LOOK: Filipino artists’ self-portraits from the Paulino Que Collection

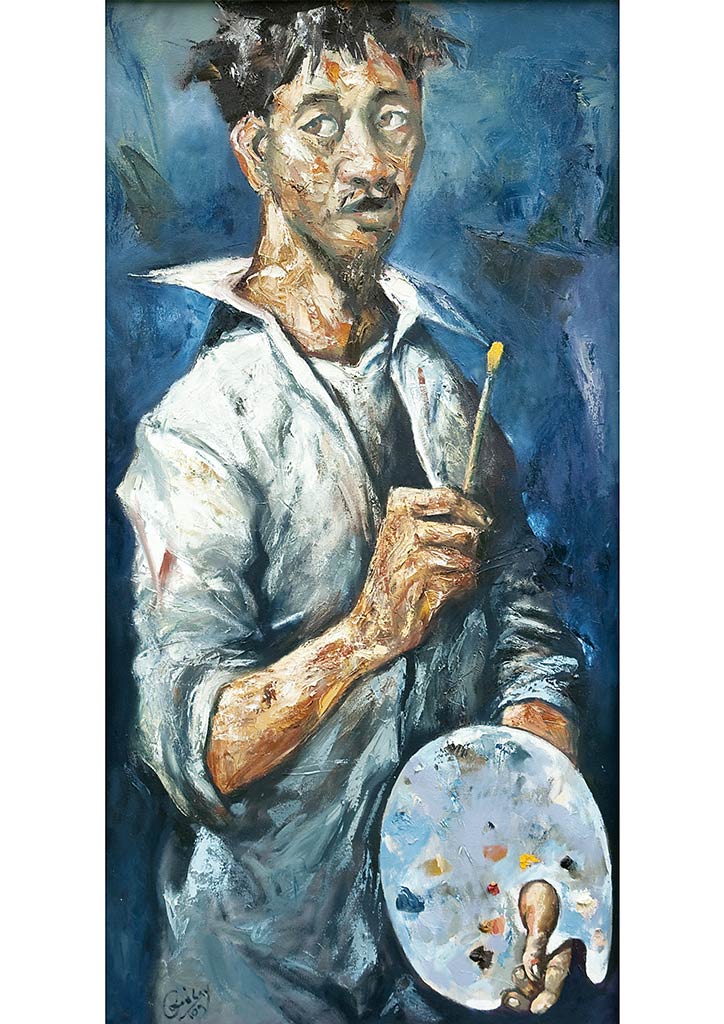

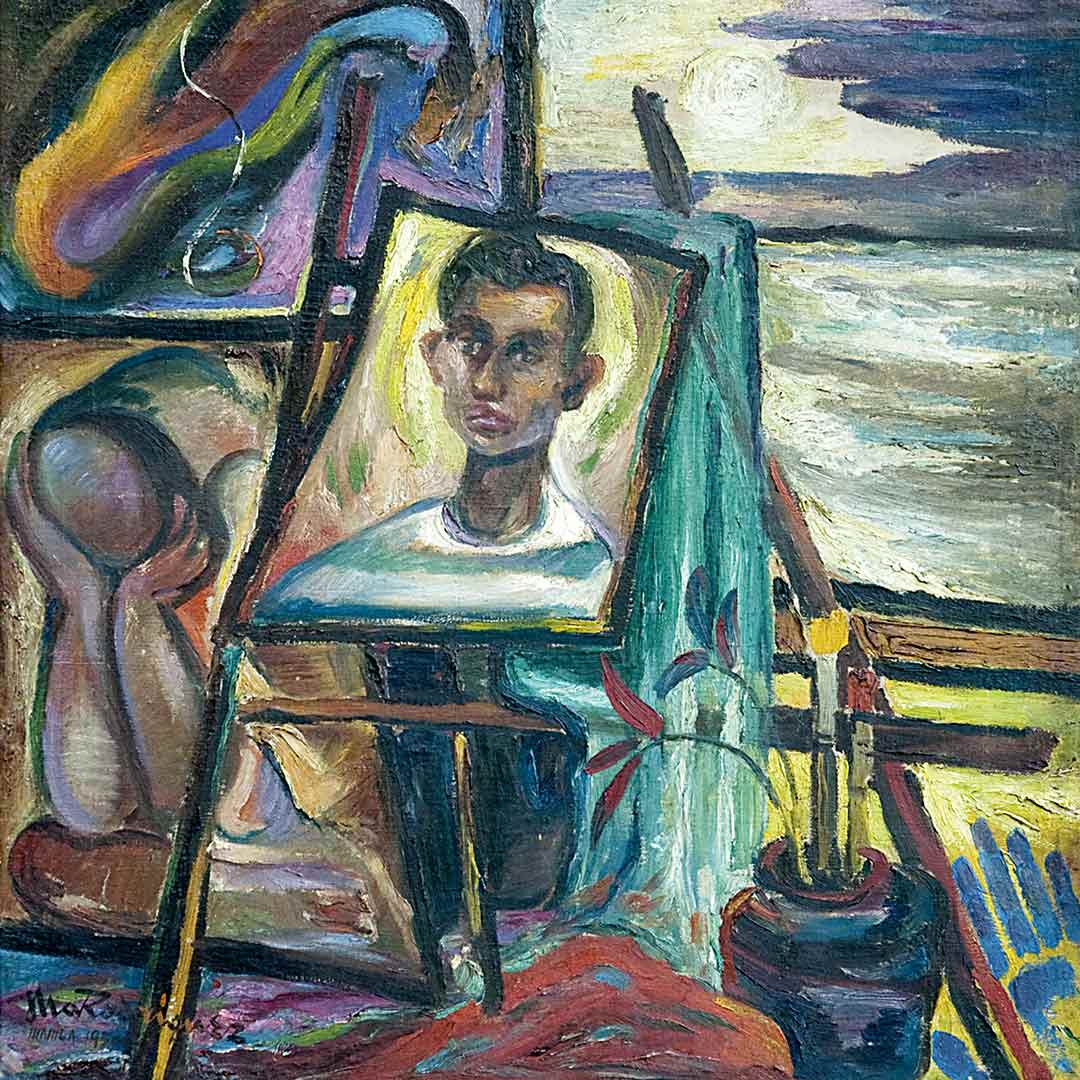

An artist’s self-portrait serves many purposes. For the amateur, it is the cheapest way of acquiring a human model. For more established pros, it is a statement that one has arrived; or that the artist is at par with the princes and saints that he paints, and the patrons and powerbrokers he is often forced to grovel to.

These have been the motivations since the definitive arrival of the self-portrait during the Renaissance. Between the Baroque and Early Modern periods, artists like Rembrandt, Velasquez, Goya, Courbet, and Eakins utilized the self-portrait as a measure, not only of the ability to “mirror” the real world through the mimicry of brush strokes, but also to inaugurate a newfound sense of self-confidence and document the elevation of one’s social status.

For a perceptive number, it was also a means of reflecting on one’s mortality and emotional state, like the self-depictions by van Gogh, Munch, Beckmann, and Kahlo.

Often, these self-portraits are painted using the style or individual means of artmaking that has established the artist’s reputation, making the self-portrait a fair barometer of creativity and uniqueness—the signature of the artist, so to speak. This was especially true of the High Modern and Contemporary periods when an artist’s style would “smash the mirror.” Instead of being merely a copy of one’s reflection, the self-portrait became a manifesto through which the artist declared his “emancipation from the market” through abstraction and conceptualization.

READ MORE: Abstracting Nature: Jose T. Joya and his abstract expressionism

These multiple motives are therefore what makes collecting artists’ self-portraits popular. The oldest and most famous collections are at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and the National Portrait Galleries in London and Washington.

Here in the Philippines, the solemn duty to collect self-portraits as an encyclopedic means of assessing the true nature of the Filipino artist has been undertaken by noted art patron Paulino Que, whose own collection of about a hundred Filipino self-portraits ranks as one of the most significant in the country since the demise of great collectors like Alfonso Ongpin, Aurelio Alvero, Jorge Vargas, and Roberto Villanueva.

