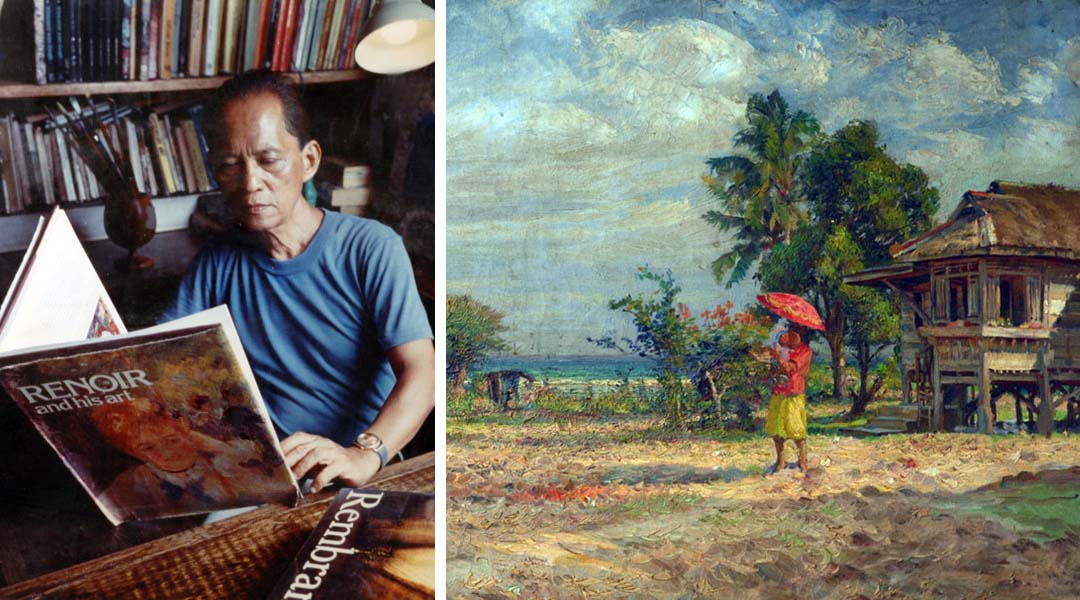

The Enlightened Maestro: Martino Abellana, the Amorsolo of the South

A patient, understanding teacher famed for his savage wit and impatience with mediocrity, the late Martino Abellana (1914-1987) exemplified for many generations of artists in the Visayas, the ideal maestro artist. Called by his admirers as “the Amorsolo of the South,” Abellana came from a highly talented family of artists from the prosperous heritage town of Carcar, an hour’s drive south of Cebu City. His grandfather, Gonzalo, migrated to this seaside town facing southern Bohol in the 1890s from Cebu City and was known as an accomplished designer of embroidered church vestments. Martino Abellana’s father, Teofilo, was the town’s elementary school principal, an accomplished pianist, and is immortalized for his sculptural designs on Carcar’s glorietta pavilion dating from 1927 that still stands today along the highway near the public market. Finally, his brother Ramon, a dentist, was also a sculptor who made the statue of Lapu-Lapu found at the Cebu City Capitol.

This predisposition towards the visual arts would reward Martino Abellana’s considerable talent. The only one in his family whom his father permitted to take Fine Arts, Abellana studied at the UP School of Fine Arts from 1933-1936, where Cesar Legaspi and Carlos “Botong” Francisco were fellow students. His companion in Manila was Manuel Rodriguez, Sr., who would find his fame as the country’s father of printmaking decades later. Falling under the sway of the gentle Fernando Amorsolo as a student, Abellana would accompany him in extended sketching tours in Manila’s suburbs during the Thirties, imbibing the sensibility of plein aire painting that Amorsolo’s circle, which included Toribio Herrera and Dominador Castañeda, exemplified. Another influence was the academician Vicente Rivera y Mir, whom Abellana learned a love of classical art, and who advised him to visit Europe to see great western art, a task that Abellana undertook only near the end of his life.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Napoleon Abueva’s Gothic “chapel” workshop

Forced by his father to go back to Cebu just before the outbreak of World War II, Martino Abellana would become the island’s most celebrated artist and most well-known art teacher in the post-War era. He devoted forty years of his life teaching in the various fine arts schools in the city while always commuting back to his beloved Carcar, where he found peace as a family man and an outdoor painter. However, it was Abellana’s facility with portraiture that found him eminent admirers among the elites of both Carcar and Cebu City. As the only real income generator in the Cebu art scene during this time, portraiture became for Abellana a necessary task which he applied with sensitivity and almost scientific discipline. Relying on photographs, Abellana would translate his subjects with an almost sensuous delight in color and gesture, enfleshing them with an unforgettable paean that speaks of the subject’s arrival on the social scene with grace and dignity. This mastery of the human figure found its one national hallmark when Abellana won the first prize for Conservative Painting at the 1953 AAP Art Competition for Job Was Also Man. His winning piece is a sensitive and searing portrayal of an old man sitting among ruins, palm up in a pathetic gesture of seeking charity from passers-by. Another painting of the period, a family group huddled together in prayer, also spoke of the timeless practices found in the countryside, and which were part of Martino Abellana’s world of family, faith, and the need to persevere against the vicissitudes of life.

