What does inclusive street design look like?

Whenever we complain about the traffic, the suggested solutions are always to widen the roads, add flyovers and replace crosswalks with a pedestrian overpass or underpass. And so we have more roads, narrower or no sidewalks, and those silly strips on some roadways local officials pass off as bike lanes. But traffic is not our biggest problem—the hazardous state of our streets is.

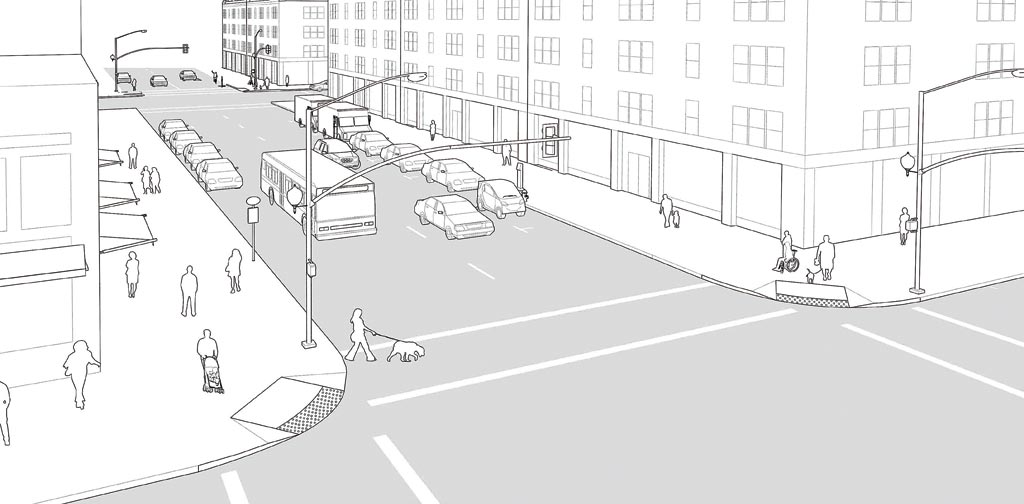

Eighty percent of the population in Metro Manila commutes without a private car. Even those who drive, at some point in the day, have to get around using the sidewalk. Yet our street patterns allot bigger space for cars than pedestrians. It’s obvious in the way we plan long city blocks and expand streets for smoother vehicular flow. The result is not just horrendous traffic jams and pollution, but also a hostile environment for people on foot.

Research group Thinking Machines reported that from 2005 to 2015, there were 57,877 pedestrians injured or killed in Metro Manila, based on data from the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA). That’s 16 pedestrians hurt or killed each day. In 2014 alone, 443 people were killed and 20,899 were injured in road accidents. A huge 44%, almost half of the casualties, were pedestrians—190 killed and over 9,000 injured.

New business districts and mixed-use developments in Metro Manila had the chance to start with a clean slate, set a good example, and reverse the postwar practice of designing for sprawling suburbia. Sadly, these new developments still favored long, wide and impermeable blocks with few crossings so cars can quickly move from point A to point B. This is why people still drive in places like Eastwood and Bonifacio Global City despite the clean, unobstructed sidewalks.

READ MORE: How do we make sure Asia’s megacities are healthy cities?

Even in low-density neighborhoods, street conditions discourage people from walking and biking. In an oppressively hot and humid country where summer temperatures can reach as high as 45° C, and where there’s torrential rain half the year, our streets provide little to no protection from either.

In Ortigas, the streets have only two to four lanes, yet the sidewalks are fenced off and there are no crosswalks at grade. Pedestrians are forced to take the footbridges. Although some footbridges and pedestrian underpasses have elevators or escalators, most are broken and filthy. It is heartbreaking to see the elderly and handicapped struggling to ascend the often steep staircases. If we are to build pedestrian overpasses, let them at least offer dignity to people, with gentler inclination, roofs, and lighting for safety and security at night.

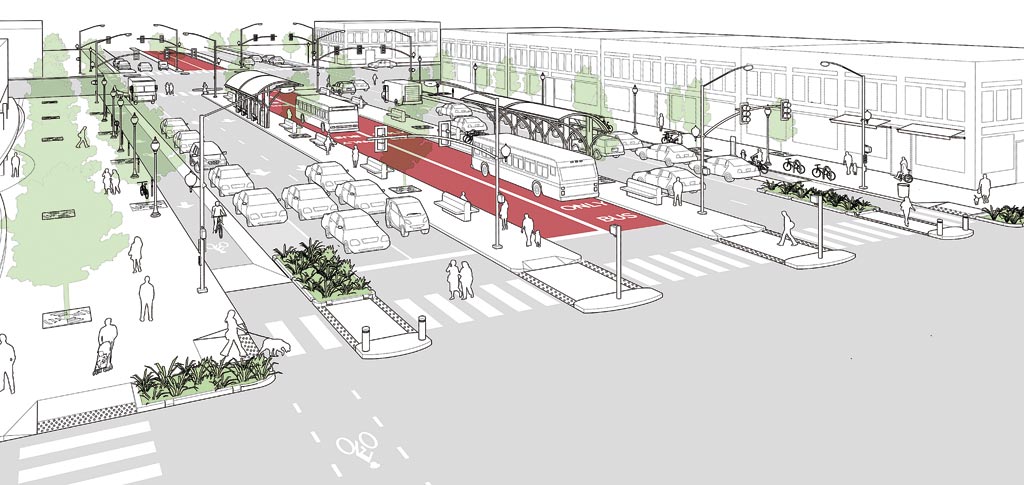

How then do we transform our car-centric city into a walkable one? New York transport commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan advocates immediate, decisive action. In 2009, she transformed Broadway in Times Square from New York’s busiest intersection into a pedestrian plaza overnight. She followed the lead of Curitiba’s mayor Jaime Lerner who, within 72 hours, turned Rua XV de Novembro, a major thoroughfare spanning 15 blocks, into Brazil’s first pedestrian street.

