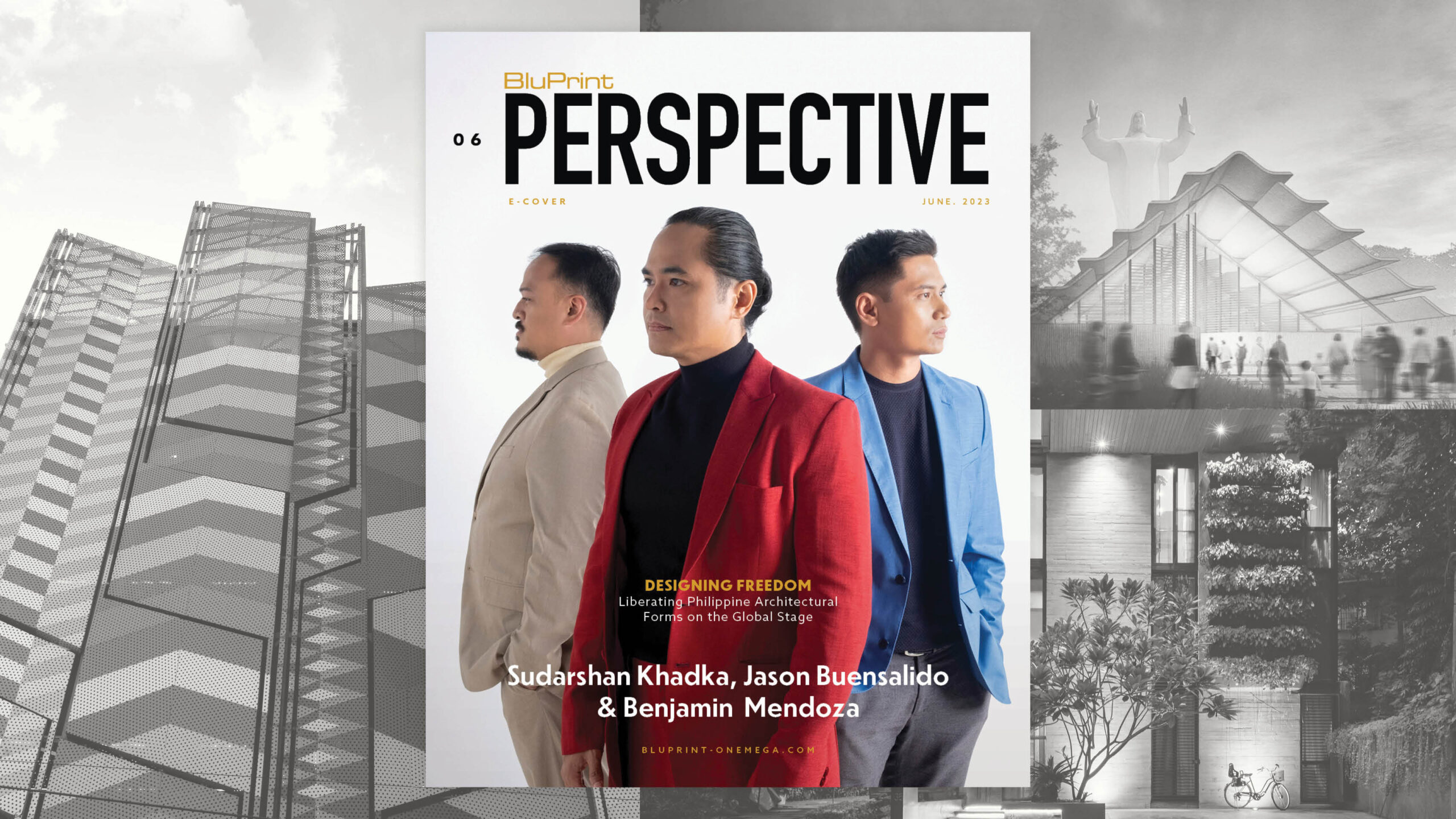

Designing Freedom: Liberating Philippine Architectural Forms On The Global Stage

“The test of true indigenous Filipino architecture…is involved with the pursuit of universal design solutions by using native insights into the problem.” This was once said by National Artist for Architecture Francisco Mañosa. For a long time now, there has been the idea–a stereotype, really, that Filipino architecture isn’t Filipino architecture if it doesn’t look like a bahay kubo. But the bigger picture is that Philippine architecture has evolved past that idea just like how every other culture and everything in it evolves. Philippine architecture now has absorbed other concepts from foreign neighbors while mixing them with traditional Filipino ones.

