See a Kalinga Village evolve through the lens of a photojournalist

It was October 1986, and I was on a narrow metal footbridge suspended high above the rushing water of the Chico River. On my back was a pack of heavy photographic equipment—two cameras, 50 plus rolls of film, and multiple lenses. As I gripped the handrails, trying to stay in the center and keep my gaze focused ahead of me, not down, the rickety footbridge swung and tilted wildly with my every step.

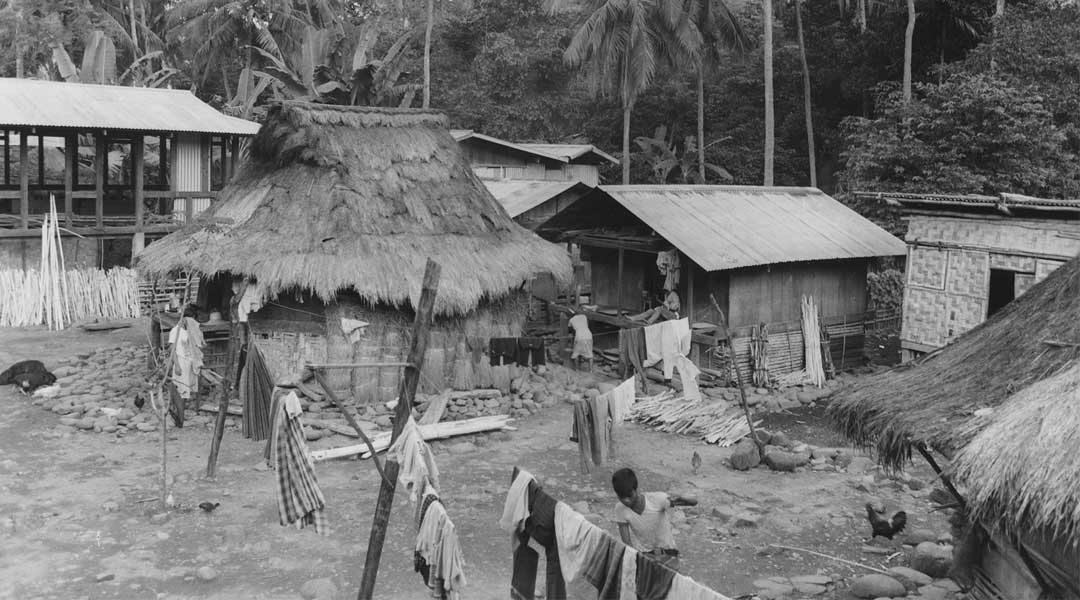

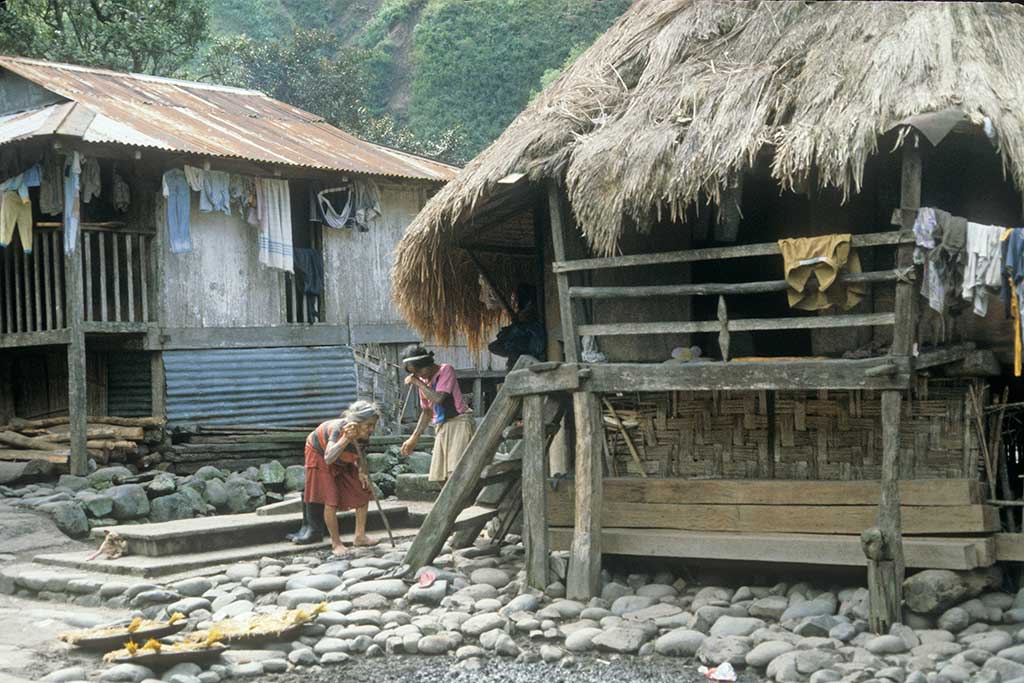

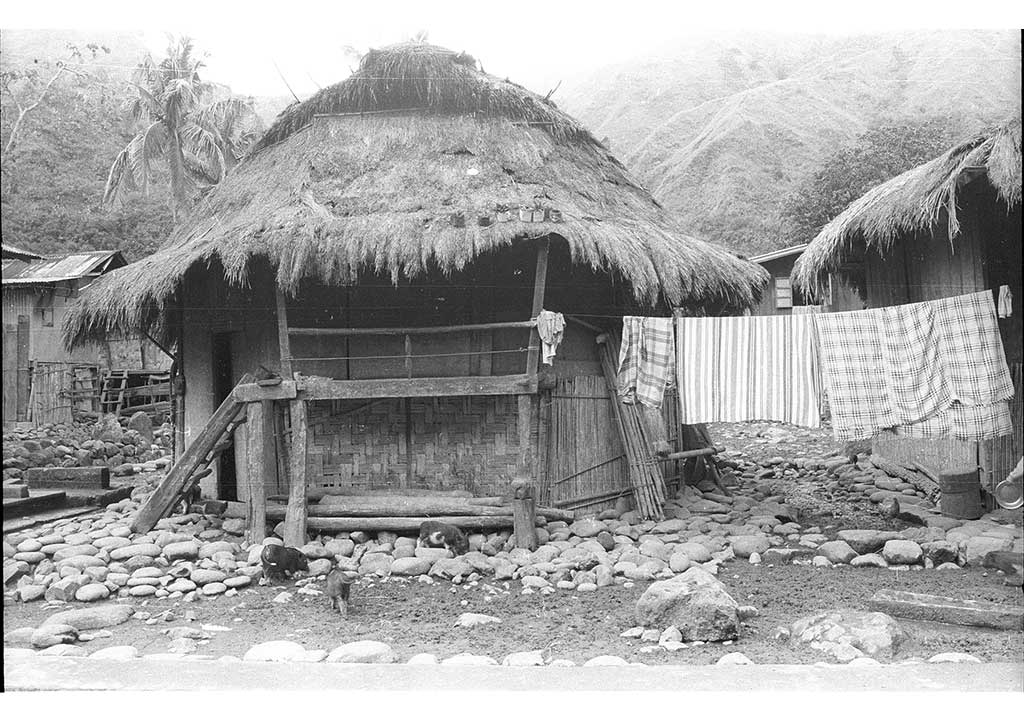

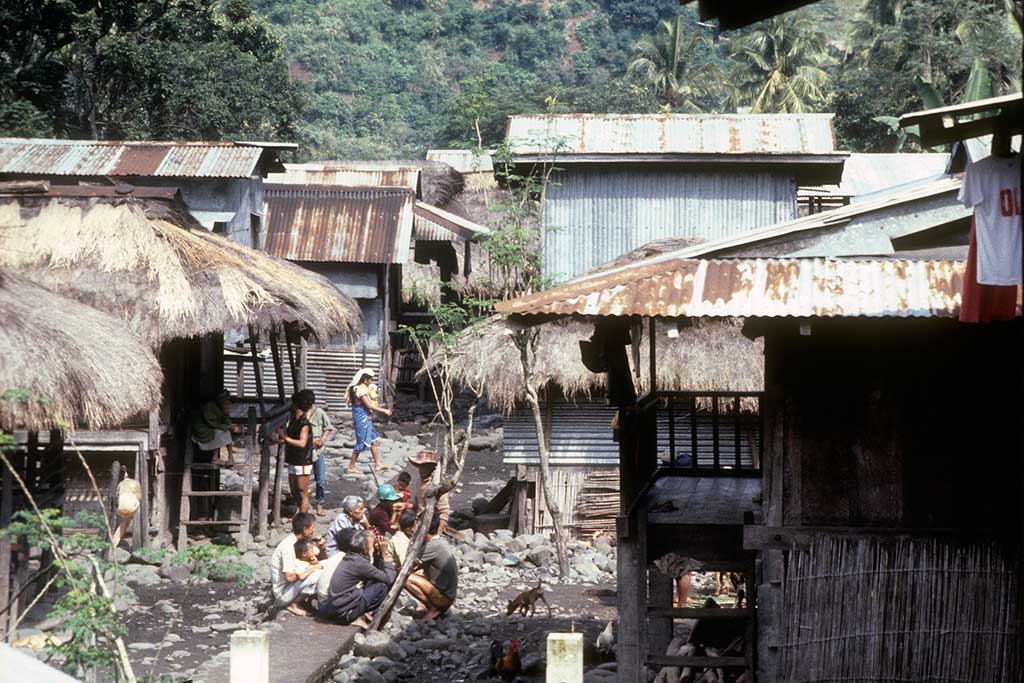

Ahead of me was the Kalinga village of Luplupa, one of several isolated Tinglayan barangays built on a steep mountain slope, strategically placed so that its inhabitants could see their enemies