Tunnel Vision: Fort Bonfacio War Tunnel Restoration

“When you descend, it should feel like you have been transported to a 1940s military facility,” says architect Joel Vivero Rico, describing his restoration plans for the secret tunnel General Douglas MacArthur ordered built 75 years ago in Fort McKinley, now part of Bonifacio Global City. Owned by the Bases Conversion Development Authority (BCDA), the tunnel will be converted into a museum, with the Tourism Infrastructure and Enterprise Zone Authority (TIEZA) funding the adaptive restoration effort, and the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) funding the museum content.

“There will be over 20 galleries, including a war room, a map room, a communications room, an ammunitions room, and an office for MacArthur. Aside from the period military equipment and fixtures, music from the early 1940s, as well as recordings of MacArthur addressing the troops, will be playing in the background, interrupted by radio communications and the rumble of distant bombing. We’re even thinking of bits of grit falling from the tunnel ceiling when the bomb blast sounds like it is directly overhead. We want it to be authentic and fully experiential.”

There are conflicting histories of the tunnel. Some say the excavation started in 1941, others say 1936, and others still, insist the digging started much earlier. Rico spent over a year burrowing into the tunnel’s provenance and history, poring through books, journals, reports, and documents about World War II, including unpublished memoirs of officers and men who took part in digging the tunnel. What follows is Rico’s account, which he hopes will come to life when visitors experience the once secret, subterranean passageway.

READ MORE: Digiscript’s High-Tech 3D Scans of Philippine Heritage

Fort William McKinley

After the Philippine-American War in 1898, the US forces established their army headquarters amidst the vast lands of Macati, along the banks of the Pasig River. Administered by Gen. Leonard Wood in 1907, it was named in honor of the president of the United States of America. By the 1920s, Fort McKinley housed the US Army headquarters and barracks, a hospital, a bakery, a post exchange, a chapel, a luxuriously appointed officers’ clubhouse, recreational facilities, a polo field, and more. Some of the troops based in the camp were members of the Philippine Scouts, and they lived in the area known today as EMBO, or Enlisted Men’s Barrio.

In early 1941, news of the growth in military power of the Japanese Imperial Army led General Douglas MacArthur, commanding general of the US Forces based in Fort McKinley, to order the construction of an air warning service tunnel at the back of the US Army Commanding General Headquarters. He wanted it to house a communications and command center that would serve as the unseen central defense of Philippine skies. The idea was spies and coast watchers in various parts of the country would spot incoming Japanese planes and track their locations continuously, while relaying the information to the underground HQ via radar sets.

Sakura Heiei

War broke out, however, on December 7, 1941, with the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The American were caught flatfooted, and within a month, Japanese forces occupied Manila, taking over Fort McKinley on the evening of January 2, 1942. Under Japanese command, the base was renamed Sakura Heiei (Cherry Blossom Barracks). The tunnel was enlarged to hold barracks and store artillery ammunition supplies, with entrances and exits added for easier access. In 1944, Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi, who led the Japanese Naval Defense Force in Manila, moved his command center to the tunnel. On February 3, 1945, American and Filipino forces descended upon Manila from different directions, and for one month, in what is now known as the Battle of Manila, engaged the Japanese in the most destructive and bloody urban combat to take place in the Pacific theater of war. According to unconfirmed reports, Japanese officers, along with an entire regiment of soldiers inside the tunnel, survived the ferocious bombing by Americans of Manila and surrounding military installations. However, it was in the tunnel they would meet with fiery deaths, torched by Americans who knew of its existence.

