The bookshelf is an essential piece of furniture for any home. Whether it’s for practical reasons or primarily for design, the bookshelf is ubiquitous in most homes. Its ubiquity, in fact, ensures that we don’t really think too hard about it. “It’s a bookshelf,” they would say, “just get one that can hold all the […]

Artwashing: How States Sweep the Dirt Under the Canvas

Artwashing has become a prevalent politically-contentious topic.

We can chalk that up to petrostates like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Qatar. Their recent shift towards arts and culture as a way of sustaining their economy in the post-oil future they face has garnered criticism from different groups, beyond questions of its effectiveness.

Many groups and organizations have accused them of utilizing art to cover for their human rights violations. More importantly, they’ve criticized the West for legitimizing their regimes by accepting their money and reputation. It’s not an invalid concern: the United States did give Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salmin immunity for the torture and death of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

But it’s always a more complicated topic than that.

Origins of Artwashing

The origins of artwashing comes from protests in the United States against gentrification in the country. It was originally coined in Boyle Heights in Los Angeles, an area with a large population of Hispanics, after the city designated it as an art district. Many who lived there worried that developers would use the burgeoning art scene as a way to push them out.

The term has grown over time as a way of using art to clean up the image of an institution. It’s mainly been used against corporations, specifically oil companies. We covered recently how climate activists have been targeting museums because of their use of oil money.

And as other types of whitewashing have become prevalent in criticism of countries (the most popular being sportswashing), the term has been used as a way to criticize a country with a bad human rights record that uses cultural events to cover it up.

An Attempt at Soft Power

The UAE and Saudi Arabia have been doing a soft power push for decades now. They’ve utilized their vast monetary resources in an attempt to create a “post-oil state” where their countries aren’t reliant on oil revenues. And while it’s mostly driven by infrastructure projects, there’s also a focus on promoting cultural entertainment around the world.

Saudi Vision 2030 is the Saudi government project spearheading the kingdom’s modernization. Beyond giant infrastructure projects like the futuristic urban city NEOM and the country’s Public Investment Fund, Saudi Arabia has also made strides towards gaining cultural influence around the world.

