Nothing token about passive cooling in Formwerkz’s Open House

“We had to decide how we wanted to live as a family,” says architect Gwen Tan, who designed the house. “We enjoy plants and nature. Berlin and I decided we would not survive happily in a closed environment.” And so the Open House is open, with only grills, slats, and a motorized sunscreen (that still lets in the sun) to shelter the second and third levels of the front façade, and sliding windows and doors on every level at the back façade.

Many folks will say they like the idea of raindrops falling on their face. But not inside the house. A lot of people will also like the idea of an indoor pool in their residence. But not a noisy bunch of wet kids trooping to the master bath to shower after a swim. And almost everyone will profess a desire for cooling breezes in their home. But not if it spells exposure to the dreaded Indonesian haze—an air pollution problem Singapore suffers when smoke blows in from forest fires in Sumatra and Kalimantan.

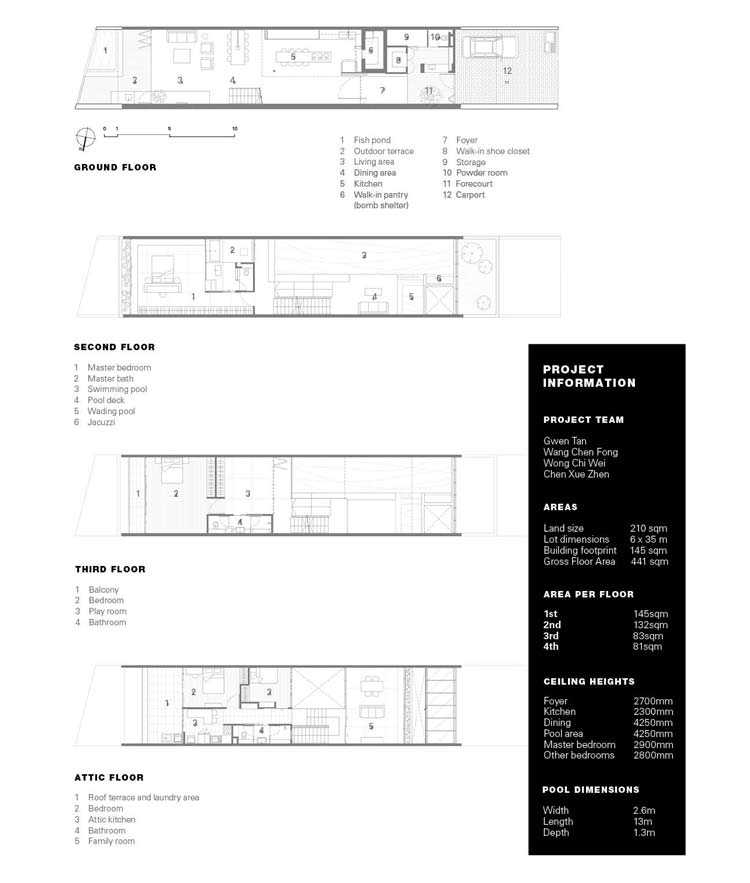

The lot is narrow and long—6 by 35 meters. Tan and her husband, Berlin Lee, both architects and partners at the Singapore firm, Formwerkz, were looking for bigger units, but they fell in love with this particular row of terrace houses because the back looks out to a field of mature shade trees. Tan explains further: “Usually, in the landed housing scene here, the back of your house stares at the back of another house. It’s rare to have this kind of breathing space.”

The big idea was, with few and operable partitions between the front and back of the house, air would wash through the entire length of the unit. The even bigger idea: A swimming pool on the second floor would provide endless enjoyment for the family while cooling the air passing over the water. The living spaces and bedrooms would enjoy this cool air, which, as it collects heat, would sweep up the 7-meter void over the pool and exit through an open skylight.

Given the orientation of the house smack-dab to the west, the openness of the front façade seems like madness. But then, Tan’s spatial organization is brilliant. “We had to deal with the fact that we didn’t want a façade we are always closing up or always drawing curtains and hiding from the sun. So we dealt with it on a planning level. We put the functions that enjoy the sun right up front, and the functions that enjoy the greenery and need shelter from the sun further in.”

The 13-meter long swimming pool goes right up to the front façade with all its openings. So instead of trying to escape the afternoon sun, the family welcomes it, no matter how intense it gets. Elevated from street level and with tall ornamental grasses just outside (planted on the canopy shading the carport below) and a tree in one corner (planted on the ground floor by the foyer), the indoor pool feels very much like a private outdoor amenity.

The organization of the ground floor is both eminently practical and delightful. Tan didn’t bother with windows at the front, as they would only look out to the carport and street. Instead, she lined the first 7 meters of the house with utilitarian spaces: a powder room, storage closet, walk-in shoe closet, and Singapore’s mandatory bomb shelter, currently in use as the kitchen’s walk-in pantry. These spaces insulate the interiors from the heat of the sun beating on the front wall. They are painted black, so they recede from view, and the eye focuses instead on the unexpected and winsome indoor forecourt with a tree. To create the forecourt, Tan punctured a hole in the second floor so the tree—the same one seen by the pool—has 10 meters to stretch upward.

