Attempting to define Jorge Yulo by what he was not proved equally elusive. Not a post-modernist. Likely not a deconstructionist nor a formalist either, despite his playful manipulation of striking forms. What else not? “Oh, I’m evasive even to myself,” he admitted with a grin. It was time to throw the boxes out. After three […]

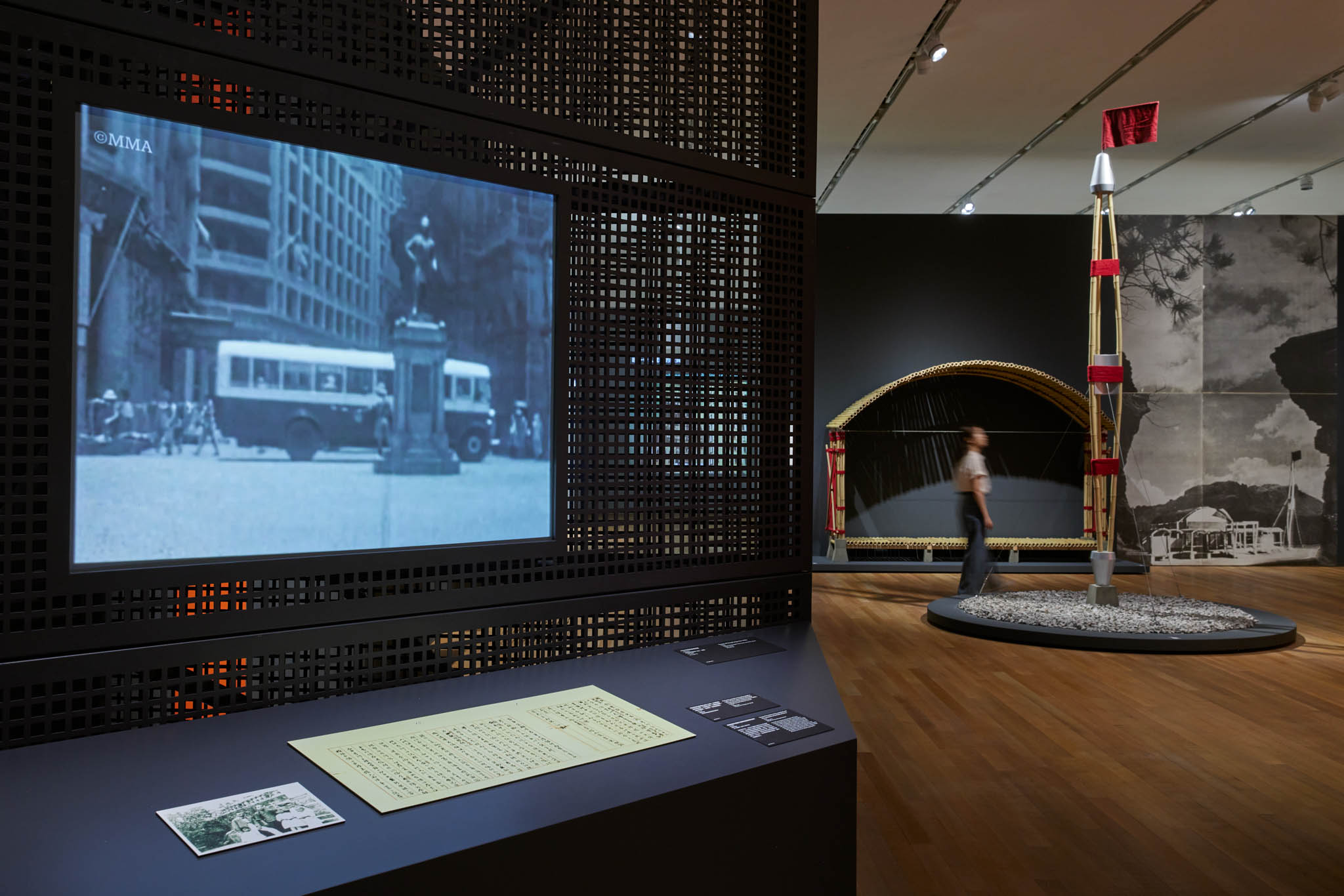

Cross-Cultural Expressions: I. M. Pei Retrospective Now on Display at M+

M+ typically creates exhibitions based on their collection, but the I. M. Pei Retrospective is an exception. Although the museum only had three items from the architect, the city in which it stands and where he once lived resonates with his global influence.

