Jaro’s Casa Mariquit, a bahay na bato as graceful as its namesake

Sixteen year-old Mariquit peered anxiously through the gaps in the capiz windows of the sala, which were still closed because it was not yet dawn. It was May 27, 1924, and the early morning air was still chilly. Beads of dew formed a pristine, filigreed net of silver over the garden below. The slender heiress was waiting for her suitor, Nanding, to arrive. Did he still want to marry her? Would he come fetch her and elope with her now, before the rest of the household woke up?

Mariquit had heard her mother and stepfather arguing the night before. Apparently, Vicente Javellana did not approve of Nanding, and wanted Mariquit to marry Ernesto, a Ledesma boy from Jaro, who was also a good friend of Nanding and his brother, Ening. Mariquit spent a sleepless night, panicked at the thought of marrying someone other than Nanding. She had resolved to send a trusted servant with a note to him apprising him of the need to elope immediately, but could not help fretting about how her family would react.

READ MORE: The grand Beaux-Arts style now even clearer in Iloilo’s Lizares mansion

Mariquit’s grandfather, Don Julio Quisumbing Javellana, was a hard man. He had amassed great wealth by lending money to hacenderos and collecting the haciendas of those who could not pay their loans. Don Julio’s house was unassuming compared to the mansions of Jaro’s preeminent families, the Benedictos, Jalbuenas, Jaladonis, Arguelleses, Montinolas, and Ledesmas.

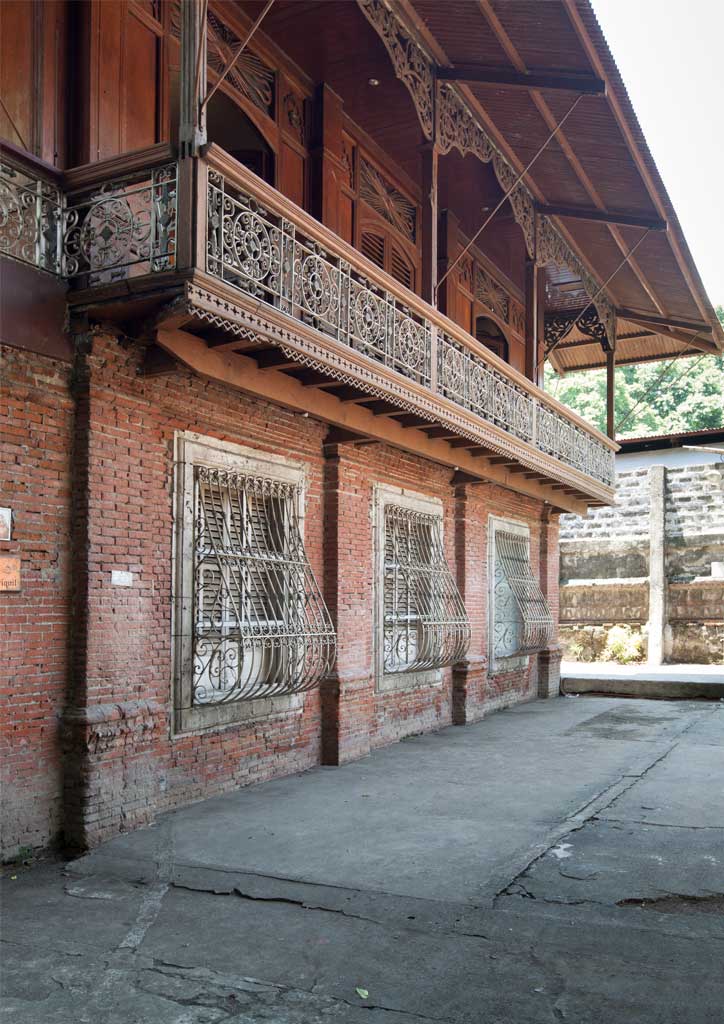

Other than the fine grillwork of the balcony out front, the house looked rather ordinary. It was a typical though well-made bahay na bato, a wooden house with sliding capiz windows built on sturdy, 30-foot long haligi buried deep into the ground. Plastered brick walls formed a solid skirt around the haligi, enclosing the silong. The silong was where the Don conducted his business, and when the Don had a metal vault installed in 1910, the Javellana silong was a veritable bank.

