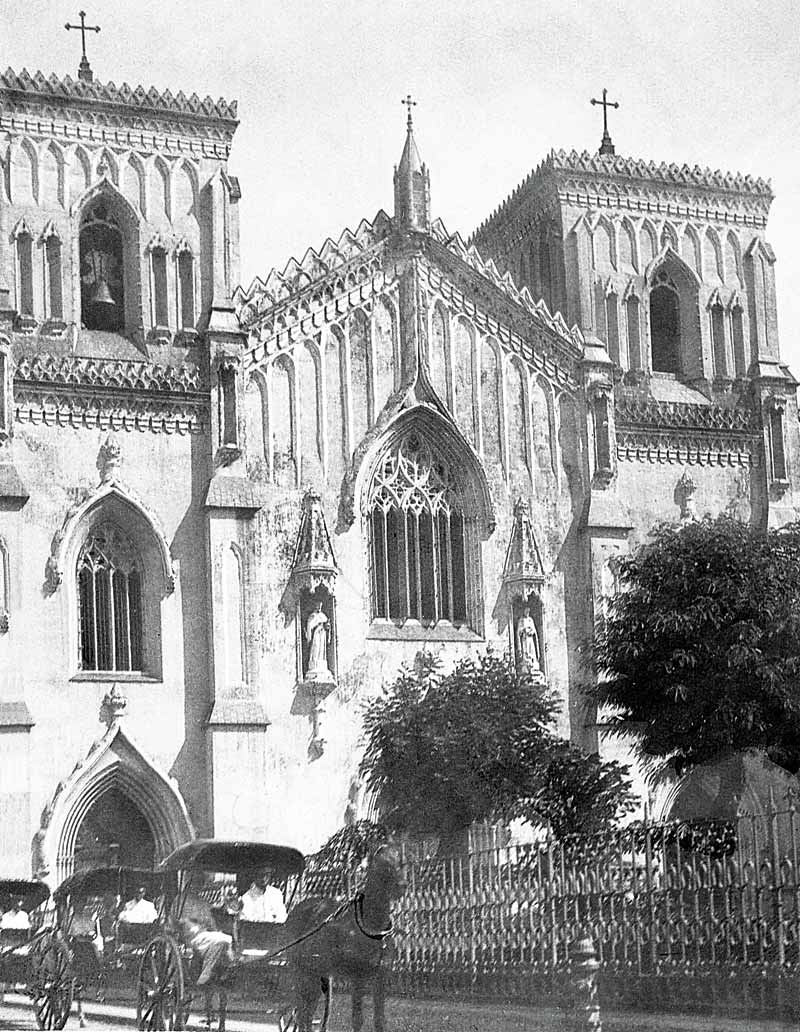

His more impressive works, however, were done as a private practitioner: mansions for his wealthy Rojas relatives, commercial buildings in Escolta, and churches, including the famed Santo Domingo and San Ignacio churches in Intramuros.

The book also tells the little known story behind San Ignacio Church, whose metal framework was designed and supplied by French engineer Gustave Eiffel (who would later design and build the Eiffel Tower in Paris, in 1889). Eiffel’s company was represented in Manila by Jacobo Zobel, a nephew-in law of Rojas, and whose palatial ancestral home in Intramuros was one of Rojas’ first building projects. Research thus confirms the Eiffel connection in Philippine church architecture, but not with San Sebastian Basilica, as some believe.

Tomas Fernandez Arguelles (1860-1950)

Arguelles’ career spanned the Spanish, American and post-war periods. He received academic training in surveying at San Juan de Letran, and in architecture at the Escuela de Artes y Oficios (School of Arts and Trade). Tomas is the father of Carlos Arguelles, himself a pillar of Philippine modern architecture.

Arguelles started work as an inspector for the Street Car and Manila Railroad companies from 1884 to 1896, agrimensor (land surveyor and assessor) for the Recollects in 1897, and maestro de obras in 1898 to 1924. He served in the Revolutionary Army against Spain, with the rank of captain; the advisory council of the City of Manila; was one of the founders of the Camara de Comercia Filipina (Philippine Chamber of Commerce); and founding member of the Philippine Architects Society (the precursor to the PIA).

In the book, his son and granddaughter write: “Arguelles was automatically licensed to practice architecture under the Engineers and Architects Law of 1921. He is holder of Registration No. 9, granted to him in 1922 when he was already in his senior years. The license was merely a formality as Arguelles had been actively practicing in this profession decades earlier.”

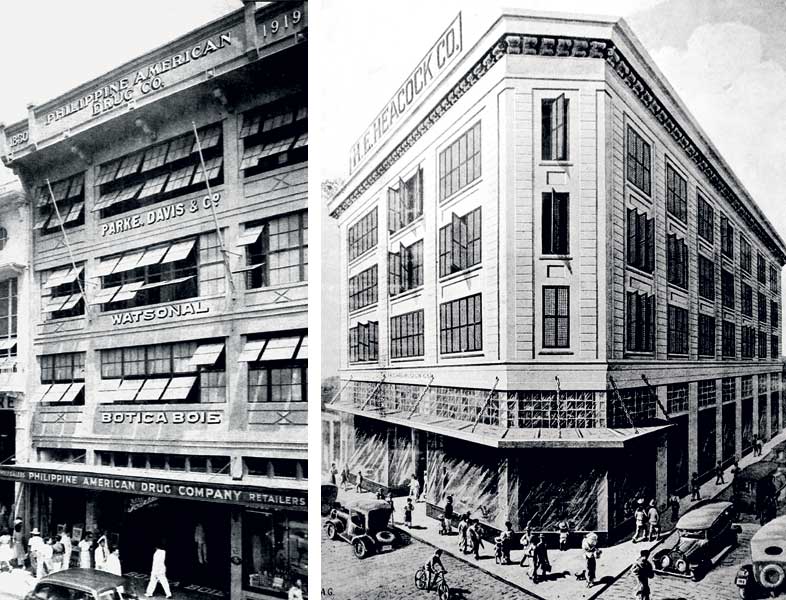

Among the structures he designed before he received his license were the Municipio de Manila or Manila City Hall when it moved out of Intramuros; the train stations of San Fernando, Pampanga; San Miguel, Tarlac; and Hondagua, Bicol; President Manuel L. Quezon’s mansion in Pasay; and the Botica Boie and Burke buildings on Calle Escolta, to name but a few.

