Modernist Avatars: National Artist Jeremias “Jerry” Elizalde Navarro

An uncompromising idealist to the modernist cause, Jeremias “Jerry” Elizalde Navarro (1924-1999) thought nothing of changing his painting style constantly—from minimalism to abstract expressionism, cubism, pointillism, assemblage, and in his final years, a melodic figurative style that highlighted the female form and the Asian heritage that he closely aligned himself with since the 80s.

He once told me that “somebody went inside the Met Museum during my 1996 retrospective, and he said ‘Gee, I thought there were twelve artists who did the whole thing.’ To me, a real artist shoots in so many directions, and he shouldn’t give a hoot about what people will say. I don’t believe in style. To me, it’s a point of submission. Look at Joya. He died painting the same things…I wrote to Malang and told him: ‘I don’t want to see you die painting all those women vendors and flowers!’ I think he got sore at me.”

More importantly than stylistic consistency, therefore, Jerry Navarro believed that the inherent creativity of the human being enabled him to be independent of the demands of the art market and the potentially stifling conditions of patronage once that market demand has been achieved. It is this calculated rejection of the market, and his privileging of artistic freedom, that resulted in so many different styles. For as Jerry Navarro pointed out, artistry is not the result of financial or social success, but rather the ability to forge beyond consensus and compromise in order to be truly unique and autonomous. This was why style was irrelevant to him.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Filipino artist Roberto Robles’ songs of transcience

This idea is integral to the understanding of Modernism as a “stylish” concern, since by “modern style” we actually refer to an aesthetic feeling rooted in the modern condition: the alienation of the individual through rote work and repetitious, mechanical labor, for example; or the dissolution of nature into man-made, and therefore abstract, forms. At the same time, however, we need to situate Jerry Navarro’s idea of Modernist freedom within the Asian sensibility that he is a pioneer of in the Philippines, one whose Modernist transformations can be likened to a Buddhist avatar undergoing constant reincarnation.

His posthumous National Artist Award, given six months after his death to bone cancer, describes his contributions to Philippine Art as an expression of “a profound vision and sometimes to simply play, thereby expanding the frontiers of his discipline…His abstracts are a fusion of geometric shapes and spontaneous strokes, while his figures recall the joy and exuberance of culture and art.”

READ MORE: Sophisticated Folk: The Genre Works of National Artist Vicente Manansala

Jerry Navarro’s modernist vision was primarily shaped by his fine arts education at the University of Santo Tomas after World War II, where Carlos “Botong” Francisco was a major influence on his early painting and design style—and where he would meet his first wife, sculptor Virginia Ty.

As a Ramon Roces scholar, Jerry Navarro worked as an apprentice illustrator in the Roces publishing empire during the late 40s alongside Vicente Manansala and Romeo Tabuena, and who would in turn influence his stylistic disposition towards Modernist cubism and distorted figurative paintings that would later be known as Neo-Realist. It was also Jerry Navarro’s part-time work as a columnist at the UST publication The Varsitarian that flexed his critical mindset as a future art critic. Later, Navarro would be instrumental in developing the advertising program at UST as a separate course from painting as a young instructor, while doing his bread-and-butter job as an illustrator—then later, as an art director—of the pioneering Filipino-owned advertising firm Ace Advertising Agency (now Ace Saatchi & Saatchi).

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Abstracting Nature: Jose T. Joya and his abstract expressionism

