An inside account of The Lion King masks and puppets department

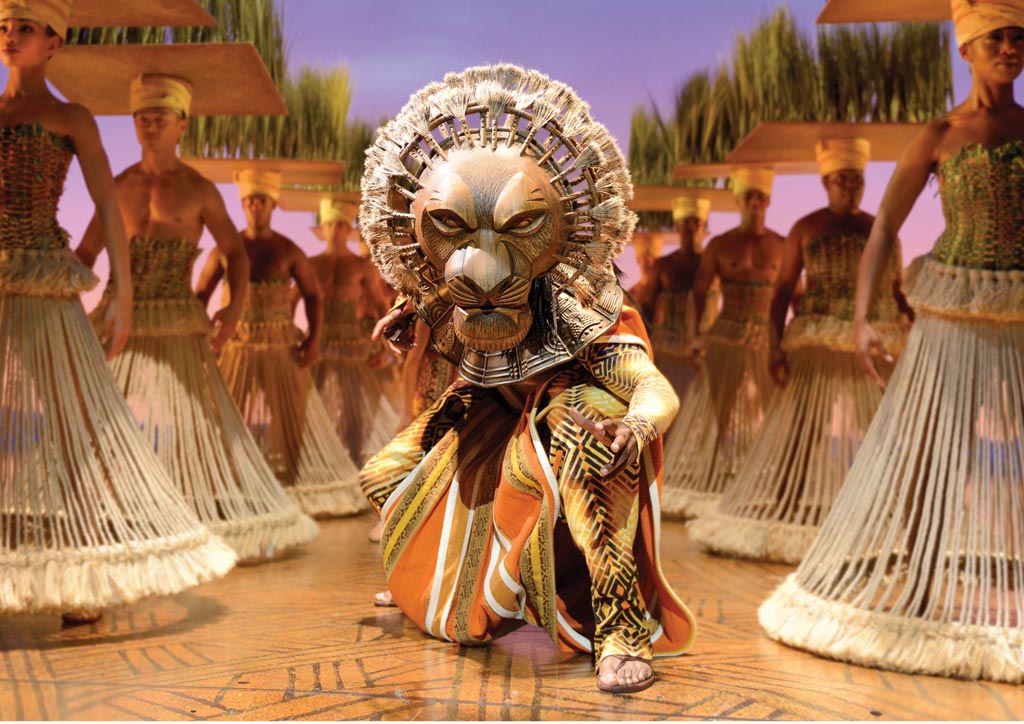

The Lion King puppet design is about the “dual event,” a concept director, designer, and visionary Julie Taymor materialized when she brought Pride Rock to Broadway over twenty years ago. And if you’ve ever seen the musical, you know there’s an alchemy binding the costumes and the actors together.

We visited The Lion King’s puppets and masks workshop for its Manila run to talk to the team sustaining Taymor’s vision onstage. Mike Grimm, on his 17th year with the production, is the Associate Puppet Designer for The Lion King worldwide. Tim Lucas, Head of Masks and Puppets, has been with The Lion King since 2011, through its Singapore and Shanghai runs.

Tell us about where Julie Taymor got inspiration for these puppets, how she worked on them, and her vision for The Lion King.