approach. Built in 1915, Luplupa is nestled deep within the hand-carved rice terraces of the Cordillera Mountains, and appeared to be a landscape untouched by modern times. Climbing up and into the village, I saw many octagonal houses perched on stilts, made of wood or flattened woven bamboo, and topped with cogon grass roofs.

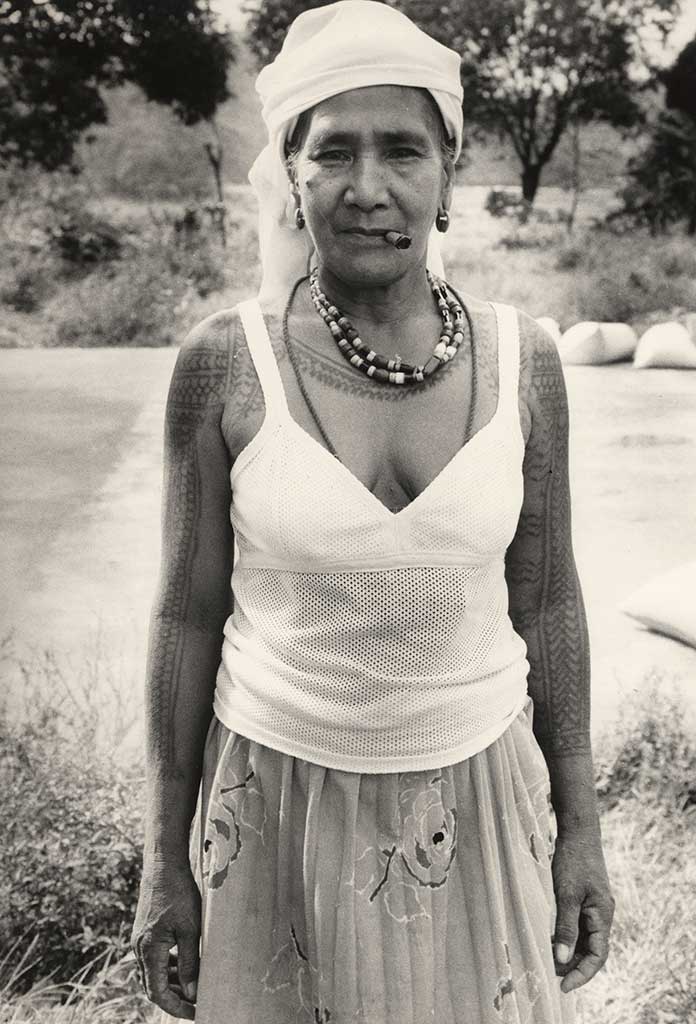

Women with intricately drawn tattoos covering their arms and chests carried pots of dishes and clothing balanced on their heads to wash in the Chico River. Around them, roaming freely, were chickens, dogs, native pigs and a multitude of young children while elders squatted in small groups smoking tobacco. With no toilets, the villagers relied on their pigs to consume any organic waste. What I didn’t realize at that moment, however, was that this village would experience a radical transformation that would entirely restructure the tribal landscape within 25 years.

For centuries, the mountains had served as a rugged natural barrier to military occupation, and the Kalinga warriors had resisted the Spanish army and priests while the lowland Philippines were both colonized and Christianized. Kalinga means ‘cut the head,’ and the name was given to the tribe because of its notoriety for cutting the heads of its enemies as war trophies. Many Kalinga villages remained isolated not only because of their fearsome reputation but for other reasons as well: the region was a base for the guerrilla forces opposing the Marcos dictatorship, suffers mudslides in the rainy season, and at times can only be reached by hiking from village to village along the narrow mud paths on top of the rice terrace walls.