Fort Andres Bonifacio

On July 24, 1949, the American government officially turned over the fort complex to the Armed Forces of the Philippines. The AFP initially planned to use McKinley as their HQ, which they later established as Camp Aguinaldo in Quezon City, instead. On June 19, 1965, by Republic Act 4443, Fort McKinley was renamed after the revolutionary leader and first (though unofficial) president of the Philippines, Andres Bonifacio. It became the headquarters of the Philippine Army Command and Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC). Portions of the camp became the bases of the Philippine Navy, the Joint US Military Advisory Group (JUSMAG), and the Philippine Marine Corps. A portion was allocated to the AFP Veterans Housing Projects, while sections were set apart for the US War Cemetery and Libingan ng mga Bayani. In the mid-1970s, Major General Fortunato Abat, Commanding General of the Philippine Army, ordered the cementing and rehabilitation of part of the tunnel by the 51st Engineering Brigade.

In the 1980s, Major General Mariano Adalem ordered the conversion of the old US Army Commanding General Headquarters into the Philippine Army Museum and Library, with the tunnel as an integral part of the museum experience. The museum and the tunnel were inaugurated in 1989, with the defense press corps as the first group of visitors.

During the attempted 1986 military uprising against the dictator president Ferdinand Marcos, the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), led by Army Col. Gregorio Honasan, used the tunnel as their barracks and command post between January to February 1986. The revolt was coopted when hundreds of thousands of civilians converged at Camps Crame and Aguinaldo to protect the rebel soldiers from being attacked by forces loyal to Marcos, and thus the peaceful People Power Revolution led to the ouster of the dictator.

Bonifacio Global City (BGC)

In 1995, president Fidel Ramos signed Republic Act 7227, creating the Bases Conversion Development Authority (BCDA) to oversee the transformation of military bases to civilian use. Subsequently, the area formerly known as Fort McKinley, Sakura Heiei, and Fort Bonifacio became known as Bonifacio Global City—a progressive and modern mixed-use complex of office, commercial, and residential buildings, run by the consortium led by Metro Pacific called Bonifacio Land Development Corporation. Parts of the old fort areas, however, are still maintained by the AFP.

