A Fitting Retrofit: The Restoration of Manila Cathedral

When Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle ascended the cathedra of the Basilica of the Immaculate Conception, popularly known as the Manila Cathedral in Intramuros, one of his first acts was to close down his church. For two years since February 2012, the sculpted cast bronze doors were sealed to pave the way for a much needed restoration, a first since the cathedral’s reconstruction more than fifty years ago. A previous study commissioned by the Manila Metropolitan Cathedral Basilica Foundation (MMCBF) under the leadership of Tagle’s predecessor, Gaudencio Cardinal Rosales, revealed that the Manila Cathedral’s structural integrity had been compromised as evidenced by the cracks on walls and key portions of the structural foundation.

Worried about the safety of the parishioners, Rosales instructed the MMCBF to raise funds and start a major retrofitting of the church. When he retired as Archbishop of Manila in December of 2011, he passed on the responsibility of overseeing the project to Tagle, who, prompted by the devastating effects of the 6.7-magnitude earthquake that hit Negros Oriental two months later, immediately ordered the start of the retrofit.

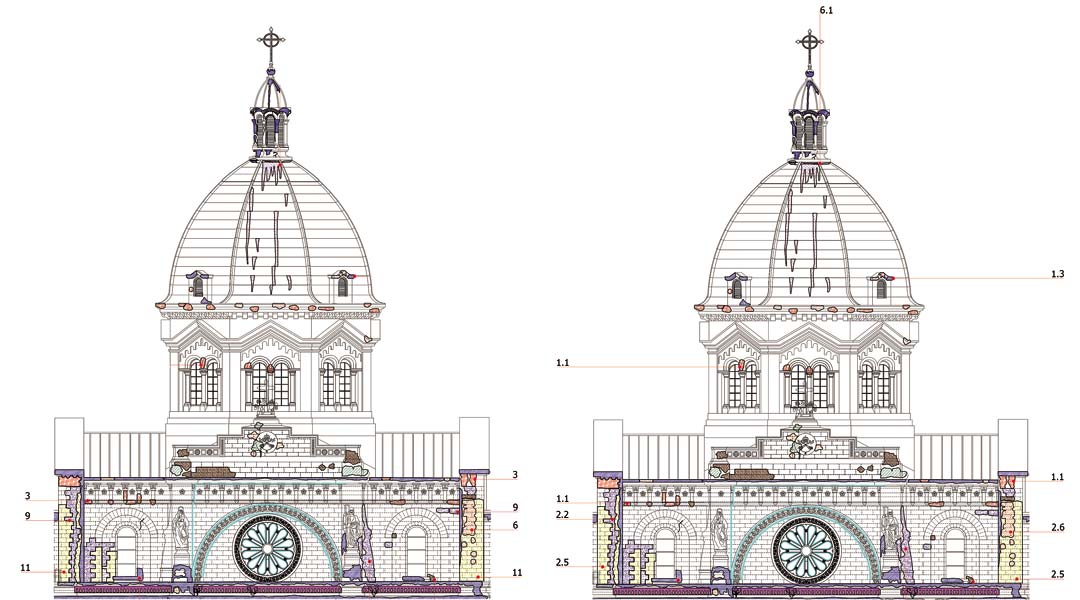

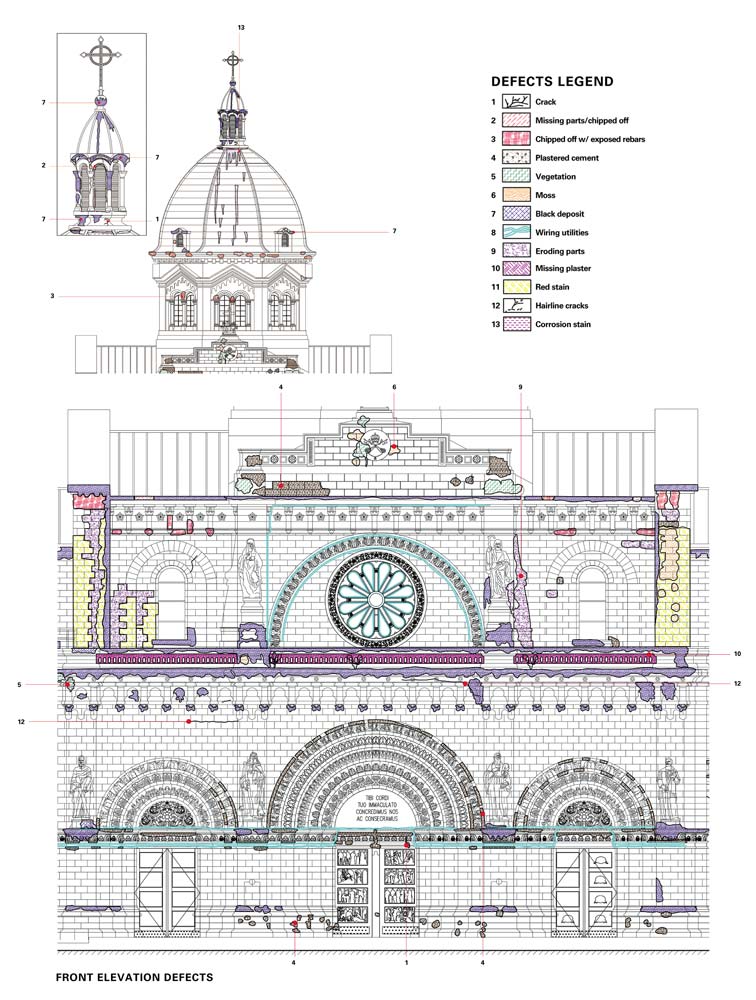

Tropiks Design Studio spearheaded the systematic conservation of the Manila Cathedral. “We studied archival documents from the Arzobispado de Manila, including the original blueprints of the cathedral from the 1950s. We consulted the book, Manila Cathedral, Basilica of the Immaculate Conception, by Ruperto Santos and Maita Reyes. We also studied the structural findings of ALAI,” says Patawaran. To verify the accuracy of the blueprints, they tapped Digiscript to do a high definition 3D scanning of the cathedral to get as-built plans.

READ MORE: High-Tech Hope for Our Heritage: 3D Scanning by Digiscript

Structural conservation

