Sugarlandia Visita Iglesia: 5 Bacolod churches to visit this Holy Week

For one of the more prosperous provinces of the country, which produces more than half of the Philippines’ sugar crop and is famous for its mardi gras-like Masskara festival that is celebrated with lots of dancing, eating, and fanfare, one would expect more ebulliently lavish attention to be paid to its churches.

Bacolod churches (as well as those in surrounding cities) cannot compete with the majesty and historical significance of those in Ilocos, the effusive detail and adornment of those in Iloilo, and the gravitas of those in Batangas. Still, there are Roman Catholic houses of worship here that are worth visiting this coming Holy Week. Curiously, it is the smaller churches and out-of the way chapels that are more memorable, and perhaps more representative of the passionate Negrense people.

1 Church of the Angry Christ

In the Chapel of St. Joseph the Worker, located at the heart of the Victorias Milling Company (VMC) in Negros Occidental, a gigantic painting of Jesus Christ glares down at the nave. The imposing figure is part of a mural painted on the wall behind the altar, all rendered in psychedelic colors. Because of this, the church has come to be better known as the Church of the Angry Christ.

Despite the menacing expression and pose of Christ in the mural, the Chapel of St. Joseph the Worker was built to serve as the spiritual center of the VMC’s workers. The church was built after World War II, right after the province was recovering from the war. Three individuals were commissioned for the creation of the church: Czech architect Antonín Raymond for the structure, a Negrense named Alfonso Ossorio for the murals, and Belgian artist Ade Benthume for the mosaics.

READ MORE: Venice Biennale “Muhon” Exhibit starts regional tour in Bacolod

The talents of these three resulted in a mid-century modern church that makes use of tropical and earthquake-proof design. Even the icons and statues are localized with brown skins and Filipino features. This conglomeration of different styles makes for a unique piece of Philippine architecture, one that can be appreciated by architects and tourists alike.

2 Chapel of Cartwheels

“When spreading religion and the virtues of theology, one has to explain it in a language that people can understand,” Msgr. Guillermo Gaston says. The Chapel of the Cartwheels is the monsignor’s noble attempt to bring religion—usually enshrined in large, imposing structures made of luxurious materials—closer to the farmers that live around and inside their hacienda in Manapla, Negros Occidental.

Msgr. Gaston starts from the beginning: he tells the story of how rubber cartwheels replaced wooden ones, and how they were left in his father’s storage barns to rot away. In a stroke of inspiration, and spurred by his vast interest in design and architecture, he thought of using the old cartwheels for a humble chapel he long wanted to build inside the hacienda grounds. He then enlisted the help of his brother-in-law, architect Jerry Ascalon, for the technical details. The result was a chapel that had a rough-hewn charm, almost as if it was built by the farmers who now arrive there in droves to celebrate mass, as if it was not premeditated or designed by a man of the Church.

“I made the cartwheel a symbol of the Holy Trinity,” Msgr. Gaston says. “The center of the wheel is God the Father, from whom all things come; the spokes are Jesus Christ, spreading God’s word; and the wheel is the Holy Spirit, responsible for our actions and guiding our way.” The round chapel is supported by 16 pillars, which represent the 16 documents of the Second Vatican Council. The roof was inspired by the Filipino salakot, a farmer’s best friend in the fields. Every element inside the chapel has meaning—a traditional way of building religious structures, but graciously made more relatable and accessible by the good monsignor.

READ MORE: Sculpted illusions at the Basilica Minor of Immaculate Conception in Batangas

3 Our Lady Queen of Peace Parish

Traditionally, Philippine cities that serve (or had served) as commercial trading centers have Chinese communities within them. They are often separated from the rest of the community, as centuries of colonial rule deemed them threats to the dominance of the ruling power.

It was no different in Bacolod, the commercial center of Negros Occidental. When the Communist regime in China drove more Chinese, specifically Catholics, to seek refuge in the Philippines, then bishop of Bacolod Msgr. Manuel Yap worked harder to create harmony between the Chinese and the Filipinos, most of whom still had a colonial-minded bias against the Chinese. Eventually, Msgr. Yap’s efforts paid off as more Chinese and Filipino Catholics worked together in their ministry and Filipinos in general opened their minds, overcame their bias and developed closer ties with the Chinese.

As the number of Chinese missionaries increased, the more the Chinese Catholics became active in religious ministry. This led to the creation of the Our Lady Queen of Peace Parish, which now serves as the center of Chinese Catholic life in the city. Indeed, the parish is aptly named as it stands testament to the harmony and peace that now pervades between those of diverse cultures.

