(Euclidean) Planning is dead. Long Live Urbanism.

“Walang Urban Planning sa Metro Manila.”

“Wala namang Masterplan ang Metro Manila.”

“Metro Manila is dead.”

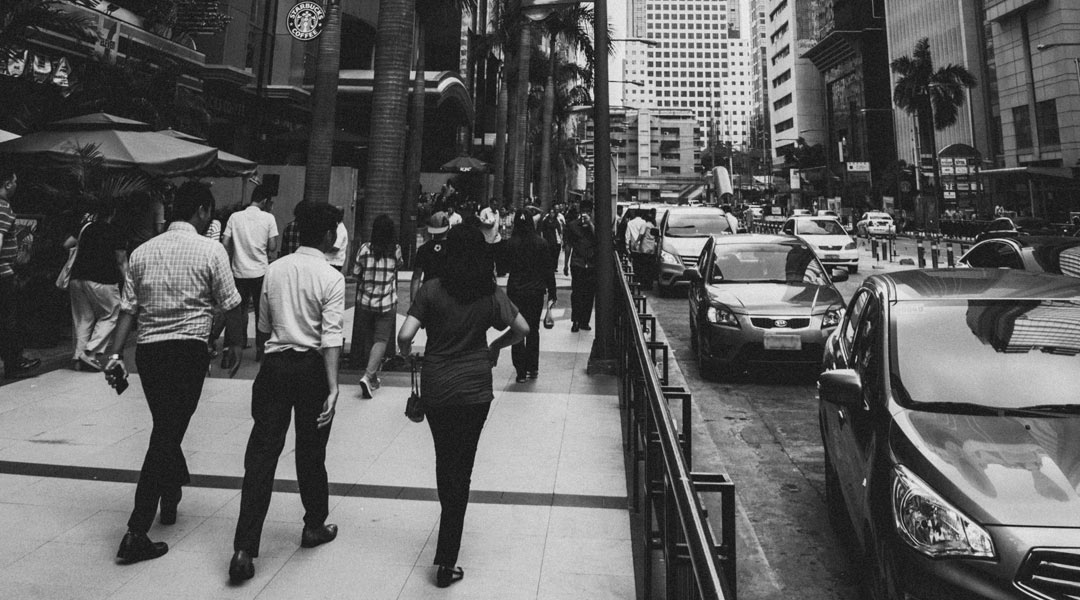

These are oft-repeated truisms, usually when one is stuck in Metro Manila’s bowels: in cheek-by-sweaty-jowl compression in the MRT; hunched over while hanging from the back of a jeepney; balancing buttock cheeks at the edge of shuttle chairs designed for three but seating four (with the mysterious logic of which passenger sits in or out); or in the air-conditioned comfort of the vehicles that were once promises of freedom, mobility, and of having arrived, now unmoving at the hair-trigger red light.

These are said out of helplessness and resignation, out of the inability to comprehend the whole, out of learned and well-traveled indignation, and of scorn for the politicians and their lackeys who have brought us to this gridlock of an urban condition. Heck, they are spoken even by our leaders themselves, often in their latest attempt to empathize with their constituents by riding the MRT during an off-peak hour, the press, bodyguards, and personal assistants in tow.

READ MORE: Design Better Extended: Terminal gardens in Hubilla Design Group’s Ayala MRT station

How we got here: suburban sapin-sapin

We transit from our distant sub-urban homes and communities to our jobs in the CBDs, the good schools on Katipunan and the University Belt, to attractions like the CCP, parks, amenities, and urbane spaces that provide us limited lifestyle options, apart from our pervasive shopping malls.

We feel the stresses of the two-hour commute melt away once we turn into our subdivision gates, from the grand Louis IV incarnation to the nondescript hut with the standard boom and concrete counterweight.

We justify our voluntary imprisonment inside our gated subdivisions and homes because we fear the undesirables. We move to the suburbs to create safe and wholesome living spaces for our families; then we barely get to spend time with our children because we get home late, tired, and worn out by the kilometers-long queue of vehicles and the nightly procession home.