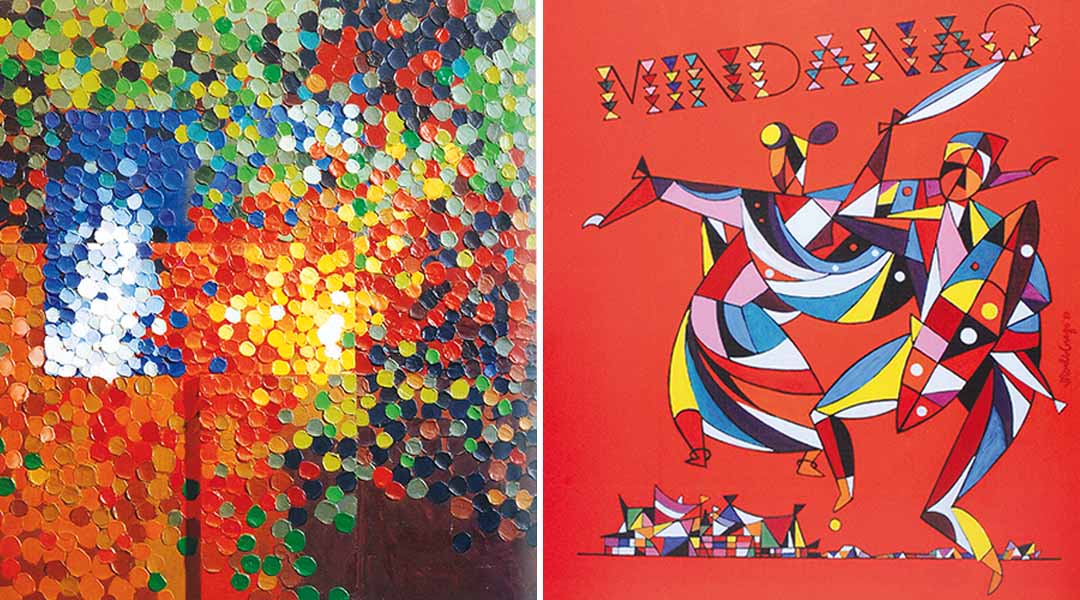

Winning his first professional award via the 1952 AAP Annual Poster Competition for Mindanao, Jerry Navarro traveled to the US under an Ace Advertising grant to study at the Art Student’s League of New York and visit the great museums like the Metropolitan, the MoMA, and the Guggenheim. There, he would see the canvases of Wassily Kandinsky, which would forever alter his perception about modernism through its combination of intellectually, abstraction, and the feeling for universal harmony.