“Culture change takes time, but cities have to move quickly with infrastructure,” Sadik-Khan reasoned. During her term, she oversaw the addition of 400 new bike lanes, 60 new pedestrian plazas, and the largest bike sharing program in the US. She admitted that none of her ideas were new, but the speed of delivery surely was.

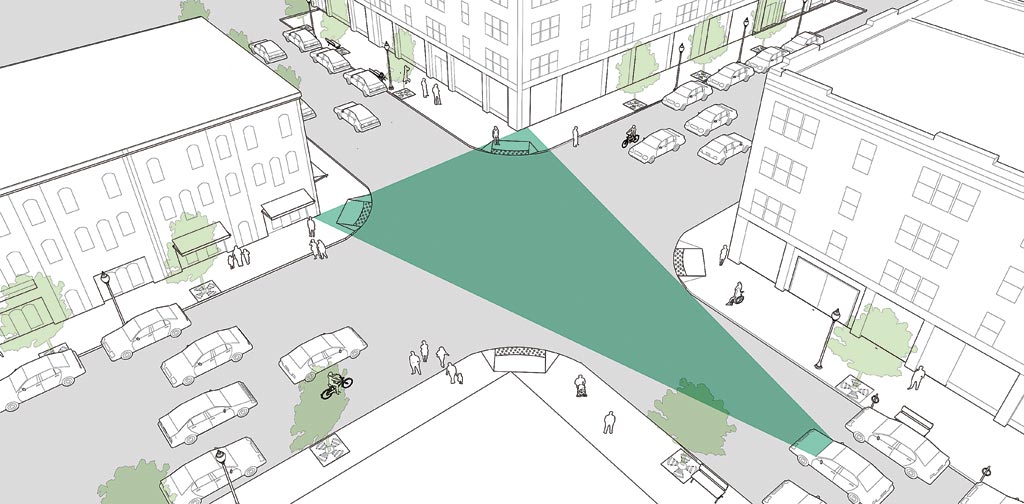

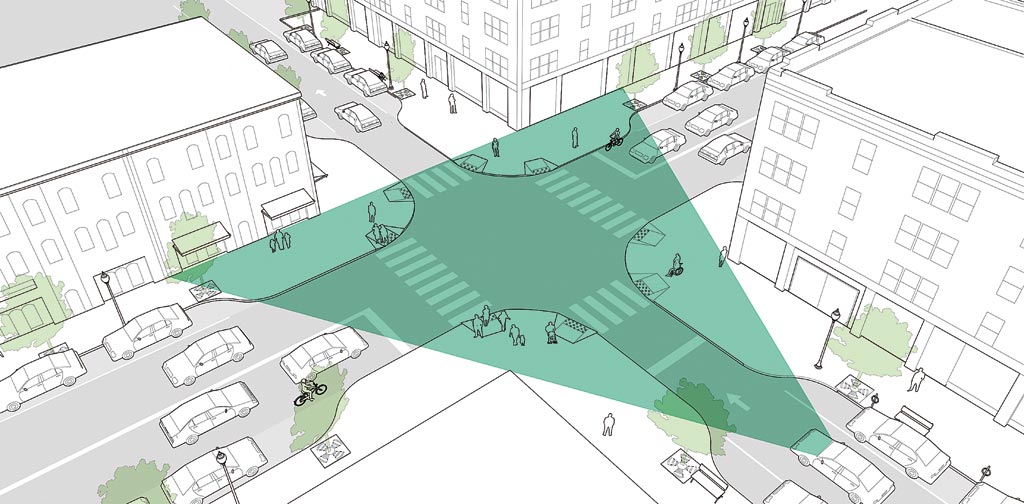

However, in red tape-ridden bureaucratic democracies such as ours, programs like these could be a tough sell. Major projects requiring sustainable funding schemes like raised bikeways, wider sidewalks and traffic calming elements could take five to ten years to complete. The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) recommends a phased, scaled approach to manage public acceptance and get buy-in.

During the annual Firefly Brigade’s Tour of the Fireflies and the National Bicycle Day in Metro Manila, local governments work with national agencies such as the MMDA and national police to block off certain roads for a day to allow the safe passage of bicycles throughout the metro, including long stretches of EDSA. If programs like these could work for a day, we can explore if it will work on a weekend, on a week, and so on. This sets the vision, builds support, and allows the community to experience new street uses for themselves. If they like the experience, they will clamor for new street configurations to be institutionalized.

Both Sadik-Khan and Lerner encountered fierce opposition at the outset. “A lot of people said bike lanes wouldn’t work because we’re not Copenhagen,” recalled Sadik-Khan. In my dealings with stakeholders in the Philippines, the thinking is similar—that we are not Copenhagen or New York. They don’t believe it will work even when presented with case studies of Mexico, Bangkok, and Bogota whose situations before were no different from ours today. They say our culture is different.

Our culture, laws, and social norms may be different but this is no excuse for fidgeting government action. Familiarity breeds indifference. We should be working towards more permanent and long-term solutions to make our streets more humane. Not doing so is just plain lazy. Sadik-Khan said, “It’s a matter of commitment.” For me, it is just a matter of good governance and common sense. ![]()

This article first appeared in BluPrint Vol 2 2016. Edits were made for Bluprint.ph.