- Our development model has followed the American suburbs. Single-use, color-coded Euclidean planning defines our land cuts and land use. Red for commercial, yellow for residential, blue for institutions, purple for industrial uses, green for open spaces, and so on, just like sapin-sapin (multi-colored rice cakes) or patchwork quilts.

- Pre-industrial cities did not have Euclidean color-coded zoning. In fact, the best and the oldest, most livable cities in the world were unplanned, naturally evolving ‘white sites’ or mixed-use zones. Paris, London, Rome, and even gridded New York, bear the marks of this ad hoc, unplanned layering of different uses. In pre-industrial towns and cities such as these, residents lived above their businesses. The baker sat beside the blacksmith, across the butcher and the pub, all within walking distance of a plaza, square, or rotunda, with government buildings alongside.

- Euclidean zoning came about because town planners realized factories did not make good neighbors for residential communities. The Industrial Revolution blighted cities with noise, smoke, soot, pollution, and disease. Tired, coughing city-folk longed for the romance, peace, and quiet of the pastoral countryside, away from the choking smog and terrible conditions of cities. Planners sought to separate places for production (purple land use) from homes (yellow land use) and created various ways of bringing the countryside into residential communities, from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities to the different forms of Agricultural Utopia envisioned by the first wave of environmental planners. The intent was to separate uses into neat land zones.

- What was once a romantic ideal evolved into a political and economic gesture. Cities were collectives and dark settings, whereas in the countryside one could own his destiny, be free to do what he wanted within his property. From this notion issued forth the suburban vision of America. Frank Lloyd Wright envisioned Broadacres, where each family owned a substantial plot of land to live on and the concept appealed to land speculators and developers who saw the opportunity to sell vast swathes of undeveloped land to the weary masses of city dwellers. They sold large tracts of land beside railway stations at first, attracting settlers from the city with greatly commuted or reduced train fares, thereby creating the first railway suburbs and giving rise to the term, “commute.” This was a time when people were paid (a travel discount) to live far from their workplaces. Now, it is the other way around; people pay dearly in fuel prices, tolls, and parking fees for living outside the city.

- America rapidly suburbanized following the Second World War with financial incentives rolled out by the federal government to provide housing for returning GIs. New industries and businesses moved out to the suburbs as well. This created the phenomenon of “white flight,” where blue-collar African-American industrial workers were left in the cities while white-collar white Americans moved out to their gated communities in the suburbs. This compounded the negative view of American downtowns and cities as nests of crime, drugs, and joblessness, and made the suburbs even more “exclusive,” to keep the scary urban masses—the “others”—out.

- American-style commercialism was a product of mass production, mass marketing, mass consumption, and mass car use, with the car a symbol of freedom, independence, and status. The profligate lifestyle was fueled by abundant cheap oil. Everyone guiltlessly indulged, unaware of the ecological effects of the fossil fuel-driven world economy.

- Shopping malls were first envisioned by Victor Gruen, an Austrian-American planner-architect, as the new ‘downtown’ cores of these new suburbs—clean, crime-free, pedestrianized, climate-controlled, and with landscaped outdoor spaces. People no longer needed to go downtown to shop in America’s cities. However, coupled with Euclidean planning, malls turned out to be a disservice to communities, something planners and enlightened citizens realized decades later. Shopping malls were the greatest beneficiaries of single-use zoning because when people wanted to open small shops or cafés in their neighborhoods, zoning forbade it. Small local stores and businesses were pushed out of the scene, allowing malls to monopolize the market. Euclidean planning creates concentrations of wealth and critical mass—great for starting something from scratch, but bad at distributing development and reducing traffic. Ultimately, Victor Gruen saw his vision for malls morph into Frankenstein monsters “surrounded by seas of surface parking,” and he despised and disowned them for their blatant commercialism.