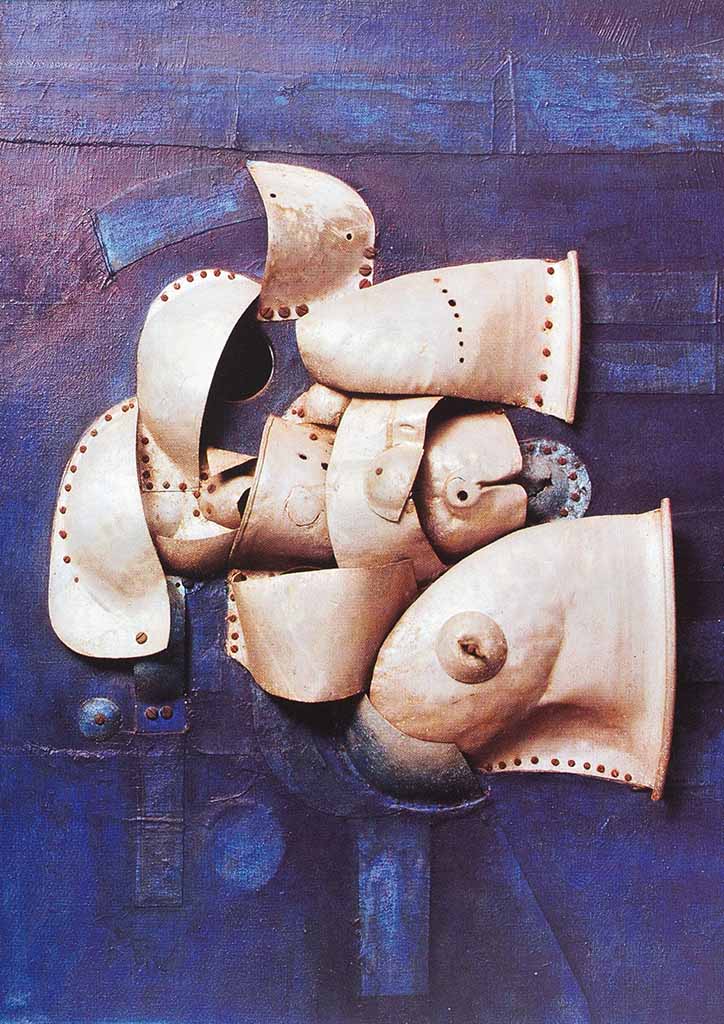

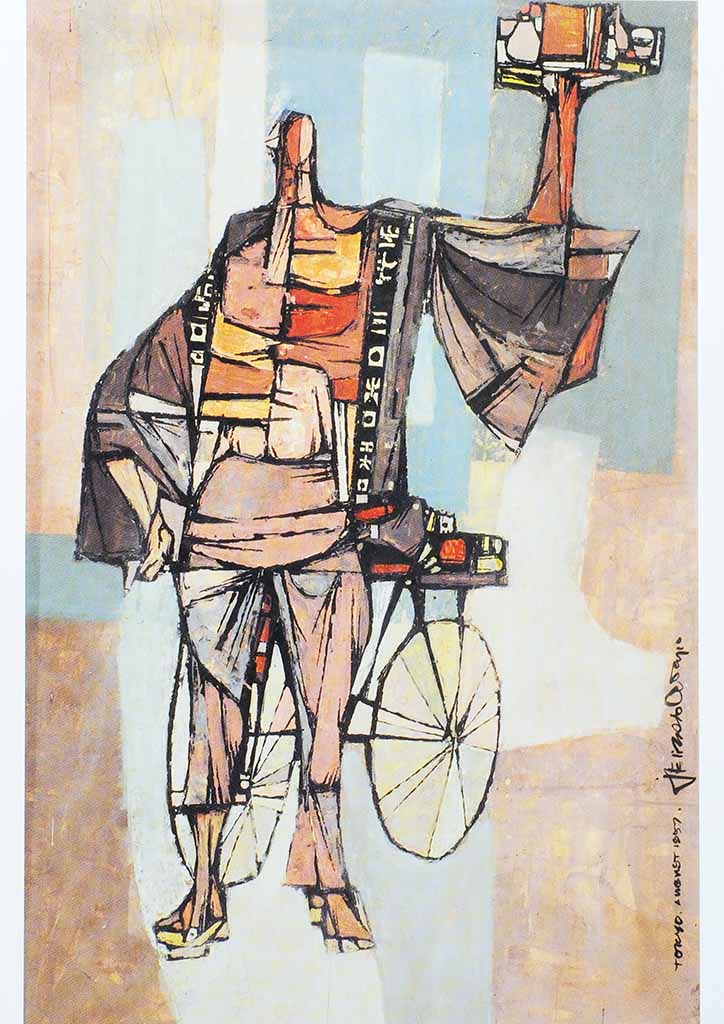

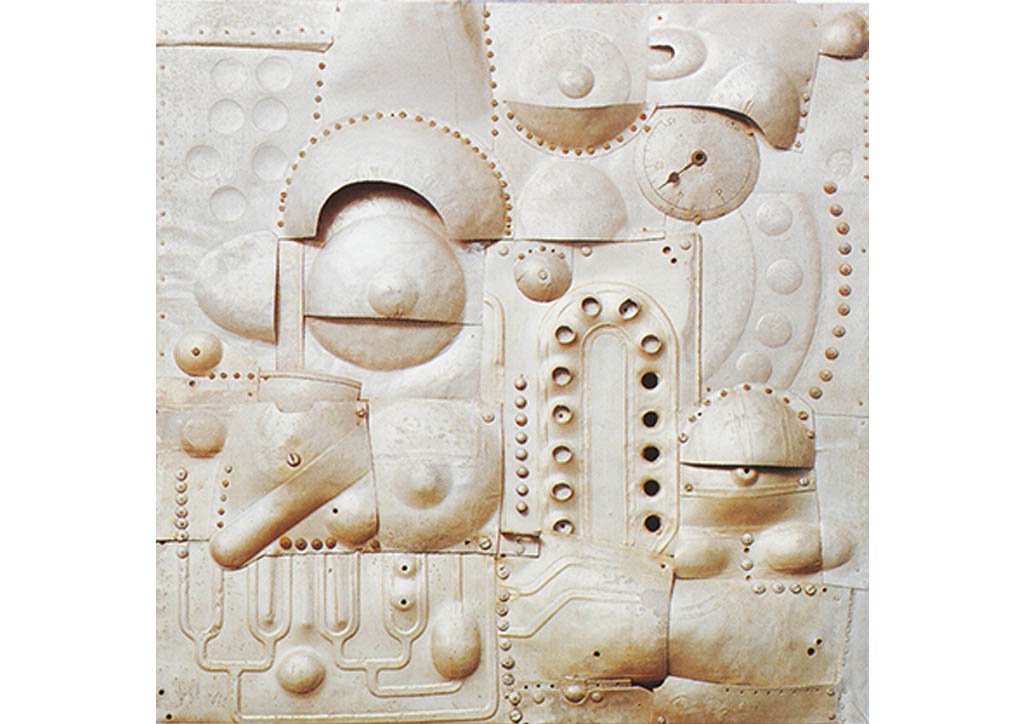

A committed abstractionist upon his return, Jerry Navarro would paint using a fragmentary Cubist rendition of human figures and still life like his UST friend Hugo Yonzon, or his mentor Manansala; or go into abstract Constructivist assemblages of wood and metal. A trip to Japan in 1957 also gave Navarro a decidedly Asian orientation to his modernist works by using geometric planes and sumi-e-like strokes on long rectangular pieces, or circle-in-square formats done in metallic colors like silver, electric blue, and gold. This can be seen in works like The Blue and Silver Machine (1953) or The Silver Golden Machine (1957) whose erotic mechanical shapes vaguely recall the Dadaist works of Marcel Duchamp or Francis Picabia.