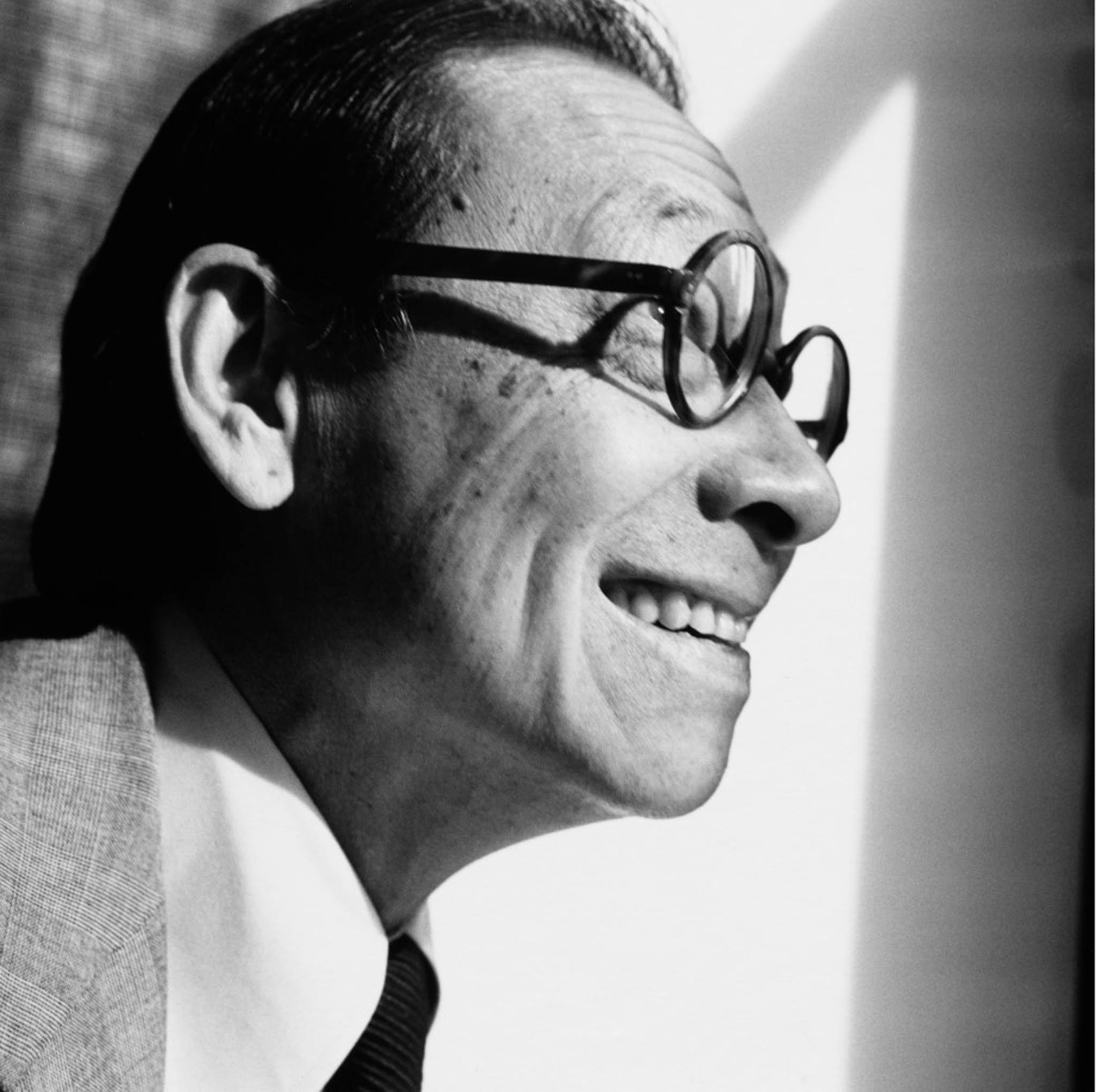

Portrait of I. M. Pei, 1976 | Photo by Irving Penn, Vogue © Condé Nast

Born out of a decade-long research process, helmed by Shirley Surya and Aric Chen, “I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture” is the first major retrospective focused on one of the most influential architects of the 20th and 21st centuries.

