The Bayleaf – from rundown building to four-star hotel

Much of Manila, including its historical center called Intramuros, was destroyed during the Second World War. Many of the partially damaged buildings like the Manila Cathedral, the City Hall, the Metropolitan Theater, and the Post Office Building were restored and survive to this day, which give the city a certain Old World charm not found anywhere else in the metropolis.

Unfortunately, many old architectural gems couldn’t survive late 20th and early 21st century progress. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the Jai Alai Building and the Paco Train Station were demolished to give way to a new Hall of Justice and a mall, respectively, both of which have not yet materialized. As a consolation, the Paco Train Station’s façade still stands in ruins. Locsin’s Benguet Center in Pasig and Zaragosa’s Union Church in Makati have been torn down for new buildings. 2015 is the year the historic Admiral Hotel’s turn to go down for new development.

So is demolition of old buildings the only solution for progress?

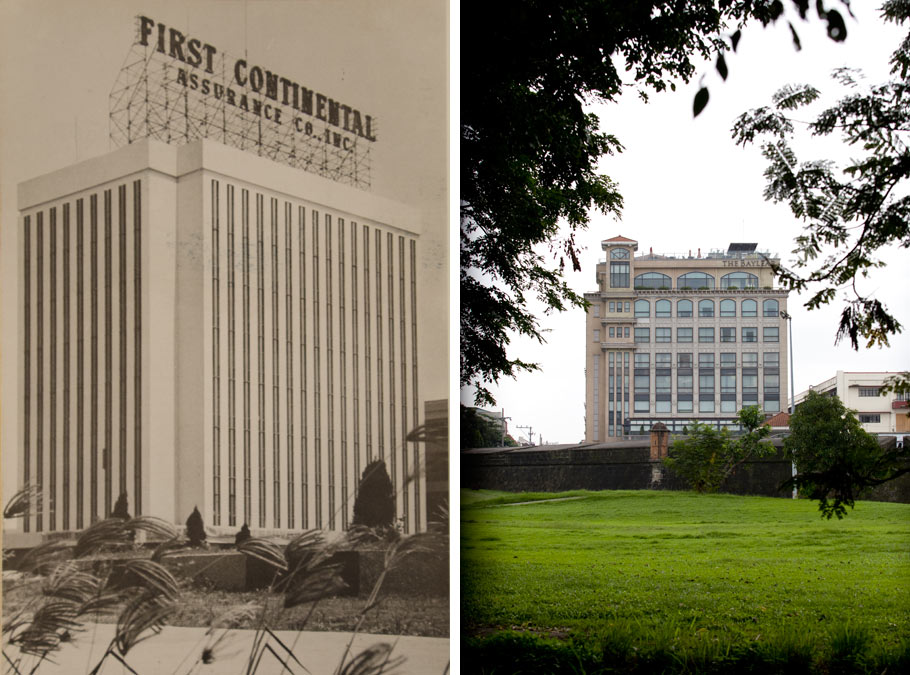

Adaptive Reuse: From First Continental to The Bayleaf

A hotel in Intramuros, ironically, may provide a better solution for the future of old buildings. The adaptive reuse strategy for The Bayleaf should be considered by building owners and architects before demolition. It is a nine-storey hotel within the walled city that has 52 guest rooms, a ballroom, four function rooms, a coffee shop, two restaurants, and a bar at its roof deck. Unbeknownst to many, the building was originally a 1968 modernist office building designed by the late architect Gabriel Formoso. A modern building in Intramuros? How can that be?

The First Continental Assurance Co. Building (later renamed as the Licaros Building) was an eight-storey office building with a façade composed of thin floor-to-ceiling glass windows alternating with pre-cast concrete panels at the corner of Calle Victoria and Muralla, right next to the Mapua Institute of Technology. It is the second tallest building in Intramuros, next only to the Manila Cathedral. Back then, the rules requiring structures within Intramuros to conform with the low Spanish Colonial architecture were not yet in place.

The Intramuros Administration (IA) was created in 1979 by then President Ferdinand Marcos with Presidential Decree 1616 giving the agency the authority on the area’s restoration, development and promotion. The IA’s Design Guidelines dictate that all structures to be built or renovated should follow the Spanish Colonial style of the 1890s with height restrictions in the hopes of recreating the old city’s glorious past.

By 2007, the Licaros building stood dilapidated and abandoned (except for the ground floor which still had a bank for a tenant). The basement was flooded, glass window panes were broken and the frames rusting. It was an eyesore in Intramuros, a perfect candidate for demolition. But it had an ace up its sleeve, which the owners of the Lyceum of the Philippines University (LPU) saw: its height. Because of the IA’s regulations, no building taller than three or four storeys can be built within the walls. LPU, with its main campus only a block away from the Licaros building, saw its potential and bought the property with the intention of converting it into a hotel where students of their Hotel and Restaurant Management (HRM) course could train.

