As the built environment evolves, the role of the architect demands reconsideration. For Jose Siao Ling, Co-Founder and Principal Architect of Jose Siao Ling & Associates (JSLA Architects), the role extends far beyond being a licensed professional who designs and oversees construction. By championing ethical practice, ISO-certified systems, and mentorship-driven leadership, he built a firm […]

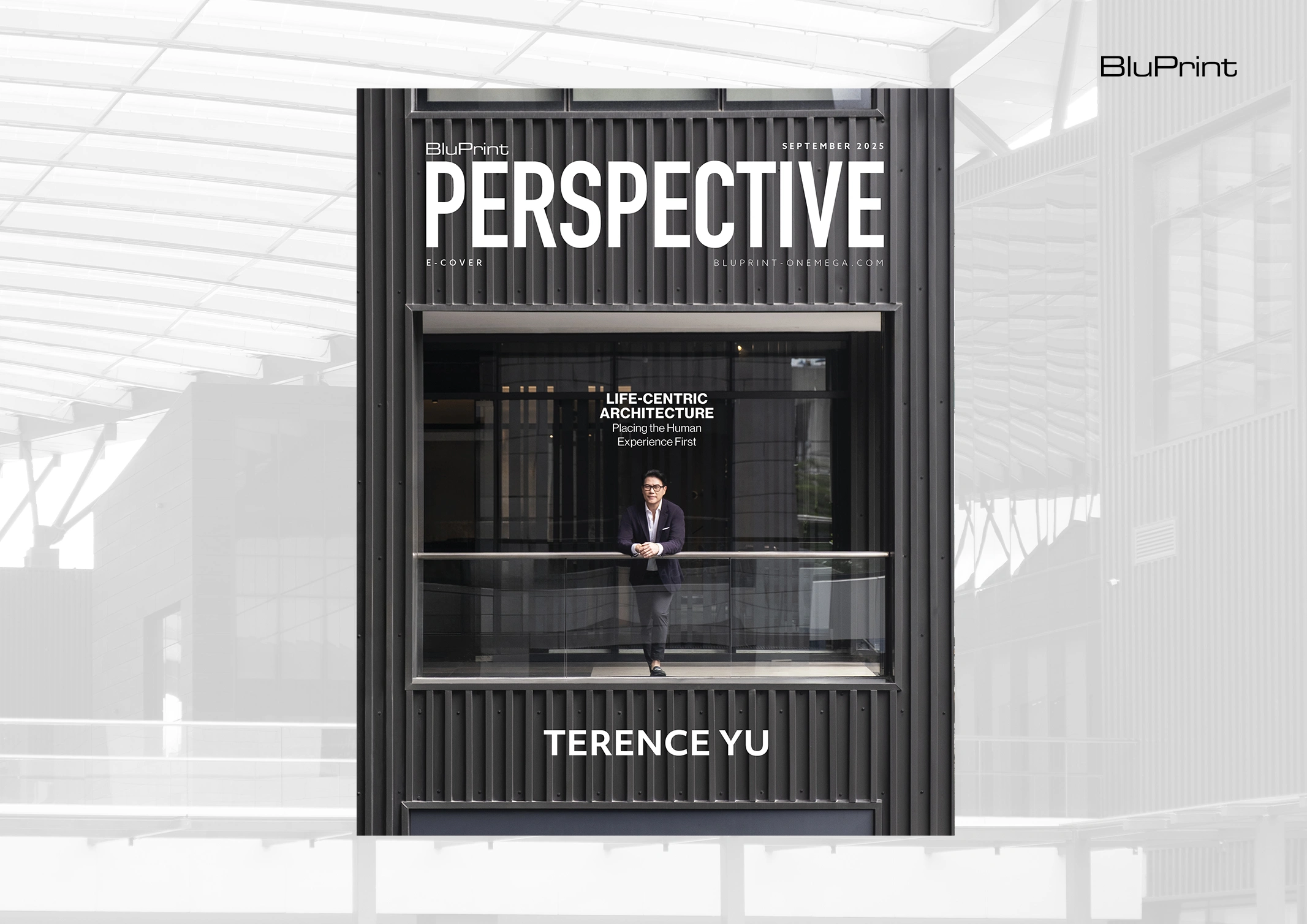

Life-Centric Architecture: Terence Yu Places the Human Experience First

At its core, architecture has always been about the human experience. While this fundamental purpose can sometimes be overlooked amid the complexities of modern life, a renewed focus on human-first principles is taking hold. This deliberate approach is articulated in the philosophy of Life-Centric Architecture, a mandate championed and put into practice by Terence Yu , President and CEO of globally-ranked architecture firm, Visionarch.