What are the stereotypes against Philippine architecture?

The idea of stereotyping sadly still exists in all aspects of life and is a habit one must strive to dissolve as time passes. In architecture, it exists in the thought that architecture now can’t be a combination of both, that architecture–like the other things people judge–has a solid and unchangeable definition. The notion however that local architecture is limited to looking completely traditional or vernacular pulls down the essence of evolution and is a contrast to what Philippine culture looks to be today which according to Jason Buensalido, Chief Design Ambassador of Buensalido Architects and Barchan Architecture and Design, seems to be “about variety, freedom of expression, and plurality in expression especially in relation to the built environment.” for them, this rigid stereotype is one that they all strive to dissolve with respect to different cultures within the Filipino culture.

“We must dissolve the notion that Philippine architecture is limited to traditional or vernacular styles.” Sudar Khadka, partner at LVLP and Khadka + Eriksson Furunes says, “The bahay-kubo and the bahay-na-bato are essential parts of our architectural history, but it is equally important to value and draw from the whole breadth and evolution of Philippine architecture.”

On one hand, designing in the new age is a balancing act. In a way, it’s like how other countries like Japan, Korea, and China are able to mix the traditional with the old. Sometimes, vernacular architecture pops up in different places, while other places are designed with architecture that embraces the modern age while still thinking of the country’s climate and culture. Like these neighbors, new Filipino Architecture still has to make a balance and return to its roots, to be connected in some way to the forms, uses, and materials that come from the old customs and traditions from the past. For Benjee Mendoza, co-founder and Principal Architect of BAADSTUDIO, local architecture must perform better in the local context by creating designs that focus on the country’s setting and climactic needs and don’t just borrow foreign design attributes for the sake of aesthetics.

“We can learn from a number of exceptional architecture that great Filipino architects have built for us to learn and be inspired with.” Benjee says, “Although there have been some evident misconceptions in our contemporary architecture that shows designs inspired by foreign concepts which are not beneficial to our local conditions. We in the studio try to discuss our mistakes like everyone else, try to understand how we can design and execute for the better, and in the end make compelling architecture that is relevant to our local context.”

Though the same traditional ideas work as the project’s soul, they’re shown in different forms that have adapted to the current times as demonstrated by the projects made by three of this generation’s top local architects. With these three architects, we are able to see how far Philippine architecture has evolved and how much further it can go when given the right direction, support, and passion.

This Generation’s Big Three and Their Projects:

Sudar Khadka is currently a partner at Leandro V. Locsin Partners and Khadka + Eriksson Furunes and was one of the Philippine winners who represented Leandro V. Locsin Partners (LVLP) and was one of the Philippine winners at the 2017 World Architectural Festival in Berlin. Most recently, Khadka is known as the co-curator of Structures of Mutual Support, a library and conflict mediation space that became known in the Philippine Pavilion at the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale. It was made with Alexander Eriksson Furunes and built with the Gawad Kalinga Enchanted Farm in Bulacan. In this project, the idea of bayanihan was married to the maaliwalas concept through bright, open, airy, light, and well-ventilated spaces that capture the essence of what beautiful Philippine architecture can be.

Related read: The Philippines’ Architectural Triumph at the Venice Biennale 2021

Alongside this groundbreaking project, Sudar also dives into residential projects like the Shear Wall House–a 175-square-meter plot for a family of eight. Designed to be a retirement home, the Shear Wall House is a functional and user-oriented house that’s earthquake-proof due to its proximity to a fault line 30 meters away.

Lean, enduring, and hardy against the elements, it was the result of Sudar’s era of experimentation with concrete and was completed after five years of construction, resulting in a bare-boned but beautiful home that uses the strength and durability of shear walls and combines it with an abundance of interior details and textual flourishes that add warmth and character to the home. Among its many notable features is a lightweight wooden staircase that elegantly combines wood and steel and has a solid feel as little to no vibration occurs when the steps are used.

