Filipino artist Roberto Robles’ songs of transcience

Roberto Marcelo A. Robles (b.1957) was profoundly altered by his experience of studying and living in Japan for four years. He combines a fascination for conceptual mind games, social commentary, and an edified view of the past with a restraint that is painstakingly executed on high-quality materials like Carrara marble, granite, and hardwood. In his most recent ‘sculptural environment’ work titled Saluysoy (2010), Robles focuses on the tension between structural symmetry and lyrical treatment of surface elements. Gouges and abraded surfaces form what looks like hard water stains on the otherwise smooth surfaces of granite, while the rust-sealed finish of vertical blocks of steel evokes both strength and decay.

This formal sense of balance can be located in Robles’s rigorous inculcation of Modernist aesthetics in his collegiate and graduate education. The sense of thematic lyricism, however, can be traced back to his childhood in a Batangas farm, where a gushing spring (called saluysoy in southern Tagalog) was a constant source not only of sustenance to animals and people but also of childhood wonder and play for the younger Robles.

During the early 1980s, the Fine Arts graduate from the University of the East was focused on assemblage reliefs of boxed frames that explored the conceptual relationship between memory, social ferment, and surreal imagery.

Exemplified by his 1984 breakout pieces, Box 62584: Awit ng Manggagawa, Sigaw ng Palaka, and Kahong Pula Para sa Palakang Kokak, these assemblages call to mind the pioneering boxed assemblages of American artist Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) whose works, inspired by Constructivist and Surrealist art from Europe, and tinged with an idiosyncratic fascination with pop culture, were rooted in an eccentric personality. In contrast, Robles’s Eighties works are more sparse and formally organized, focusing on poetic allusions and word games based on sensory stimuli, often that of sound.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Filipino installation artist Junyee makes a stand with felled trees

More intellectualized and disciplined compared to other Filipino artists of the time who were also working on boxed assemblages, Robles won the 1986 AAP Annual Grand Prize for Here is How the Transition into the Mambo Beat Looks Like, a dreamy cabinet filled with toys and flights of fancy that was a commentary to the just-transpired Edsa Revolution.

After arriving from Japan in 1995, Robles fused his earlier box-like works with more meditative and minimalist imagery, a result of traditional Japanese aesthetics’ impact on him. An example of this is Relief No. 2: Daan Papuntang Dohoken [Crossing Doho Park] (1997). Composed of a diptych in tan brown, white, and red, the work continues his 80s boxed assemblages, but moves more towards painting, with his austere geometric fixtures looking like a minimalist illustration from a manga scene.

As the new millennium came into view, Roberto Robles became more conscious of his oriental design potential and expressive of the idea of obedience and heroic effort achieved through discipline and perseverance. He was fascinated with Japanese long-distance runner Kiyoshi Nakamura’s idea of zensosho, or “running with Zen.” An avid runner himself, Robles had imbibed this physical discipline that emphasizes continuous effort rather than the final outcome—an Asian attitude opposite the West’s obsession with results.

READ MORE: Fusing Old and New: National Artist Benedicto “BenCab” Cabrera

His Japan sojourn compounded this, and in a sense, has completely taken over his artistic vision. Using the pure whiteness of Carrara marble as his chosen material for his graduate schooling at Tsukuba University, Robles produced a series of trophy-sized totems in 1998. These works, like Ark, Inari, and Quarter Moon show a sensibility that is increasingly inward and meditative. In paintings like Praise Song # 4 and Calm Morning (2002), Robles retraces the act of Zen ink paintings of fragile but sturdy bamboos that speak of the ephemeral nature of life.

Through the use of a monochrome palette of white and black relieved only by earth browns, Robles’s works since 2003 have expanded upon this poetic treatment of nature through painted and sculpted abstractions.

