Situated in Cubao, Quezon City, MIRA by RLC Residences offers a warm and thoughtful environment for couples preparing for their next chapter. Driven by the idea of home beginning long before one starts a family, this community is built around comfort, community, and the everyday rhythms of family life. Family First MIRA offers compact and […]

The Rights to the City: Public Cities, Private Enclaves

Metro Manila has faced rapid urbanization over the past decades, establishing itself as one of the fastest-growing megacities. The region comprises 16 cities and 1 municipality, totaling 17 local government units. With over 13 million people currently living in the area, its population density is approximately sixty times higher than the entire country.

In 2016, the Philippines adopted the New Urban Agenda (NUA), also known as the “right to the city,” which refers to the right of inhabitants to occupy, use, and produce just, inclusive, and sustainable cities. Guided by the pillars of sustainable development—economic, environmental, and social—the NUA for the Philippines envisions a spatially and regionally balanced development.

Metro Manila serves as an antithesis to the call for spatial justice, with its spatial organization creating a tableau where inequality is seen as much as it is felt. The neoliberal aspiration to become a global city encourages a spatial arrangement characterized by fragmented development. Researchers Peter Murphy and Trevor Hogan describe Manila as “the world’s most fragmented, privatized, and un-public of cities.”

The State and the Private Sector

Professor Gavin Shatkin states that the Philippine state holds little land, resulting in limited room for planning and master plans facing barriers to implementation due to private land owners. The state then realized that it would be seemingly impossible to create large-scale urban plans without the cooperation of the private sector. The public-private partnership model presented itself as the solution to orchestrate collaboration between the two.

Built by private developers, urban enclaves are designed to cater to the urban elite’s spatial desires for security, privacy, and exclusivity. Brazilian anthropologist Teresa Caldeira defines enclaves as privatized, enclosed, and monitored spaces for residence, consumption, leisure, and work. These gated communities range from residential developments and malls to townships and central business districts (CBDs).

Urban Development and Resilience Specialist Anna Kaaran notes the mutually beneficial outcomes of these developments for the developer and the state. The former are approved by the state to utilize spaces for maximum profit, with little to no restrictions. The latter, specifically local government units (LGUs), then views these developments as vehicles of economic growth for the city.

Enclave urbanism fosters socially homogenous communities that divide the urban elite from the masses. Not only do social classes operate as an economic group, but as a social one as well, with their own sense of identity. For the affluent, these private developments showcase a deviation from relying on state-led urban planning and resources. Meanwhile, the urban poor are left behind on the city’s margins.

This model allows for private interests to take precedence over public needs. Murphy and Hogan remarked, “The Philippines is possibly the first society in the world to have universalized the gated community.”

An Architecture of Exclusion

Urban enclaves erect borders to create distinctions within the urban population. Gated residential communities epitomize this development. They are mono-use exclusive developments enclosed by a perimeter of walls that consist of controlled entry points guarded by security personnel. Recent developments have since merged residential and production zones, creating the rise of townships as a form of exclusive development.

In September, residents from the private subdivision Forbes Park in Makati City expressed their concerns over the public outrage rooted in the multi-billion-peso flood control corruption scandal. Gone are the days of using smiling children swimming in contaminated flood waters as the face of Filipino resilience. The public has now expressed its strong condemnation of the alleged misuse of public funds to fatten the pockets of the elite.

Rappler reported that homeowners took precautionary measures to protect themselves from mobs possibly storming their village. Already segmented as a population, political turmoil reveals the fragile borders that divide the elite and the masses. For the elite, the masses are perceived as “threats” to the enclaves they’ve paid to live in.

These sentiments are also found in other developments like townships; large-scale, master-planned, mixed-use developments are often found in highly urbanized regions. Derived from the concept of a “city within a city,” these are private developments that offer amenities such as schools, parks, and shopping centers, catering to the lifestyles of the urban elite.

Central business districts (CBDs) are another form of urban enclaves. Often converging with townships, CBDs represent the region’s aspirations of attracting wealth in the global market. Within their borders, the upper strata are safeguarded from poverty, crime, and pollution, with exclusion as its defining feature.

Professor Jana M. Kleibert describes these gated communities as “visibly secured exceptions to the general public urban environment.” They all contribute to the enclavization of the city, which further drives the spatial organization of inequality in the city.

