At Helm, dining unfolds as choreography. An open kitchen anchors the room, allowing guests to witness the precision behind its Michelin-starred fine dining menu. Designed by Kevin Nieves of Headroom, the 24-seat restaurant reflects that same discipline in its interior design. Tucked within Ayala Triangle Gardens in Makati, Helm brings together culinary recognition and architectural […]

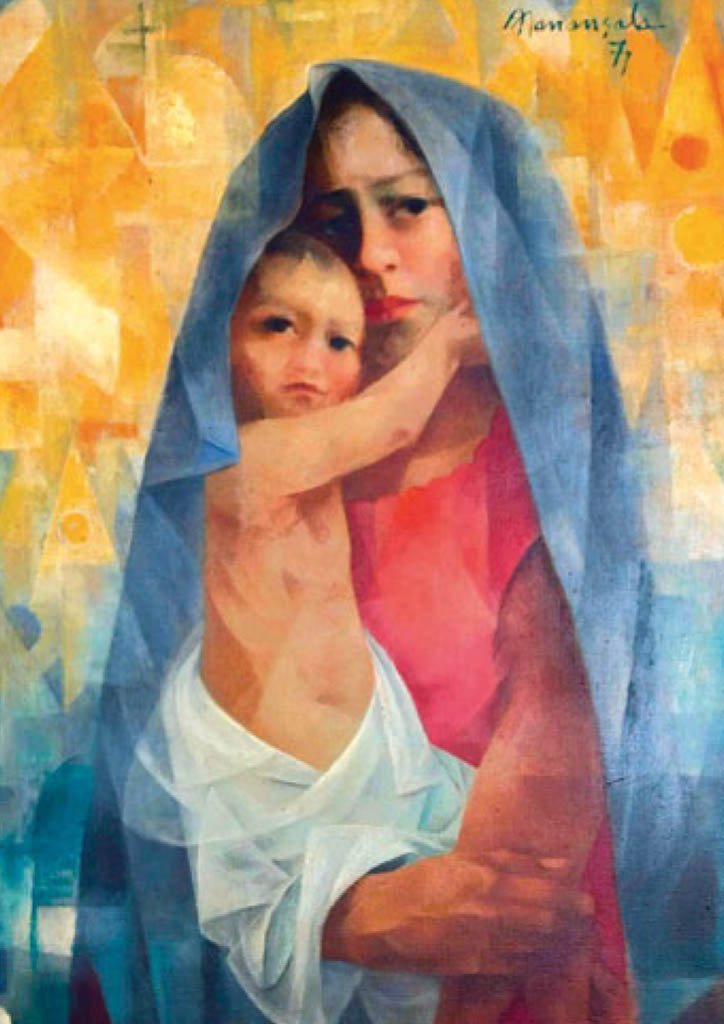

The Genre Works of National Artist Vicente Manansala

Vicente “Mang Enteng” Silva Manansala, posthumously declared National Artist upon his death in 1981, was a remarkable artist and human being of larger-than-life proportions. Manasala was born in Macabebe, Pampanga. A newsboy, golf caddy, and bootblack in his youth, this son of a barber carried the tough street language and garrulous demeanour of his roughneck childhood in pre-War Intramuros well into his sunset years in the seventies, when he was one of the most financially successful artists of his generation. Schooled in the starched-necked ways of the old Araullo public school and the University of the Philippine School of Fine Arts, Enteng could also be charming and famously gallant to women. Although in his early adulthood, he was somewhat of a torpé that it took him eight years of on- and-off courtship to persuade the former Hermenegilda Diaz to be his wife, eloping with her after planting their first kiss during a movie date.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Fusing Old and New: National Artist Benedicto “BenCab” Cabrera

These contradictions of a poverty-stricken childhood and later artistic success in the highest social circles of Manila would impact upon Enteng Manansala’s body of work. Genre includes landscape, still life, portraiture, and depictions of ordinary people in everyday circumstances. In the Philippines, genre first emerged during the late-19th century as the principalia class became dominant through agricultural exports; fomenting the illustrado scholars and intellectuals like Rizal who, educated in Europe, were equal parts political revolutionary and social dandy. Painters from the Academia de Dibujo y Pintura like Lorenzo Guerrero, Justiniano Asuncion, Paz Paterno, and Simon Flores decorated the great bahay na bato with their landscapes, figure paintings, and still lifes. The next generation of painters like Fabian de la Rosa, Fernando Amorsolo, and Victorio Edades in turn magnified genre into the dominant theme in academic painting from the 1900s onward.

Manansala, trained by these maestros in UP, took this romantic formula and brought it into the 20th century by infusing it, first with Social Realism during the early-1940s, and in the early Fifties with the Salon Cubism that he learned firsthand in Paris from Fernand Leger. This entailed the use of cubistic shapes that, instead of shattering the image in the manner of Picasso, delicately defined their masses as a series of decorative planes that overlapped and produced a throbbing, crystalline effect on its subject, so much so that Manansala’s style would later be called Transparent Cubism. His ‘Madonna of the Slums’ is considered one of the key components in modernist art during the 1950s.

Among these genres were the stock images that populated the social space of the Filipino masses during the mid-20th century: the male cockfighter with his prized fighting cock in his arms; the female street vendor with her bilao; mothers carrying their children; women sewing at home or just lounging around; still life arrangements of platefuls of seafood; landscapes full of trees; families gathered over a frugal meal; and the iconic barung-barong shanties that arose out of the devastation of World War II to fill every nook and cranny of Manila.

More than any other Filipino artist in the 20th century, it was Vicente Manansala who mastered these genre subjects using his trademark Transparent Cubism style that he could virtually claim the entire field of Philippine Modern Art in genre for himself. It was due to Manansala’s influence, for example, that other Filipino Modernists started using his style of Cubism (like National Artist Ang Kiukok, who was Manansala’s student at the University of Santo Tomas, and assistant to his various mural projects in the late Fifties); or rode on the waves of popular consumption of his genre subjects from the sixties onward (like Mauro Malang Santos).

This did not mean that Vicente Manansala fawned on his rich clients by flattering them with pretty pictures of the ideal. His first mural commission, the now-lost 1956 masterpiece painted for the National Press Club restaurant, explicitly depicted the machinations of corporate greed in compromising press freedom. His works in the mid-forties were remarkable in their noble depiction of menial labour, especially of fishermen hauling their catch to shore—scenes Manansala was very much part of when he and his young family lived in Masantol, Pampanga, during the Japanese Occupation. Enteng Manansala’s characterization of Filipino folk always had a hard edge to it, a bite of social reality that he ironically shared with his rich clients by indulging them with images of simple, hardworking people that hung in their opulent private spaces, in effect allowing the poor folk to live among the rich by their presence on canvas.

Manansala’s sophisticated style of painting always rendered faces with an economy of brushwork, and yet retained their unique character and pathos. This can be seen in two other contradictory themes Enteng Manansala indulged in—the female nude and the crucified Christ. The first was as a result of his membership in the Saturday Group, when artists banded together during Martial Law to cater to the increasing demand for female nude sketches drawn on the spot. The second was a consequence of his Christian faith. The Crucifixion would be the last subject he painted before he died. In the end, Vicente Silva Manansala stayed true to his working-class roots, but elevated them to the rarefied realms of Modern Art, and in so doing promoted the idea of the simple folk as sophisticated agents of social change.

This article first appeared on BluPrint Volume 4 2010. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

READ MORE: When Worlds Mutate: The Abstractions of National Artist Hernando Ruiz Ocampo