Beyond brick and mortar, homes possess a hidden soul—the ability to morph into living narratives. They are silent witnesses to the lives of their inhabitants. Such is the case of fashion stylist Michelle Hui Lao’s home, a dynamic space that reminds her and her son of the changes they have encountered in various stages of […]

Pwera Usog is one of the new art exhibits showing at Gravity Art Space. Available for viewing from May 3 to June 1, it includes the works from a variety of different artists such as Margaux Blas, Anjo Bolardo, Sarah Conanan, Telle de Leon, and others.

The exhibit’s theme revolves around the idea of depicting each artist’s survival from the darker sides of the art world. In the write-up accompanying the exhibit, the writer calls the works a way to “mark their exodus to freedom by creating portents and protective spells against the malevolent gaze of the art scene.”

Specifics are not offered as to what the artists suffered. But they do share stories of every entertainment industry’s exploitative nature already so common in our cultural fabric. From The Valley of the Dolls to A Star is Born, the knowledge that these artists probably encountered unflattering incidents in the past is unfortunately not hard to believe.

And yet, the purpose of this exhibit is not necessarily one of lament, but of learning and reflection. The artists come together to create works that exorcise the experiences while crafting a potential community together that pushes away from the exploitative natures of the industry as a whole.

“A lone crow is regarded as an omen of death and sorrow,” the write-up states. “Flocked together, however, they spark a kind of joy coupled with wistful optimism.”

Do You Know the Way?

Much of the art for Pwera Usog partakes in utilizing religious imagery in radical ways. These artworks personalize these religious figures in ways that can either be irreverent or solemn. Put together, however, they collectively deal with how faith can be exploited as a way of oppressing the needy and the marginalized.

“Babailan” by Laura Abejo, for example, contains a glorious religious figure in the vein of the Catholic Mother Mary sitting in a throne and looking down at the Heavens. Below her, an indigenous woman hugs her baby tightly as they run away from a burning house in the distance.

The beauty and majesty surrounding Mary and her bored expression as she looks down from the Heavens comments on how these symbols of faith rarely are able to help the people who are in need of them. These people are always on their own, and nobody in the throne room will be helping them escape or ascend.