READ MORE: Phenomenon and Noumenon: Architectural Preservation

Imported suburbanism

Unfortunately, our cities have followed similar patterns of growth. Intramuros was the first gated community, built as a fort to keep out the heathen masses on the opposite bank of the Pasig River. Luneta or Rizal Park and the city grid of Malate and Pasay were planned out of the desire to create a blank slate and break free from the colonial symbolism of the Walled City. These areas were part of Daniel Burnham’s grand vision to create a radial-concentric city grid, which forms Metro Manila’s underlying major street network. The Burnham grid’s unintended stepchild is EDSA—a circumferential road not intended to bear any great significance in the centralizing master plan. See, Burnham meant to concentrate power around Luneta but indirectly ended up creating the framework for Manila’s suburbanization after World War II.

- While we picked up the pieces after the war, we pushed through with the transfer of our capital to Quezon City. Alongside this expansion, new ‘bedroom suburbs’ (suburbs whose residents are predominantly commuters) came to be, patterned after those of our former American colonizers. Manila’s decay was fated despite efforts like the LRT and other infrastructure to revitalize it. Businesses left Escolta and downtown Manila to start afresh in the new suburbs rather than rebuild the ruins. The blank slate was too alluring.

- Those blank slates were planned residential villages and subdivisions, with commercial strips here and there. These gave rise to the Makati villages of Forbes, Urdaneta, San Lorenzo, and Bel Air; San Juan’s Greenhills; Quezon City’s White Plains; Pasig’s Green Meadows, and so on. These gated communities are where Intramuros’ old elite and the burgeoning new business classes came to settle. The developers allocated land for commercial uses for these residents, creating the CBDs we all commute to and from today.

- The subdivision pattern of development was replicated in the outskirts of EDSA, to Parañaque, Las Piñas, Muntinlupa, Cavite, Marikina, Antipolo, and Bulacan. These new bedroom suburbs catered to the middle class working for the businesses in the Ayala, Ortigas, and Cubao CBDs. The new burbs were almost devoid of amenities, and residents had to drive to Makati, Cubao, and North EDSA to shop or watch a movie.

- Those who can afford, drive. The vast majority take the tricycle or jeep, then get on buses or shuttles, or the MRT and LRT—sometimes three to four different modes of transit to get to work and school. Getting out of subdivisions involves an upstream path into a dendritic or branching road network: from cul de sac to local road, local road to collector, collector to spine, spine to village gate, and so on, with increasing (or not) traffic speeds, carriageway widths, and continuously narrowing sidewalks.

- Eventually, these suburbs fill out. Their main arteries become prime property because all residential-only branches from the main roads provide the catchment of traffic and buyers. All that vehicle and foot traffic is an irresistible magnet to malls, which build along the pathways to large tracts of bedroom communities. They tear up the local fabric, kill the small local establishments, and choke the roads with even more traffic.

READ MORE: Walk through Makati with a British urbanist

Bigger Gates, Taller Fences

Government surrendering development and planning prerogatives to the private sector has led to the weakening of the public realm. We can’t discount that capitalism is still the most efficient way of allocating resources to meet market demands, so long as the market can afford it. But government corruption, incompetence, and lack of foresight have created an enormous housing gap, particularly for low-income families. As more people from the provinces come to our cities, ever-larger clusters of informal settlements form.

And so the middle and upper classes build taller fences to keep our blue-collar brethren away from our subdivisions, away from the sleek CBDs, oblivious to the massive informal settlements straddling the edges of our places of work and homes. These settlements provide the cheap, on-call labor required for 24-7 jobs, construction and maintenance workers, household help, laborers, and so on that our daily existence requires.

The working poor is also the captive market for votes, for publicity, and of face-branded “basic services” of our local governments. Some political dynasties go as far as maintaining the voter registrations of entire relocated slum communities, even after they are moved 40 kilometers away to the many poorly provisioned rows of housing in Laguna, Rizal, and Bulacan.

These same in-city communities are the retaso and seruho of our urban fabric. They are spaces untouched by environmental planners and architects, and ignored by developers—not big enough, not good enough, gets flooded, too political, too cut up. And yet, these same retasos are a vibrant quilt of activity, of localized self-sustenance, and of resiliency.

READ MORE: Did we even learn our design lessons after Typhoon Ondoy?

How do we move forward? Urbanism is living locally.