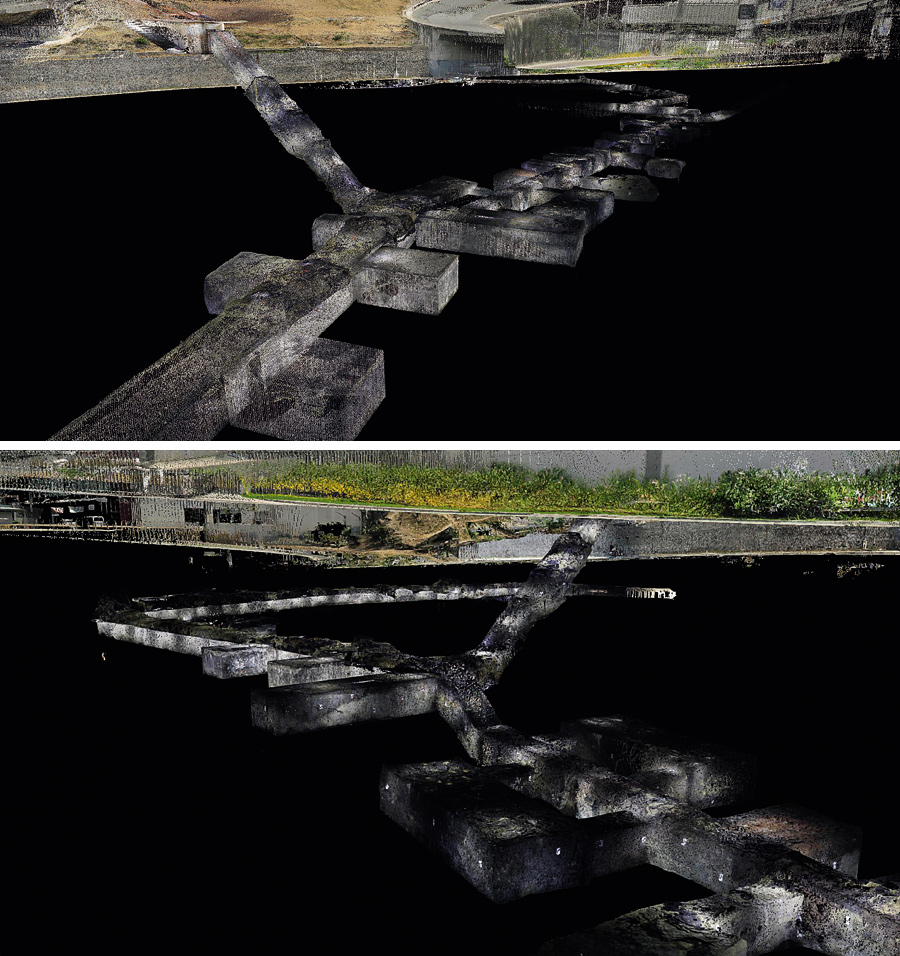

In 2013, the BCDA, AFP, NHCP and National Museum of the Philippines signed an MOU to restore and reuse the Bonifacio War Tunnel as a museum for the 21st century. The project was opened to bidding, and in 2015, BCDA president Ariel Casanova named Philipp’s Technical Consultants Corporation (PTCC) as the winning contractor. Among the consultants PTCC brought in for the initial phase of the project were Digiscript, specialists in digital mapping to survey every square inch of the tunnel, and architect Joel Rico, to serve as restoration architect and design the museum experience.

Back to the present

Just going down the 76 steps to reach the first tunnel 17.47 meters below ground level is an experience in itself. The 42-degree slope appears steeper than it is. In the absence of handrails, with only flashlights to help us see our way (vandals had stripped away everything they could), and with the treads slick from three days of heavy rain prior to our visit, we made our way down slowly, cautiously, and at a crouch, for fear of toppling headlong down the stairs.

No doubt the stairs will be easier to navigate when repaired, but it will still be potentially hazardous as there are only two landings to break a fall—one at 2.73 meters below ground level, and the other at 13.05 meters.

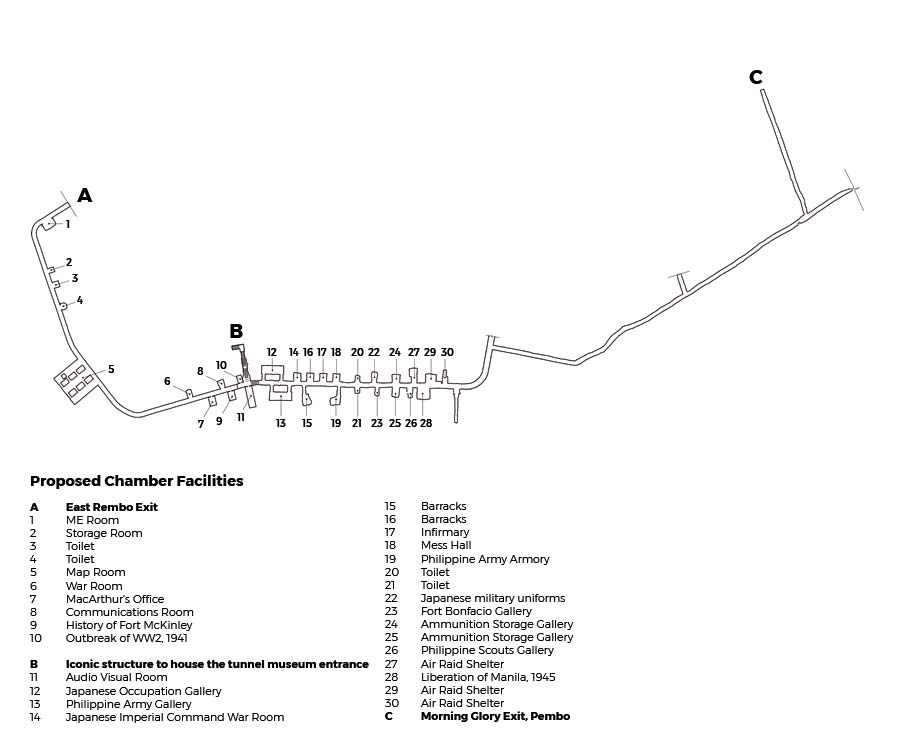

Using the stairs as the entrance to the museum presents another problem, which is managing the flow of people touring the tunnel. The stairway divides the tunnel into two parts. Descending the stairs and turning right takes you to the section of the tunnel dug by the Americans, about 230 meters long, with 11 chambers. Turning left from the stairway takes you to another flight of steps going down 3 meters, to the tunnel dug by the Japanese, which is about four times as long as the American side, and has 19 chambers.