The Breeding of Desperation

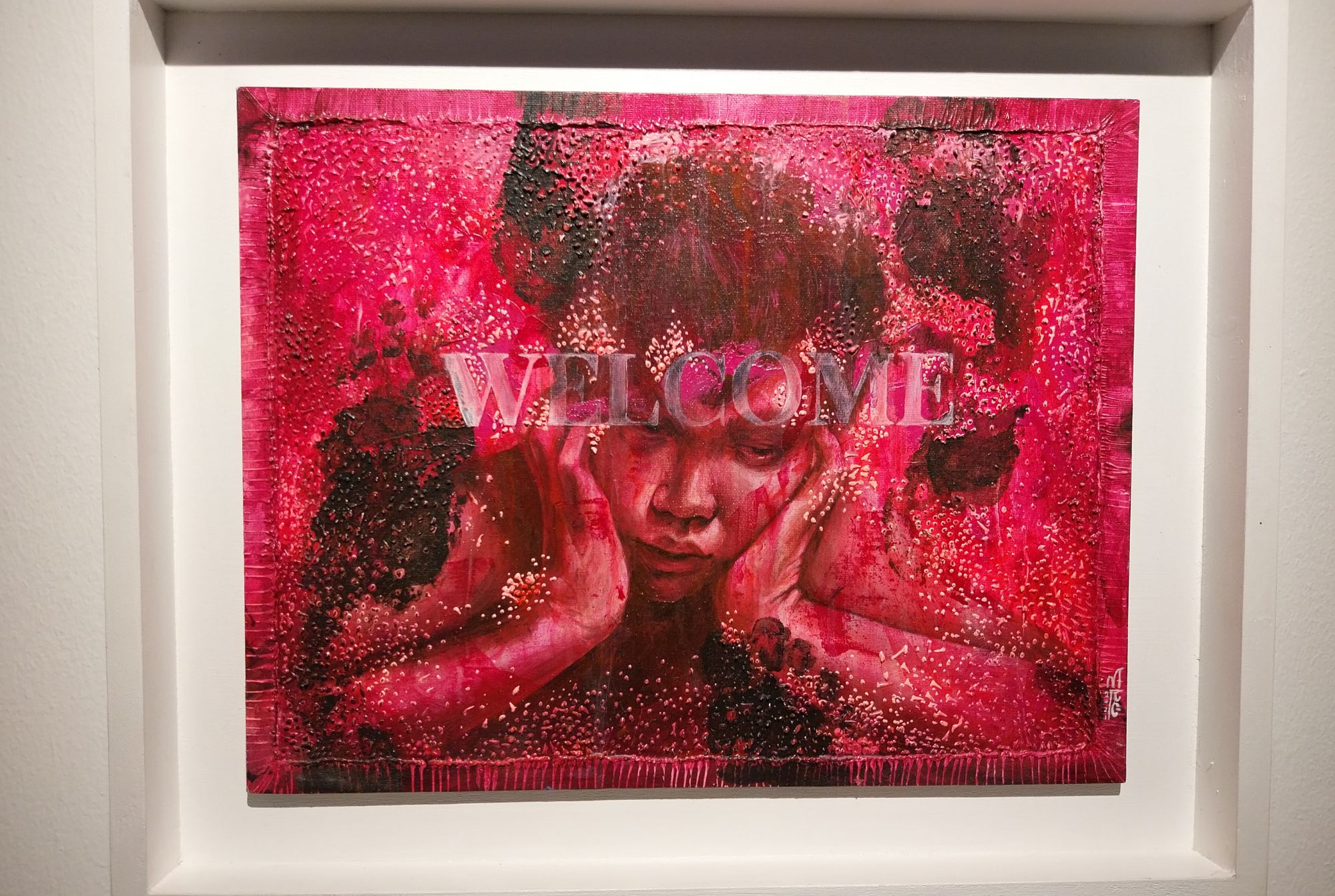

Other works like Marco Tabamo’s “Pispisan ATBP” or Manuel Gomez’s black-and-white painting “17/45” shows the victims and the helplessness they endure within the system. “Pispisan ATBP” has a child’s pensive expression as the outlines of a bloodied welcome mat seems to surround them. “17/45” goes for something even starker: a fetus-like being seemingly watching its own violation in front of them.