The philosophy begins with a foundational question: how can our built environments actively contribute to a better quality of life? The goal is to move beyond mere function and aesthetics to consciously craft spaces that support the intricate balance of modern living—our social connections, professional ambitions, and personal well-being.

Codifying a Better Quality of Life

For Yu and his team, it is the essential task of modern architecture to provide a pragmatic, empathetic response to the complexities of urban living in the Philippines. This question has become the central algorithm for his practice. It has guided Visionarch in completing over 1000 projects, positioning Yu as a pivotal figure in shaping the nation’s future skylines.

The firm’s guiding philosophy of Life-Centric Architecture is a direct response to the aspirations of a nation in rapid transition. This human-first approach is the bedrock of its success and local impact—propelling the firm to 56th in the World Architecture 100—and proves that the most enduring designs are created for the people who inhabit them.

Yu and his team conceived the philosophy during an early foray into architect-led development in Bonifacio Global City in the early 2000s. Facing the challenge of developing seven condominium towers, they sought to understand the fundamental drivers of the market. “This was a time when we were kind of adventurous with our practice,” Yu recounts. “We did an informal survey. We wanted to understand the people, what makes them want to buy condominiums. Is it design? Is it the location?”

The results were revelatory; mainly that the primary motivation was not aesthetic preference or even location, but something far more profound. “What we learned is that people just aspire to live better lives,” he states. “When they buy condominiums, even though it’s expensive, it’s an aspirational purchase. They want to improve their life condition.” This critical insight reframed Yu’s perspective. “Architecture is being taught as form versus function, but what we’re learning is people want better life conditions.”

The Dimensions of Human Experience

Moving beyond the physical and into the experiential, Visionarch defined “better life conditions” as a deliberate balance between key dimensions of human experience: social, family, and work life, alongside opportunities for learning, exploration, and spiritual well-being.

This multi-dimensional approach considers the whole person, leading to the design of spaces that actively foster social connections, support work fulfillment, and promote wellness through biophilic design. It also incorporates spaces for play and leisure, quiet areas for mental respite, and a strong consciousness for environmental sustainability.

“When we’re able to incorporate a lot of those,” Yu says, “then this makes it more life-centric for people.” And by prioritizing human experience over monumentalism, it gives rise to spaces that are inclusive, health-promoting, and truly meaningful.

The Architect’s Crucible

Architecture is the Yu family’s lingua franca. Terence grew up mentored by the formidable presence of his father, Gilbert Yu, a prominent figure through the 70s, 80s, and 90s. The elder Yu’s life story is a testament to relentless ambition, captured in his book, The Life and Adventures of Gilbert Yu, which chronicles his incredible journey from working as a gasoline boy to becoming one of the country’s renowned architects.

“He was my inspiration to take up architecture,” Yu shares, and that legacy of perseverance and professional excellence was a powerful inheritance. “My uncle is also an architect, and his son is also an architect,” Yu adds. “So they say architecture runs deep in the blood. I guess that’s true.” This environment was his crucible, shaping an innate understanding of the profession’s demands and its potential for profound impact.

At a young age, he took the helm of his father’s firm, G&W Architects, leading its transition into second-generation leadership. For years, he managed the practice, absorbing the invaluable lessons of running a firm and delivering major projects. This period was his apprenticeship in leadership, a time of learning the business from the inside out.

“When I figured out what type of practice I wanted to do, that’s when I established Visionarch,” he explains. In 2012, Yu founded his own firm. It was a deliberate, decisive move to build an organization from the ground up, based on a new, more empathetic model of architectural practice. Today, Visionarch is a powerhouse of nearly 200 dedicated architects and specialists, a clear reflection of Yu’s focused leadership and the compelling power of his central idea.

The Urban Laboratory

But a philosophy is only as powerful as its application. For Terence Yu, the bustling, often chaotic cities of the Philippines are the ultimate laboratory for his life-centric principles. His work focuses on tackling the nation’s most pressing urban challenges with large-scale, strategic architectural interventions.

The Transit-Oriented Imperative

Yu is unflinchingly honest about the realities of urban life in the country. “The Philippines is a great place to live, but we have two problems,” he states plainly. “One is congestion, and one is pollution.” While he believes electric vehicles may eventually solve the pollution issue, “the congestion, I think, is a long-term problem, because our infrastructure is developing quite slow.”

This is where Visionarch’s specialization as an ASEAN Architect in transit-oriented development (TOD) becomes critical. Rather than waiting for infrastructure to catch up, the firm’s designs actively mitigate its shortfalls. Landmark projects like One Ayala, the North Triangle Transport Terminal, and the Taguig Integrated Terminal Exchange are exemplars of this strategy as fully integrated mixed-use hubs.