These spatial borders not only represent the existing wealth disparity but also the political and social manifestations of such differences. Despite the proximity of the slums and gated communities, there is an ever-present contention between the two. This fosters polarizing class relations in the city.

Rights to the City

There is an emerging contestation over urban space. This power dynamic begins from the establishment of enclaves, which relies on the removal of the city’s informality. This was the case for Bonifacio Global City (BGC), a mixed-use development situated on a former military camp. Its development resulted in the eviction of around 10,000 slum dwellers, according to data by the Urban Poor Associates.

For the urban elite, the city’s informality beside their private enclaves act as a hindrance to globalized development. At the minimum, they view it as an eyesore. Yet, they rely on the labor derived from these informal settlements. From taxi drivers and factory workers to schoolteachers, these residents are vital contributors to the region’s economy.

Despite their role in the urban ecosystem, the poor are subjected to an uneasy coexistence with the elite. Here, there is a disparity between the political rights of the masses and the inequality they face. They are constantly subjected to state-sponsored evictions, discrimination in public spaces, and political disempowerment.

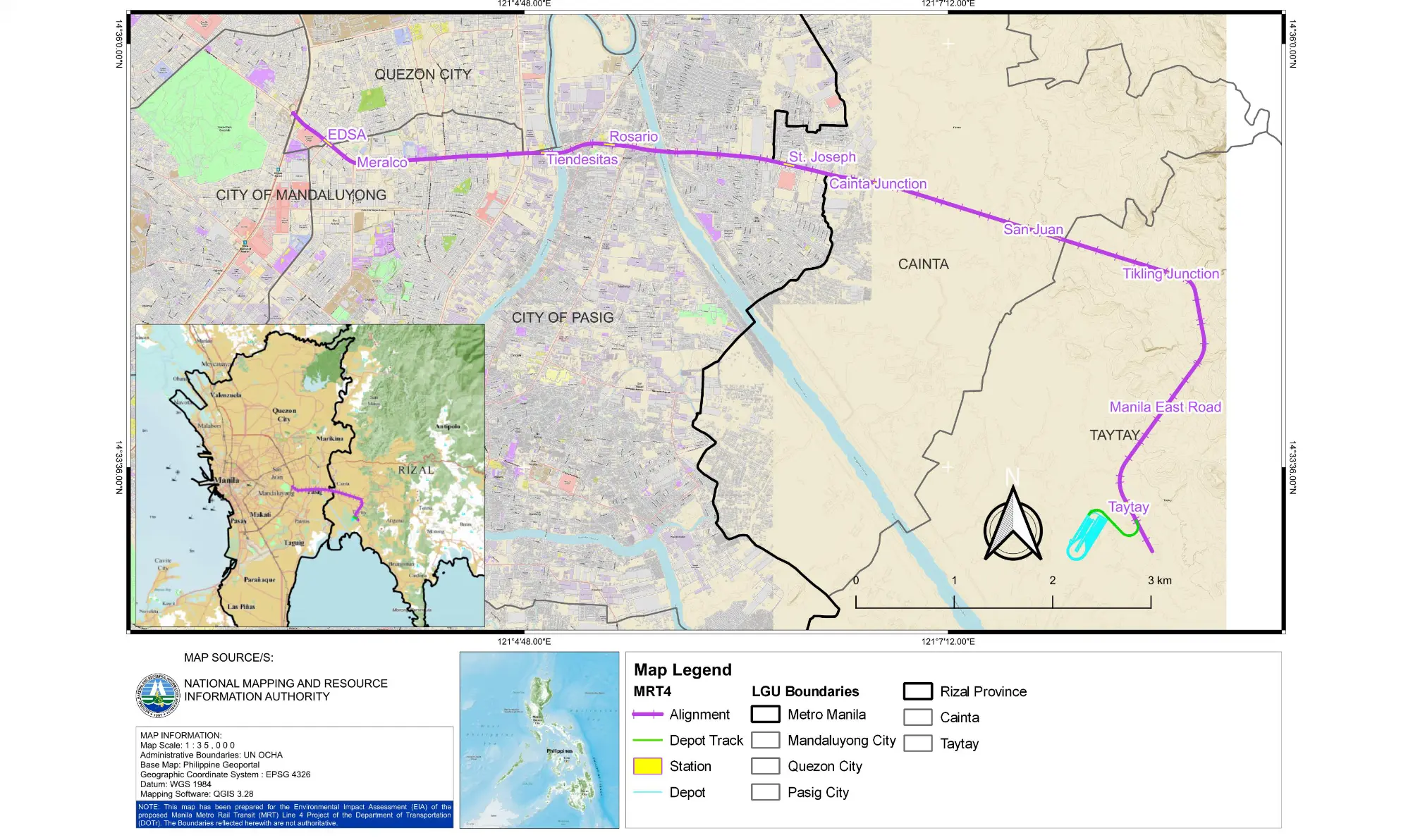

In a focus group discussion made public by the government, the residents of a gated subdivision expressed their strong opinions regarding the plans for the MRT-4 railway line. The MRT-4, with its approximately 13.4 kilometers and 10 stations, aims to address the heavy congestion along Ortigas Avenue. It is set to reduce the travel time from Taytay, Rizal, to the Ortigas Central Business District (CBD) from 1-3 hours to less than an hour.

The proposed construction, however, has faced right-of-way issues among the affected gated residential communities. Residents cited various reasons for their opposition to the proposed construction of the railway line, such as flooding, heavier traffic, increased crime rate, and the presence of “squatters and street children.”

One resident of Wack-Wack village had this to say: “You put an overhead LRT. Look at all the people you’re going to bother, you know? Who is going to secure them [from] the people taking the LRT? They can just look into the houses. ‘Oh, look at that house. We can enter that house. There are no guards.’ There are a lot of crazies out there.”

The possibility of the general public, lacking the necessary assets of money and power, gaining a glimpse into their lives serves as a threat to their private enclaves. Here, it illustrates that their walls are mere temporary shields to the poverty and pollution that remain in the city.

Residents also expressed concerns for the well-being of the students from La Salle Greenhills. One indicated how the construction of the train will be a cause of distraction for the students, stating, “They won’t be listening to their teachers. All will be watching the train.” This is the same school that has been a cause of bottleneck traffic in the area. During school pick-ups and drop-offs, students would dominate most of Ortigas Avenue’s lanes. From July 18 to August 14 alone, the school had a total of 938 violations based on MMDA’s No Contact Apprehension Policy.