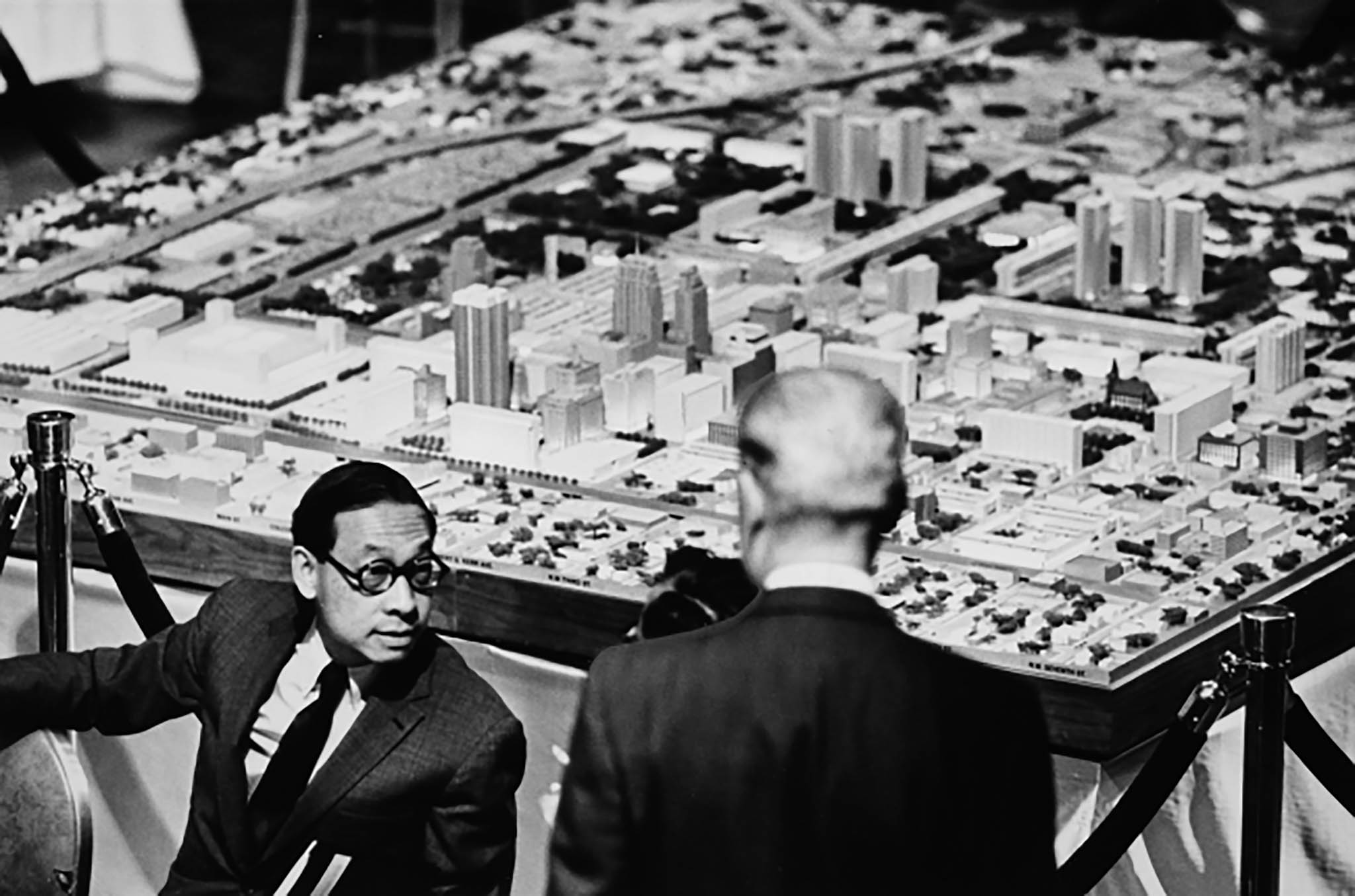

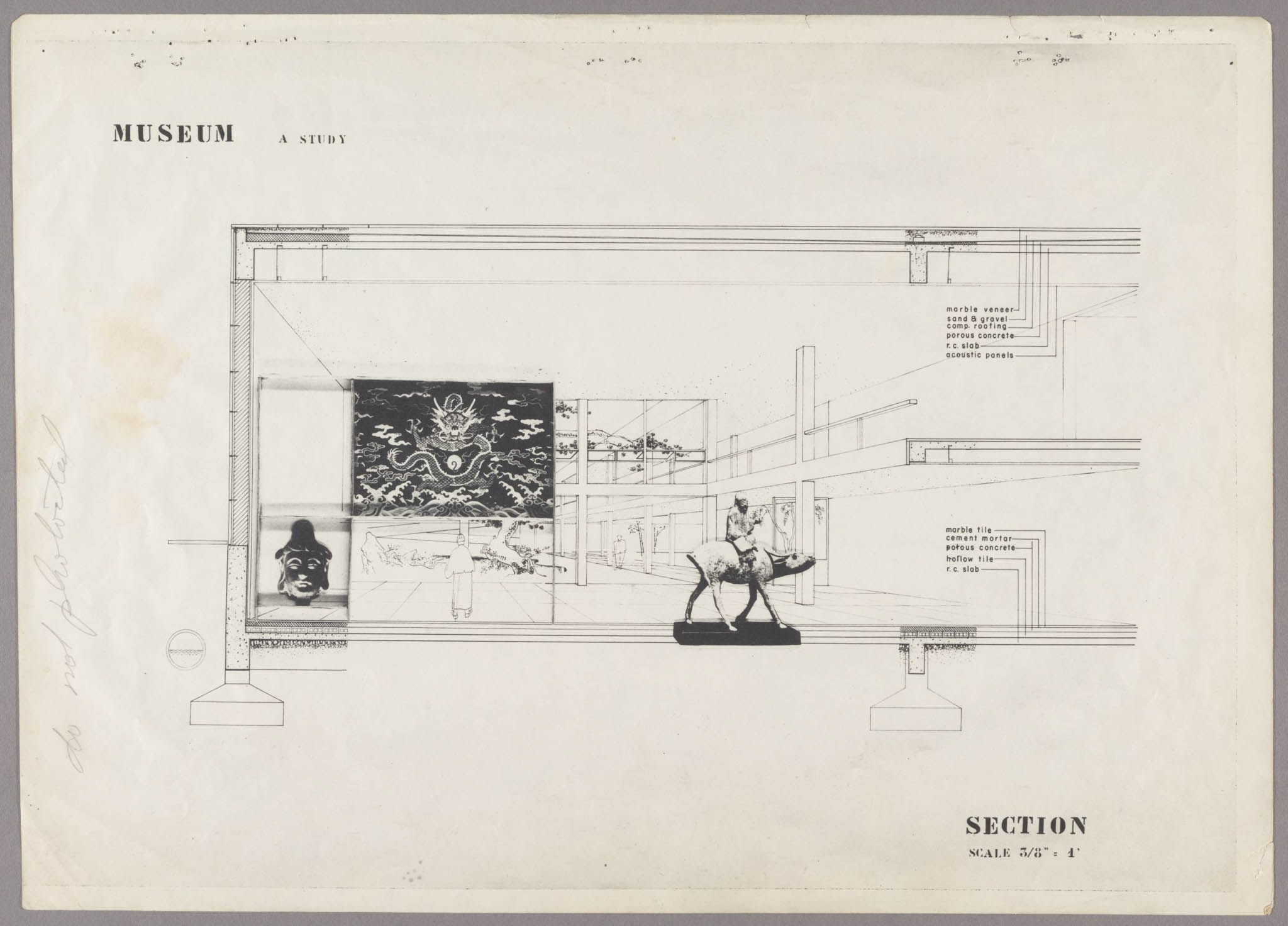

The exhibition, arranged thematically across six thematic rooms with some buildings recurring in different chapters, highlights I. M. Pei’s process and consistency. It dissects each project to focus on strategy and its relationship to the oeuvre, rather than offering in-depth ratings or walkthroughs. The work of associated professionals animates the exhibit—tempera renders by Robert Schwartz, ink needlepoints by Helmut Jacoby, monochrome snaps by Ezra Stoller, and drafts by Pei Cob Freed colleagues—highlighting the ecosystem that sustained the architecture.

Alongside the museums and institutional buildings, this exhibit illuminates the earlier years of his career, including his lesser-known work in affordable housing, mixed-use complexes (yes, even a suburban mall), and urban regeneration.

A copy of his typewritten MIT thesis is also on display, alongside bamboo models re-created by Hong Kong architecture students. It includes works from his time at Harvard GSD—including drawings he collaborated on with his wife Eileen, who was studying landscape architecture at the time.