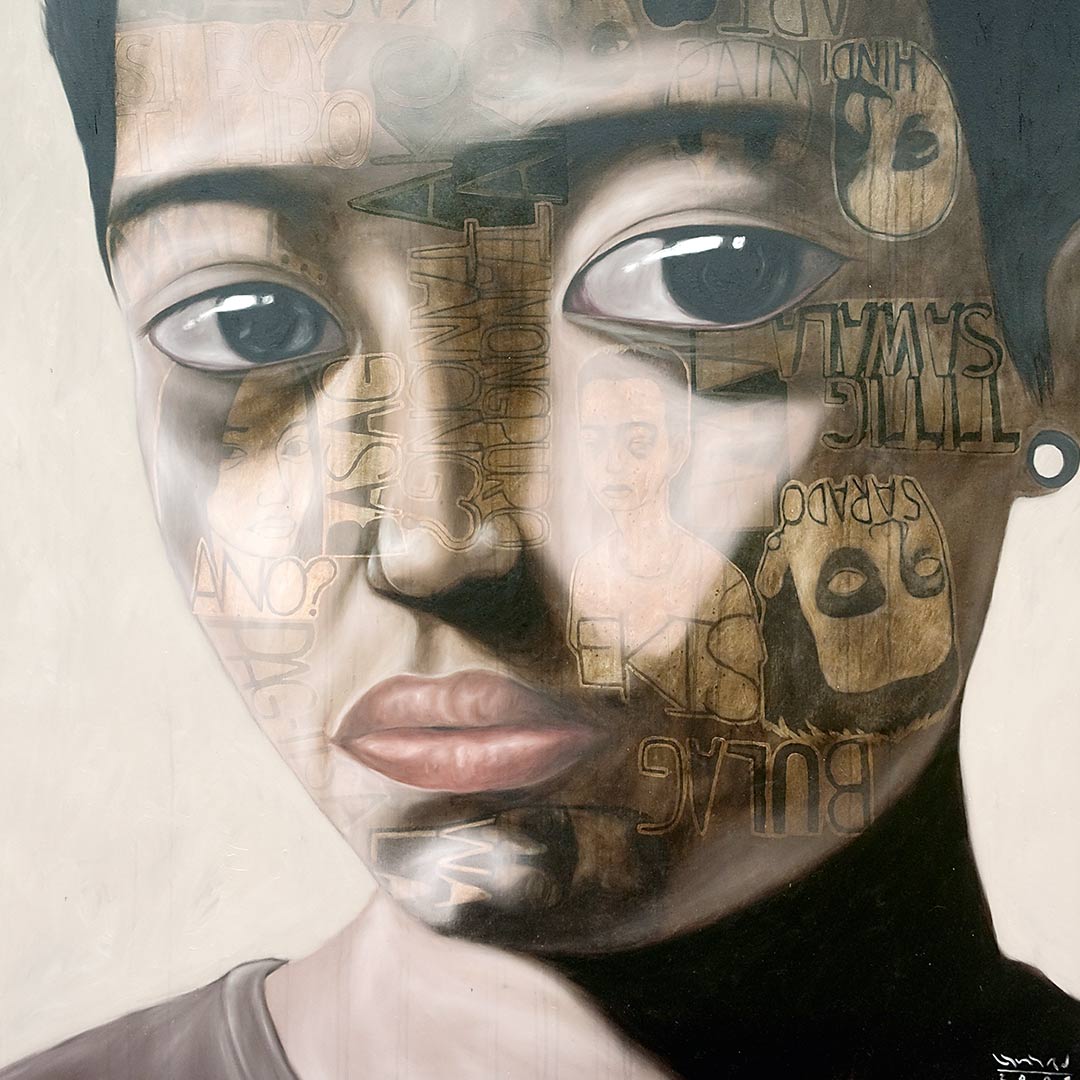

Containing both the “classics” of the past like Fernando Amorsolo, Juan Luna, and Victorio Edades; abstractionists like Federico Alcuaz, Fernando Zobel, and Pacita Abad; as well as the most cutting-edge, avant-garde art of today from the likes of Annie Cabigting, Nona Garcia and Ronald Ventura, the Paulino Que Collection is a vital archive of trajectories in artistic expression that begs to question: What does it mean to be a Filipino artist in the modern—if not contemporary—condition?

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Heritage lost, found, and reborn: The Escuela de Bellas Artes in Bagac, Bataan

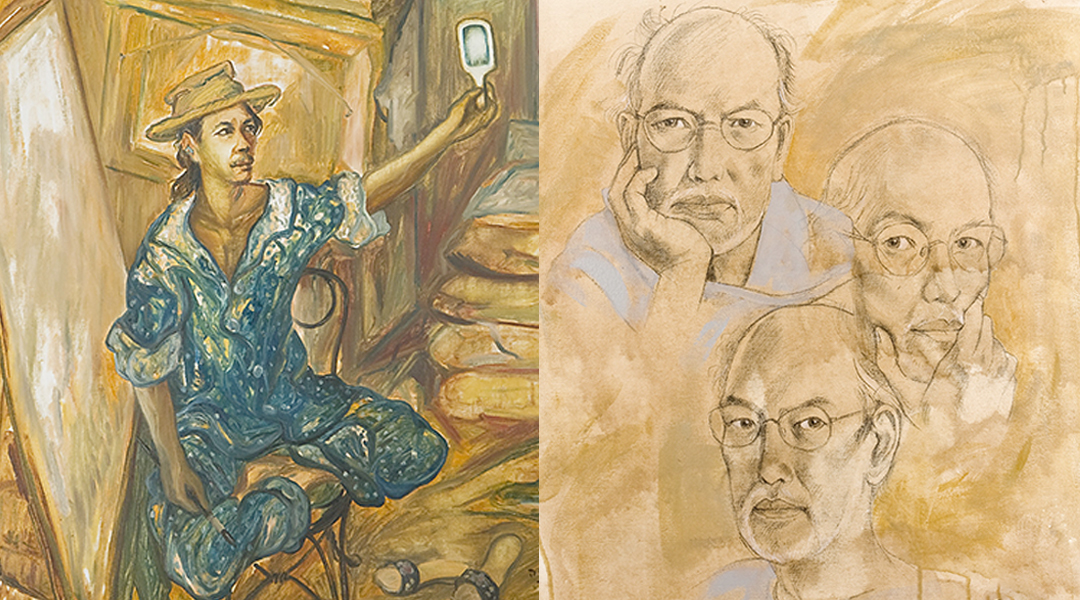

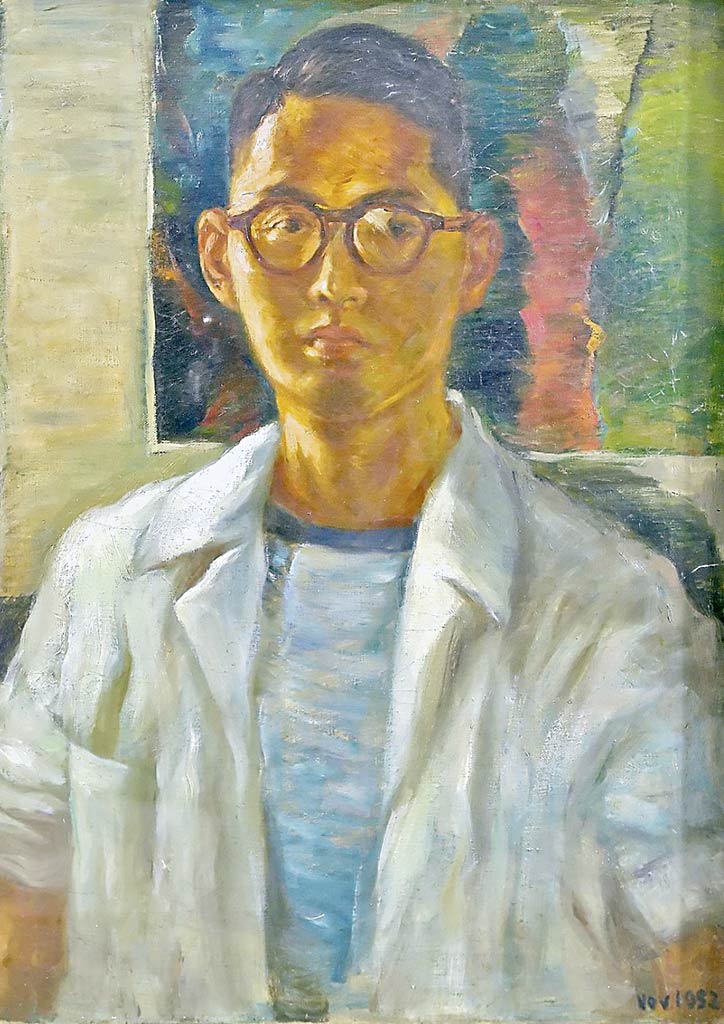

The Looking Glass

Art as a mirror is the oldest and still most pervasive idea in portraiture. Allied with the idea of the canvas as a window into an imaginative but nonetheless recognizable world, the Looking Glass metaphor basically reflects what the artist sees, a reproduction of the real world: flesh and hair, eye sparkle and cloth shimmer, light and shadow. This is filtered, of course, through the vagaries of style that make the work unique—from the sunlit dapple of Impressionism to the stormy bravura of Romanticism, and the clinical cut-and-paste of Hyperrealism.

Painted into an ivory base the size of a fob watch or choker pendant, the self-portrait of Damian Domingo is perhaps the earliest example of local self-portraiture. Dressed in a fine naval uniform, Don Damian stares out of this tiny space with all the command and self-assurance that the self-made artist could muster in this period of relative liberty for the colonial indio. Miniatures like these were the bread and butter of Don Damian, commissioned by patrons as mementos to their sweethearts or prospective brides in that era of strict gender divisions, when a glimpse of a lover in the upstairs ventana from the street was all the thrill one had. Don Damian painted these with incredibly tiny brushes made from human hair.