Another resident proclaims, “You want to survey over the other side, where [the] Wack Wack Golf and Country Club is? Why not? You might get hit by golf balls. In our place, you follow what we want. Period. And you get along with us. If you don’t follow what we want, you’re going to have a lot of [problems] with us.”

New Urban Agenda

The NUA presented standards and principles for the “planning, construction, development, management, and improvement of urban areas.” This consists of its five main pillars of implementation: national urban policies, urban legislation and regulations, urban planning and design, local economy and municipal finance, and local implementation.

In its implementation, the NUA promises to strengthen urban governance and provide coherent urban development plans that enable social inclusion. As a resource for local governments and the private sector, the NUA understands the role of political participation in urban planning. It calls for the inclusion of vulnerable communities, such as low-income groups, in the planning and implementation of urban policies and developments.

However, the general public often faces challenges in terms of political participation. Many urban residents lack access to the resources required for civic engagement. Such resources are available to the elite, allowing them to assert themselves against both state powers and private developers.

The affluent get to boldly challenge state powers through open forums with statements such as: “Go underground. If you try to insist on putting that monstrosity above us (MRT-4), you’re going to get trouble from us… I’ll do it because I’m not going to allow you to take over.”

Meanwhile, urban poor residents who have been displaced by public development are often relocated to remote resettlement sites outside the city. There, they are cut off from their sources of livelihood and access to necessities. The general public is relegated to the margins as mere last-minute considerations.

The Philippines includes poverty alleviation, housing, infrastructure, and basic services, as well as environmental protection, settlement development, and institutional mechanisms in its major commitments. These matters are to be addressed through policies and laws (R.A. 11201) as forms of textual commitments to spatial inclusion.

With eminent domain, the state has the power to utilize public and private lands for the public good—provided it provides just compensation. However, the privatization of sustainable development creates a paradigm shift where state powers are allocated to the urban elite for further wealth accumulation. Upon observation of the spatial organization of the city, it is clear that such approaches have room for improvement in terms of spatial justice and sustainable development.

Read More: How Inclusive Design Promotes Community and Social Integration