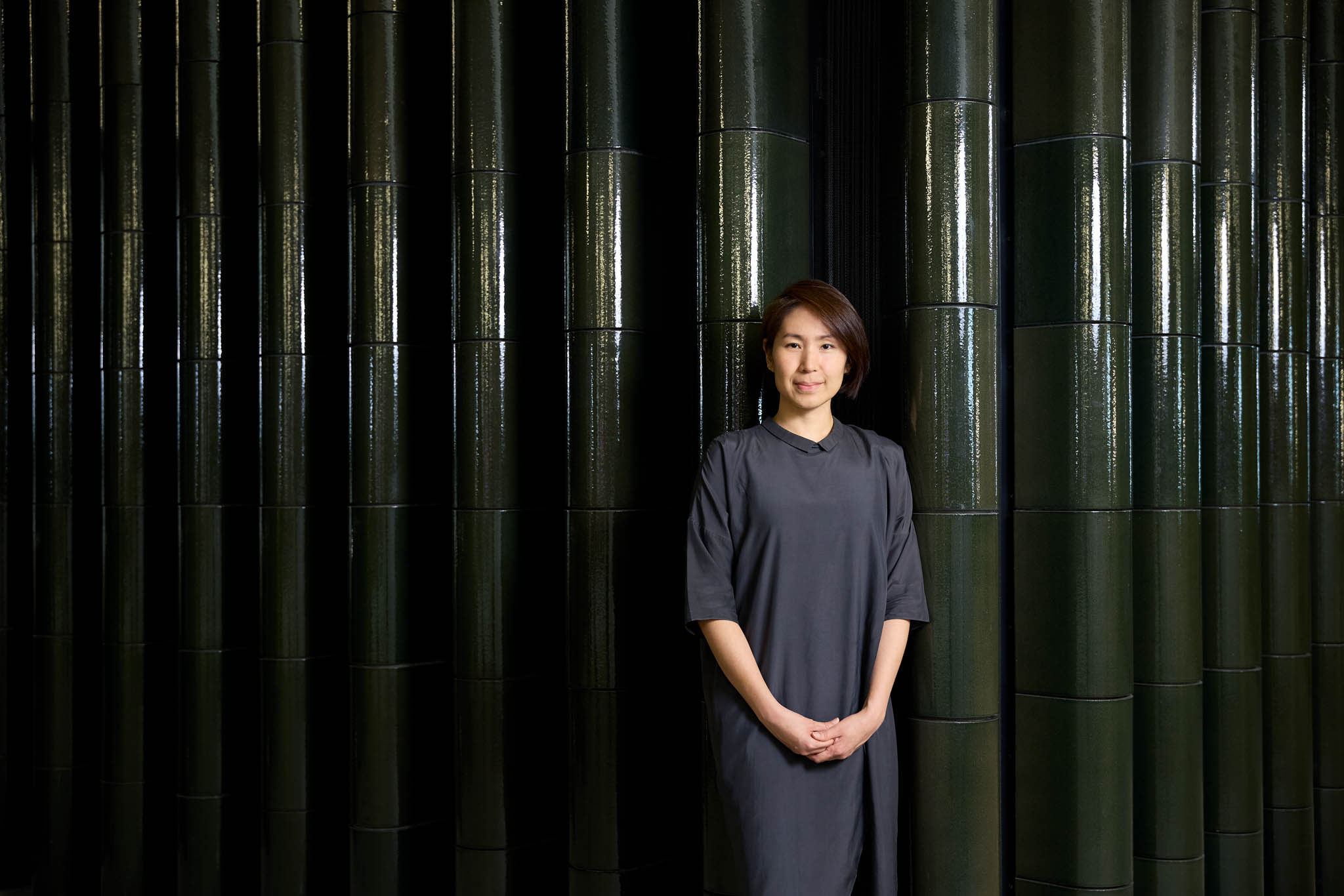

I sat down for an interview with one of the exhibit’s curators, Shirley Surya, in a museum seminar hall with floor-to-ceiling windows facing the Victoria Harbour. Across us, the Bank of China Tower, punctuating the Hong Kong skyline, stood as witness to our conversation and as a testament to I. M. Pei’s enduring architecture practice.

Where or who were the key sources of material?

We approached the Pei family in 2014 with the intention of acquiring items for our permanent collection, but we found out Mr. Pei donated his personal materials to the United States Library of Congress. My former supervisor and colleague, Aric Chen, the co-curator of the exhibition, investigated what else were available and what permissions were needed.

In 2016, we found out that Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, which succeeded the architectural firm Pei founded, had the materials. Because of COVID, we only got to see the materials twice in 2019. The rest of the time, we were relying on our researcher Janet Strong to dig through it and photograph them. It was a very arduous process.