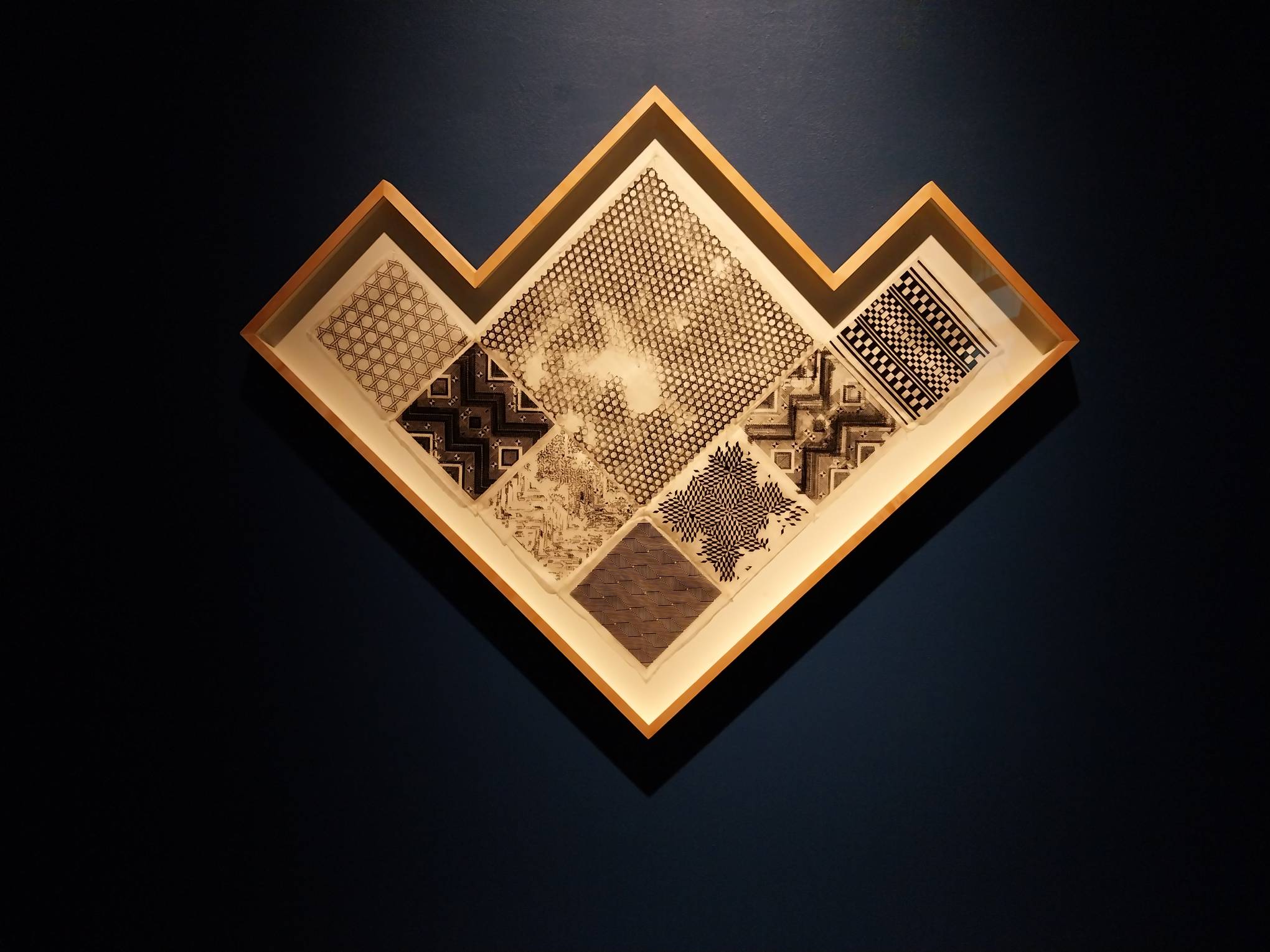

They’ve allowed movie theaters in the country, for example (their first movie was The Emoji Movie). They funnel large subsidies into art programs such as the recent Islamic Arts Biennale and the Desert X 2024 AlUla. Both highlighted the emerging art scene in the country.

Even more active in their cultural programs is Qatar, a country already accused of sportswashing after they hosted the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Over at the UAE, some of their bigger moves include partnering with UNESCO on proliferating art education across the country, as well as the opening of different giant art galleries like The Louvre Abu Dhabi and The Guggenheim Abu Dhabi.

It’s not necessarily helping their economies at the moment; arts and culture only make 1.7% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP as of 2022.

Issuing Morality to Money and Power

But this is artistry. Art can always be separated from the people who funded it, right? We have a whole literary theory about how the author is “dead” and every individual’s view on artwork is valid. Surely, just because one receives funding from Saudi Arabia or the UAE does not mean one is indebted to them?

Well, you could also argue art is never really separate from the context they were created in. Dadaism emerged post-World War I as a reaction to the horrors of that war; the Renaissance came about because of the Medicis’ funding of Italian art. The context of what’s happening in the world reflects on the work made, whether it’s intentional or not.

Even with all the progress they have made, Saudi Arabia and the UAE still has an atrocious human and labor rights record. They still have repressive policies against women and LGBTQ+ communities. More than that, both countries and many others in the Middle East still censor many works before they can be distributed in the region.

Art can still thrive in censorship, but that’s not the ideal state for art. Iran, a similarly-repressive state in the Middle East, imprisoned or banned artists like Salman Rushdie, Jafar Panahi, and Saeed Roustayi for creating art that was seen as against the State. Panahi has been able to make movies since being banned. And yet, the repression has forced him underground, creating smaller movies and documentaries than a man of his ambition would normally make.

The Centralized Power of the State

And yet, even pointing that out requires one to acknowledge that the State will always be in the conversation when it comes to the creation of art.

Art and film subsidies are a dime a dozen. It’s how European cinema sustained itself for much of the 20th century after they couldn’t compete financially with Hollywood films. Great filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman or Andrei Tarkovsky have relied on state subsidies to fund their classics.

But in many countries, it has been used to artwash the different atrocities happening within the country at the time.

The Marcoses and Artwashing

In the Philippine context, the Marcos dictatorship in the 1970s and 1980s utilized art and film as a way of legitimizing their power, creating important institutions that gave artists the audience and funding they needed to keep making art.

An example of this institution is The Experimental Cinema of the Philippines. It was opened by the government and run by Imee Marcos during the early 1980s. The perceived goal was funding films as a way to promote the growth of the film industry in the country. The organization funded classics like Oro, Plata, Mata and Himala.

The Manila Film Center, whose construction came at the cost of the injury and death of its workers, was made as a way of showcasing Manila as a cosmopolitan city, especially with its use as the debut of the first Manila International Film Festival in 1982.

It’s always a different case with authoritarian regimes. In a time when the country was dealing with the rising cost of living and massive corruption, agencies like the Experimental Cinema of the Philippines could be used by the State to artwash their reputations abroad.

The state uses the power of art to legitimize itself. It’s no coincidence that the National Artist was created a year after the start of Martial Law.

Artists have to live in a world where they have no power with the way their work is taken, or what kind of state honors their work. Many just accept it and try to do good with it. When Nick Joaquin was made National Artist, he accepted it only if journalist Pete Lacaba was released.

Artwashing: A Coda

At the end of the day, however, artists need funding. And almost nobody outside of the State or the elite are likely to give them the funding they need to survive. A balance must be struck between the commercial needs of art and the morality of accepting money from countries with abusive histories. How we strike that balance reminds us not to seek purity in our morality, but to create art that remains true to who we are and to our society.

Related reading: Our SG Arts Plan Gets Increased Funding After Successful 2023