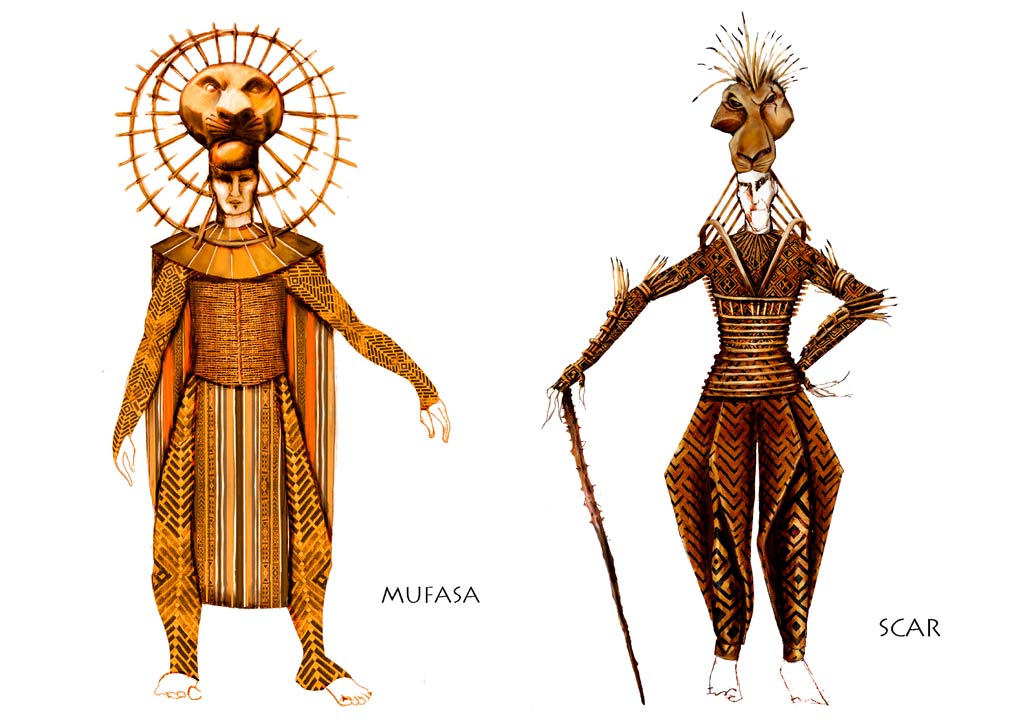

Mike Grimm: Her time in Asia inspired her the most. Before working on The Lion King, she traveled to Japan and lived in Indonesia for a longer period. And that’s where she learned of the puppetry culture in these countries. So when Disney approached, she knew she wanted to do puppets differently by not hiding people inside the animal costumes like mascots. She really wanted the humanity to be apparent because of the story. She wanted the actors to be actors and at the same time animals. That’s what she calls the “dual event.” Nobody’s face is ever hidden by a mask. The mask is, in fact, above the face so we see the actor’s expressions and the mask at the same time. There are two sources for the character. So it’s up to you as an audience member to decide what to look at. And I think that is absolutely brilliant!

How did you get into puppetry? Did you formally study design?

Tim Lucas: I did not study puppetry formally, but I’ve been a fan of it since I was a kid through the marionettes on TV shows like Thunderbirds and Captain Scarlet. My main interest at that time was costumes, which eventually led to puppets. So it was first a hobby then a job. When The Lion King came to Singapore, I thought it would be a good opportunity to try something different.

MG: My background is in prop-building with shows like Cats and Phantom of the Opera. I didn’t know what I wanted to be when I was child but I loved building stuff with my hands, which started with sock puppets then adding arms and sticks. I was also doing some marionettes so there was always an interest in it. Then life brought me from Germany to Italy and back. That was when I started working in theater prop department. There was this German production which involved puppets and I started building them. I remember making a cow head and the director wanted the ears to move and the eyes to twinkle. My involvement is really the technical side of puppetry while the set designers take care of the aesthetics.

So puppet design is an art and it involves engineering too. But it is also very reliant on the human body for motion.

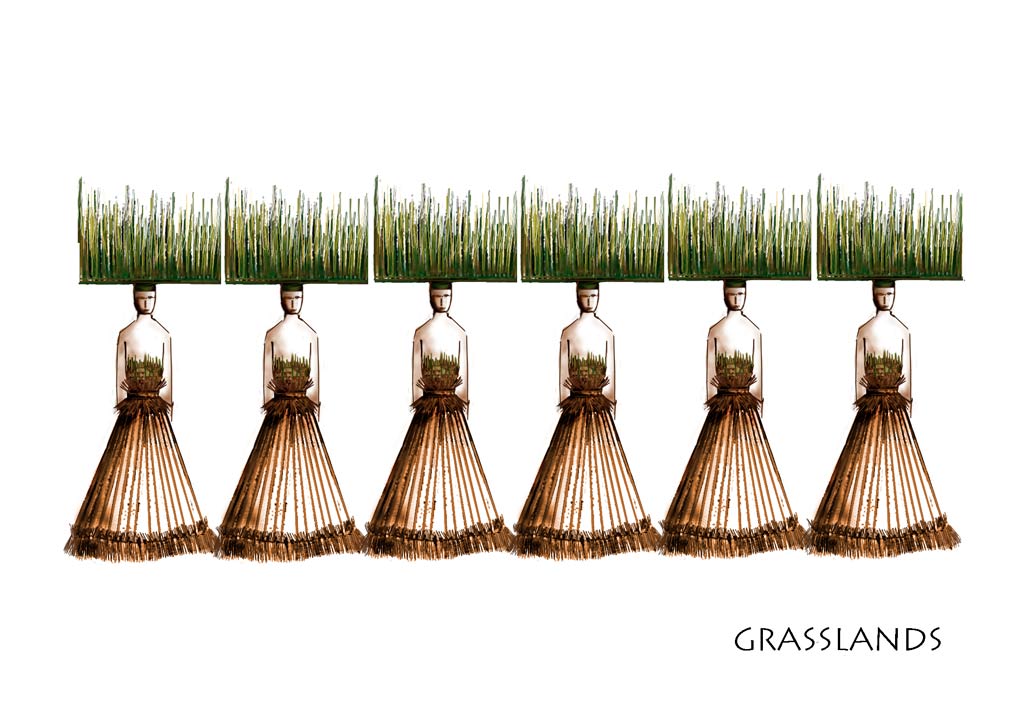

TL: Depending on what the puppet is supposed to do in the production, be it an animal or something non-human, we need to consider the range of human movement. So it’s about looking for a compromise between the ideal vision for the puppet and what our bodies can do in order to create the illusion of an animal onstage.

