When Worlds Mutate: The Abstractions of National Artist Hernando Ruiz Ocampo

In the fifties, the world first glimpsed how life as we knew it might end. The nuclear weapons testing that was then going on unabated produced monstrously-shaped plants, horribly deformed animals and sickened humans irradiated near testing sites in Nevada and the Pacific. At the time, people feared that if the pace of superpower rivalry between America and the Soviet Union continued, the world would indeed end in a nuclear apocalypse, leaving only mutated life-forms to survive and feast on humanity. Sci-fi fantasy films about radiation-strengthened mutant monsters wreaking havoc on civilization became avidly patronized by the public, such as the Japanese cult classic Gojira/Godzilla, and the now less-remembered Hollywood B-movie, The Beginning of the End. Filipino artist Hernando Ruiz Ocampo (1911-1978) managed to channel this fear of tomorrow into a compellingly modern motif that would result not in human catastrophe, but in aesthetic success.

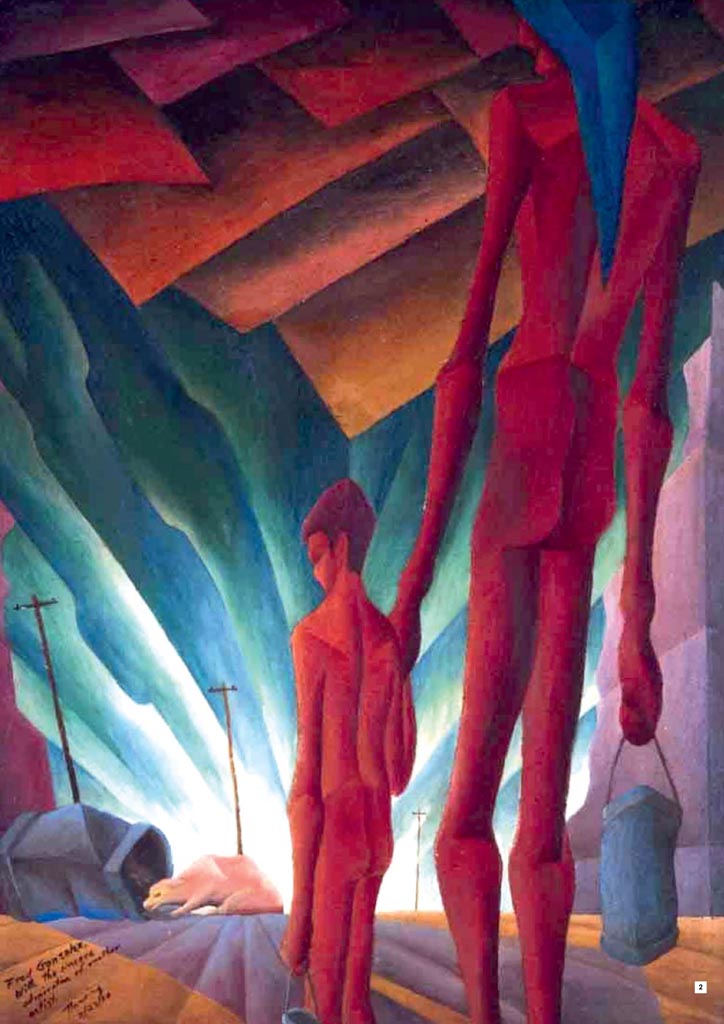

Ocampo, posthumously declared National Artist in 1991,was a novelist/co-founder of the influential Veronicans, and editor of the Sunday Chronicle Magazine. A committed nationalist, he depicted the conditions of the poor and downtrodden in numerous short stories and essays. His nationalist views would influence him as he expanded his artistry from letters to painting starting in the mid-1930s, using a social realist theme with art deco-style cubistic divisions that persuaded Victorio Edades to claim him as one of the Thirteen Filipino Moderns in 1939. After the war, his sensitive appraisal of the nuclear arms race and its effects upon popular culture dovetailed with his ambition to produce a truly indigenous modern art style that did not depend on artistic motifs imported from New York.