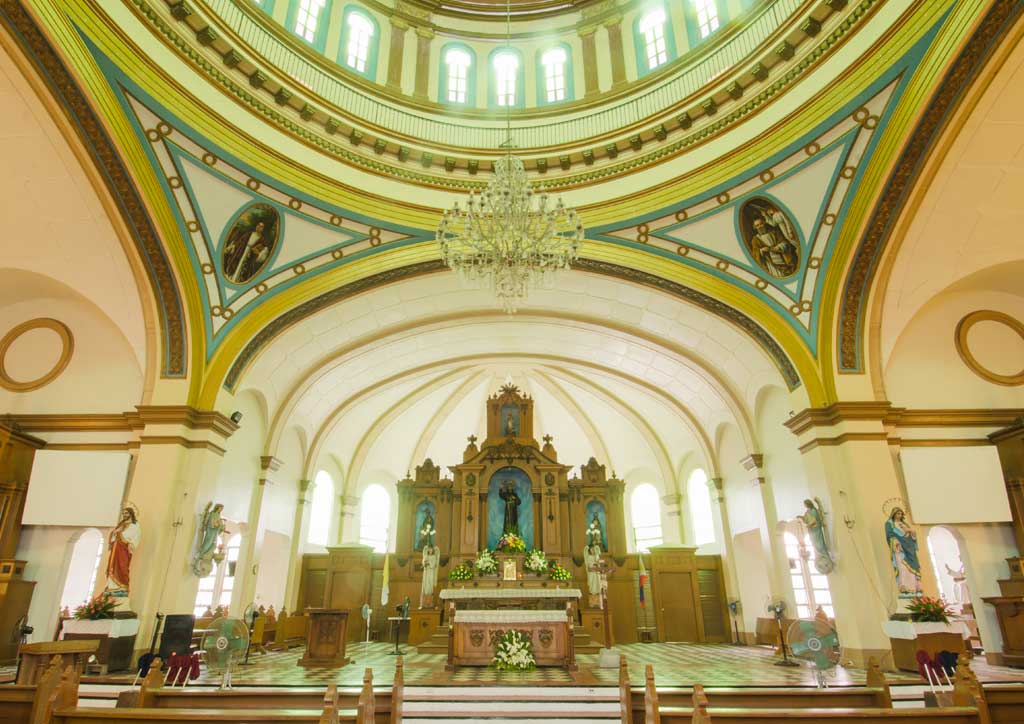

4 San Diego Cathedral

Back in the Spanish era, Silay fancied itself the cultural and intellectual hub of the island—“The Paris of Negros.” In fairness, the community, from its wealthiest barons to humble farmers, gave generously to make the town center—in particular, the church and the plaza fronting it—worthy of the appellation.

By the late 1800s, the church was even larger than the one standing today, with massive walls of concrete and brick, and is said to have been built with voluntary labor. Construction, however, was interrupted by the Negrense revolution against the Spanish in 1898.

The unfinished structure became an eyesore until the 1920s when Jose Ledesma, Sr., volunteered to pay for the construction of a new church befitting Silay and its stately mansions. Several designs were submitted, the winning one by Italian architect Lucio Bernasconi, who also designed the Silay Wharf (sadly destroyed in World War II).

When it was about three-fourths complete, Ledesma conceived of enjoining the parish to pitch in so that people could say they had a hand in building their church. The cooperative effort revived a tradition of giving that remains strong today, as can be seen from the well-maintained cathedral and grounds.

5 Virgen Sang Barangay Chapel

In the middle of the affluent Sta. Clara subdivision in Bacolod City sits the Virgen Sang Barangay Chapel, an unassuming structure more likely to be mistaken for someone’s house than a house of worship. The land that the chapel is built on was donated by Antonio Gaston of Silay, the founder of the Barangay Sang Virgen organization.

The 30-year old chapel stands in stark contrast to the Spanish era churches in the region, in terms of its architectural style and materials used. Instead of a cruciform layout, a simple square structure with sloping roofs was built, reminiscent of a traditional bahay na bato. It can be opened on three sides, only closed off by capiz shell sliding doors that give visitors a preview of the indigenous material the chapel has come to be known for.

READ MORE: Revisit the stories behind 7 heritage Batangas churches this Holy Week

Locals have taken to calling it the “seashell church,” because of its generous use of polished capiz and mother-of-pearl shells collected from the shores of Negros. The Stations of the Cross, the altar, the statues of saints and the 9 x 21-foot mural behind the altar are made from shell mosaics that number in the hundred thousand, all done by a local named Leticia Sia-Ledesma. The use of wood for the trusses and sliding doors combines with the shells to give the Virgen Sang Barangay Chapel a distinct local flavor, making it a unique piece of architecture in the country. ![]()

Original articles first appeared in BluPrint Vol 1 2015. Edits were made for Bluprint.ph.

Credits

Introduction written by Judith Torres

1 Written by Miguel R. Llona. Photographed by John Daryl Ocampo of Studio 100.

2 Written by Sibyl Layag. Photographed by John Daryl Ocampo of Studio 100.

3 Written by Sibyl Layag. Photographed by John Daryl Ocampo of Studio 100.

4 Written by Judith Torres. Photographed by Ed Simon of Studio 100.

5 Written by Miguel R. Llona. Photographed by John Daryl Ocampo of Studio 100