The goal is to radically transform the commuting experience. “A trend right now is to incorporate the different transport modes into shopping malls or big nodes so that people can be in a comfortable environment,” he explains. This shift elevates a daily necessity from a point of stress to one of comfort and convenience.

“Rather than a commuting experience, which is a utilitarian experience, it becomes more of a leisure and shopping mall experience. So your everyday experience will be more pleasant,” he asserts. One Ayala, which vied for Best Future Infrastructure project at the 2017 World Architecture Festival, stands as the largest Philippine project to ever compete on that global stage.

The Rise of the Self-Contained Community

The lag in public infrastructure has given rise to another architectural solution that aligns perfectly with the life-centric model: the self-contained township. “Even though we do nice private developments, when you go outside, the infrastructure is kind of lagging a little bit,” Yu observes. This disconnect has spurred developers to think bigger.

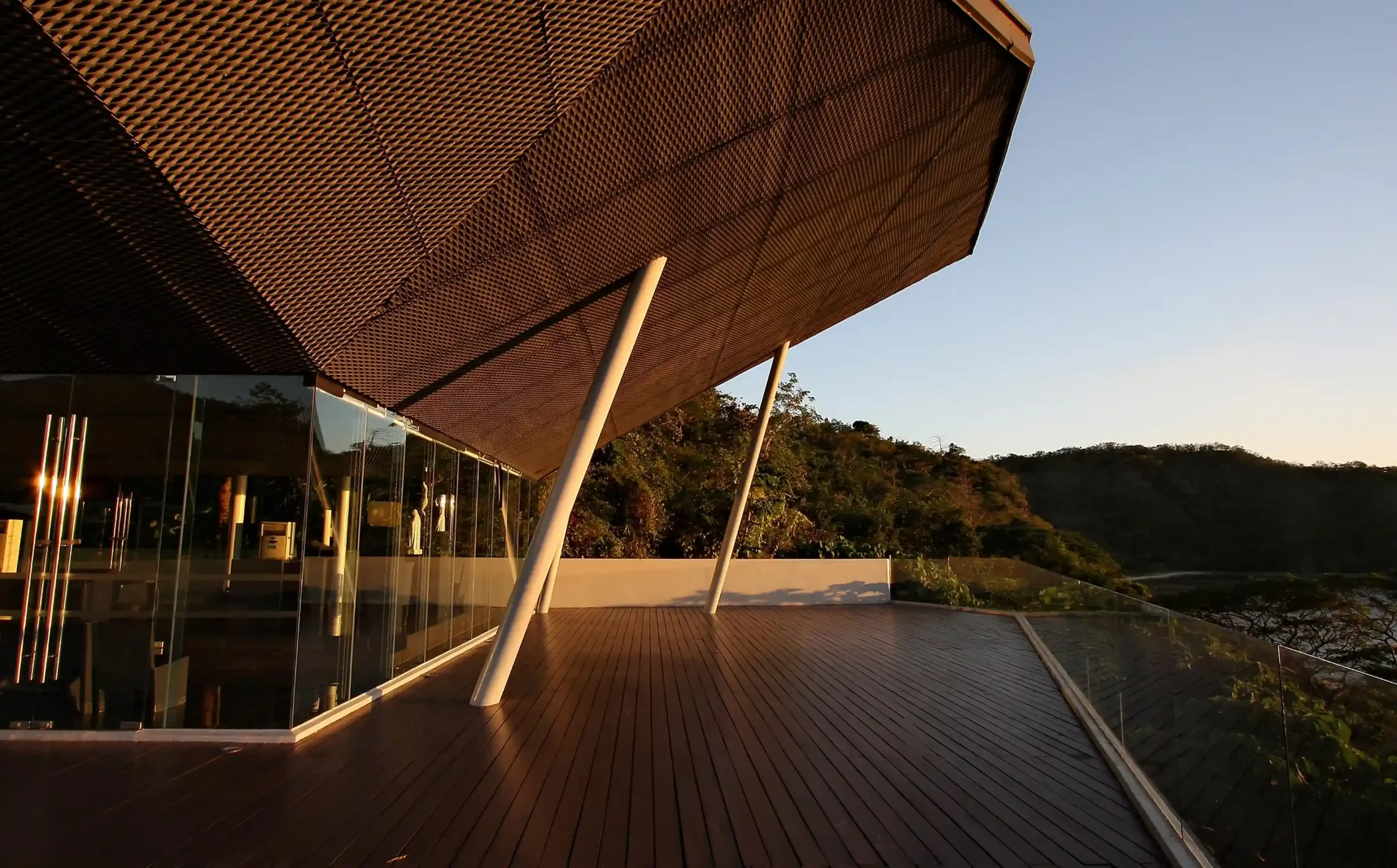

A portmanteau of parke and kalye, Parqal redefines the commercial street for the tropics. Its iconic canopy provides a climate-protected public realm, fostering walkability and spontaneous community interaction in the space below. Photos courtesy of Visionarch.