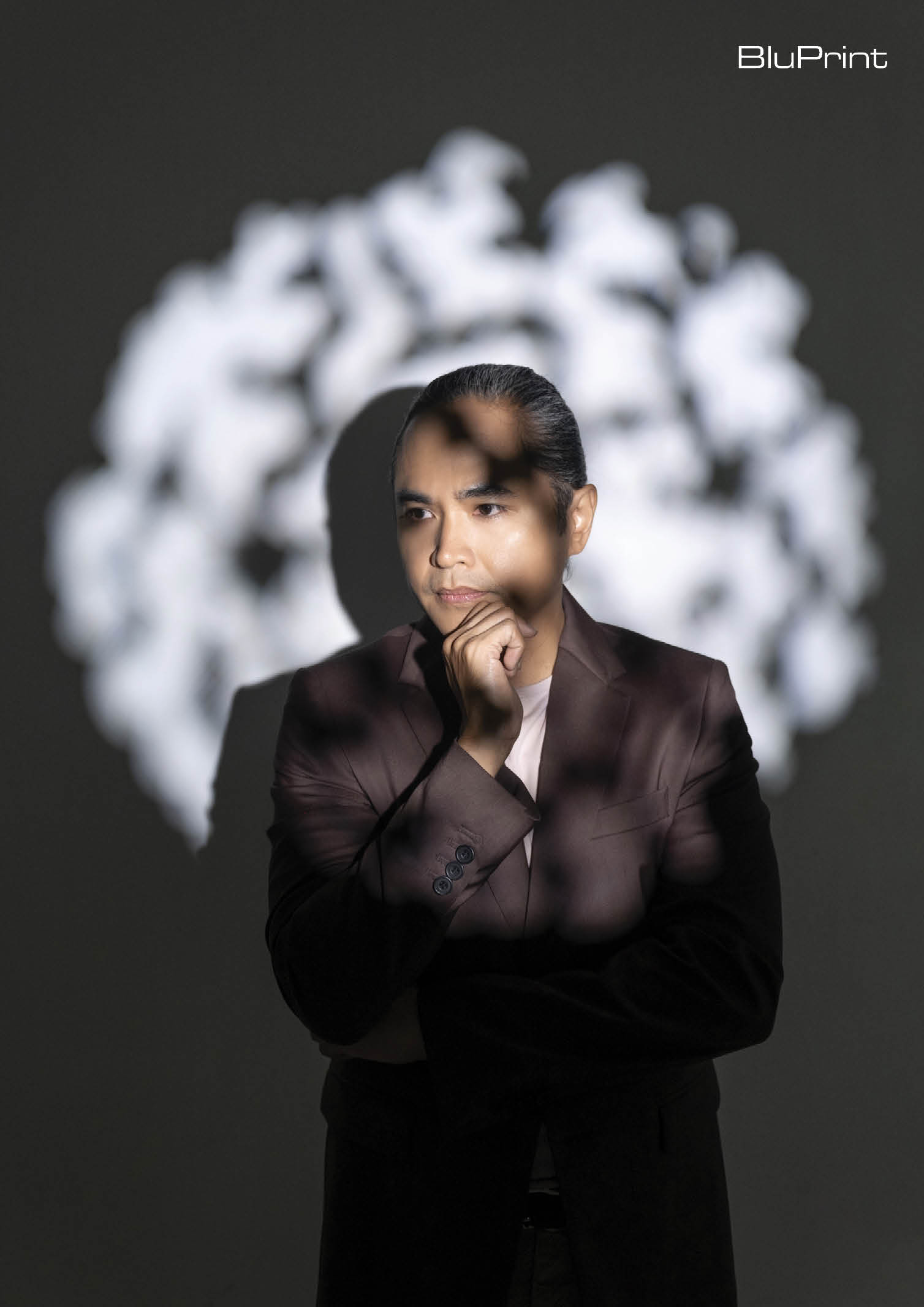

Jason Buensalido is the Chief Design Ambassador of the award-winning firm Buensalido Architects and Barchan Architecture and Design. Known for their bold and innovative concepts, Buensalido and this 17-year-old firm has created a plethora of projects ranging from residential homes and commercial work to hospitality and institutional projects. One of these is the CIIT Interweave building which was previously an old four-story building that was reused and transformed into a richly colored and dynamic structure that presents freedom, creativity, and the journey toward innovation.