Among the most poignant of Abellana’s portraits, however, are those of his own family, like his daughters, whom he captured with sensitivity and love that only a proud father could convey. Depicting his daughter Ellen in complete Flower Power getup in a 1970 portrait, Abellana also acknowledges the modern transformations that have come and did not resist these changes. Instead, he attempted to understand them and put them into context, like his experiments on abstraction and expressionism that he did in the early-1960s to find out if he was adept in this newfangled movement.

READ MORE: The prolific life and house-studio of Abdulmari Imao

However, it is arguably Martino Abellana’s landscapes that would truly be ranked with the best works of art ever produced by a Filipino painter during the 20th Century. Although he followed Amorsolo’s and Rivera y Mir’s precepts regarding academic painting, Abellana was also open-minded enough to incorporate more modern techniques like impressionistic divisions of shades using primary and secondary colors, rather than academic browns and blacks, and a more vigorous brushwork using alla prima techniques, like Post-Impressionist artists Paul Cezanne or Vincent van Gogh. Because he was under no social obligation to depict his landscapes in a photo-realist manner, which was de rigeur in the realm of portraiture, Abellana was free to experiment and innovate when it came to his outdoor scenes of Cebu. Abellana’s subjects for landscape, unlike the ricefields of Amorsolo or his Mabini followers, were the seascapes and mountain views of Carcar, as well as nearby scenic towns like Barili and Boljoon, with their intact colonial architecture, quaint provincial charm, and an almost isolated rurality far removed from the noise and roughness of the city.

A distinct impressionistic style characterizes Martino Abellana’s landscapes, in which the extravagant coloring of Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, and George Seurat was combined with the mystical earthiness of van Gogh’s and Cezanne’s outdoor scenes of Provence. This is distilled through the clarity of brilliant tropical sunlight that could only come from Abellana’s inculcation of Amorsolo’s landscapes. However, Abellana favors a clearer depiction of a bright morning or mid-afternoon sunlight, with its tendency towards brilliant blues and bleached whites, quite unlike Amorsolo’s sunset-tinged yellows and oranges. The clear quality of this light is as much a realization of the distinct Cebu rural atmosphere as it is an acknowledgment of Abellana’s brilliance as an observer of nature.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Artist Charlie Co keeps his passion for art alive in his art house

This liberative release that Martino Abellana found in landscape has also touched and inspired his fellow Cebuano artists, particularly his students, to imitate and celebrate with him the uniqueness of this landscape, setting in motion a habit among local artists who until now roam the seaside towns of the island during weekends, painting away scenery that may one day vanish under the inexorable push to modernize the island’s economy. More importantly, it was the possibility gained from Abellana’s portraits that these subsequent generations of artists have also emerged as accomplished portraitists. These artists, patiently nurtured by Abellana since their youth as their incontestable master-teacher, also found in Abellana a fatherly figure who would not hesitate to give them advice, such as working in Manila to raise the level of their art to heights of excellence that could only come from engaging with the centers of finance, culture, and power.

Two such artists benefitted the most from this advice: one was Sofronio Y. Mendoza, more known as SYM, a co-founder of the Dimasalang Group of Artists, who is now a celebrated Canada-based cubist. The other is the famed portraitist Romulo Galicano. It is through Galicano’s body of work that the mastery of Martino Abellana as a beloved teacher, who gave his students the freedom to express themselves via exacting standards of technical excellence, would be celebrated by a nation only now realizing what this enlightened maestro has done for the sake of national culture from an obscure but brilliantly lit Cebuano town.

This article was first published in BluPrint Volume 3 2009. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

READ MORE: Dissecting the stained glass windows at the Manila Cathedral

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Martino Abellana was a Cebuano painter known for portraits and landscapes. He was called the “Amorsolo of the South” for his mastery of light and color.

His famous works include Job Was Also Man, Carcar Seascape, Family Group Seated on a Piece of Earth, and portraits of his daughters.

He was known for impressionistic landscapes and portraits that blended Amorsolo’s light with modern brushwork and vibrant colors.

He was born in Carcar, Cebu, a heritage town whose scenery and culture inspired much of his art.

Abellana was influenced by Fernando Amorsolo, Vicente Rivera y Mir, and European masters like Cézanne and Van Gogh.