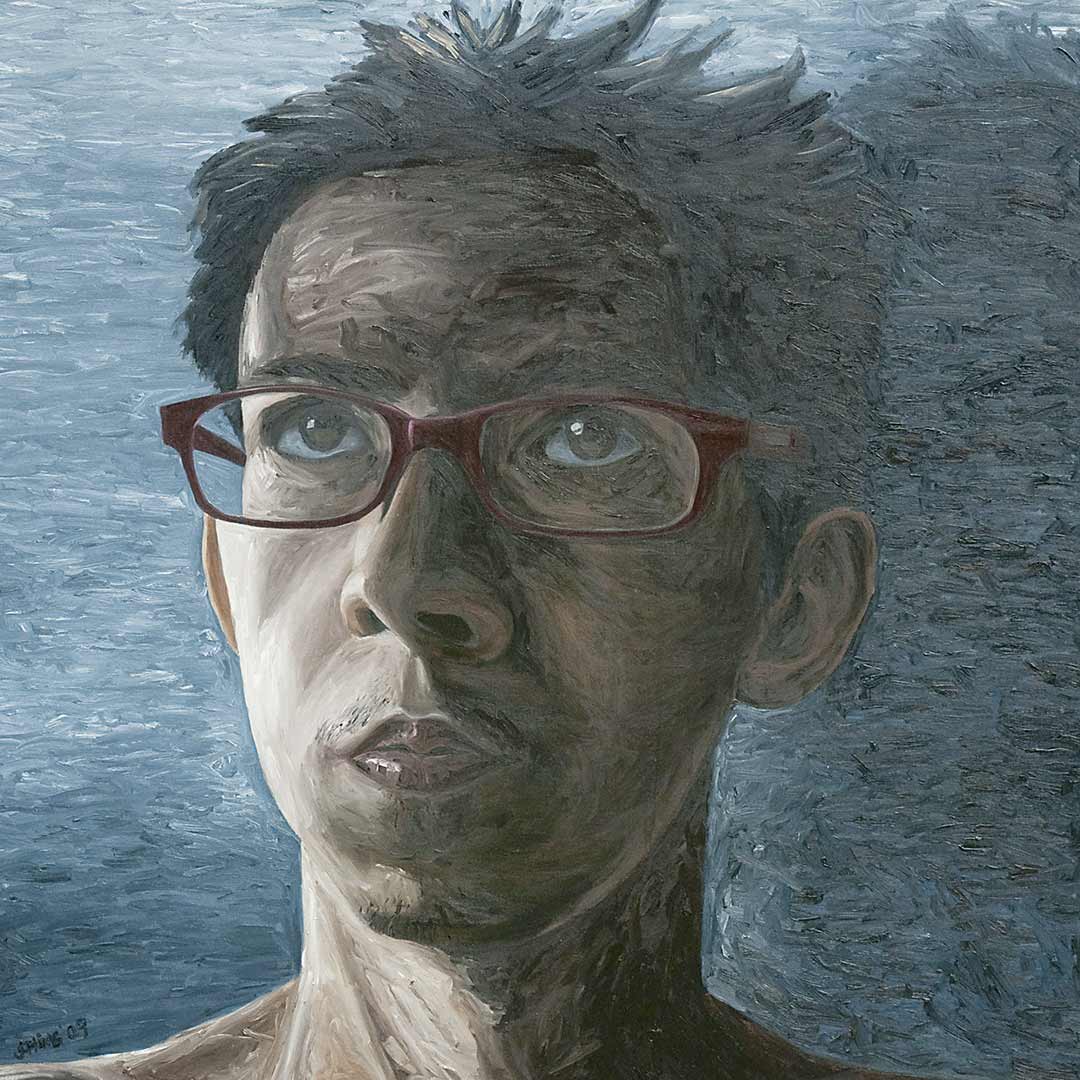

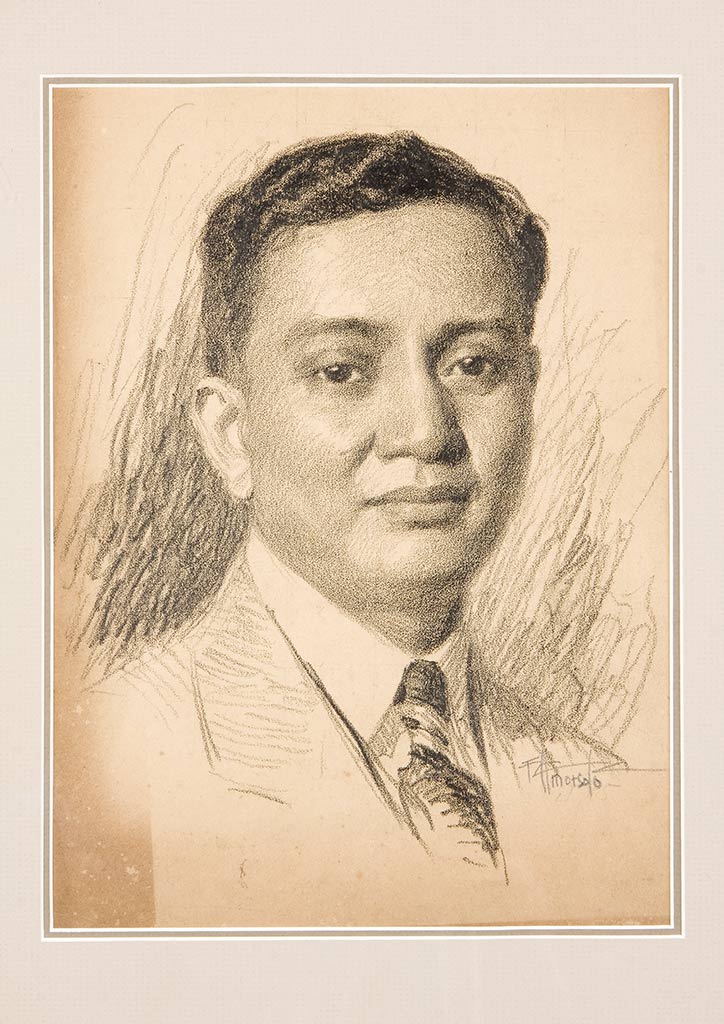

Drawn with the academic self-assurance derived from his reputation as the most successful artist of the pre-war years, Fernando Amorsolo’s bravura self-portrait in pencil fixes us with a gaze both confident and somewhat weary, as his teaching duties at University of the Philippines, combined with his constant commission work (working on at least four paintings at a time) was exhilarating and exhausting in equal measure. The sense of mastered illusion as well as informality in the unfinished quality of the portrait marked his particular version of academism and the Beaux-Arts sensibility.

READ MORE: St. Joseph’s College: A treasure trove of faith and art

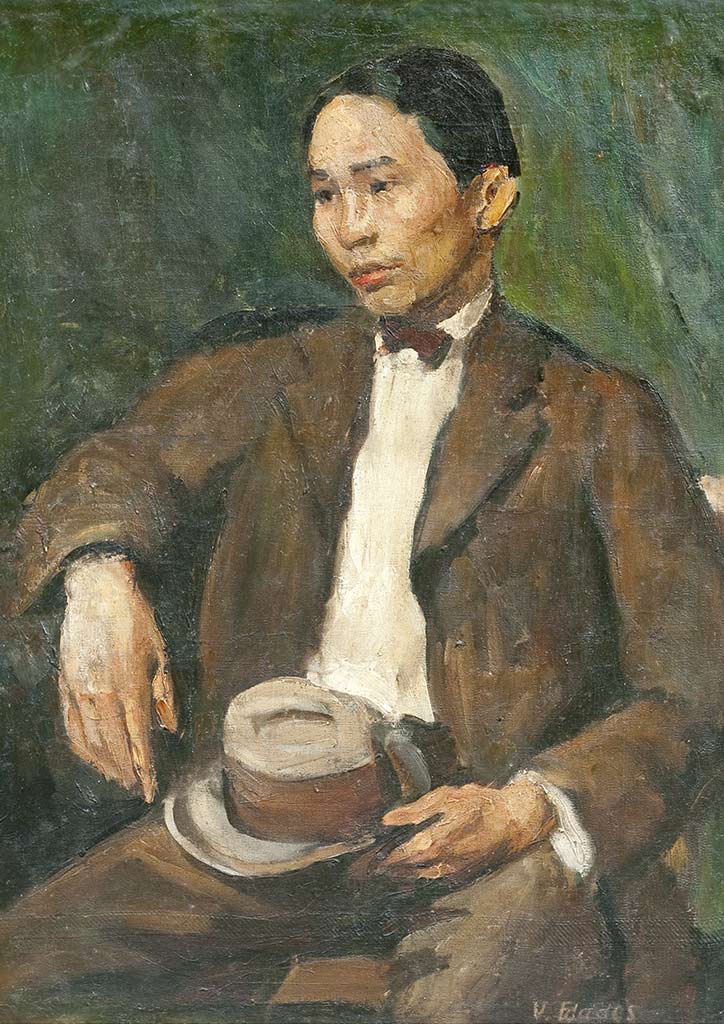

Depicting himself as the laboring gentleman caught in the grip of the Expressionist sublimity of late Twenties America, Victorio Edades paints himself with a weariness that exhausts the body and numbs the mind. Perhaps reflective of the stresses he was under at the time (finishing his masters, and marrying his white fiancée despite America’s miscegenation laws), here is Edades both tense and still, as if waiting to stand up from his chair at any moment to attend to the white sorority students’ heating and plumbing needs.

As a vigorous rejection of classical norms, and yet an affirmation of its mimicry appeal, Annie Cabigting’s self-portrait captures the artist as a viewer herself, her back turned away from the audience to focus on an enormous painting-within-the-painting. The idea of withholding one’s face from scrutiny is a double statement against both the academic fetish for gazing at female bodies; as well as focusing our attention on what matters for her—the artwork itself.

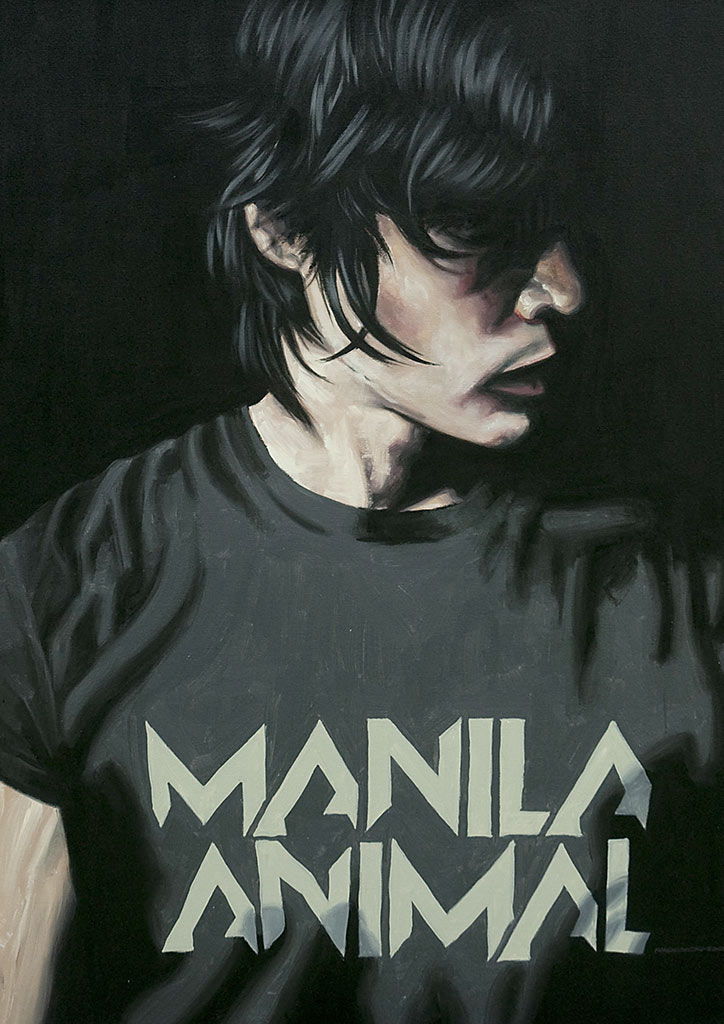

Kiko Escora’s averted gaze in his self-portrait, throwing his face into shadows, while highlighting his tense young body clad in a black “statement shirt,” is a study in effaced narcissism. The contemporary values of “star quality” and the sex appeal of youth at its prime are nonetheless evident in this “aw shucks” moment of affected humility, signaling the artist’s own ambivalent attitude about celebrity and the impact of contemporary fashion photography.