Living locally means consciously deciding to live and work within a tighter area, instead of traveling long distances back and forth between home and work. Even as we move around our neighborhoods more frequently, the shorter distances make our lives more sustainable. We use less fuel and energy. We walk more and bike more. Longer journeys are less frequent, with higher levels of mass-transit use. Living locally creates more meaningful relationships with neighbors, fostering a better sense of community. The following are ways to make it work:

1. Lift restrictions, allow densification and a mix of uses but guide the free market.

The city blocks of Paris and New York grew from rows of single-family homes. Landowners built denser to meet demand, and the lenient land-use restrictions allowed the evolution of these places into the diverse and vibrant neighborhoods of these cities.

Our subdivision and village gates should not be barriers against mixed land use. They should merely define the porch of our communities, and not keep out the activities that make neighborhoods dynamic and livable. Burgeoning urban villages like BF Parañaque used to be single-use bedroom communities, but as land-use restrictions were lifted, shops, services, and small businesses catering to the large residential catchment area became viable and self-sustaining. Some stores have even become unique destinations themselves, attracting visitors from outside their respective villages! These local businesses add character and contrast to the homogenized menu of fast-food outlets and stores found in our malls. Let’s learn from these examples.

- Review village and subdivision land-use restrictions. As land values rise, properties within villages become too valuable for their original zone In the exclusive gated villages of Makati, San Juan, Pasig, Mandaluyong, and Alabang, single-family residences and villas will eventually become high-end luxuries hard for nuclear families to maintain, sell, or keep as rental assets. This phenomenon is happening even in what were once middle-class subdivisions, as original settler families move out of bedroom suburbs to be closer to schools and places of work, or to scale down as couples leave empty nests or age. This drives the conversion of villages into rental housing communities. In some cases, houses are illegally converted into dormitories for the waves of foreign (Korean and Chinese) expatriates coming here to learn English and work in the Philippines.

- Identify strategic avenues and intersections inside subdivisions, which can serve as spines or nodes for possible commercialization. Allowed uses can include small businesses, food and beverage outlets, services, co-working facilities, and even remote office branches for bigger companies. The aim is to provide local choices for resident entrepreneurs, customers, and employees. Instead of commuting or driving out of the subdivision to transact business, walking or biking to the neighborhood grocer or café is an attractive alternative. Unpacking some of the concentration of commercial activity from our CBDs into the suburbs would automatically reduce the supply of the traffic flowing back and forth between them during the day.

- As developers convert more post-industrial lands into residential towers, the more they exhaust land supply and exert pressure on the surrounding residential communities to densify and build taller. Like compounding interest, this force could grow compelling enough for residents of exclusive villages to vote in favor of the densification of their communities.

- Of course, design, density, and scale restrictions will have to be reviewed, and buffer zones defined. This will require the work of dedicated village administrators and associations interfacing with the city and local government units. Many people will complain and say, “Not in my backyard!” But change is inevitable, and market forces will prevail in time.

READ MORE: How an act of resistance reinvented the Western Bicutan Tenement

2. Move away from single-family residential housing. Diversify communities to include different income levels and forms of housing.

- Healthy cities require a mix of residents from different income levels. Therefore, bring back onsite socialized housing requirements. In the 1970s, the government required developers to allocate a percentage of their onsite inventory for socialized housing. But developers succeeded in getting this requirement amended in the mid-80s, with the government allowing big developers and mass-housing developers to trade socialized housing inventory requirements between them. This has worsened economic segregation and ghettoization of socialized housing projects far from people’s livelihoods and amenities in the cities.

- Conversely, the government can require developers to provide proper housing for a certain number of in-city residents of certain informal settlements in exchange for the socialized housing capacity requirements.

- Review housing building types and occupancy. Single-family homes remain the dominant type of housing in our suburbs. It’s time to consider three-story walk-up townhouses, and five to eight-storey apartments with elevators as a means of moderate densification to harness the rising land values of our suburbs, particularly along village main avenues and spines. Landlords and developers can aggregate lots as they become more valuable and ripe for development.