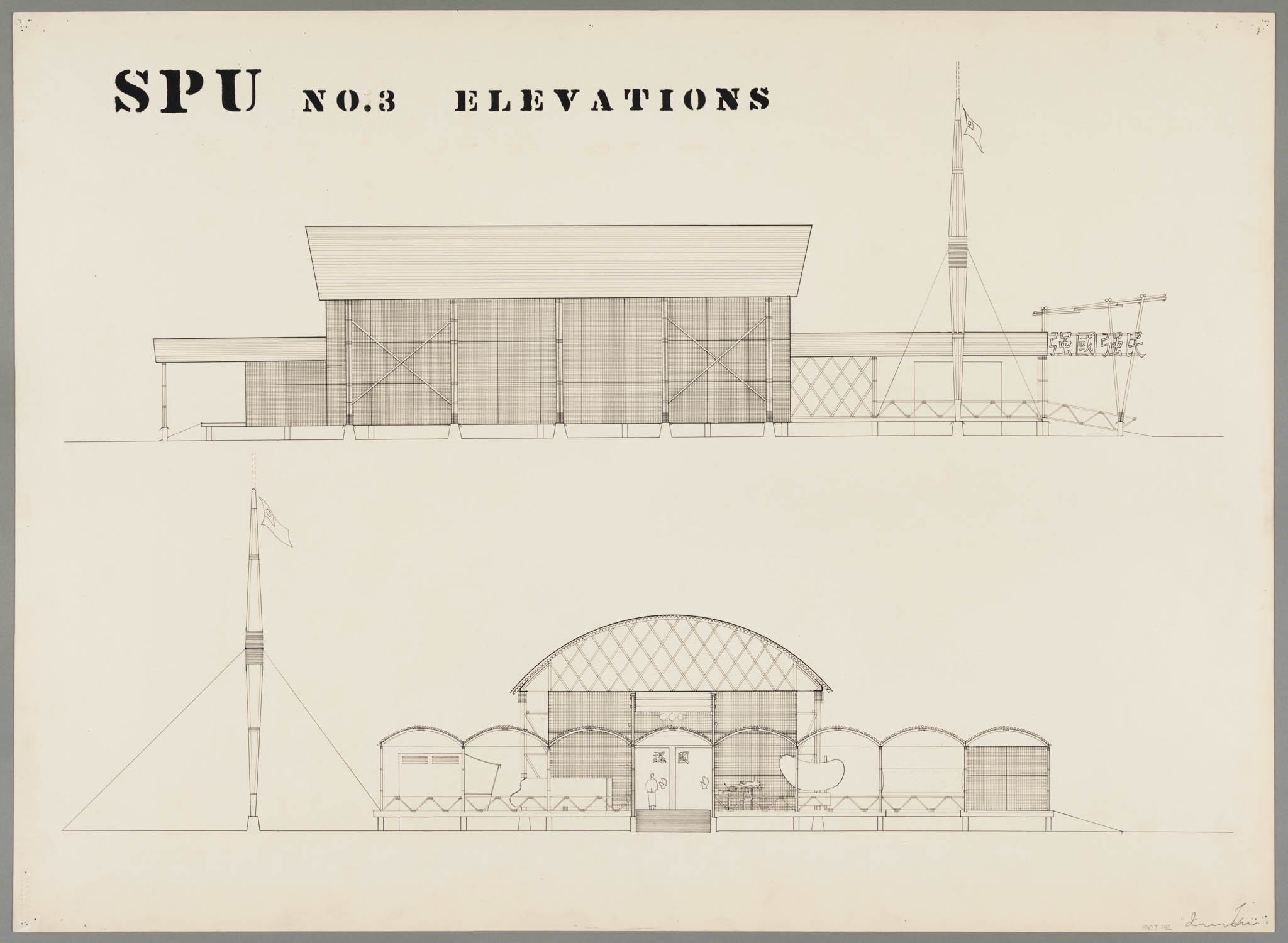

The biggest challenge was to communicate the buildings well to the public by showing models and different materials in the exhibition. And this exhibition is not meant for architects, right? It’s also meant for those who do not know who Mr. Pei is. So, we had to make the models. There were some model drawings given to us by the clients. Then, there were projects with no drawings, meaning nothing else apart from their very basic elevation plan; no details.

So, the architecture schools at HKU and CUHK were my first thoughts for the models because it would require the students and the tutors to reimagine Mr. Pei’s drawings into 3D. Then we could pass it on to the model makers to reproduce. That process required about one year of orchestration before the exhibition opened.

We wanted the models to highlight Mr. Pei’s use of materials like bamboo. The Luce Memorial Chapel, that one is hand-welded stainless steel. It’s not just computerized and pressed into a mould. Models were created by hand. We are very grateful for our collaborators.

I’m sure that the students were excited to interpret his work.

Some of them were, but I also want to share that Mr. Pei is not a figure that is very sought after by the young generation.

It’s just that the industry has long revered very conceptual architects, right? Conceptual here means they have very good ideas, but whether the buildings serve 100,000 people or only 10 people doesn’t really matter to them. They just want the idea. Mr. Pei is an architect beyond the ideas. Also, because he built only until the 2000s, the students don’t talk about his projects much in school.

Some of the students were skeptical, some were curious, some of them even criticised how come his drawings were not sufficient. For us, it’s alright. We were not seeking for respect like a master or a complete adulation of Mr. Pei.

It’s just more about looking at his design. What does it mean? What was he trying to do in that time and place? So, I think it became a meaningful exercise with the students.

No architect is perfect. We just know that he’s important. The word ‘importance’ is something that the exhibition and the publication of this project tries to reevaluate. Because what the world thinks is important is maybe theoretical architect, conceptual architect, gestural, formal architect. Yes, I can understand that’s important, but that’s not the only criteria. So, we hope how we present Mr. Pei’s work can show those other aspects.

This is not just one man’s work on display. Here you see the network of minds and talent he brought together—architects, artists, the illustrators, real estate professionals, government, institutions, and more.

Of course, Mr Pei’s firm is a corporate practice. It’s not a firm that designs private residential homes. So, the very complex projects that he undertook required a big team. Sandi Pei, his son, also told me that his dad works very collaboratively and likes to draw out the best from his team.

In gathering the materials, what patterns or key principles did you notice in his work?

There is no stylistic consistency. But is that important? So, not every building is going look distinctly his, unlike, say, Frank Ghery. So, his portfolio is quite diverse looking, but there are consistent principles.

The ‘people’s space’ is very important for him. Something as simple as the park or the central gathering space of the museum, what does it say? It says the building is not meant to be a complete function of economics.

He could have made Kips Bay Plaza have three building blocks. Instead, he made a park that is half the size of the entire plot. What does it do? It brings the value of beauty across time, and Kips Bay, which was meant to be low-cost housing, became a condominium and coveted address in the 1980s.

It also happened in the mall that he designed, Roosevelt Field. It’s not just one big shoe box, it’s small blocks with streets, lanes, and a gathering space almost like Clark Quay in Singapore in the 1950s. The central canopy is meant to shelter an ice-skating rink.

Same goes for the Louvre. In the models that Mr. Pei built of the 600-year evolution of the Louvre, you can see the development is inorganic, very asymmetrical, snaking almost. Then, you realise that having that little pyramid in the middle creates an appearance of symmetry not only within the complex, but in relation to the entire city up to the Arc de Triomphe.

He considered the micro and the macro scale, from the crafted building up to the city—not all architects can deal with both.

Whether he was in China or outside, he was always trying to reengage tradition and history. People might think: of course, all architects must think about it. The defining feature is how Mr. Pei had a visceral dialogue with the place of his buildings.