Aside from structural consultants, Tagle rightfully called in architectural conservators. Conservation architect Melvin Patawaran of Tropiks Design Studio affirmed the findings that the concrete materials used in the columns and beams of the cathedral were below the standards prescribed by the 2010 National Structural Code of the Philippines. Visible cracks on the walls were found out to be superficial, caused by the incompatible cement plastered over the adobe or volcanic tuff walls.

Cement plaster has been the bane of many historic churches in the country. Given time, such incompatible cement plaster, which locks in moisture instead of allowing the original porous stones to naturally drain and dry, can severely damage the adobe walls, exposing them to greater risk of collapse during an earthquake. Plaster or palitada is the protective layer of mortar that prevents masonry walls from deteriorating due to exposure to the elements.

A sacrificial layer, plasterwork should never be stronger or more impermeable than the backing surface to which it is applied. Ideally, the cement plaster should have been carefully removed. However, pressed for time and concerned with the more urgent issue of retrofitting the structural columns, Patawaran and his team of material conservators decided to retain the modern cement plaster and provide instead weep or vent holes that supposedly allow moisture to evaporate and the old adobe walls to breathe.

For portions of the wall with exposed adobe, the team applied a fresh coat of compatible porous material. The composite plastering was dyed to match the color of the existing fabric. In every conservation project, it is important to respect the community’s connection and visual recollection of the building being conserved. The lime-washing of the Daraga Church in Albay, for example, caused a stir as most parishioners weren’t informed about the visual effects of the restoration work, thinking that their beloved old church was desecrated with ghastly white paint just to look new.

To strengthen the existing concrete columns, carbon fiber retrofitting was undertaken. Carbon fiber retrofitting is a modern technique wherein strands or sheets of carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP), a high-strength, highly elastic, lightweight, and durable material, are wrapped around existing concrete columns to enhance its shear strength and improve its seismic resistance.