READ MORE: Architectural photographs (or the remains of our buildings)

Fascinated by the story of an ancient indigenous culture, I returned to Kalinga province six years later, in 1993, and witnessed the start of its extraordinary metamorphosis. I had been working in New York City as an architectural historic preservation photographer and photojournalist, and recognized that what remained of Kalinga’s significant vernacular architecture had to be documented before it was irrevocably lost. I returned in 2000, 2002, and finally again in 2013.

During that first visit in 1986 to 1987, while working on a photo-essay for a newsmagazine, I met Virginia “Virgie” Puyoc, who was a Kalinga representative at peace negotiations between the new Cory Aquino government, the Cordillera tribes and the local underground rebel forces. She invited me to visit her village, Luplupa, and we became lifelong friends.

When I returned in 1993, the enormous changes had begun. Virgie had moved from a one-room house on stilts with bamboo floors in rural Luplupa to a newly settled urban village of Bado Dangwa, right outside the state capital of Tabuk, about six hours away. She was now working for the provincial government as an accountant at the Kalinga Special Development Authority, and had begun construction of a concrete, two-story house on land bought by her father in the 1980s, that had been previously used for growing peanuts and kamote.

Back in Luplupa, new construction of larger wood houses with galvanized aluminum roofs was beginning to surround and dwarf the traditional structures.

By my visit in 2000, Virgie’s family compound had expanded. She had built a separate one-story house for herself and her son adjacent to the one I had seen in 1993. Her new house had electricity, bedrooms, a kitchen with a hot plate and sink, and an adjacent water pump and tall concrete water tower. Every morning the family gathered under a big tree between the two houses to drink their locally-grown coffee while her mother, Ina, continued to cook the rice outside because “it tastes better over the wood fire.”

In 2002, Virgie called me with news that the last of the original houses in Luplupa were about to be torn down. I left as soon as I could, and brought with me earlier photos of the village and questions for the elders about the history of each house, including when it had been built, by whom, and how it had been passed down over time.

Eleven years elapsed before I was able to fund my most recent trip in March 2013. Whereas Bando Dangwa had a few houses in 1993, I found that today it has become a densely populated urban landscape filled with people migrating from Luplupa and the neighboring Tinglayan barrios. Villagers have constructed large houses with five or more rooms. On this trip, I had choices of bedrooms, where in my first visits I had stayed with all the unmarried women—the grannies, aunties and teenage girls—who slept close together on the bamboo floor in the same one room in which they cooked and ate their meals.

READ MORE: Architectural photographers we’re now following online (part 1)

Compared to a hut with a grass roof that must be replaced every five years, the new steel-roofed homes require less maintenance and are much more spacious. Instead of having pigs consume the waste, most houses now have indoor plumbing and bathrooms with toilets flushed with buckets of water. The waste, however, now flows directly into the Chico River. The villagers’ main decorative luxury is costly colorful floor, kitchen and wall tiles.

Luplupa’s dramatic development is in part due to funding from a German donor who married a local girl. He pays the school fees for all the children in Luplupa through high school. A variety of Christian missionaries have also set up an extensive network of churches in the last 20 to 30 years, and many of the villagers I talked to have since rejected their pagan roots. Finally, access to television has enlarged their worldview.

READ MORE: Flux and fluidity of Calatrava works photographed by Karchmer

Today, it is acceptable and possible to leave the village to go to college outside the area; some live in cities as far away as Manila, and sometimes even marry outside the tribe. All these changes then further contribute to better jobs and more money to send home to build bigger houses.

READ MORE: The surreal ‘scapes’ of Jay Yao’s drone photography

Virgie feels little nostalgia for the older village houses. “As far as the old houses, baliwala,” she says, “we are not attached to them. Compared to a hut with a grass roof that must be replaced every five years, new metal-roofed homes require less maintenance and are much more spacious and comfortable.” But Virgie still displays a profound connection to her vibrant Kalinga culture—to the language, festivals, music, singing, dancing, foods, cooking, and storytelling. She delights in sharing with me legends and folklore that were told to her as a child.

I showed a group of Kalinga youths my photographs of their village as it was 27 years ago, and taught them to take their own photographs of traditional artifacts still found in the villages. Their pride in their artistic and cultural heritage was evident. They could see that even when tangible things are mostly gone, photographs can provide historic record of the heart and soul of the tribal traditions, and of their ancestors who built and sustained Kalinga culture over many centuries. ![]()

This article first appeared in BluPrint Vol 5 2013. Edits were made for Bluprint online.

Photographed by Trix Rosen

READ MORE: Tips for better architecture photography