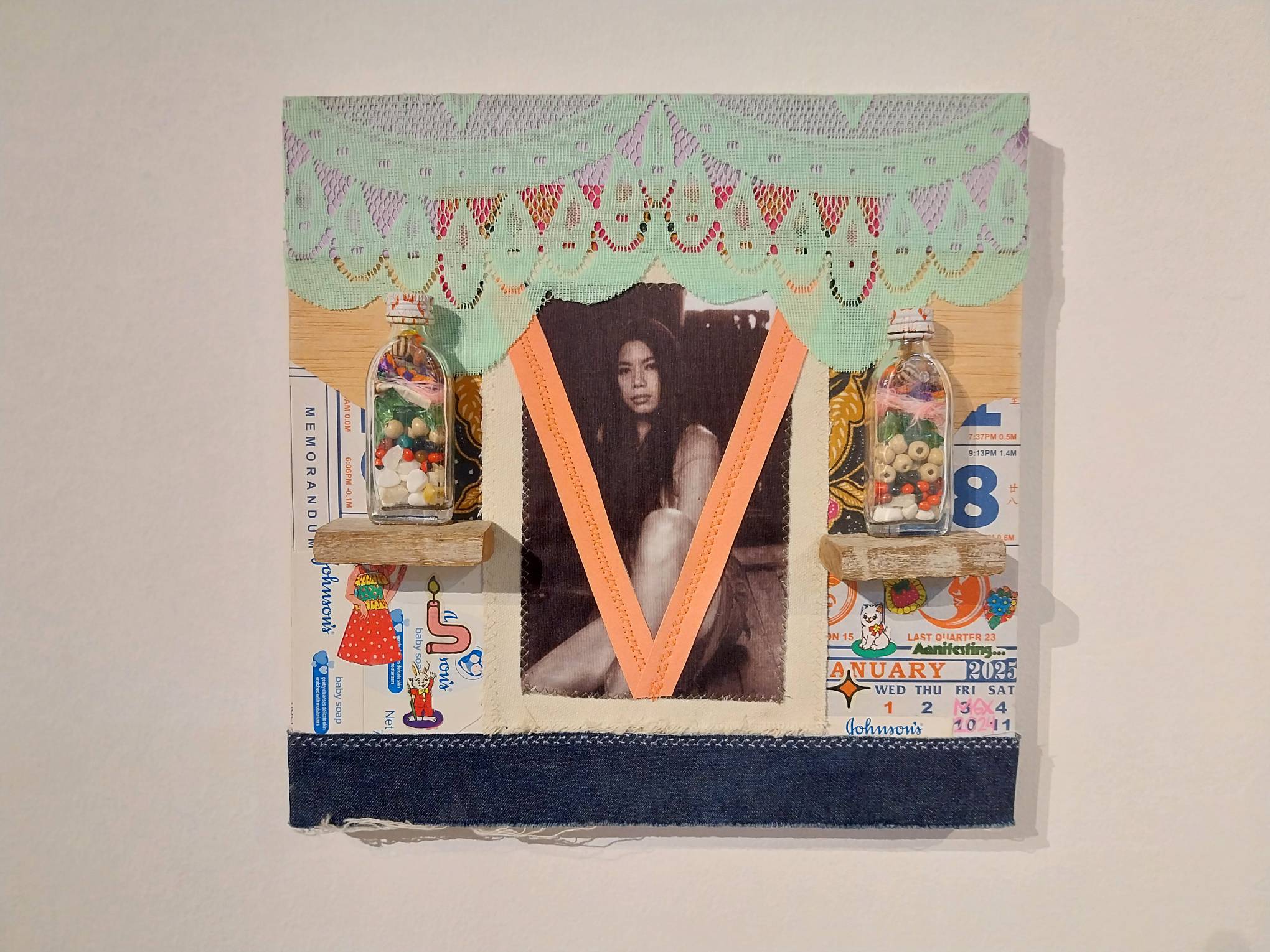

Margaux Blas’ mixed media collages appear to accomplish similar subversive discussions of the effect of society’s hypocrisy. Works like “Excommuni-gago” or “The Lord Knows I’m a Voodootz Child” shows its use in everyday life—but more importantly, the implication that these methods don’t work, that the exploitation of artists and workers in general will continue no matter what.

Removing the Sword of Damocles

Of course, the potential exploitation and degradation of their art constantly hangs on the head of every artist in the world. As a capitalist society, coercion to allow yourself to be exploited is intrinsically part of the system. You either play the game as dictated, or you don’t get to pay your bills.

Thus, Pwera Usog as an exhibit also contains different artworks whose purpose is to keep evil away—a safe space, if you will, where art can flourish without worry.