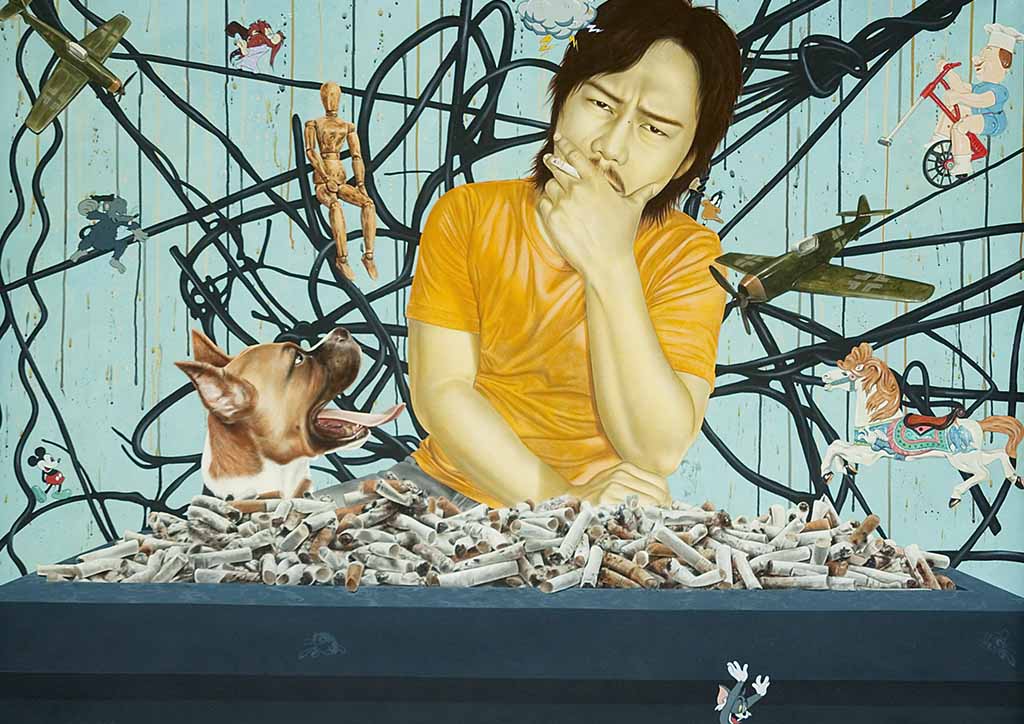

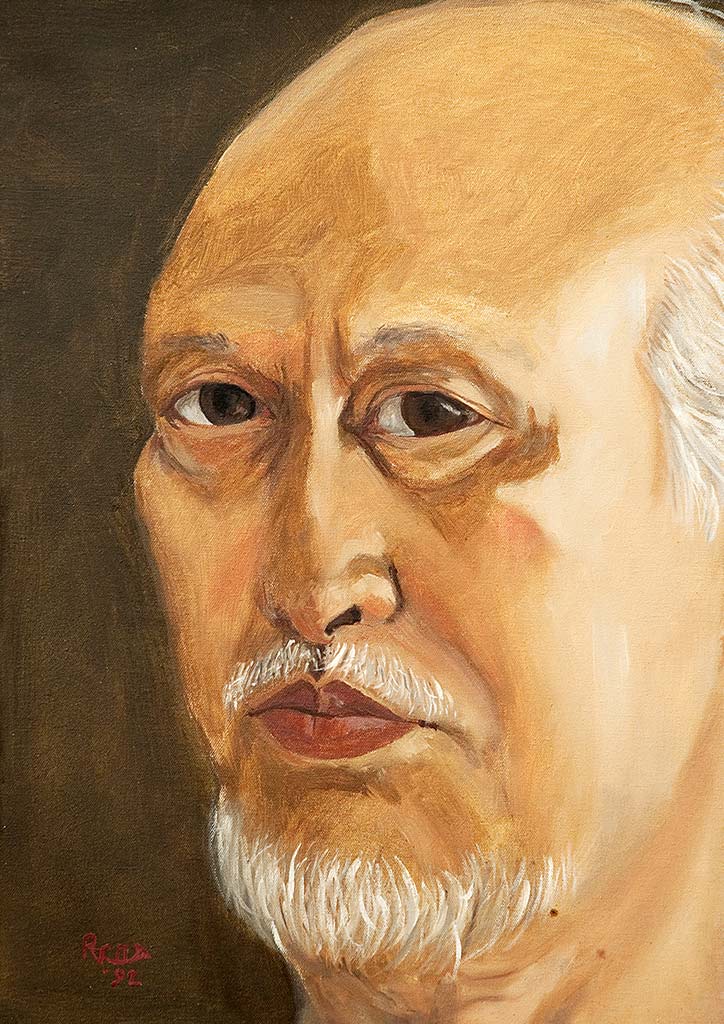

The Dark Avatar

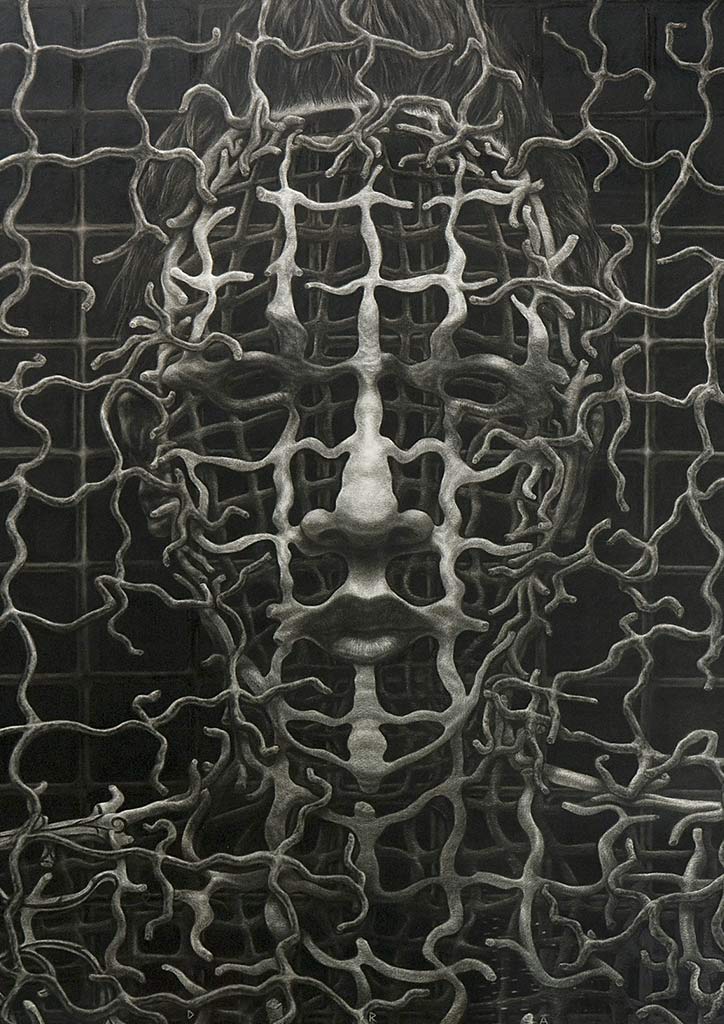

The expressionistic or surreal portrait was brought about by Modernism’s rejection of traditional depictions of reality “as an ideal image of what is.” It does not dwell in bland depictions of the self, or even in describing a real world. Rather, fantasy, emotion, and an often-nightmarish world, where the artist appears alienated from his or her surroundings, brings out the dark twin of the Mirror, which I call the Avatar. Unlike idealized reflection, the Dark Avatar is a stylized transformation of reality into brooding, dysfunctional, or conflicted depictions of the self, and the individual’s struggle to liberate one’s self from the drudgery of modern life.