READ MORE: Fusing Old and New: National Artist Benedicto “BenCab” Cabrera

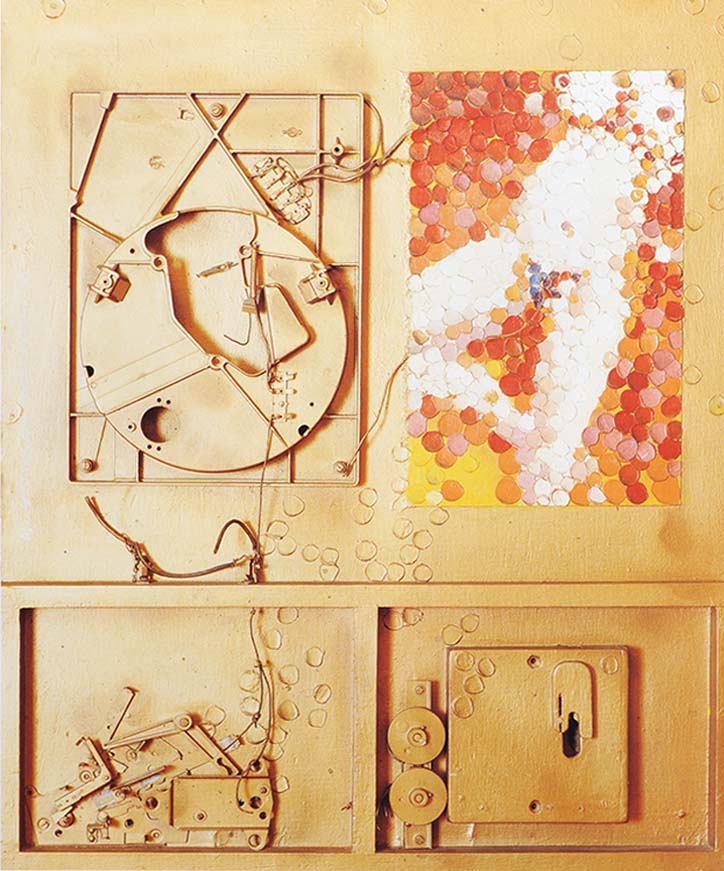

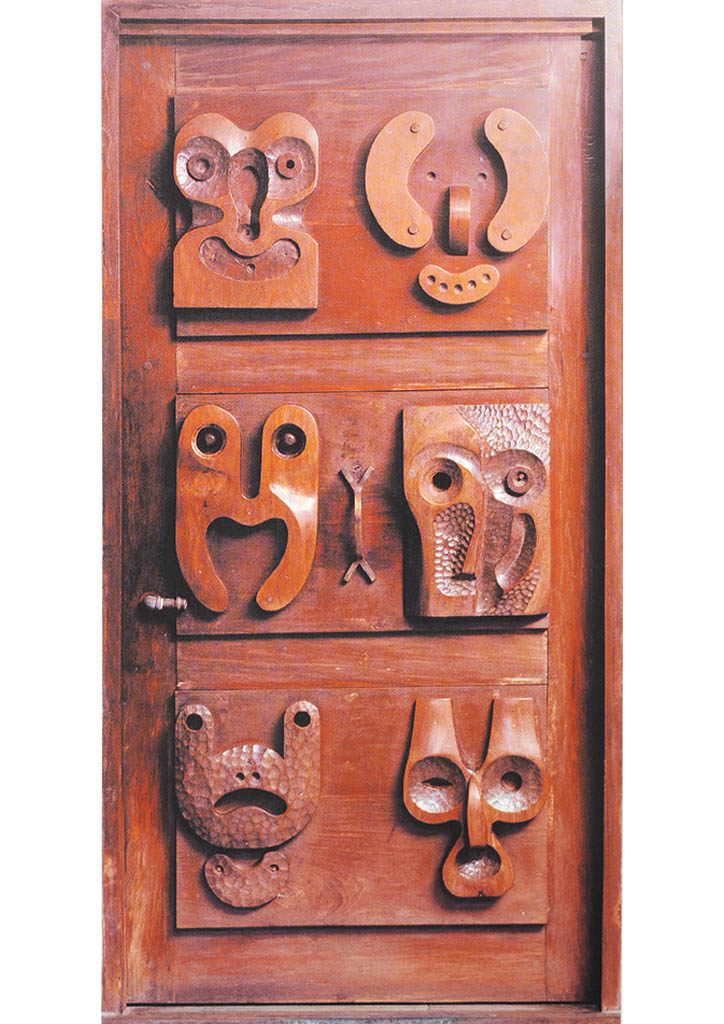

Jerry Navarro’s works in the mid-late 60s would be considered the “classical period” of his Modernist works. In materials like hardwood and aluminum, or colored plexiglass sheets clamped into stainless steel frames, Jerry Navarro’s assemblages were often of portraits that also served as masks that presented a face to the world while hiding the true human emotion within. Freestanding sculptures like Man Woman (1960) or Grand Prix: Homage to Dodjie Laurel (1969) tackled themes like mythology or the frailty of man who attempted to run like gods.