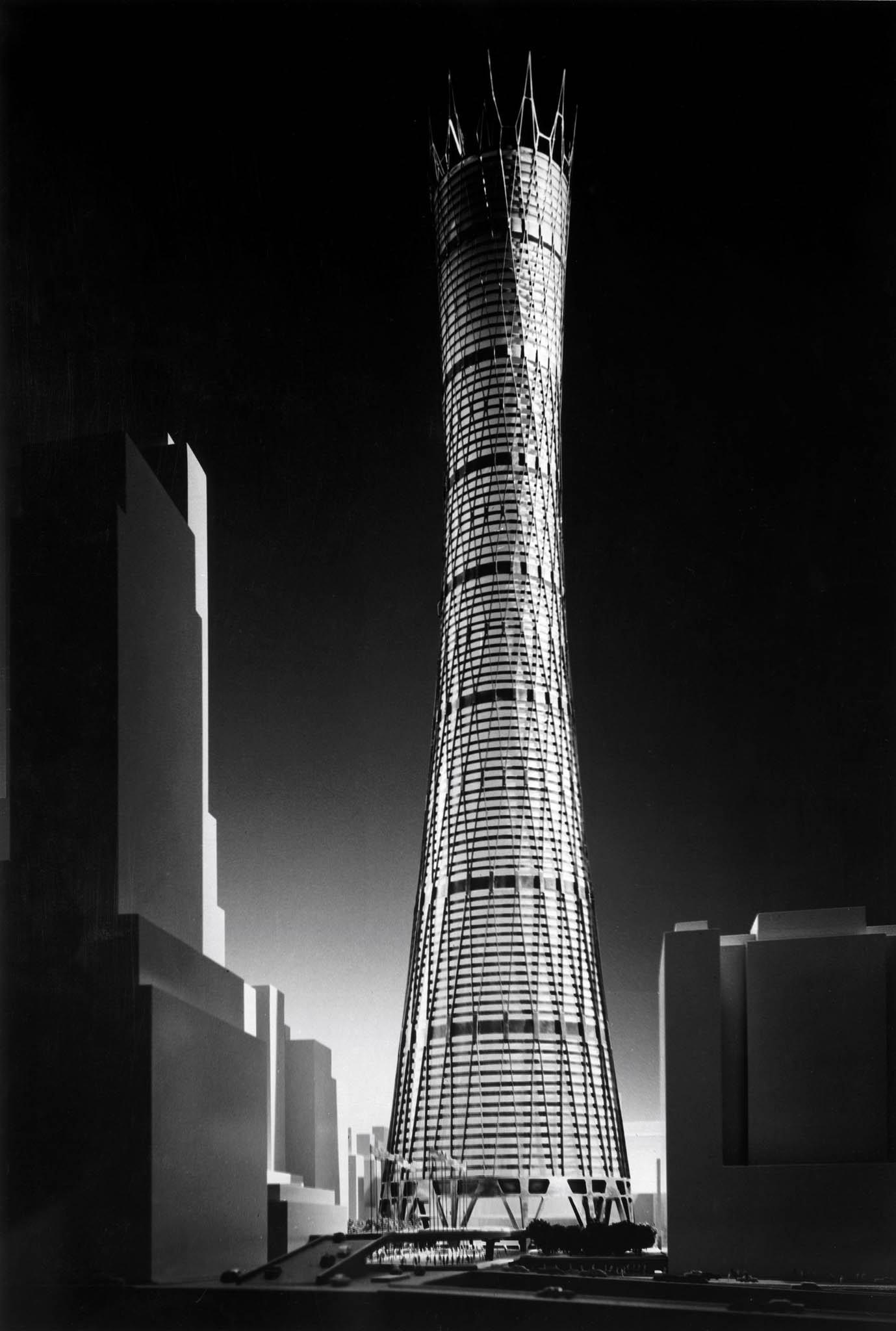

The Museum of Islamic Art was a pioneering project for Qatar and its ambition to be a global hub for culture. Now, there are many other museums trying to be in conversation with the Islamic world. Mr. Pei really wanted to root his design in a particular building, which is why Ibn Tulun is a key reference point.

The geometric progression of the square, the octagon, and the circle also informed the progression of the MIA. There is a very precise connection with the historically present building because it has, for him, stood the test of time in a very real way as it is still being used.

The material is earthy, almost sand-like, very much part of the land. He chose something that is very simple because the exterior is not ornamented and it works for Doha, because Doha is not an Istanbul. It’s a very young city. But inside it’s very intricate, undoubtedly Islamic, with the dome and all of that.

I compare this to a project seemingly unrelated to ethnicity: the National Centre for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Denver, one of our favorite buildings.

It’s in the middle of Colorado. But even in that kind of setting, Mr. Pei still sought for a route through the Puebloans cliff dwellings because they were an example of how shelter is built in a vast arid land by the Rockies. The concrete is mixed with the stone aggregate that’s quarried nearby. So it appears fixed to the rock of the mountains, but also set apart because of the towers.

I. M. Pei has momentous work and, of course, the exhibition highlights this. Most people recognize The Louvre or Bank of China Tower. But in every architect’s portfolio, there are lesser-known gems. What do you think those gems are?

The biggest little gems, for me, are those that are from his Webb and Knapp days. The Bedford-Stuyvesant Regeneration Project required us to hunt for material extensively, using any search tool we could find.

We knew Bedford through the former chief planner of Singapore, Liu Thai Ker, who had worked with Mr. Pei for about five years in the 1960s. It’s one of the largest Black neighborhoods in the country. During the civil rights movement, Robert Kennedy, who knew Mr. Pei through the JFK Commission, asked him to undertake his very first pro bono project, which he usually did not do. This was not because he just wanted money, but he’s an example of an architect who wants to maintain his firm.

For that project, we have only two images: a master plan of the green grounds and a photograph, plus an article. I could not exclude this because it was the very first example of community design. It was also done with Franklin Thomas, the first Black head of the Ford Foundation, a highly respected figure in the community.

We found out from the text and his interview that they designed together with the people and in consultation with the people. All the construction was done by people from there because it was important for them to have a sense of ownership. So, it may not be true that Mr. Pei does this for every single project. This is a very rare one, but he was capable of engaging in that process.

Society Hill in Philadelphia was built at the same time as Kips Bay. It was low-cost housing, again part of urban renewal, but the difference is the area is a very historical site. There were red brick houses from the 1800s—you will have to relate to these mansions, but you’re also supposed to build high.

He did this by orienting the towers in relation to the neighborhood and constructing surrounding low-rise housing using the same materials as the historical buildings. Additionally, the windows of the low-rise structures matched the proportions of those in the high-rise buildings.

Behind the scenes, a lot of negotiation and consensus building must have happened. We see that play out in the video of I. M. Pei and Mr. Moore to find a placement for the sculpture at the National Gallery. I really appreciated that. Were there other facets of his character that you discovered as the exhibition came together?

The word ‘consensus’ means as though a project will not move ahead unless everybody says ‘yes’. If there was resistance, Mr. Pei is also someone who pushes. Of course, he seeks to align and to be in conversation with the client to convince them. However, there are instances where he insists, and the client does not respond, yet he proceeds regardless.

The question of ‘how Chinese he is’ recurs, with some people accusing him of being nostalgic. I have discovered that his interest in exploring Chinese identity is not rooted in nostalgia, but stems from the rise of nationalism in 1930s China. Around that time, he had gone to MIT.