Arcadio De Guzman Arellano (1872-1920)

Arellano’s father, Luis, was a maestro de obras and Arcadio followed in his father’s footsteps, pursuing the building trade after his business studies at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila in Intramuros, and taking further studies at the Escuela de Artes y Oficios (est. 1890), where he graduated in 1895. Arellano served in the engineering corps of the Revolutionary Army with the rank of captain. The American colonial government retained him to supervise the assessments in Intramuros, and eventually the whole of Manila, after which Arellano took part in preparing the building code for the city.

Later, Arellano would work as Governor W. H. Taft’s private consulting architect. Three key groups of projects emerge from the wealth of Arellano projects revealed in the book. One, Arellano seemed to have inherited the “post” of the Manila elite’s architect of choice after the death of Felix Rojas. Arellano built the palatial homes in Quiapo of the Hidalgos, the Paternos, the Aranetas and the Tuasons, as well as the Ongpins of Binondo. The latter’s legendary El 82 Bazaar was also a design of Arellano.

A true nationalist, Arellano also had numerous projects related to the revolutionary movement. He particularly took pride in the Mausoleum of the Veterans of the Revolution that can still be found at the Manila North Cemetery. A third group of works, the later works, were decidedly more modern in aesthetic, reflecting the collaborative partnership of Arellano with his younger and US-schooled brother, Juan. Their joint projects, such as the Casino Español and Gota de Leche, defined the character of the city of Manila.

Andres Luna de San Pedro (1887-1952)

“Andres Luna would probably be the biggest revelation to most students and enthusiasts of Philippine architecture. Very few know him, or know him only as the son of the great painter Juan Luna. Those who know of Andres only identify him with the Regina, the Perez–Samanillo, the Natividad and the Crystal Arcade Buildings in Escolta. His resume is much thicker and more impressive than that,” Rico enthuses.

Luna was born in Paris, and grew up in the company of the ilustrado and inteligentia community of Filipinos in Europe, including National Hero Jose Rizal. In 1894, he returned to the country, took private art lessons under Manila’s best, but eventually went for architecture studies at the International Correspondents School in Manila. He went back to Paris to study architecture at the Ecole de Beaux Arts, and earned valuable experience by working under known Parisian architects Gilardi, Paulin, and Bertoner.

Upon his return to Manila, he was appointed City Architect, a position he held from 1920 to 1924. Like Rojas and Arcadio Arellano, Andres Luna became high society’s favored architect, sought after both for his pedigree and his unique style of Filipino-French architecture. The ritzy pre-war Dewey Boulevard (now Roxas Boulevard) was once lined by bayside palatial residences, a significant number of which were designed by Andres.

Fernando Hizon Ocampo (1897-1984)

Ocampo finished his Bachelor of Arts at the Ateneo de Manila University, obtained a diploma in Civil Engineering at the University of Santo Tomas, studied architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, and took further studies in architecture in Rome and Fontainebleau.

Ocampo wore many hats. He had a brief stint at the Bureau of Public Works in the early 1920s as Assistant Architect. As an educator, he was affiliated with three schools—the Mapúa Institute of Technology, the University of Santo Tomas, and the short-lived Philippine College of Design. He sat on the Board of Examiners for Architects, and was a founding member of the Philippine Architects Society in 1933, and served as its president in 1945 under the current name, Philippine Institute of Architects.

Although many of Ocampo’s architectural projects are found in Manila, among them the Paterno Building (later the Far Eastern Air Transport, Inc., or FEATI), the North Syquia and Admiral Apartments in Malate, as well as the renovation of the Manila Cathedral, many of Ocampo’s outstanding projects dot and enrich the architecture in the provinces, from Pampanga to Baguio to Iloilo.

Juan Felipe de Jesus Nakpil (1899-1986)

Nakpil was the first Filipino architect to receive the National Artist Award for Architecture in 1972. His father was Filipino nationalist and musician Julian Nakpil, while his mother, Gregoria de Jesus (the widow of Andres Bonifacio), was one of the heroines of the Philippine Revolution.

Nakpil studied engineering, which he started at the University of the Philippines and finished at the University of Kansas. For advanced studies, he went to Fontainebleau, and earned an MA in architecture from Harvard University. Nakpil began his practice as a junior partner of Andres Luna in 1926.

Four years later, he ventured on his own, and in 1953, went into partnership with his sons Ariston, Elogiol, and Francisco. While Nakpil’s design was at the forefront of Modernism in Philippine architecture (some even considered him “too modern”), his descendants, Arch. Francisco Nakpil and Rebecca Nakpil Tañada, emphasize in the book that he vigorously promoted architecture that was “attuned to the climactic, seismological, and environmental conditions in the country.” This value is seen in his promotion and preservation efforts of native building materials, as well as the modern adaptation of indigenous house models, especially the bahay kubo roof.

Nakpil likewise had a fulfilling and long career in the academe. At one point, the book says, “The deans of six architecture schools in Manila were all his former students.” ![]()

READ MORE: Forging Modernism: The early years of Leandro Locsin