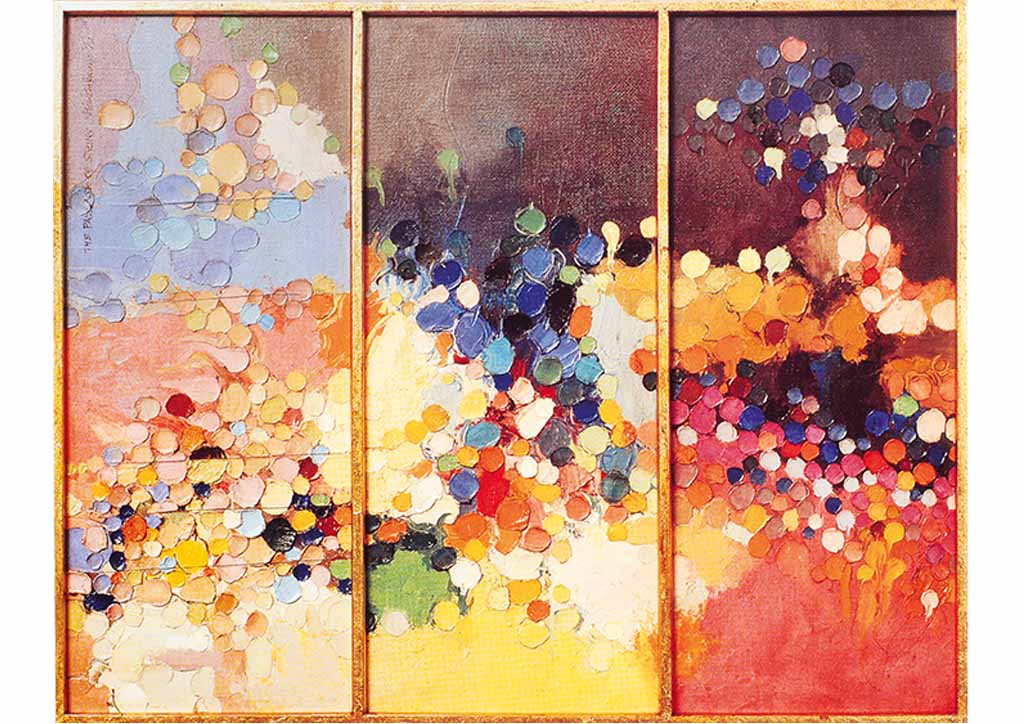

On the other hand, the use of a heavily pointillist technique in painting, done as an abstraction by smearing almost perfectly round shapes using oil tubes, also marks his 60s works like Kyoto Sounds, and whose brilliant coloration is said to characterize his Visayan heritage for color, one which would reappear again in the 80s and 90s.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Dissecting the stained glass windows at the Manila Cathedral

His separation from Virginia Ty and elopement to Australia with Emma Villanueva in the late 60s would provide cathartic realization that would end Jerry Navarro’s dependence on the advertising industry for work, and set him off on the path to pure artistry. Jerry Navarro’s warm relationship with Emma also allowed a literal blooming of his colors from the 70s onward, resulting in brilliant color combinations like the gold-red-white combination in the assemblage All Systems Go! (1970); or the richly melodic triptych panel in yellows, reds, and blues, titled The Passage of Spring (1972). This would be heightened in Navarro’s regular visits to Bali, Indonesia, from 1987 to 1997 as a resident artist to Cornelius Choy at Ubud. There, he would paint the tropical environment, sample the rich Hindu cultural heritage of its gloriously-attired dancers, and depict the female nude in the natural bounty of Bali’s forested streams.

It would also be in Bali that Jerry Navarro would tap into the deep vein of his last series of colorful abstracts. Encompassing large swaths of color with exuberant swirls, zings, and dashes of brilliant lines, Jerry Navarro’s Bali series brings his work to a brilliant finish with a return to the early stages of his modernist career, when the cubistic, red background poster Mindanao launched his career to modernist greatness, and where he found himself to be a true Asian and a committed Modernist.

This first appeared in BluPrint Volume 5 2011. Edits were made for BluPrint online.