Related read: #NewPH: Jason Buensalido’s Vision of a New Philippines

With this concept expertly shown through the design, the building won citations as a Highly Commended Project Completed Buildings-Schools Category and The Best Use of Color Category from the 2021 World Architecture Festival (WAF). Aside from its colorful facade that gives a nod to Philippine textiles, its interior industrial style is also mixed with abstract Filipino weave patterns and energetic hues that embody the vibrant zeal of Filipino culture while giving the interiors a sense of movement and warmth. Probably its main and most notable feature is the centralized staircase which doubles as a social space since it serves as an amphitheater where students can have huddles, lectures, and even just hang out.

Benjee Mendoza, Co-Founder and Principal Architect of BAADSTUDIO has been a juror for the World Architecture Festival (WAF) for four times now and is known for crafting projects that won WAF awards like the Sunken Shrine of Cabetican in Pampanga, which won the category in 2017. Alongside this project is The Pilgrim Shrine which has been shortlisted in the 2022 World Architecture Festival (WAF)’s Future Project, Civic and Community Category.

A project that took the idea of a bahay kubo and clothed it in steel armor that could withstand storms and time, the shrine was a rebuilding project for the previous bamboo structure that was swept away by typhoon Ursula and serves as an inspired project made to honor the pilgrims’ devotion to their faith. Taking the general shape of the old nipa structure, the new shrine’s pitched roof is made of gracefully curved layers of concrete that were reminiscent of nipa while still giving it the strength needed to withstand tropical storms.

Related read: BAAD Studio designs an enclosed open house

Whether it be through durable designs that take note of the site’s natural hazards, balancing a culture’s key traits through energetic visuals with modern solutions, or remembering and admiring the beliefs of a client and highlighting them through a new work that still carries the old design, we can see the progression of Philippine architecture inching free of the stereotype it’s been boxed in through designs that keep the country, its people, and its key traits as the project’s most striking elements.

How do we break free from the stereotypes against Filipino architecture and stand out globally?

Benjee Mendoza: “I would like to believe that the architecture community is not very hypercritical. It has been evident that great architecture around the world may they be coming from first-world or third-world countries resonates well with their local conditions-promoting their local history and sense of place. If we can only strive to protect our heritage architecture better, and create works in a similar caliber of compassion and meaning- we should end up in a good place. We have always thought that we should focus on the work, and the rest will follow.”

Sudar Khadka: “The stereotypes against Filipino architecture primarily exist in our minds. Breaking free from that requires us to break free from our own self-imposed limitations. Changing the world begins by changing the way we think about the world.”

Jason Buensalido: “Doing the work. This means developing your skill set as an architect–developing your theoretical and philosophical foundations and getting to know yourself because in doing that you can create an authentic response to any architectural problem which always leads to an authentic and appropriate solution. It’s a combination of authenticity and appropriateness towards a particular design problem that can spur out quality architectural solutions. Combining that with experimentation and curiosity towards something new, to detach from something formulaic, I think we will be able to break free from stereotypes against Philippine architecture.”

Progress never stops. In light of the future, it’s essential that we’re able to collaborate with other architects and designers around the world to bring more ideas into the mix.

“We should be collaborating with as many architects and cultures as possible so that we may draw upon the full diversity of ideas and technologies available to us.” Sudar says, “Great architecture is not limited by the geographic or political boundaries we choose to set for ourselves.”

Benjee Mendoza agrees, mentioning the country’s neighbors for future collaborations. “Maybe our ASEAN brothers and sisters. Which we are currently working with architects from Thailand now developing local projects in Manila. Through this, we have been learning a great deal in sharing our experiences and differences.”

To Jason Buensalido, collaboration should happen with anyone who wants to collaborate.

“By doing so, there’s tech, culture, and knowledge transfer. Anyone who wants to collaborate with us…we should be humble enough to see it as a learning opportunity and not a threat to us. And maybe an attitude that we can learn from others is the pursuit of excellence and doing it right the first time. It’s a counter to the ‘pwede na yan‘ mentality which a lot of us Filipinos sadly still possess.”

Freedom means being able to evolve. It means having enough space to create something inspiringly original from something that already exists. By putting expectations on something and branding them as something so rigid, advancement will be a much slower process where possible genius is hindered from shining.