Not only that, but there was also one building in Shanghai that made him want to be an architect when he was a teenager called Park Hotel done by László Hudec. It still stands. That hotel also led him to question what it means to be Chinese developing the country, contributing to the country. It was the first high-rise building, not in The Bund but in midtown Shanghai, done by Chinese bankers and not by foreign masters.

So, at Harvard, he expressed the need to explore both a national and regional identity, feeling that the international style or modern architecture of Gropius was insufficient.

So, what would it be? There are many ways of Chinese-ness, right? Red, big roof, bamboo? He chose space in the form of the Suzhou Garden. It’s about an unfolding of spaces, indirect viewing, framing, the secretiveness and succession of space, the multidirectional kind of experience which he first encountered as a kid playing in the private garden of Shi Zi Lin.

The Chinese garden is dynamic, not applied in a static way.

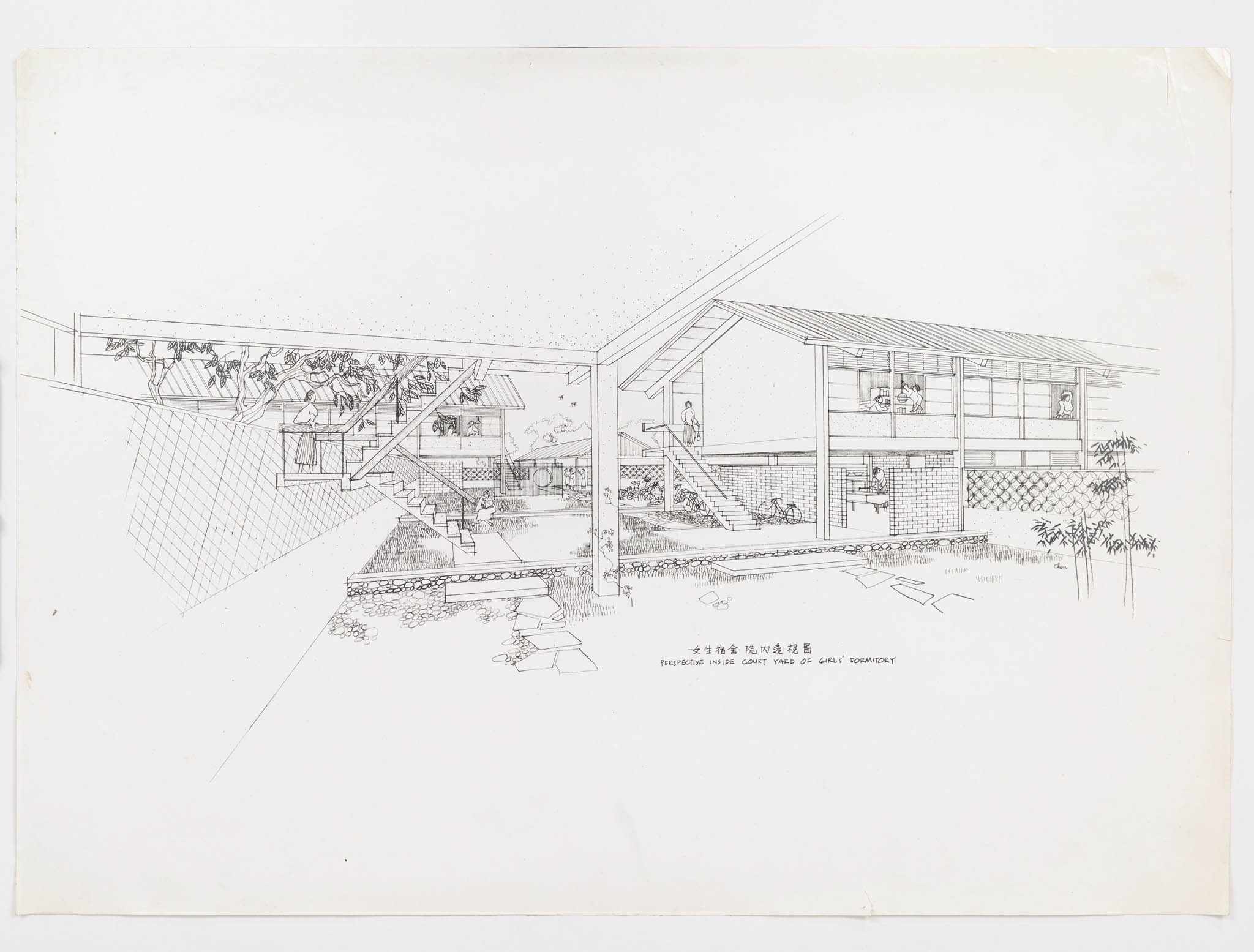

The Expo ‘70 Pavilion in Taiwan doesn’t resemble a Chinese garden, but its path is like a vertical garden, designed for you to wander around. Despite being confined to two triangles with three bridges, you don’t know where you’re going. In Tunghai University, there is the asymmetrical clustering of academic buildings around the courtyard.

Perspective inside courtyard of Women’s Dormitory, Tunghai University (1954–1963), Taichung, ca. 1955, reprographic print. Photo: M+, Hong Kong, digitised with permission. © Pei Cobb Freed & Partners.