If the exterior veered towards the plain, the private spaces upstairs showed more concession to status and luxury. Thick, long, and lustrous planks of Philippine hardwood were used for the floors. Doors were of solid yakal, and the fretwork or callado above them—solid pieces of wood carved in the shape of flowering vines emanating from urns—were exquisite.

The cutouts above the doors combined with the ventanillas and wide windows on all sides of the house kept it well lit and ventilated. Generous eaves and the steep terra cotta tile roof kept the interiors shady and cool. The Javellanas, like the wealthiest of families in Iloilo, owned a telephone and a gramophone.

Relief washed over Mariquit when she saw Nanding finally arrive. She slipped out of the house and out the gate as quietly as she could. She was ready to begin a new life with her only love, the young man she had known since she was ten, and he, fourteen; a promising law student who would become Iloilo City mayor, senator of the Philippines, senate president, secretary of agriculture, and vice president of the Philippines for three terms, Fernando Hofileña Lopez. Together with his elder brother, Eugenio Lopez, Toto Nanding would build a vast industrial empire that included Meralco, the Manila Chronicle, and the ABS-CBN Corp., for which he served as chairman from 1986 until his death in 1993.

Mariquit and Nanding did not stay in her ancestral home. Nor did she retire there after her husband’s death. The memories of Nanding in the sala come a-courting; of that fateful night when she overheard her parents arguing in their bedroom; and the frantic and exhilarating morning after when she ran down the steps to elope with him were just too bittersweet.

Life with her husband of 69 years was eventful, at times intense, and often in the public eye. “I had to transfer to a small house that Nanding built for me, as it is the one place where I have the least memories of us together,” Mariquit, newly widowed, explained in a Manila Chronicle interview. She added: “I had been so dependent on Nanding that up to this moment, I still wish that I was the first to go.”

READ MORE: Spanish, Chinese, Muslim, and Filipino motifs in Casa Sanson y Montinola in Iloilo

Robert Lopez Puckett, a grandson, inherited the house and started its restoration soon after his grandfather died. Workers carefully chipped away at the old lime plaster covering the ground-floor walls of the 200-year old house to expose the ancient red bricks underneath. Unfortunately, that is one of the worst things one can do to historic masonry. Water penetration is the most common cause of decay in old houses, which are most vulnerable because the bricks and mortar used to build them are much more porous and permeable than modern-day materials. Damp walls promote the growth of algae, moss, lichen, and fungus, which hasten the deterioration of the walls.

Fortunately, the grandson did not commit the even more grievous error of covering the old bricks with cement, sealant or waterproofing, which many people think protect aged masonry. Local and UNESCO conservationists who wrote the Heritage Homeowner’s Repair Manual for Vigan explain that traditional lime plaster and mortar provide the best protection for traditional brickwork because they are “weaker and more permeable than the bricks out of which the walls are made,” and allow the walls to breathe, and damp to evaporate.

Lime mortars is intentionally weaker so that it will break or erode before the building blocks do. Being much cheaper and easier to replace than historic bricks, lime mortar is, in conservation language, the sacrificial element in masonry. In contrast, the use of modern cement, which is hard, impervious, and inflexible, guarantees that it is the precious old bricks that will soak all moisture, erode, and break first.

READ MORE: What was Vigan like before the UNESCO Heritage fame?

During BluPrint’s visit to Casa Mariquit in 2016, we saw no outward signs of deterioration in the silong. The wooden floors upstairs, though, are not level, and the floor in the dining room is particularly bowed. We romanticized it on our visit seven years ago as testament to the many large family dinners hosted in the room, the table groaning under weight of Iloilo’s tastiest delicacies cooked in the adjacent cucina and azotea. It would be wiser, however, to take stock of the deformity with a clinical eye. Has uneven settlement of the ground caused the foundation to crack, and one side to list? Have excavations and drilling for deep wells in Jaro over the decades lowered the water table, and caused a part of the house to sink? Or, perhaps it is not foundational but structural, such as one or more haligi starting to fall prey to moisture and pests?

Casa Mariquit otherwise appears to have benefitted from regular attention. The house and its contents are still dusty, but no longer blanketed with grime, the contents of each room now thoughtfully chosen and rearranged. The profusion of photos and memorabilia from Nanding’s political career still might make one mistake the house as a Lopez ancestral home. But the house honoring Mariquit’s gentle and graceful spirit now resonates more clearly with her memory. ![]()

Original article first appeared in BluPrint Special Issue 3 2016. Edits were made for Bluprint online.