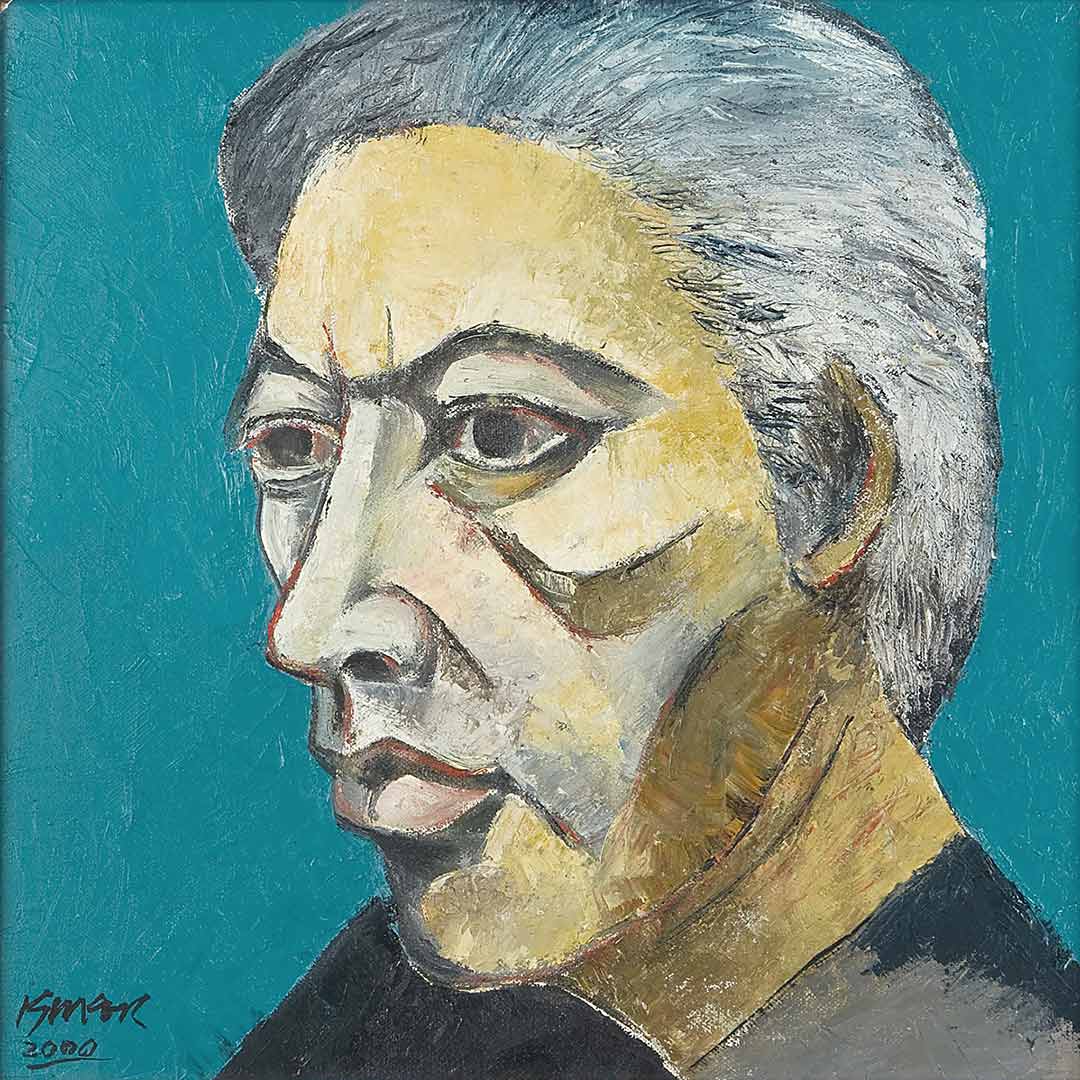

Made with a brisk but calculated homage to his Expressionist forebears, Ang Kiukok’s self-portrait, done in his last years, was a monumental mask of emotional reticence, whose solidity and sculptural quality makes it comparable to the Italian Giorgio de Chirico, or Mexican Rufino Tamayo. Atypically calm compared to his often gory and shell-shocked depictions of people, Ang’s self-portrait seems to be a summation of the virtues of patience and introspection that his Chinese heritage typified. The only thing out of place here is the red lined eyelids as if the man had just gone through mourning.

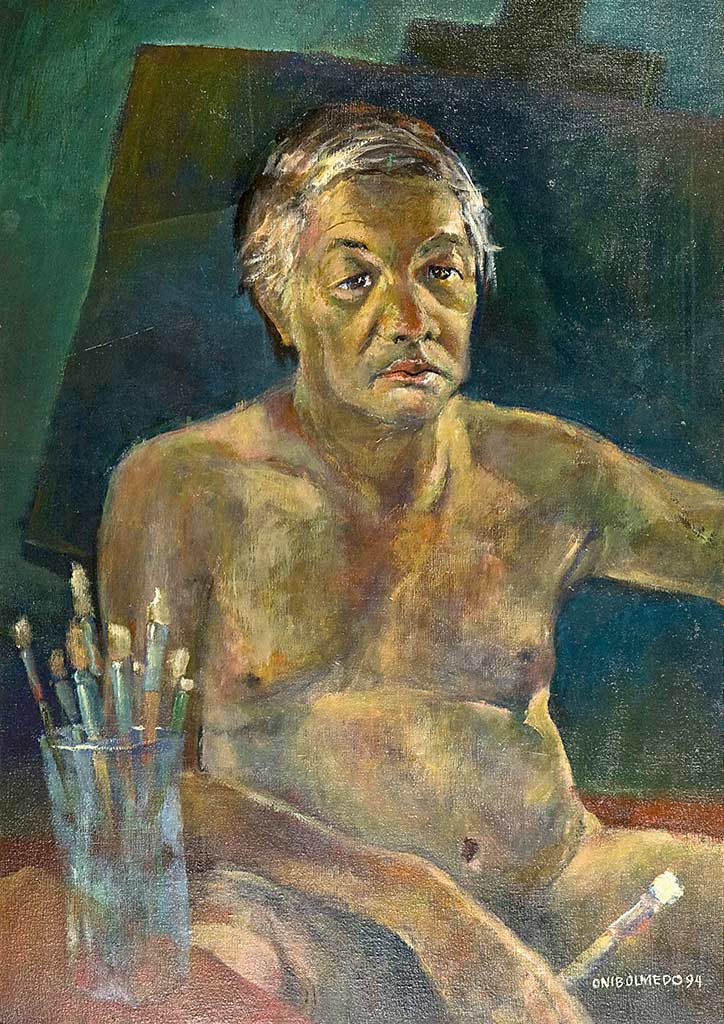

Onib Olmedo was a master of capturing the despair of modern life. Here, he depicts himself in the nude, with only a paint rag draped on his leg, and surrounded by his paintbrushes and easel. The sense of resignation and misery is palpable in his sharply defined face, and leap out from his sagging, corpulent body with a seeming plea for help. Within a year after completing this portrait, he would be dead.

Combining the mania of a carnival with the melancholia of depression, Charlie Co’s self-portrait, executed after his near-catastrophic visit to Japan, and the discovery of his diabetes seems to be a reflection of the artist’s internal dilemma regarding his future directions. Depicting his body as part of the same colorful landscape that inhabits his apocalyptic world time and again, Co’s monologue shares the sense of quiet despair and hope that animates Frida Kahlo’s work but is wrapped up in a charming façade of confectionary emptiness that has always characterized Co’s haunting vision of his homeland in Negros Occidental.