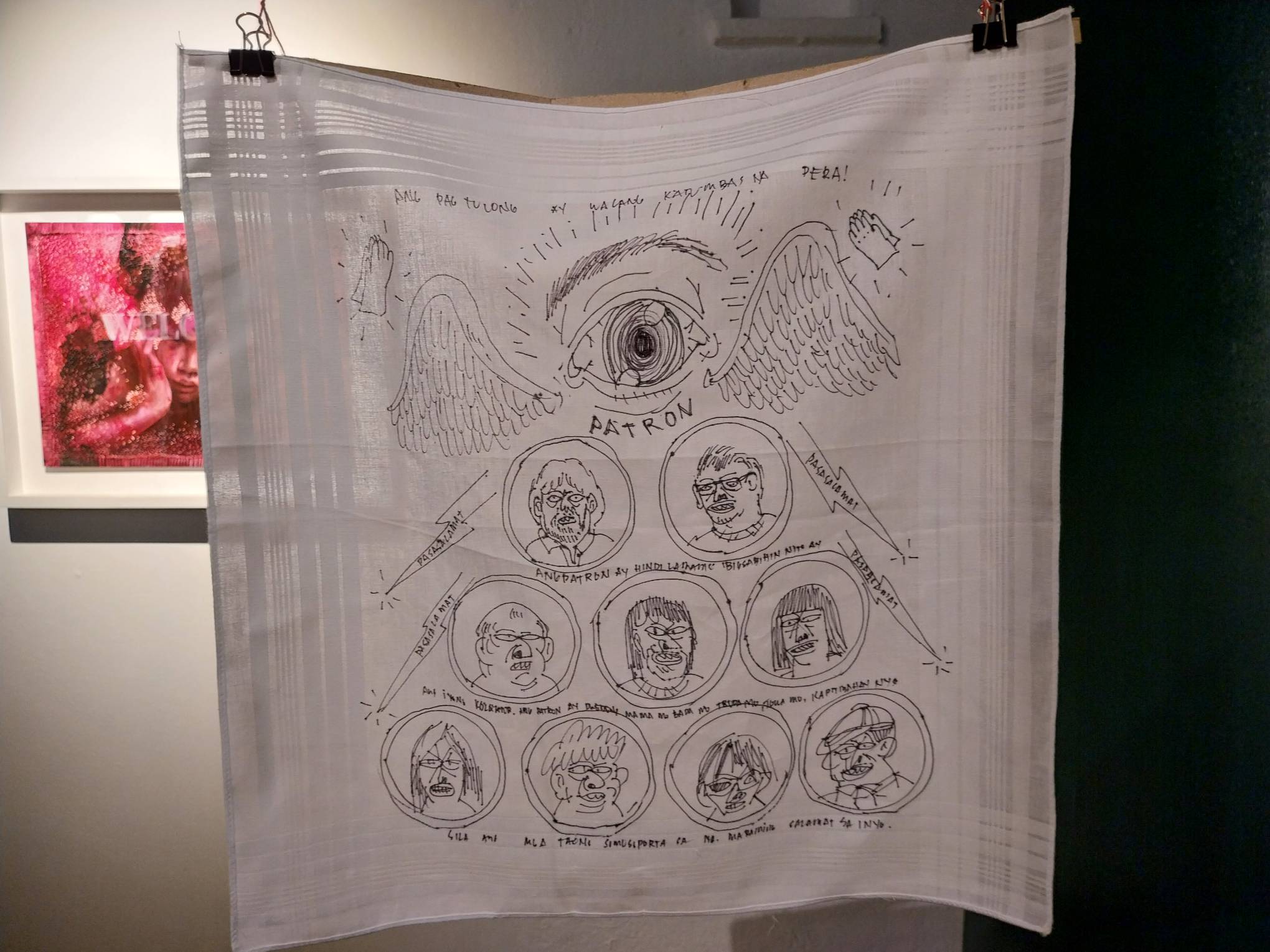

Anjo Bolarda’s “Katol…,” for example, is a literal coil of candles from Quiapo. It works as a ward for the conscience, “meant to spark the conscience of those who have others.” The All-Seeing Eye is also retouched by Mac Eparwa to become the “Anti-Palkups Eye,” as a way ensuring the artist’s continued protection in the world of today.