On average, the tunnel width is 3 meters, with portions only 2.2 meters wide. In order to see all the exhibits in the different chambers, visitors would have to retrace their steps after seeing the American side, cross over to the Japanese segment of the tunnel, and then double back towards the stairs, where they will climb the 76 steps back up to the present time.

A more practical option would be for visitors to enter from one end of the tunnel and to exit at the other end. They could enter the American tunnel at an opening along 27th Avenue in Barangay East Rembo, Taguig, and then exit from the Japanese tunnel near Morning Glory Street in Barangay Pembo. The sticking point, Rico says, is Barangay Pembo is not under the jurisdiction of the BCDA or of Taguig City, but Makati City. The situation, he says, calls into question the authority of the BCDA to develop property that doesn’t belong to it. Surely the authorities can negotiate an equitable arrangement with Pembo. The barangay is a depressed area that stands to benefit, not only from the sprucing up of the surrounds for the sake of the museum goers exiting the tunnel but also from the sale of souvenirs and refreshments to the visitors. It is hoped that under the newly installed administration of Rodrigo Duterte, and whoever he appoints as the new BCDA president, the politicking and territorial dispute will come to a end and reason will prevail.

That said, it is unlikely the BCDA, TIEZA and NHCP will forego the stairway as the museum’s main entrance—the dramatic descent is the most memorable part of the tunnel experience. According to Rico, when the BCDA had the tunnel restoration bid out, there wasn’t much of a brief to go on. “They knew little about the tunnel; it was up to us to propose how to fix it and what to put in it.” They were clear baout one requirement, though: that there should be an iconic structure atop the tunnel stairway to serve as a war memorial and mark the entrance to

the museum.

The would-be location of the iconic structure is awkward and inaccessible, however. It is the tiny triangular plot of land wedged between the two branches of 32nd Street as it splits then merges with Carlos P. Garcia Avenue (or C5). Because the plot is bound on all three sides by busy streets with fast moving vehicles, Rico’s solution is for people to access the war memorial structure via a footbridge from the top of the five-storey parking building of Market! Market!

According to Rico, based on his, Digiscript’s and PTCC’s study and plan of action, the restoration, museum design, and iconic structure could be completed in two years’ time. As far as he knows, the BCDA gave the greenlight for the “other necessary requirements” in early 2016, and funding from TIEZA is available. What are we waiting for?

Much more important than the museum project seeing the light of day is getting the tunnel complex to be recognized and protected as a site of historical significance. There are conflicting reports regarding the tunnel’s original length. Some say it was 2.4 kilometers long. Others say it was only 1.5. We would all know its full length, and the tunnel would have been in much better condition today if the government had given the Philippine Army Museum and the tunnel, inaugurated by General Adalem back in 1989, its due respect. What we know for sure is that much of the tunnel has been destroyed by the construction boom in the BGC of the past two decades. (Who knows what else was destroyed by the development of Makati City?) According to the BCDA, only 730 meters of the original tunnel “remain unaffected by the development of Fort Bonifacio as of 2013.” As with much of our natural and built heritage, this grievous loss was caused by tunnel vision. In the wheeling and dealing to create and develop Bonifacio Global City, the sellers, buyers and middlemen focused on the single goal of making money, to the exclusion of conserving our inheritance—the nation’s treasure now destroyed and buried forever. ![]()

This story first appeared in BluPrint Volume 4, 2016. Edits were made for Bluprint online.

Photographed by Ed Simon