High-Tech Hope for Our Heritage: 3D Scanning by Digiscript

It sounds like the stuff of TV dramas like CSI, but there is 3D data capture technology that can be used to take pictures of a building from which you can extract measurements and spatial information, generate as-built drawings, and come up with 3D digital models.

Unlike conventional methods that capture specific individual points one at at time, a laser scanner developed by Swiss company Leica Geosystems captures rich details of the entire scene, just like a camera taking a 360-degree photo, but with an accurate position for every pixel, so the resulting scans have none of the distortion common in 360-degree images.

So how does it work, and what are examples of practical applications?

[one_half_last padding=”0 0 0px 0″]

Accuracy of High Definition Surveying

- The 3D data capture method through laser scanning is superior to conventional as-built surveys due to its higher level of completeness, better accuracy and quicker availability of 3D as-built data.

- Digiscript’s process captures measurements every 2 millimeters.

- The scanner works through line of sight and captures surfaces and points that are otherwise hard to reach or that may be difficult to access.

- The technology allows for capture of up to 50,000 survey measurements per second, and up to a maximum range of 300 meters.

- The survey points gathered generate 3D coordinate positions for each point and the resulting scan is a set of coordinated measurements commonly known as a ‘point cloud.’

Urban Planning

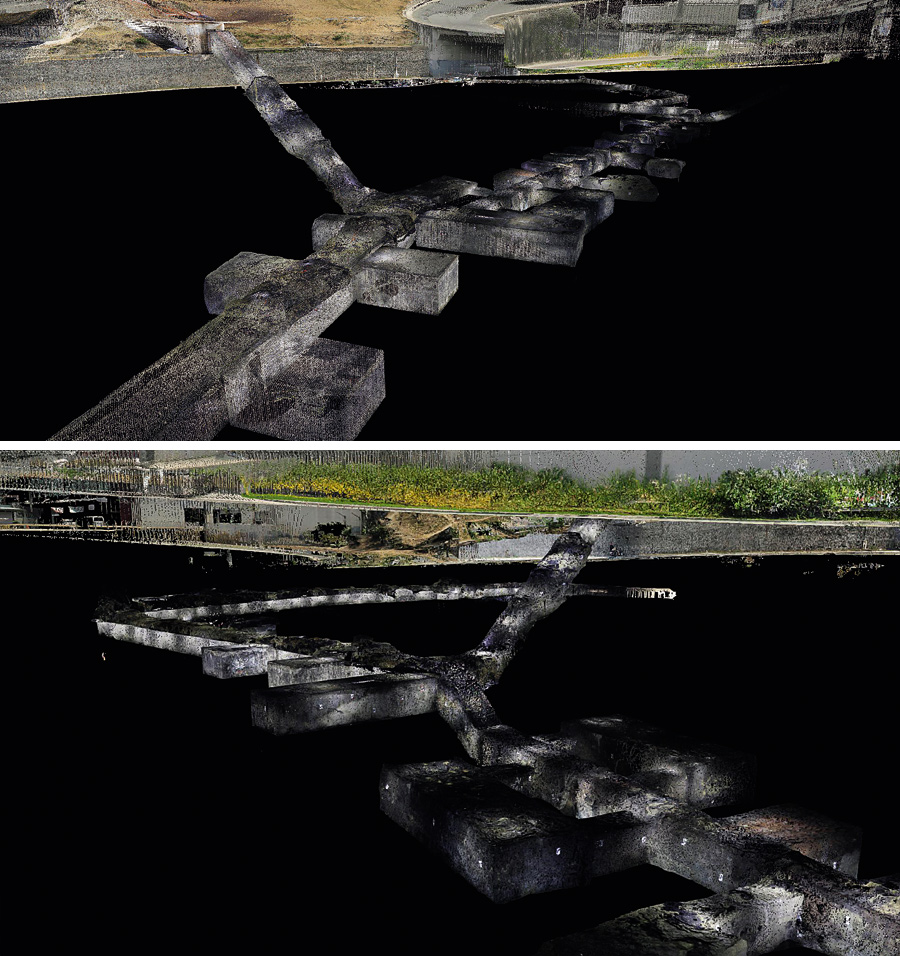

Take the Fort Bonifacio War Memorial Tunnel in Bonifacio Global City. The 2.24-kilometer tunnel was constructed in 1936 as a passageway for military supplies for the US and was heavily used as well by the Philippine army during WWII, then was overrun by the Japanese Imperial Army.

There are plans by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines to convert the tunnel, which traverses C-5 and Kalayaan Avenue, into a museum and tourist attraction in the Fort. To assess the feasibility of such a project, a detailed engineering study (DES) must first be conducted.