Standing Up For the Self

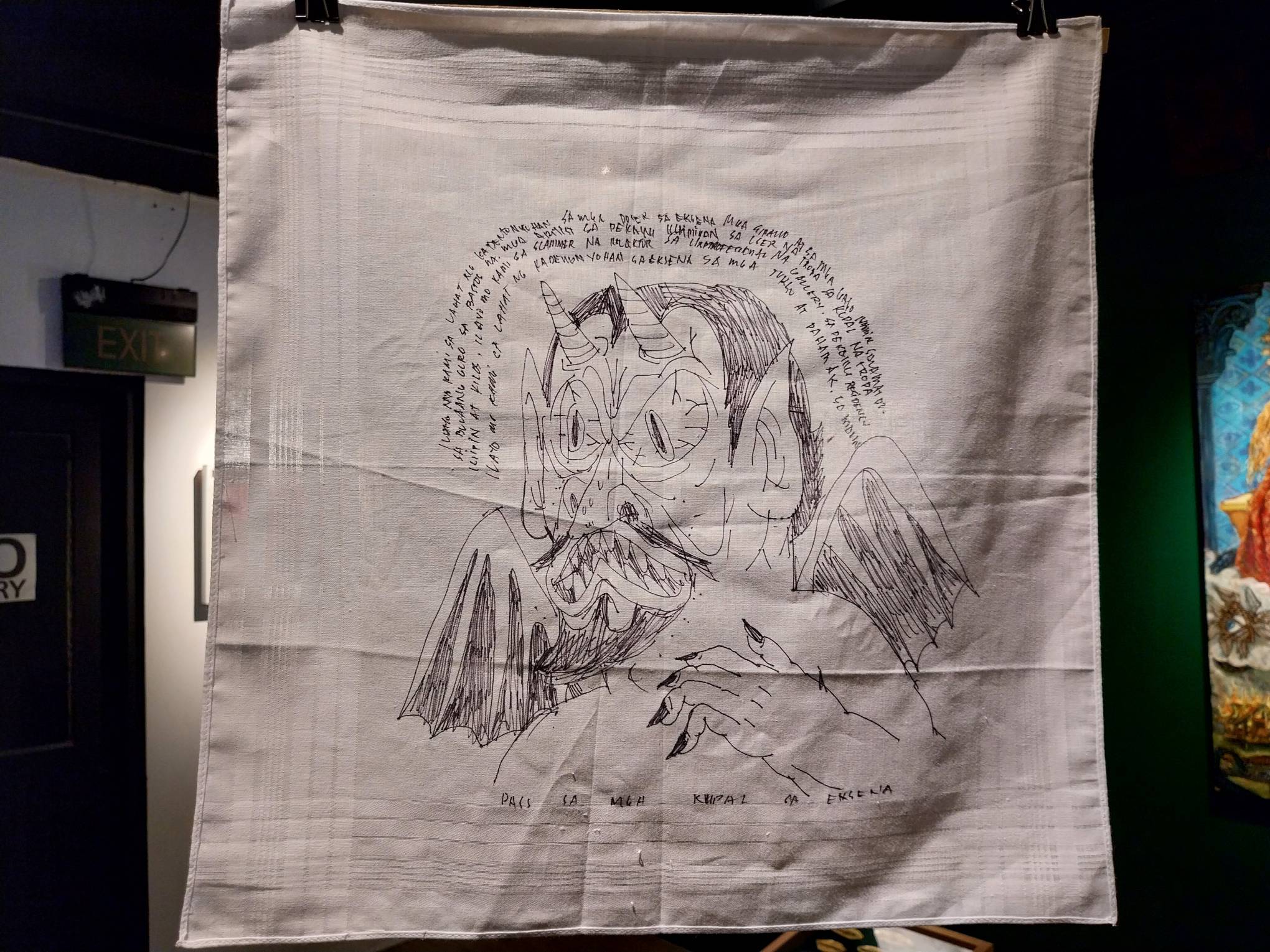

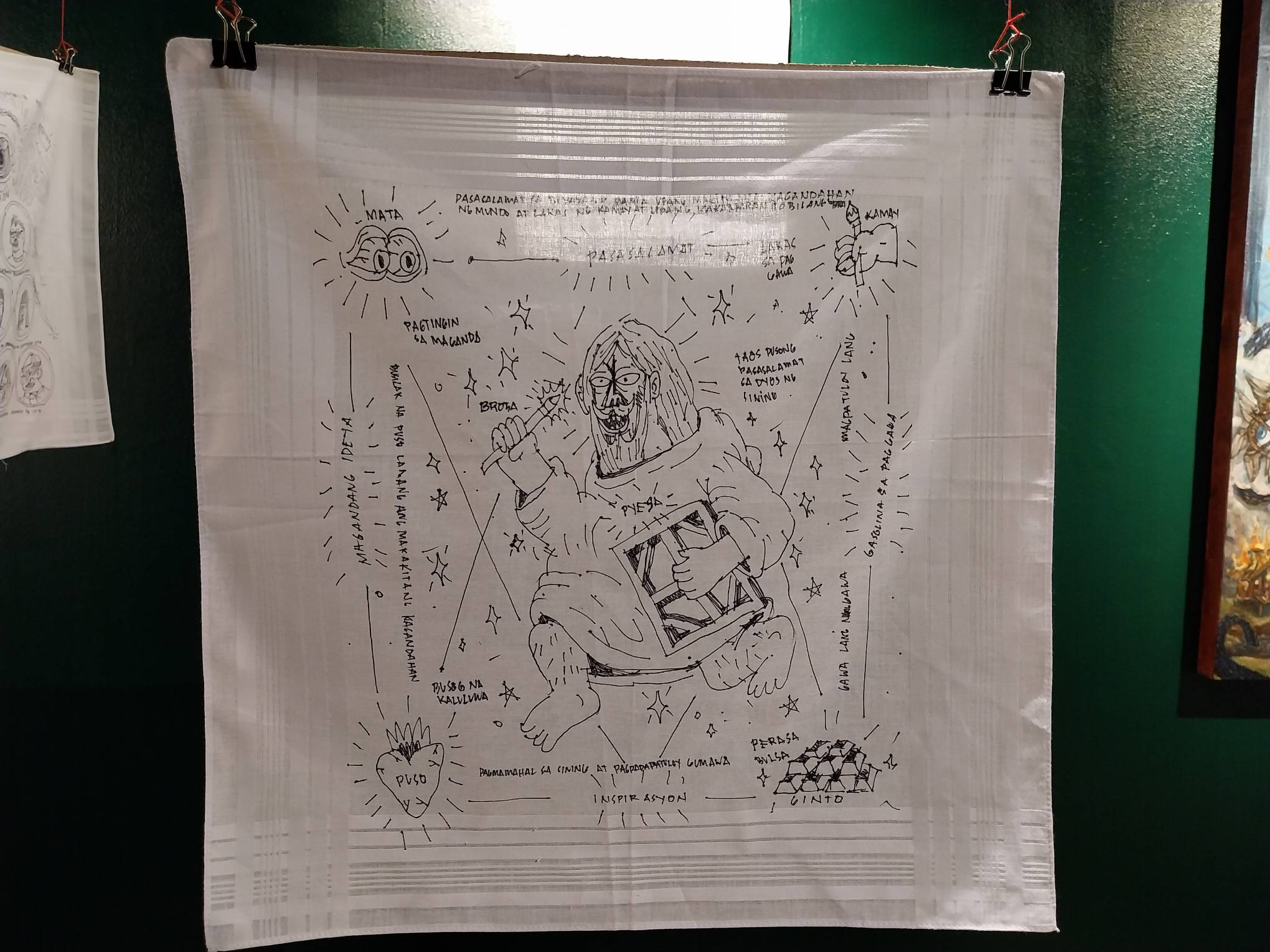

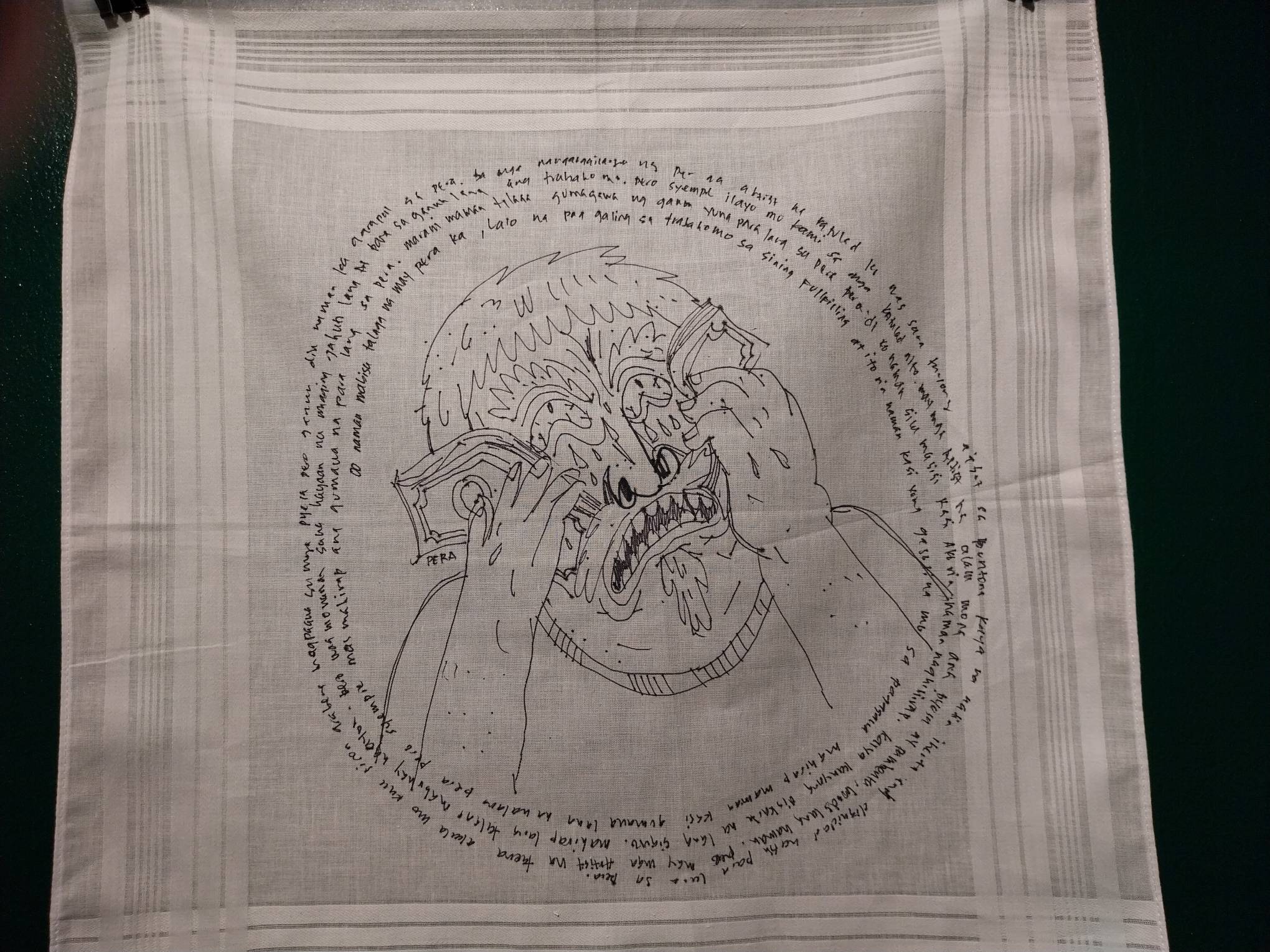

Meanwhile, other artists exhibit some creativity in subverting evil symbols to become symbols of safety. Roger Mond’s “Dasal sa Panyo 1-4” pursue a more comic bent in their commentary on the greed of the powerful and the artists’ need to kowtow to this greed to survive. Mond’s satirical pieces revel in its mockery of the elite, creating crude caricatures of them to sap them of their mystique and power.

Collectively, these artworks show the power of symbols to oppress us or to free us. One of the reasons that art is powerful is because the figures and symbols that come out of art can become a controlling presence deeply ingrained in our consciousness. The Divine Feminine or the Cross or other religious paraphernalia are powerful because they encourage people to stagnate and allow themselves to be oppressed without ever fighting back.

Thus the importance of undercutting their power. But beyond that, also renewing their meaning to ensure that they cannot be used against the marginalized ever again.

Pwera Usog allows the artist to take a definitive stand against the exploitation of creatives in the future. More than that, it gives artists an outlet to release the traumas they experienced, allowing them to move forward to potentially better futures—ones where earnest artistic expression trumps the greed of society today.

Related reading: The House Of Concrete Experiment Shows The Power Of Freedom In Architecture