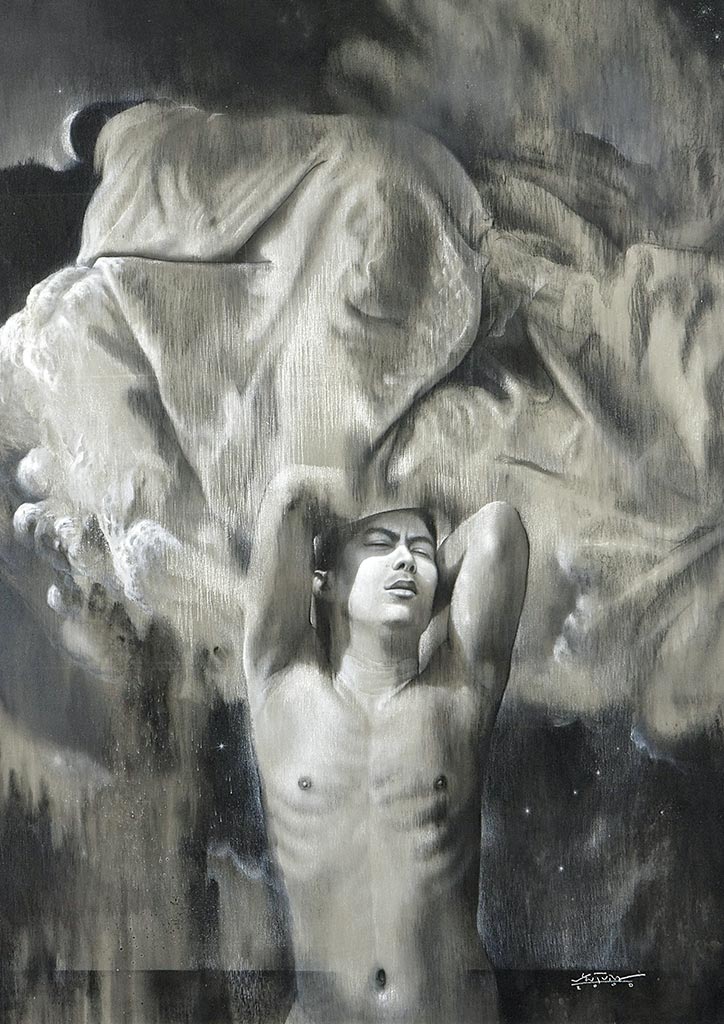

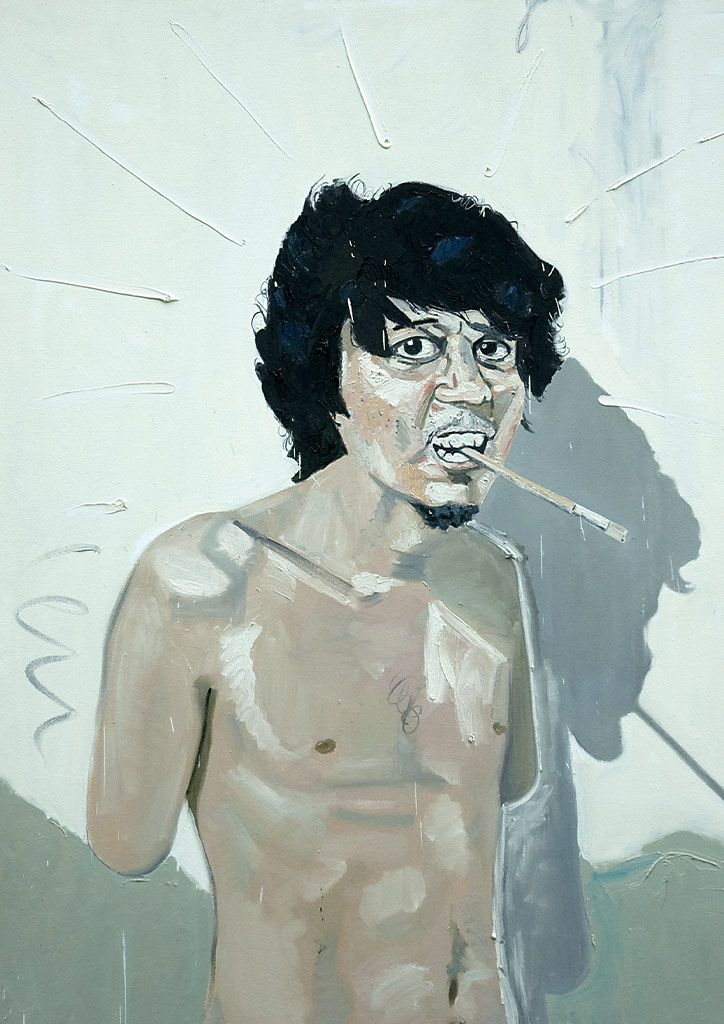

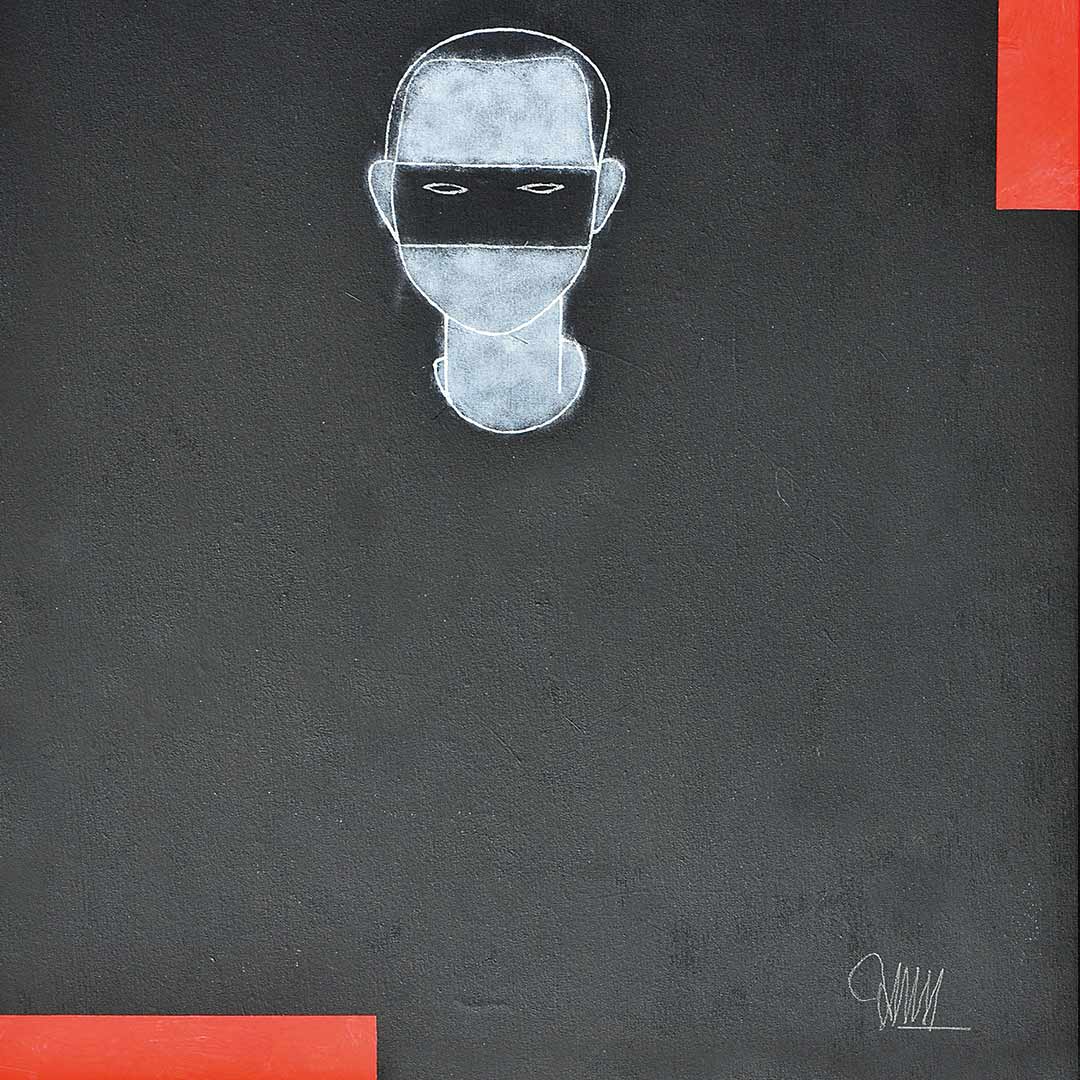

Executed just before his dazzling rise to the top of the international auction heap, Ronald Ventura’s self-portrait is an early summation of his artistic philosophy: the use of monochrome, the surreptitious sense of voyeurism, and the refusal (or perhaps acquiescence?) to engage in the viewer’s objectifying gaze are all there, as well as his renowned ability to make his bodies look marmoreal, even vampire-like. While sex is, of course, just one aspect of being the Undead, Ventura’s dark reflection of his being that apparently augurs the arrival of the “sleep of reason” (that Goya had so rightfully mastered) seems to be just that—a put-on. This artificial quality is ironically the very thing that has made him collectible. People are in on the act, so to speak. The only question in people’s minds is his fidelity to the visual technique.

READ MORE: Modernist Avatars: National Artist Jeremias “Jerry” Elizalde Navarro

The Jester

Not taking oneself too seriously is a humanistic undertone found in many Modern and Contemporary portraits. The Artist as Jester is meant to both disarm the public, as well as reassure them and the artist, that this depicter is all too mortal.

Sometimes, the self-portrait is taken as an invigorating antidote to the deadening output that an artist has “standardized” and must churn out for the sake of his patronage base. The self-deprecating gesture functions like an “inside joke” that only the artist and those closest to him would know—a sly comment on one’s ability to “see you seeing me seeing you.”