READ MORE: Tunnel Vision: Fort Bonfacio War Tunnel Restoration

This is where Digiscript comes in. “Through 3D laser scanning, we will be able to come up with an excavation record and historical archive of the tunnel. It will be easier to analyse the tunnel network holistically and understand its functions during the war. We will be able to come up with surface deformation maps and section profiles along the tunnel alignment, which will help engineers analyse the integrity of the tunnel, and we can accurately compute the volumes of each chamber to determine how it can be used for the musuem,” explains Conrad Alampay, president of Digiscript, which invested in the technology five years ago and has since developed processes unique to the company.

Alampay explains further: “By scanning the tunnel network, we can precisely locate what structures or buildings sit directly on top of the tunnel. This will be useful for future planning, construction, excavation and drilling. This is particularly critical for new construction and avoiding hazards such as drilling through utility lines or into the existing tunnel. We can also accurately determine the exact depth of the tunnel relative to street level.”

[full_width padding=”0 0 40px 0″]

Modern Buildings

The technology has proven effective in scanning complex mechanical, electrical, piping, and structure environments, in order to prepare plans for major renovations and retrofits. In order to properly design these improvements, architects and engineers need as-built records as reference and basis for their design. Although required, many old buildings no longer maintain or have a record of their as-built/blueprints. Or if they do, they are outdated or inaccurate.

Using accurate baseline data is critical and will greatly reduce change orders, wastage and rework. It is a common occurrence for major piping systems to clash/coincide with structural beams. The usual recourse is for the original pipe to be rerouted, which results in increased time, cost and resources.

Another application for 3D scanning, says Alampay, is asset or facilities management: “It can serve as a central visual database that links multiple sources of information digitally to the actual physical structure. For example, after scanning a building, attributes such as material composition, maintenance records, as-built drawings and equipment manuals can be linked to the 3D digital model.”

The 3D scanning technology has proven effective in scanning complex mechanical, electrical, piping and structure environments, in order to prepare plans for major renovations and retrofits.

Archeological sites

Here’s a more esoteric example of how one might use the technology: 3D scanning could be used to digitally archive the country’s oldest known artwork, the ancient petroglyphs in Angono, Rizal—127 human and animal figures engraved on cave walls dating back to 3000 BC.

The site is currently under the protection of and managed by the National Museum of the Philippines. After completion of the 3D scanning, the Museum has been considering producing precise molds and replicas of the engravings that can be 3D printed and used as exhibit pieces for a more interactive experience of the site. Visitors barred from getting within arm’s length of the rock walls would now be able to touch and hold the replicas.

Forensics

The technology is useful for forensic investigation as well, since it can rapidly capture the scene of the crime and preserve its integrity for analysis and investigation. Alampay, who is a consultant to the National Bureau of Investigation, has been called numerous times to provide his expertise in various criminal cases.

He explains: “Usually, crime scenes are cleared almost immediately after the initial investigation. If the scene is scanned, it can be digitally preserved and will be useful in the event that new evidence emerges. Investigators can virtually revisit the scene of the crime and place new evidence in context of that scene.” Alampay adds: “3D data is used in court hearings and presentation of evidence. It can also be used to analyse bullet trajectories and angles after a shootout, and was in fact used during the investigation of the Rizal Park hostage-taking incident in 2010,” referring to the event when 25 people, mostly tourists from Hong Kong, were held hostage by a disgruntled PNP officer.

The technology is useful for forensic investigation as well, since it can rapidly capture the scene of the crime and preserve its integrity for analysis and investigation.

Heritage structures

Ultimately, Digiscript can create an extensive library of crucial information about our heritage buildings, tourist attractions and iconic sites, preserving what is essential in our past. With 3D printing technology, Digiscript can virtually print a complete and accurate replica or scaled miniature of a monument, sculpture, and even unique architectural features like the cornices and capitals on top of churches. Digiscript has done this for the Bonifacio and Rizal Monuments, museums in Taal, and churches in Ilocos Norte and Sur.

“A photograph may mean nothing because it was taken in the present,” says Paulo Canivel, Digiscript Vice President. “But if you go back to that same photograph after a few years, it takes on greater value, because you’ve managed to preserve a moment, which is already gone, if not completely lost.”

Canivel is responsible for the proprietary processes and workflows employed in Digiscript, and is the leading technology expert of High Definition Surveying (HDS) in the Philippines. His vision is to archive all of the country’s heritage structures.

“If we had digital copies of all our heritage buildings, then we can preserve them for future generations and even rebuild them from scratch, should they be destroyed by storms or earthquakes,” says Canivel excitedly.

Click here for more information about Digiscript Philippines, Inc. ![]()

This story first appeared in BluPrint Volume 1, 2015. Edits were made for Bluprint online.

Images courtesy of Digiscript