How many puppets are there all in all?

MG: In total, there are about 235 puppets. But we have props too, bringing the count up to 400 pieces.

Do you classify them? What are the main categories?

MG: Zazu is a classical hand puppet. Timon is completely based on the Japanese bunraku puppet. We have rod puppets, a lot of shadow puppets in the show, and full-body puppets. They are all here.

Have the puppets undergone any alterations or “refreshing” over the 20 years the production has been running?

MG: 20 years is indeed a long time. When they started The Lion King, no one expected it to run forever. The design overall has not changed and it’s in our interest to keep Julie’s vision intact. Materials have changed a lot though.

READ MORE: A Fitting Retrofit: The Restoration of Manila Cathedral

For example, the carbon fiber masks. Were they always made of that material?

MG: Yes, they were always carbon fiber but 20 years ago it was the new thing to do. So when the show started, many could not grasp how Mufasa’s mask (which looks like carved hardwood) could go on someone’s head without breaking his neck.

How small is the smallest puppet? And how big is the biggest one?

TL: The little rat that Scar kills is about 12 cm. And the biggest would be the giraffe.

MG: The “fun” giraffe

There’s a normal giraffe and a “fun” giraffe?

MG: That’s right. There’s a scene where the kids enter a dream. We have a very colorful mise en scene there. The ostriches, giraffes, and other animals look like kids’ drawings. During her design process, Julie asked children to draw animals how they imagined them, which she then translated into these “fun” puppets.

TL: So there are four “fun” giraffes that are about 5.5 meters tall

MG: The biggest animal, however, is the elephant which is 4 meters long, 3.5 meters tall, and 2.5 meters wide.

How many people are in that elephant?

MG: Four. Each leg, one person.

During casting, how do people feel being chosen to play the leg of the elephant? It’s like “Oh, I finally got in The Lion King! Then the anti-climactic punchline: as the elephant’s leg.”

MG: They are alright with it because it’s only one aspect of their work in the performance. The people in the ensemble play multiple roles: an elephant’s leg in The Circle of Life could later be a wildebeest or a gazelle in the savanna.

As someone in charge of the puppets, what’s the most nerve-wrecking scene for you?

TL: Every scene is important. Puppets run through the entire show and it’s what makes The Lion King. If something goes wrong and we can’t fix it, it kills the illusion of the story and the suspension of disbelief. But if I had to choose one, it would be “The Circle of Life” because it sets the stage for everything. If that scene is perfect, everything else will fall into place.

Do you keep spare puppets? What happens when, for example, a leg gets knocked off?

TL: Yes, there are some spares. Depending on the scene, we can do a quick-change or a fast repair on the side of the stage. Get them done. Get them out. It’s almost like a pit stop. Then when the show is over, we take it back to the workshop for major repairs.

MG: There are three people in the puppet department who do all the maintenance and touch-ups during the day. During the show, they don’t do anything watch out for something to break. And there is no one show that nothing breaks. The worst thing that can happen is for a show report to indicate that a show stopped because a puppet could not be fixed in time. So, for example, even if it costs just as much as a car, we keep a spare Zazu puppet so the show can go on. For the Pumba, there is only one. If that breaks, the puppet department needs to exhaust all solutions fast.

Is the storage of puppets similar to the storage of art work?

TL: It’s not as delicate as an art museum where air-conditioning is needed 24/7 but these puppets need ample room. Carbon fiber has a certain life span so an even room temperature will help it last long. And certain materials like thermoplast need to be kept away from heat.

You did not originally design nor create the puppets. Where do you think your creativity as a designer fits into the production?

TL: For my end of the job, it’s more of we handle the fixes in the most efficient way especially when the breaks happen in the middle of shows. No two breaks are exactly the same.

MG: I don’t see myself as a designer here, respecting Julie’s work a lot. It is interesting going around the world. I will hit every production once every year and make sure that the design is aligned with the vision Julie had twenty years ago. And some things tend to stray. If you have not been in the production for a year, you will notice deviations like the fading of color, which needs to be rectified.

For me, it’s a design challenge to keep the original design and bring it back to the stage every single time. There are times when we need to make peoples’ lives easier by changing the structure of the mechanism, which is ok with me. But in terms of the external design, that has to stay intact. ![]()