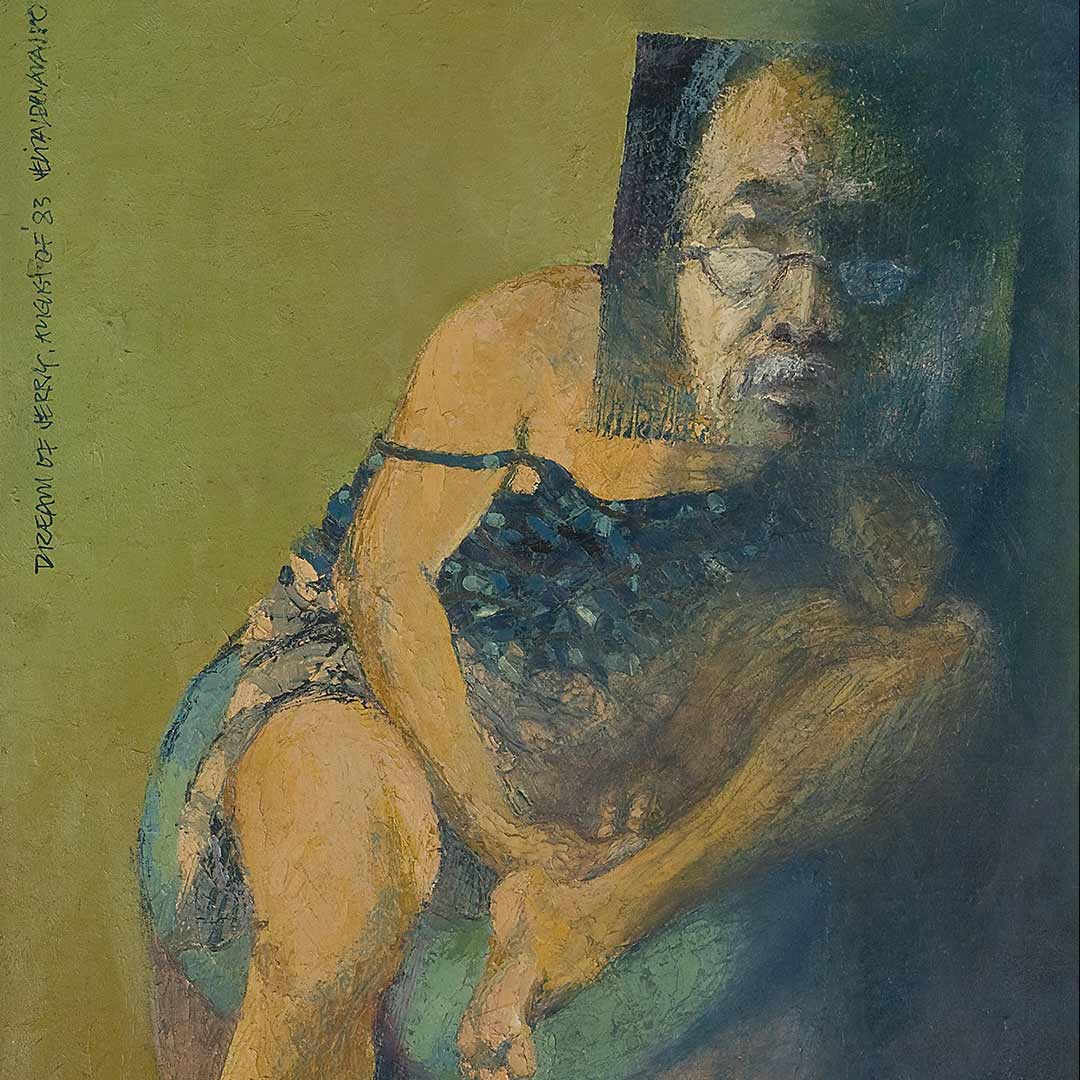

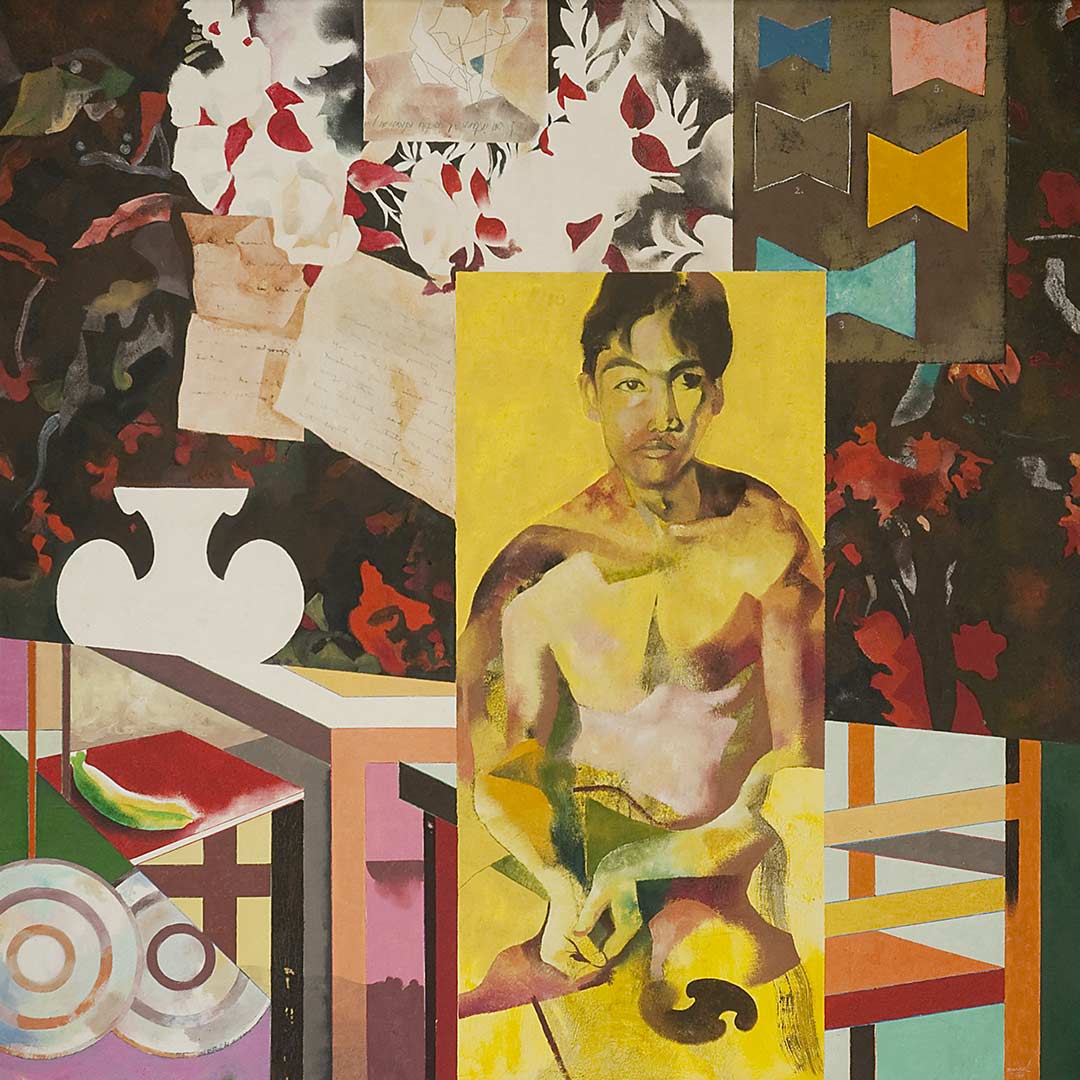

A sly, tongue-in-cheek double portrait that J. Elizalde Navarro executed between himself and his beloved second wife Emma, The Dream of Jerry speaks of longing and togetherness that defines intimate human relationships. This is brought out through the very act of effacing Emma but retaining her body and replacing her portrait with his own. This results in a doubled identity that sings of the mutual and conflated nature of Jerry/Emma as interchangeable partners and lovers.

Continuing his assault against institutional authority and reveling in the “bad boy” spotlight, Manuel Ocampo’s self-portrait, though not as controversial as his other work, still stings with its rejection of legitimacy. Here, he plays an angel (or a “fairy”—get it?) from the Apocalypse embellished with the Nazi swastika, blowing his trumpet at a nearly prostate Saint John surrounded by crosses. The telon quality of the painting is deliberate and part of Ocampo’s style, but it is the iconography, with its “devilish” attitude towards religion that is his true signature to this piece.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Morality Tales: The quintessential art of Manny Garibay

The Dissimulation

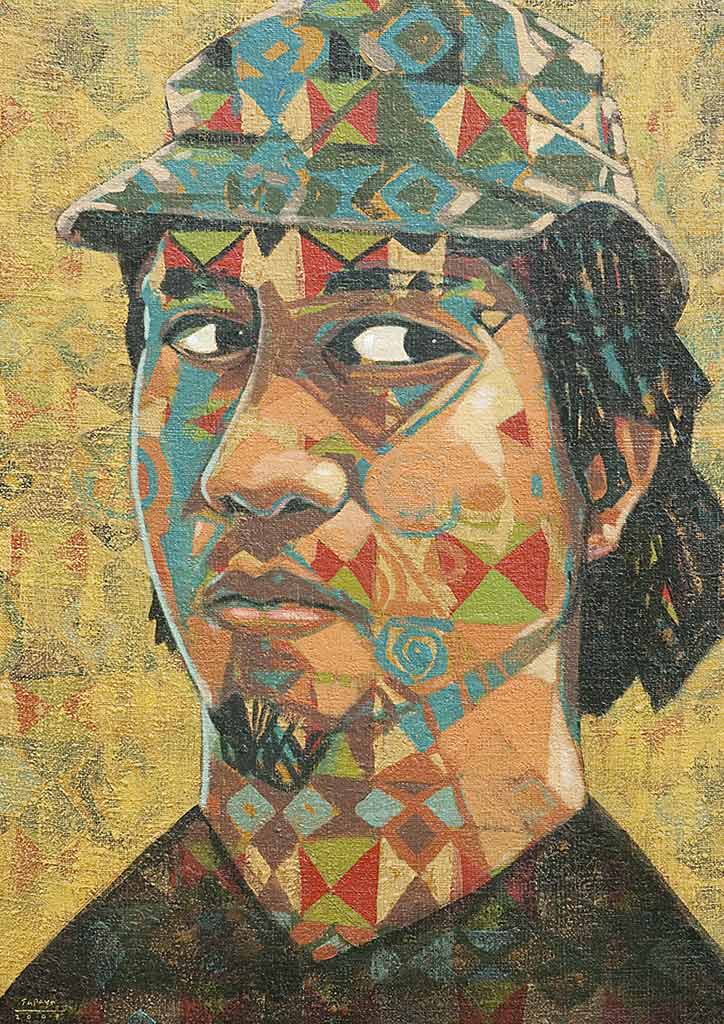

“Making strange” is a concept borrowed from Russian Formalism, where the drudgery of depicting the reality of the world is spiced up by effects and devices that force people to pay attention not only to the detail, but also the message hidden in plain sight. This is a favorite process that many Modernists and members of the avant-garde resort to, in order to differentiate themselves from mere “mirror-copiers.”

Inserting favorite compositional devices and reformatting the portrait into a statement that “a painting is a process of making, rather than a window to look into” also counts as its primary appeal.

Typifying his mastery of geometric and linear abstraction, Arturo Luz’s self-portrait uses the classic red-and-black with white contrast that has marked his work from the Sixties. However, he shows a distinct adaptation of his stark white lines and scrambled patches, resulting in a recognizable portrait of the artist, with the thin swept-back hair and angular face. The need for facial detail is removed via his expert addition of an austere mask, which is consistent with his depiction of the world through his trademark geometry.