“Developers are getting bigger parcels… [with this], you can create wider roads… create a nicer mix between office buildings and residential buildings, and malls so that people can stay in place… [Now] they won’t have to endure the two, three-hour traffic congestion every day.”

This approach aligns with the globally recognized concept of the “15-minute city,” an urban planning model popularized by Professor Carlos Moreno. The goal is to create walkable, self-sufficient neighborhoods where residents can access all their essential needs—work, commerce, education, and leisure—within a short walk or bike ride from their homes.

This is Life-Centric Architecture at the macro scale: crafting entire communities where the delicate balance of life, work, and play is achieved in a well-designed, human-centric environment.

The Digital Scaffolding: Technology as a Creative Partner

Executing such complex, large-scale, and deeply considered projects would be impossible without a mastery of cutting-edge technology. Visionarch was an early adopter of digital workflows, leveraging a sophisticated tech stack not just for efficiency, but as a genuine partner in the creative and collaborative process.

Yu frames the role of Artificial Intelligence in design not as a replacement for the architect, but as a new tool that augments the creative mind. “AI is a very, very interesting technology, because for the first time in architecture history, we’re getting tools that help us with the creative aspect,” he emphasizes. He draws a clear line between past and present technologies: “BIM [Building Information Modeling], CAD, and other software help us with drafting, help us with presentation. But the creative side usually just is in the minds of the architects.”

AI changes this dynamic entirely. “With AI, it helps us to generate new ideas, and it helps us with the creative process,” he continues. The primary benefit is rapid iteration, allowing the team to explore a vast array of possibilities that would be manually prohibitive. “It allows us to do numerous different possibilities and then choose from them,” a process that ultimately leads to more refined and innovative outcomes for the client.

De-risking Complexity with Building Information Modeling (BIM)

For collaboration on massive projects, BIM serves as the firm’s operational backbone. Yu eloquently describes its core strength: “One of the strengths of BIM is to create a digital twin. Essentially, before the building is completed, you’re creating a digital version of it in the computer wherein you can collaborate on all the engineering aspects.”

This digital rehearsal is invaluable. It makes the entire process more transparent and proactive, catching potential conflicts and issues long before they become costly problems on-site. “All the potential problems, you see it before you build it,” Yu states. This technological foresight is what enables Visionarch to confidently deliver complex, integrated developments like One Ayala on schedule and to the highest standard.

Cultivating a Profession and a Nation

Terence Yu’s influence now extends far beyond the walls of his firm. As the current President of the Philippine Institute of Architects (PIA), the nation’s oldest and most venerable architectural institution, he has taken on the role of a steward for the entire profession.

His leadership is characterized by a deep reverence for the past and an urgent focus on the future. “What I like about PIA is that it’s composed of the pillars in Philippine architecture,” he says. “We want to respect that legacy.”

To that end, he is championing an innovative advocacy project: a rolling exhibit designed to educate municipalities and cities on the pivotal role architects play in their development. He supports this by noting with pride that in key business districts like Makati and BGC, the “majority of the buildings are done by PIA members.”

Equally important to him is mentorship and knowledge transfer. His work as an educator, teaching advanced design courses at the University of Santo Tomas, and his internal role at Visionarch—“to inculcate and train and teach our different team members of the ideals of Visionarch”—are part of a larger mission. “We also want to transfer our learnings to the younger generations, because we want them to learn their value that they contribute to our country’s development,” he asserts.

This forward-looking perspective fuels his optimism. He sees a bright future for architecture in the Philippines, intrinsically tied to the nation’s economic trajectory. “There’s no choice—government has to invest in the infrastructure,” he predicts. When that happens, architecture will be central to forging a new national identity. “If it is done properly, I think it gives a sense of pride to the people,” Yu concludes. “If you create social and community buildings that are nice and renowned, this gives the people a sense of pride that they’re developing, they’re improving. And so I think architecture will play a big role in that.”

It is this profound belief in architecture’s power to uplift, solve, and inspire that defines Terence Yu’s career. He is a second-generation architect who honored his legacy by daring to build his own. Through a deeply humanistic philosophy, enabled by technology and applied with strategic thinking, he is not just constructing buildings. He is embedding a better quality of life into the blueprint of a nation.

Read more: One Ayala: An Inclusive Transport Hub Along EDSA

Photographer: Ed Simon

Hair and Make Up: Cats del Rosario

Sittings Editor: Geewel Fuster

Managing Editor: Chad Rialp

Shoot Coordinator: Mae Talaid