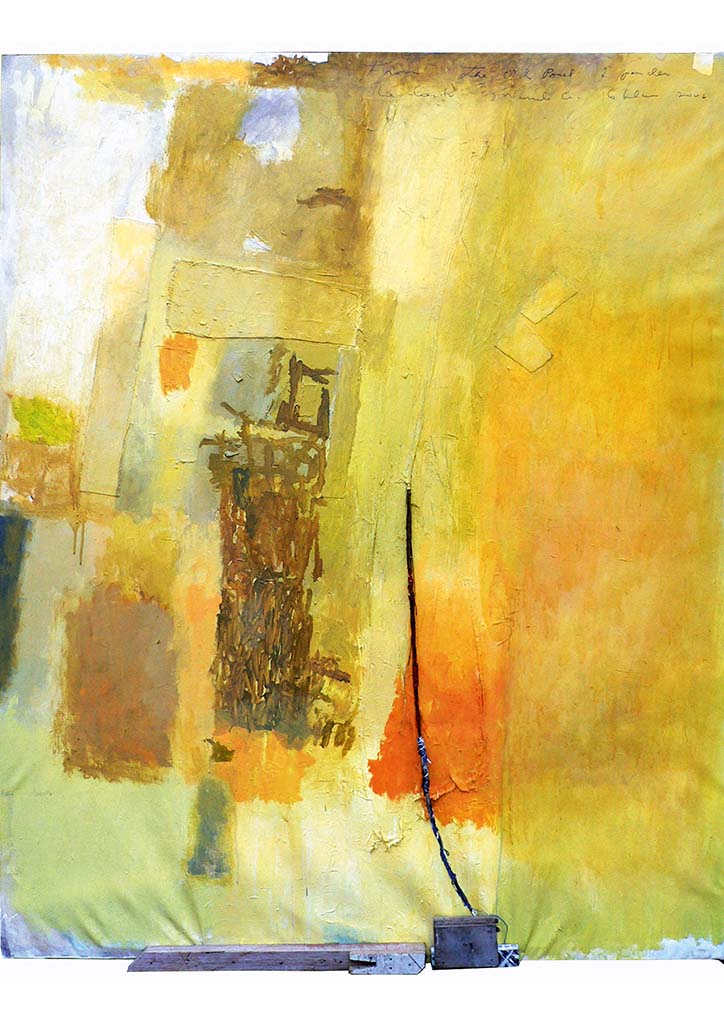

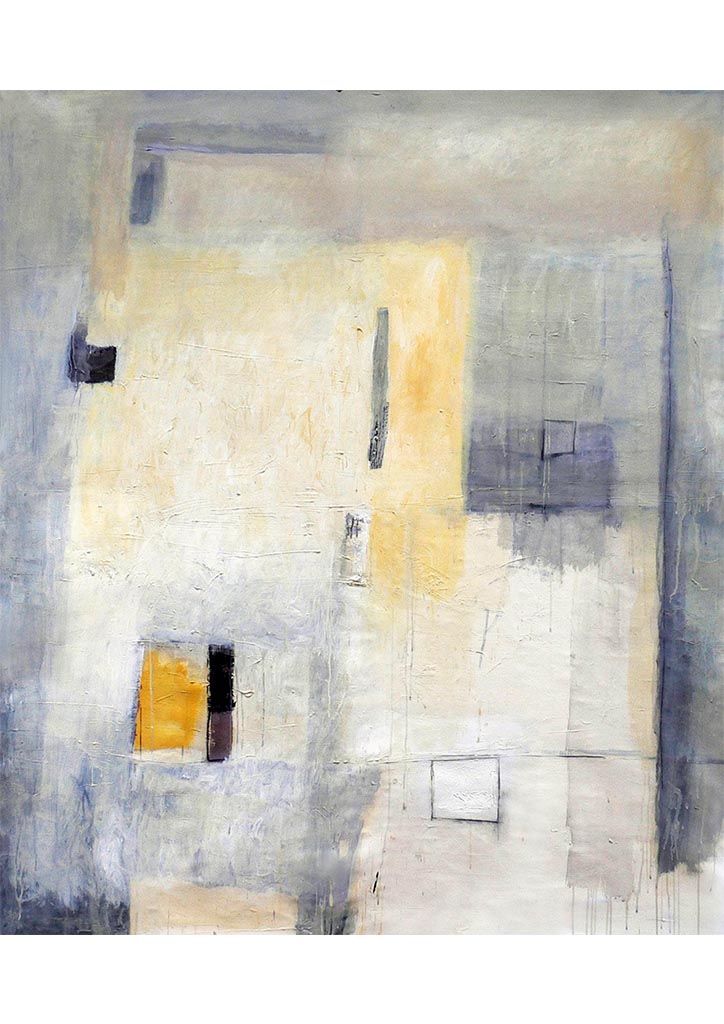

The most constant of these themes deal with water. The immortal haiku that the 17th Century master poet Basho wrote about the sound of water as a frog jumps into an old pond became Robles’s thematic obsession, one that tied his childhood with his acquired Asian artistry. One can see this in the east-meets-west minimalist abstraction titled, Tadpole to Frog III (2005), in which the life cycle of a frog as it moves through water is captured not with figures, but with evocative washes of gray, ochre and black over white. Another is Attending to My Stone: Interrupted Sleep, Ripe Mangoes Falling on the Roof (2007), an assemblage that documents an event in his studio in Batangas. From the Old Pond, I ponder No. 1 (2006) inaugurates a different color scheme, mostly in moss greens that fill the mind with imaginations of duckweed-clogged ponds.

Indeed, Roberto Robles’s works span the range from Filipino verve to Zen silence, only to hear the sound of nature speak its eternal songs of transience.

This first appeared in BluPrint Volume 4 2011. Edits were made for BluPrint online.