READ MORE: The Enlightened Maestro: Martino Abellana, the Amorsolo of the South

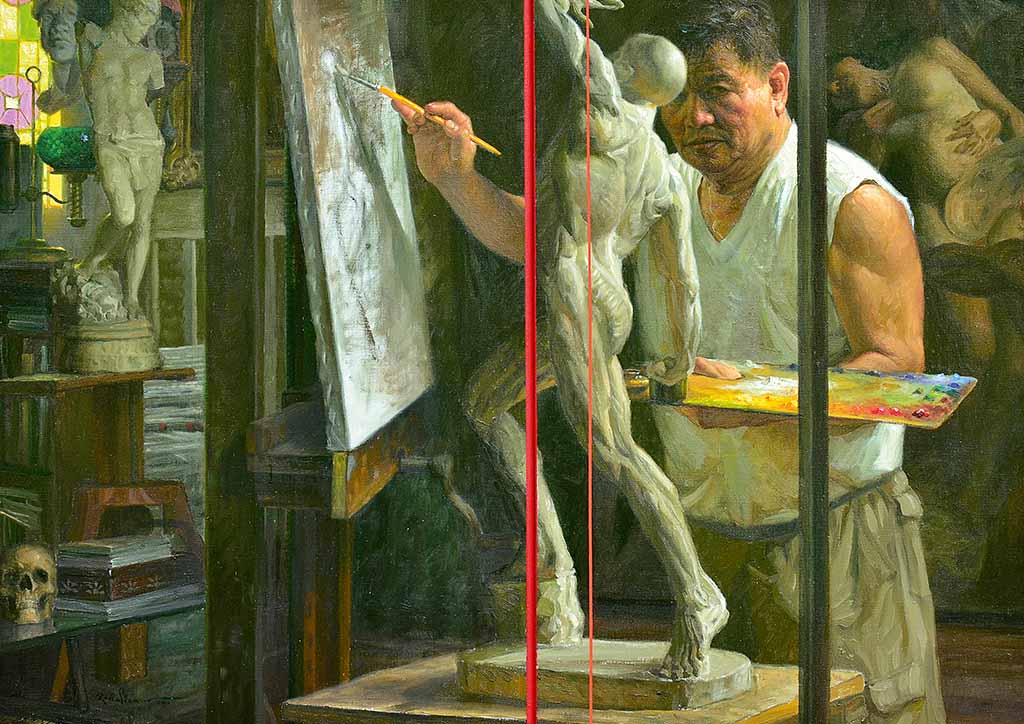

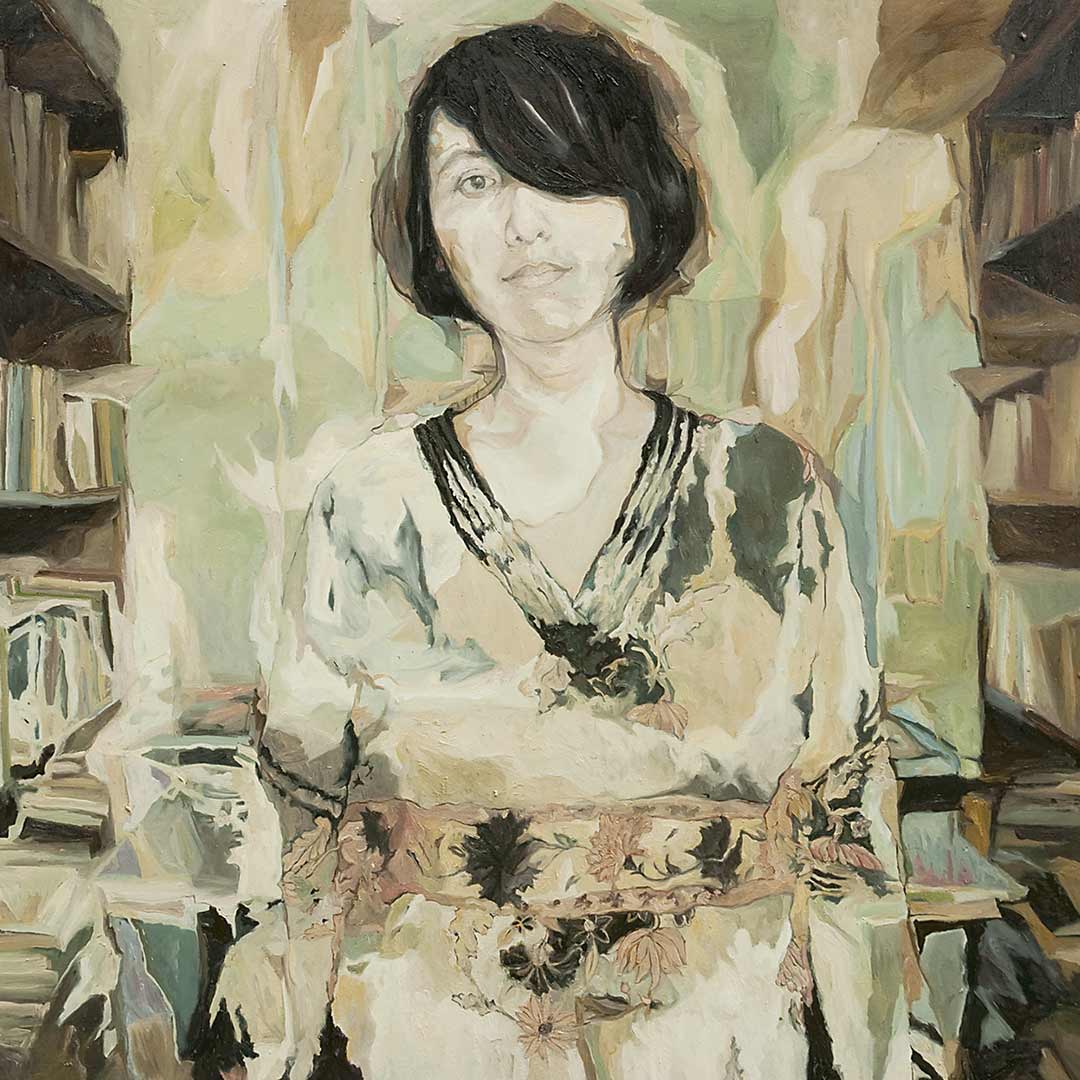

At first, a seeming exercise in Neo-classicism, Romulo Galicano’s self-portrait becomes increasingly fragmented upon closer inspection. First, his distinct vertical colored lines and “zips” bisect the image like film scratch. Then, he alternates our view from his own visage, which is partly obscured by a sculpture in the foreground, and the myriad views of his crammed studio, where every detail vies for attention in between the zips. Ultimately, the mélange of academic and abstracted forms forces the viewer to think about the need for such a combination. It is here that Galicano shows his ability to pull our complacency apart in order to see the “in-between-ness” that for him characterizes great art.

The Homunculus

The artist portrays himself not as the world sees him in the flesh but through the body of work that best represents his art. Often, Conceptual Art and other forms of Modern and Contemporary styles and movements use this approach, as the concern of the artist is not so much to go back to an artistic problem (“depicting oneself”), but to “go forward” by using their style to state their own identity as an artist that is defined by the portrait.

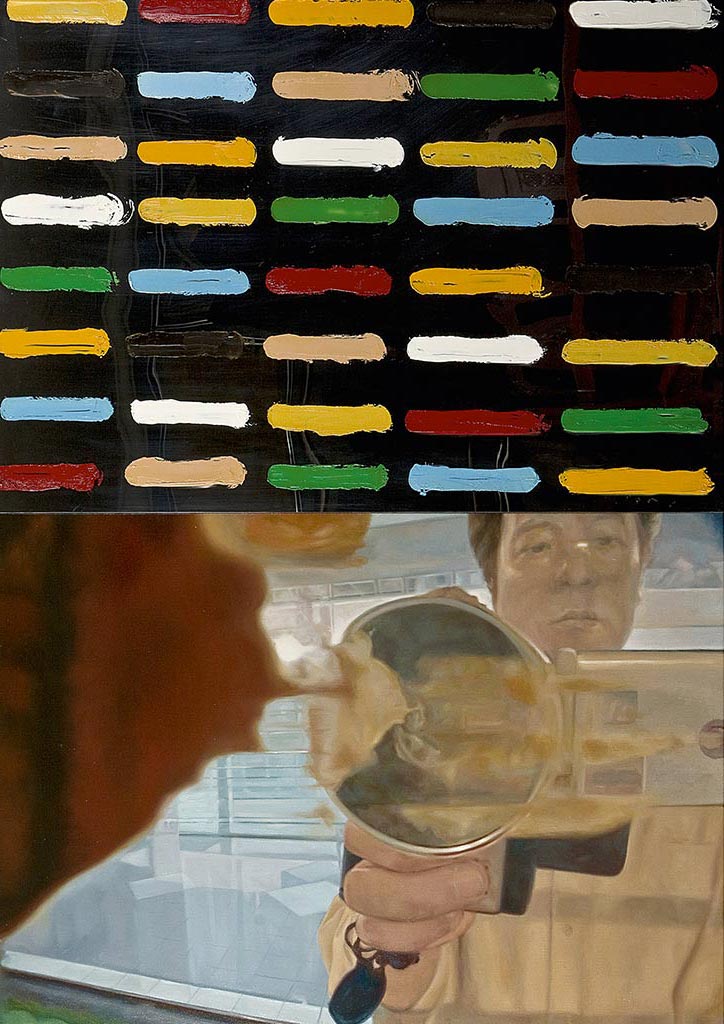

Combining the conceptual artmaking process that is his and his mentor’s hallmark, Gerardo Tan takes on the idea of self-depiction through typically technical methods. He organizes color swatches on the top to indicate the color palette that he used for the painting and then shows the resulting combination on the lower part, a painting on a mirror that overlays each segment that Tan saw from the mirror. This results in a painting that is both visually recognizable and still adheres to the dictum of Conceptual Art, in which the idea, not the resulting image, is the point of the artwork.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: When Worlds Mutate: The Abstractions of National Artist Hernando Ruiz Ocampo

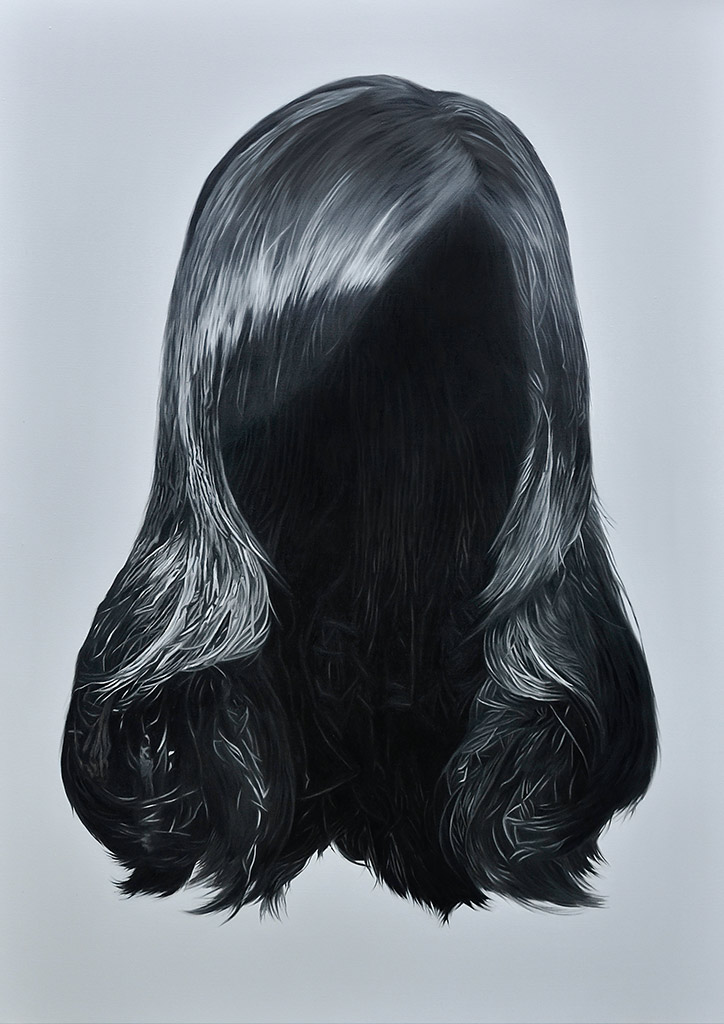

Another contribution to the spirit of Conceptual Art, Nona Garcia’s self-portrait rejects the depiction of the face as a statement of both feminist principle as well as the inanity of a “complete” but mind-numbing image. Instead, Garcia suggests her presence by depicting only her hair, but in a Hyperrealist and almost clinical way. This once more connects to Garcia’s own visual explorations of materials depicted in hyperreal but attenuated (thus incomplete) ways.

Reveling in the principle of Postmodern simulation, MM Yu’s deft collage of altered digital photographs depicts all possible images of the “double M,” which stands as her artistic statement of belonging to the here and now of contemporary global culture. The march of double M’s reads like a shopping list of global and local (glocal) brands and pop-cultural signatures, from McDonald’s to M&Ms, corporate logos to newspaper clippings, and from store signage to fast-food packaging. Yu thus questions the very nature of human depiction by turning the camera around to show the environment, where we exist in a precarious state of consumerist imbalance.

Unlike buildings and interiors, paintings stand up to better scrutiny when the subject concerned is the identity of their maker. In fact, stylistic distinction is the primary factor that drives Modern and Contemporary Art to be “unique and creative.” Hence, the body of work of one artist is immediately recognizable from another, even in such details as eyelids and fingers, not to mention color blocks and mixed media techniques.

This is not to say that architects and interior designers cannot have a signature style that can be argued as a “self-portrait.” Many of the most famous, from Wright to Nouvel, have buildings that are so distinct that they may as well be portraits of their designers. It relies on a high level of design distinction that breaks away from the mass of mediocre copying, as well as an ideological commitment to this distinctly Modern idea of the autonomous, sometimes suffering, but ultimately redeemed designer as artist (shades of Ayn Rand’s Howard Roarke, to be sure).

Now if only buildings were more collectible.

This first appeared in BluPrint Special Issue 3 2012. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

READ MORE: Fusing Old and New: National Artist Benedicto “BenCab” Cabrera