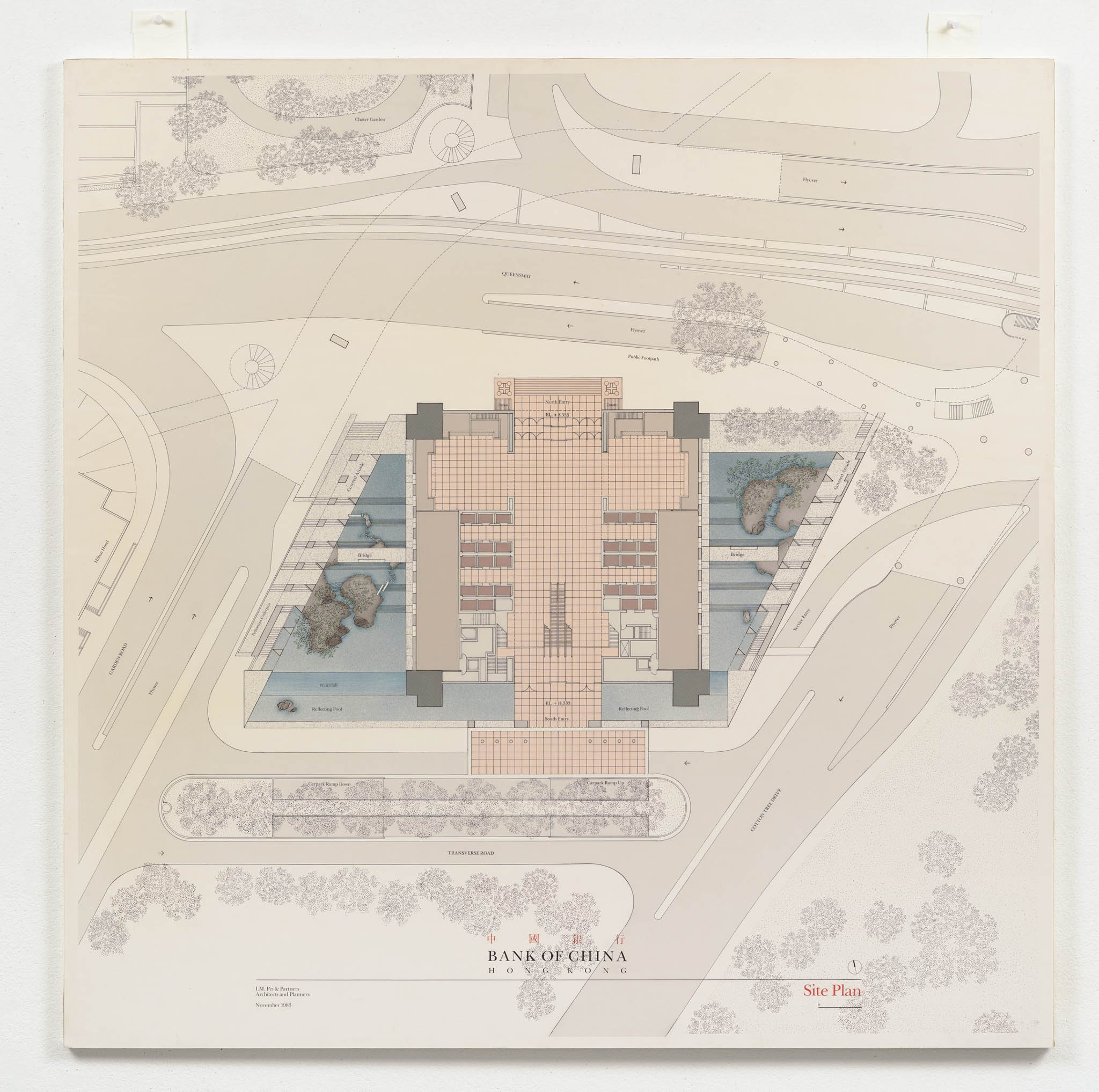

The garden also appears at the Bank of China. How can the tower be framed on the slope in a dignified manner? It needed an earth element. The garden here is designed to be like a fountain, rather than a typical large garden, and also serves as a sound buffer. The cascading water is part of this design, acting like a necklace for the entrance at the back of the Bank of China. The pool begins in front of the entrance and flows downward.

Suzhou Museum is a completely different case as it sits next to a UNESCO garden. The aerial drone shot we had shows the museum and the administrator’s garden, similar in color and proportion. However, once you’re at ground level, they appear quite different. He has a way of engaging in dialogue with the surroundings while setting the project apart for contemporary use.

He did not shy away from the commercial aspect of the industry. However, with the rise of computerized design, the pace of commercial projects is so different today. The process of design has always been iterative, with architects always returning to their drawing boards. But today, it is iterative and rapid, and, in some instances, automated. What now is the role of an architect or designer in our time?

I want to link that back to the show. People consider him old school, or laozi in Chinese, a very classical architect. So, we purposely ended the show with the last clip, anticipating that some architects would be very critical of it. Although no one has said this to me yet, I can imagine comments like: ‘What’s this man like? So fundamental, even a child could articulate that. Can he say anything more sophisticated?’

But those basic thoughts are often overlooked today. Are you being thoughtful? Are you dedicating time to the design process to create thoughtful designs? Are you being responsible?

I’m not saying the blame lies solely with the architects; the entire industry ecology also has very misplaced priorities. This is why I had to put the video of William Zeckendorf’s speech in Room 2. He was a real estate developer.

I remember that. He had very strong points. “Beauty is the only thing of…

..imperishable value. Yes. And it’s addressed to the public. He was not talking about beauty just for your own private gallery.

I hope the exhibition will address those fundamental values that need to be reappraised. What is your fundamental ethos in architecture or development? Can you push it? Can you negotiate or do you simply accept the brief? Can you affect more than just the building?

Mr. Pei could have simply designed the BOC tower and left it at that. However, he didn’t accept the site as it was. Instead, he pushed for negotiations with the Lands Department. Perhaps because he was Mr. Pei, he had the influence to engage with the government. I’ve encountered young architects who aspire to do the same. It’s not easy, and they may fail, but they are trying.

The brief isn’t something fixed; it needs to be renewed and questioned in terms of public good while still being economical. I see him as an example of this. The value of being a neighborly architect isn’t superficial.

I also put the responsibility back on the media and the user. This show highlights not only how architecture is produced but also how it’s consumed—what the media says about it and what people think of it, whether they like it or not. I believe we all have a role in shaping the kind of buildings and cities we want to create.

It’s important to have a perspective or a value system. Of course, we can also say that he was building at a time when resources were abundant. Today, we face environmental concerns, and building with concrete is no longer considered as sustainable as it once was. However, this doesn’t mean we can do everything with wood either, due to issues like fire safety.

It is more difficult now, but I hope this inspires people to question what is possible in our current context. I hope that the work of so-called classical architects will raise these important questions.

Image courtesy of M+, Hong Kong.

![[From left] Sarah Crescimbeni, the sales manager for Poltrona Frau, Florence Ko, owner of Furnitalia Philippines, her husband, William Ko, and Davide Geglio, the Italian Ambassador to the Philippines.](https://bluprint-onemega.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Elle-Feature-Cover.webp)