READ MORE: Art Deco Laperal Apartments retrofitted, now a student dorm

During a meeting discussing the construction of LPU’s Cavite Campus with Architect Topy Vasquez, LPU President Roberto Laurel mentioned the property they were eyeing in Manila. A few months later, T.I. Vasquez Architects & Planners (TVAP) was commissioned to design LPU’s hotel and culinary institute.

Design Challenges

Trying to fit a hotel into an old office building is difficult enough as it is. Adding to the challenge is the building’s historic location. TVAP had to design the 1960s modern façade into an even older looking building.

One scheme had a Spanish Colonial base to match the old walls and a completely reflective glass-clad hotel to reflect the sky and make the building’s mass sort of disappear. Another scheme had an unabashedly Spanish Colonial architecture from top to bottom. The architects asked themselves if this was the right approach even if it did conform to the IA rules. But trying to force 19th century design into an eight-storey building was an awful stretch in faking architecture, even if we were in the heydays of Post-Modernism. And nobody really wants a fake of anything.

But trying to force 19th century design into an eight-storey building was an awful stretch in faking architecture, even if we were in the heydays of Post-Modernism. And nobody really wants a fake of anything.

The owner and the architects agreed on a third scheme: a middle ground between the two schemes. A façade of arches, balustrades, clay tiled roof, and lots of moldings to conform with the regulations, but with large reflective glass windows to give the building a modern touch. The large windows also give the interiors some of the most spectacular views of Manila. After a review from the IA, the architects were instructed to apply a few more moldings on the façade based on a book from the agency.

To pay homage to LPU’s main campus design, a ‘tower’ was incorporated on the front corner of the building just by adding a small room at the roof deck and changing the windows down the façade. One good thing about this project is that even though it is located in a historical district, the original façade was out of place in its vicinity that modifying it didn’t result in protests from heritage advocates.

With the columns designed for office planning already in place, the architects had to fit the hotel rooms as best they could. And with the existing front of the building slightly skewed from the perpendicular, each of the rooms varied in area. The interior designers selected furniture with sleek profiles and used mirrors to maximize the visual space. Although the guest rooms were a bit smaller than regular hotel rooms, the owners and designers compensated with the richness of the finishes and fixtures.

As the owners saw the magnificent views from the highest part of the building where one can see the skylines of Binondo, Quezon City, Pasig, Makati and Manila all from the same spot, they asked the architects to design a restaurant and a bar on top. The IA would not allow an increase in the building’s height, so an additional floor was created in the space occupied by the old G.I. roof and its trusses that were hidden behind the building’s concrete parapet. Using this space created an extra floor for the 9 Spoons restaurant and the Sky Deck Bar above it, offering guests one of the best vistas in Manila.

Structural Retrofitting

One of the major concerns during the design of the building was its structural integrity. The structural engineers required and performed tests on the existing concrete columns, beams and slabs to determine their strength and how much reinforcement was needed to keep them within to modern safety standards. The initial design called for chipping and re-applying of additional concrete around the existing structural members.

However, as the construction was about to start, the contractor proposed a different approach to strengthen the building while saving significant cost and time. They proposed a steel plate jacket around the columns and beams instead of adding new concrete. With a guaranteed savings in time and money, the owner and the design team agreed with the proposal. Some additional steel beams also made the ceilings lower than the ideal, especially for the ballroom.

To correct this, recessed ceilings were incorporated in the design as much as possible to compensate for the areas with low beams. To allow for a bigger ballroom, a couple of the existing columns also had to be retained in the middle of the room, which requires some creativity from the hotel managers in the layout of their parties.

Rewards

After almost three years in operation, the extra cost for retrofitting the structure, compromising with some of the spaces and complying with the IA regulations, The Bayleaf has proven to be a worthy investment. The hotel has been ranking on top of surveys and bookings. Occupancy is high and the restaurant and bar are always booked that TVAP was asked to design another restaurant at the third floor deck—the Rafaeli—just two years after the hotel’s opening. TV and movie producers are asking the hotel management for time to shoot some scenes. The architects even received a call from a lady who identified herself as the former owner of the Licaros admitting they didn’t see the building’s potential before selling the property.

With sustainable design being the current buzz word in the architecture and design industry, adaptive reuse for old buildings may well find its way to the building owners’ and developers’ board rooms, too. Existing buildings already have stored energy and materials in them and demolition will definitely use even more energy and resources prior to the construction of the new project.

As Richard Moe, President of the National Trust for Historic Preservation of the United States, puts it: “The bottom line is that the greenest building is one that already exists.” And this strategy should hopefully help the cause for architectural heritage conservation. ![]()

This story first appeared in BluPrint Volume 1, 2015. Edits were made for Bluprint.ph.