- Consider new forms of dwelling ownership. Germany is known for having a very low rate of homeownership, with 60 percent of the population being renters instead of homeowners. Most of them value mobility over the property, to relocate easily to where the jobs are most plentiful. Our developers are still selling well but should the bubble burst, their unsold inventory could become a considerable asset as rental housing. Abroad, developers are experimenting with property purchases, which give buyers the right to occupy units located in different housing estates around the city or country, instead of the traditional transfer of the title of one property to the buyer. This is a step up from being mere tenants to secure transients, allowing people the mobility required by today’s modern economy, while providing the security of property ownership.

- Consider new modes of land or property ownership. In Singapore and Hong Kong, with very scarce land resources, the government identifies critical parcels and instead of selling them, earmarks them for development under 99-year leaseholds. The 99-year lease allows for profitable development and use, but also enables the government to revitalize the developments after they have outgrown their useful lives. This is legislated urban land recycling and creates new blank slates of land for government to densify later and improve.

READ MORE: How do we make sure Asia’s megacities are healthy cities?

3. Learn from shopping malls and business districts. Inject their templates into the suburban fabric.

- Distill the contents of the typical air-conditioned shopping mall and lay it out on a walkable and accessible ribbon inside the communities that serve as the catchment of those big malls. Open, pedestrianized places, and al fresco environments like Bonifacio High Street or Nuvali’s Solenad are proof that with proper urban and landscape design and shading, open-air pedestrian retail and F&B strips can work in the Philippines.

- Encourage satellite CBDs or Planned Unit Developments in the suburbs. Apart from malls, local governments should work with developers to bring offices, industrial parks, hotels, hospitals, and schools out to the suburban bedroom communities to create local demand for jobs. These will help prime up local land values and initiate the conversion of single-use, low-density residential suburbs. These will eat up demand from the primary CBDs and reduce traffic as more people choose to live and work locally instead of spending much of their waking hours

- Learn from how Business Improvement Districts work in the US and UK. BIDs are political, economic, and urbanism initiatives that identify the conditions that make shopping malls so successful, and implement them on a city scale, converting streets into vibrant shopping districts. Some developers have applied the shopping mall formula into their own urban developments from scratch. One successful example is Bonifacio High Street, where the mall is part of the city. Old provincial town squares, main streets, Manila’s Escolta and the surrounding plazas, the Avenida-Rizal corridor, Intramuros, and Binondo are all ripe for gentrification. Gentrification has its opponents, but it is better than letting entire districts suffer death by irrelevance and economic decay.

READ MORE: Iloilo’s Calle Réal shows Escolta how it’s done

4. Rethink transport and connections to help aid the transition from suburban to urban.

- The challenge is getting more people to walk than drive. Raising taxes on cars is a start. Eliminating mandatory parking minimums for new developments would discourage car ownership while permitting point-to-point transport like Uber and Grab will make it convenient for people to live in denser cities without cars.

- For mass transit to succeed, let people walk the first and last five minutes of their journeys. Bring transportation out to the suburbs. The problem with most of our suburbs is the residences are so spread out within their villages. People still need cars to get to the transit stop. Harness the prevalence of suburban shopping malls as jump-off points for park-and-ride journeys. Encourage mall operators with incentives to allow car riders to park in their malls in exchange for a minimum purchase of goods from their stores. This will encourage people to leave their cars in their localities and take public transit to the CBDs. This is an excellent way to mediate the transitioning nature of our urban fabric while waiting for suburbs to prime up and densify.

- Harness web connectivity. Too many man-hours are wasted on face-to-face meetings that could have been settled with an email or group chat. As millennials mature into more senior roles in business, they will be more comfortable with screen communication than previous generations of business leaders. The need for full-blown offices outside of production and onsite coordination will diminish if thinking and coordination work is done online. Online communication should help us stay in our localities.

READ MORE: Para! Check out these kooky gadgets for your next Jeepney ride

5. Change our values.

All the above require political will to execute. And control. Carrots and sticks. Enlightened leadership. And a magnanimous private sector. All of which are beyond the lone citizen’s control. Ultimately, our values need to change. It’s time to revisit our beliefs and worldview and reassess whether, in this time of climate, social, and economic change, we should still be holding on to them.