Moving forward into the house, one comes to an open kitchen hemmed by a cooking island whose countertop extends to accommodate informal dining. “Asian kitchens are typically segregated into wet and the dry, but we cook a lot, and we didn’t want to be hidden in a back kitchen. Cooking is a big part of the family, and we all hang around the island. So we celebrate it in that sense,” Tan explains.

Another delightful surprise one discovers moving into the high-ceilinged dining area: the white concrete volume above the kitchen is the swimming pool! A large porthole enables one to see its aquamarine waters—and the people enjoying it if they swim by. If one were observant, he would see the body of water above the kitchen from the little glass window over the cooking area, which lets sunlight shine through the water into the space below.

While in the living and dining areas, people tend to forget that the lush scenery filling the full height and breadth of the end of the room is not the front of the house, but the back. Tan’s 26-square-meter backyard is covered with a wooden deck and holds only a small fishpond, a planter, and a pot or two, but thanks to the trees at the back lot, the terrace house revels in a luxuriantly verdant scene that changes in the course of the day and year.

The bedrooms are stacked above the living area and face east to enjoy this view as well. “In the afternoon, dozens of kingfishers, toucans, parrots, and hornbills fly in and snack on the fruit of the sweet tamarind trees,” says Tan. Tan’s mother shows us a picture she took on her cell phone of two hornbills perched on the balcony rail outside her grandson’s bedroom. “See? It’s just one giant bird buffet here!” Tan laughs. If the unsightly back-of-house service areas are not at the back of the house, where are they? Why, at the top of the house! As we make our way up, we visit the bedrooms, inspecting how natural ventilation works at each level.

The design of the master bedroom and bath is a story in itself. The short of it is, Tan’s husband, Lee, came by the construction site one day and criticized the proportions of the rooms. Tan’s redesign shows her nimble mind and also the progressive parenting style Tan and Lee subscribe to. The shower stall of the master bathroom faces the pool and is accessed from the pool deck by a gently sloping ramp. The idea was for their son and his friends to be able to shower after their swim without entering the master bedroom. Kids may wait their turn outside the master bath at the long, L-shaped ledge intended to keep people from falling into the pool. But kids are kids, and they often get up on the ledge to jump back in. “And they take every opportunity to do so!” laughs Tan.

The bathroom’s sliding glass partitions allow Tan and her husband to look out to the pool area from their bedroom. When the windows of the master bedroom and the bathroom partitions are open, fresh air from the field at the back crosses right through, continuously cooling the bedroom and bath.

One heart-warming surprise is the genial arrangement on the attic level. Tan’s mother and the family helper both have bedrooms up here and share a bathroom. They have a kitchen that allows the mother to cook her own food if she so wishes. The laundry and clothes-drying area is out on the roof deck. Also on the deck, sheltered by thick netting and a canopy, the two women have a running competition to see who can grow the healthier, more beautiful, rare ferns. The roof deck catches strong breezes and overlooks the field of trees, making the setup a pleasant place for quiet time after a long day’s work.

The Open House isn’t just literally open to sun and air. The generous vertical spaces connect the different levels, enabling effortless contact and communication. “It’s very easy for us to find and hear one another. The sound gets amplified. Like, if I’m swimming, my mom just comes out of her room, and she can have a conversation with me. Or when it’s time for dinner, it’s easy to call out to my son from the ground floor,” says Tan.

In retrospect, Tan and Lee’s Open House is a faithful demonstration of Formwerkz’s manifesto to make architecture that “recovers mutual human relationships and restores the primordial relationship between man and nature.” Says Tan of her design process: “It was a lot of experimentation with different typologies. We are always keen to explore every house as though it is the first one we are doing. When it’s your house, you give yourself more time to explore. Construction took almost two years, which is very long for a house this size.”

Before that, the exploration process took over a year and continued all through construction. It was not only because husband and wife are architects who wanted to get things right, but also because it had to be right for the family they wanted to be. “I designed this house,” says Tan, “but Berlin critiqued every bit of it. And it was quite a lot of existential critique!”

I ask Tan what she thinks the effect of growing up in the Open House will have on their son. She replies, “Well, I think he will make this the benchmark of a good house to live in.” Tan and Lee’s son is growing up in a house where trees are prized, where the sun and birds are welcome, where rain spatters are nothing to freak about, where air conditioning is used only in bedrooms and only when needed, and where the faithful family helper enjoys the same amenities as the beloved grandmother.

We know architecture shapes human beings; I say this good house is shaping one good young man.

This article was originally published in BluPrint Volume 4 2017. Edits were made for BluPrint online.