CFRP is stronger than steel and though it is more expensive than traditional steel plates or jackets, the low cost of installation using only epoxy and resin can offset the high cost of the composite material. Because it is lightweight, it does not impose an additional load on the structure. Installing the carbon fiber proved to be a challenge for the Manila Cathedral. Marble installation experts had to temporarily remove the heavy pedestals made of Carrara marble and take down the marble claddings of all the columns inside the cathedral. The vertical members had to be fully wrapped with CFRP from top to the bottom, hence some of the decorative Corinthian capitals and elaborate moldings along the arches needed to be sacrificed.

The team hired the House of Precast to make casts of the capitals and moldings, which were used to produce replicas to replace the originals. After the carbon fiber wraps had been installed on the columns, the marble cladding were restored carefully without damage. Roof beams were likewise retrofitted using structural steel.

Another major problem was the constant flooding inside the church. The conservation team traced the cause of flooding to a clogged storm water drainage system. They carefully took off the marble flooring and constructed a new and larger drainage system underneath to prevent storm water from damaging the foundations. After installing the drainage system and fixing the electrical and sanitary lines, the marble floor pieces were reinstalled piece by piece, cleaned, and polished.

Upon investigation, the conservation team also arrived at a disturbing finding. The soil upon which the cathedral was built is weak and soft, and prone to liquefaction in stress conditions brought about by an earthquake. Efforts to reinforce the structural integrity of the cathedral would be for naught if this issue were not addressed. To stabilize the soil, the team injected grouting cement into the soil mass. When applied under pressure, the grouting solution acts as a stabilizing agent that reacts with the soil and forms a firm and stable mass. This finding is a reminder to all conservators to look beyond the building itself, and examine as well the ground it is built on, and its environs.

Aesthetic unity

The restoration work has been largely structural, but when the Manila Cathedral finally reopened its doors two years later, the parishioners noticed many visible improvements. The adobe walls were cleaned of stains, mold, and deposits, and certain portions were re-plastered with fresh and compatible mortar. Harmful plants that grew on the façade were cut up to the roots, and chipped off portions of architectural elements were repaired. The most striking improvement is the new lighting system designed by lighting consultant PL Light in Existence. Lighting creates different moods and helps produce a powerful ambiance that allows the parishioners to better appreciate and experience the liturgy as it unfolds. Furthermore, a new audio-visual system was installed to facilitate communication and comprehension.

The project team respected the historical significance of the Manila Cathedral and adopted a conservation methodology that imposes the least intervention upon the building’s fabric. They opted to preserve the cathedral following the original design intent of Fernando Ocampo in 1958 and removed all incompatible additions such as rooms and offices that were irresponsibly attached to the building. To make sure the cathedral would withstand the next big earthquake, the team rightfully turned their attention to retrofitting the structural components of the cathedral before addressing aesthetic and beautification concerns.

The goal was ever clear: to restore the cathedral to a state most of our parents and grandparents today would remember it and to create a better physical setting to celebrate the liturgy. We fervently hope other churches would follow in the footsteps of the ecclesia caput et mater omnium ecclesiarum—the head and mother church of all churches in the Philippines. ![]()

READ MORE: Iloilo’s Calle Réal shows Escolta how heritage CBD restoration is done

The conservation plan of the Manila Cathedral called for a thorough assessment and analysis of present defects that needed to be addressed. In this drawing of the church’s façade, the blue marks represent black deposits on the walls. Cyan marks represent existing utility lines. Marks in magenta represent missing exposed masonry units with missing plasters. Red marks represent chipped off portions and exposed rebars. The yellow marks are red stains or deposits. Drawings courtesy of Tropiks Design Studio.

Design Team

Proponent: Manila Metropolitan Cathedral Basilica Foundation

Architectural Conservation Consultant: Melvin Patawaran of Tropiks Design Studio

Materials Conservation Consultant: Prof. Maita Reyes and engineer Terry Malicse

Structural Consultant: Angel Lazaro Associates International (ALAI)

Lighting Consultant: PL Light in Existence Co.

Project Manager: SP Castro

Contractor: DM Consunji

This story first appeared in BluPrint Volume 5, 2016. Edits were made for Bluprint.ph.