- Bring back the teaching of basic urbanity, civic duty, and neighborliness in primary schools. City living is a collective exercise. It doesn’t work when people don’t understand the consequences of their actions—throwing rubbish on the street, not recycling, playing music too loud, and so on. Despite the criticism of Lee Kwan Yew’s social engineering of Singapore, he changed their mindset from backward to modern through education and the public housing he provided his Sir Winston Churchill did say, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

- Teach urbanism in architecture, landscape, civil engineering, and planning schools. Unfortunately, most of our schools still teach Euclidean planning as an ideal. It’s time to rattle the orthodoxy out of the suburban model, and move away from Western-centric urbanism as our model. By teaching urbanism to the next generations of built environment professionals, we sow the seeds of better buildings, better infrastructure, and a more sensible environment. A more open and distributed urban fabric may even distribute the practice of these professions from being concentrated around large corporate developers to smaller builders and landlords.

- Reevaluate landed homes as assets, and mobility versus Is a landed home as valuable an asset when living far away from work eats into your real assets of time, health, and energy?

- Weigh green suburbs against green cities. Just because you see trees doesn’t mean you live in a green community, especially if it means you have to drive an SUV for hours to get to it. Green cities are green when they consciously minimize environmental impacts by reducing energy, water, and food consumption; when they reduce waste, carbon emissions, methane and pollution; when they expand recycling; when they increase housing density while expanding open spaces; and when they promote sustainable local businesses. Manhattan’s Central Park aside, the island is considered one of the greenest urban settlements in the world because of how dense and walkable everything is from each other.

- Cars: essentials or status symbol prosthetics? Mobile air-conditioning aside, can we make do without them if we lived more locally with better transport options?

- Gated communities. Just how secure do those gates make us?

- Land use restrictions. Just how well do they improve the land values of our suburbs?

We are on the cusp of broad change in our cities and suburbs. It will take time to transition, especially when people (like myself) know of nothing else apart from suburban living. Urbanists are using new research and quantitative measures to investigate cities. Cities are becoming smarter, and soon these methods will guide and enable the invisible hand of markets to make cities better.

Single-use Euclidean planning is a product of the tools and macro scales of the past. Planners had to work on drafting tables and look at scales of 1:5000 and 1:10,000 meters. Planners didn’t have the technology and layers of information now available to help inform a finer, more tactical approach to development. Today, planners are increasingly using Big Data to inform their initiatives. We now have the tools to go into finer-detail planning—not just on the ground level, and in between buildings but also on multiple floors!

READ MORE: Hyperloop is a transport system that will allow people to easily commute great distances

Planning a city should not be like cutting up and assembling sapin-sapin, nor even like layering a cake. High-rise condos over parking and retail podiums are cakes. Rather, planning a city should be more like slow-cooking a stew of meat and vegetables for hours—that is, decades for cities, no short-term plans. Just as the prime cuts of steak are priced and served as fine-dining, our CBDs and big estates are driven by developer interests. To moan about the lesser cuts of meat we are left within the suburbs misses the point that the most flavorful dining experiences are from cultures that use these cheaper cuts and combine them with diverse ingredients into stews. Chop them up and leave them alone to grow in richness and flavor. Our suburbs have been cut up into small parcels. Let’s season them with freedom and inclusivity, and let them stew. Turn them into our caldereta.

The richness of a succession of micro-urban experiences is what the best cities in the world have to offer. And these come about with the coalescing of individual and unique uses mixed together in a self-organizing way, with authorities creating the framework for smaller businesses and communities to flourish, whose flavors are allowed to blend with one another.

We should step away from the standard, homogenous, and sterile, and move toward the fine-grained, vibrant, and locally relevant.

(Euclidean) Planning is dead! Long live Urbanism!![]()

This article was first published in BluPrint Volume 1 2018. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

READ MORE: BCDA Pres tackles USD 5 billion New Clark City, white elephants