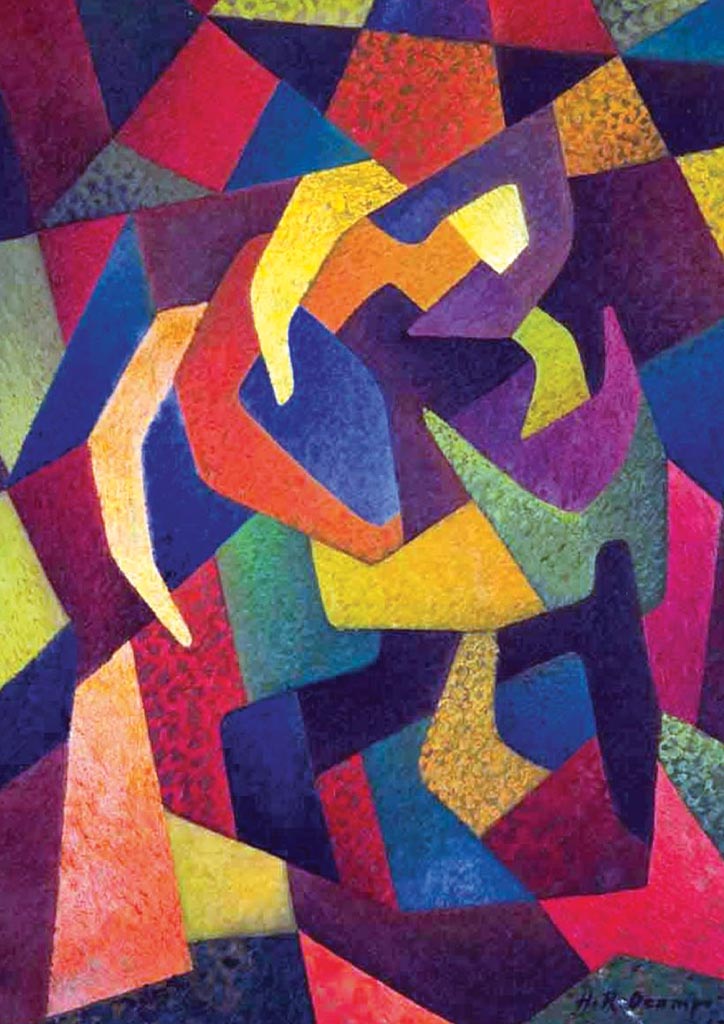

The result is most famously addressed in his pioneering 1950 work Mutation, which illustrates cell-like amoeba or bacteria dressed in polka-dot patterns and brilliant tropical colors. It would set off a 28-year long journey of discovery by Ocampo to expand upon this theme, by utilizing a composition of flowing cubistic shapes color-patterned in sharp oranges, canary yellows, shrill reds, deep blues, or tropical greens. Utilizing common Filipino motifs such as fiesta bunting in Fiesta (1957), Ocampo produced richly-brocaded patterns of color-shapes that throb in the visual contrast between warm and cool color, and between round and sharp shapes. His most famous painting was Genesis (1968), an abstract symphony of maroon, red, orange, and yellow that became the design for the curtain drop at the CCP Main Theater.

During the seventies, Ocampo would experiment on this successful formula by producing ever more intricate patterns of shape-color compositions, and produced complex harmonics like his geometric permutations of rock-like shapes in Promenade (1973), or the cyclonic torrent of whirling shapes titled Kasaysayan ng Lahi (1974), a painting which was reproduced into a building facade along EDSA upon the dictate of then-Metro Manila governor Imelda Marcos.

Surprisingly, HR Ocampo was also able to use his geometric abstractions to deal with conventional subjects like Mother and Child (1954), which only goes to show that his vision of Philippine Modern Art wasn’t all apocalyptic alienation-and-gore. Instead, what Filipino artists like Ocampo teach us is that artistic creativity isn’t simply a matter of rearranging visual motifs we learned from someone else. Rather, the disruptions of modern life simply cue us into the real things that matter to us most: a sense of self-identification, purpose, and a need for human togetherness as we collectively face a future full of bleakness with visions of hope.

This article first appeared in BluPrint Volume 4 2010. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

READ MORE: Fusing Old and New: National Artist Benedicto “BenCab” Cabrera