Threats to a Treasure: The Balay nga Tisa of Carcar, Cebu

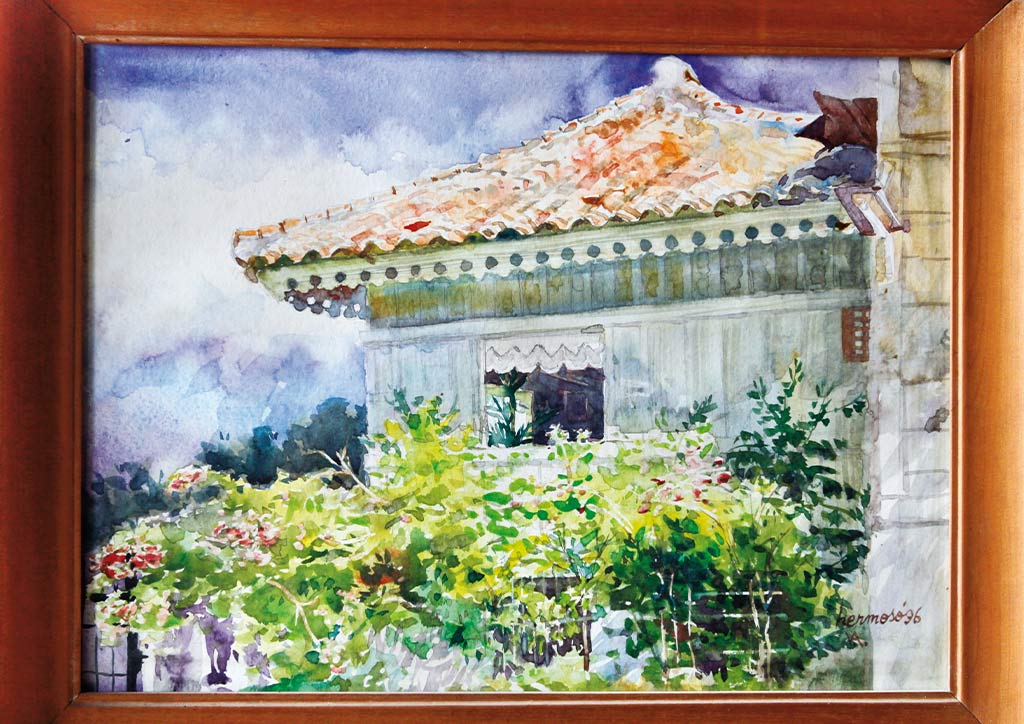

On a quiet corner of Sta. Catalina Street a few blocks away from the bustling National Highway stands the Sarmiento-Osmeña house, more popularly called Balay nga Tisa. It looks like a modest balay nga bato og kahoy (house of stone and wood) that has been whitewashed with lime. The distinctive feature is its sloping and slightly upturned roof, similar to that of a Chinese pagoda. The roof still bears original tisa or red clay tiles dating back to 1859 when the house was built, hence the house’s name.

150 years of family history

The house was built by Don Roman Sarmiento, a mestizo-Sangley from Cebu’s Parian district. He was Carcar’s earliest-recorded gobernadorcillo (circa 1856), and records also show that he was the foreman who supervised the construction of the St. Catherine of Alexandria Church in the 1870s. A marble marker on the church or near the staircase leading to the loft memorializes his and wife Ana’s donation of an organ to the church. On the account of their close ties with the clergy, Sarmiento became the recamadero or keeper of the image of St. Catherine Church’s santo entierro (image of the dead Christ), an honor that has remained in the family for five generations.

Don Roman’s house went to one of his four children, daughter Manuela, who married Jose Osmeña. They had only one child, Catalina, who, upon marrying Dr. Pío Enríquez Valencia significantly enlarged the Sarmiento-Osmeña-Valencia family tree by giving birth to fourteen children, named alphabetically from Alberto to Nilo. From this huge brood of Valencias would come cousins Manny Valencia Castro and Marc Valencia Vanzwoll, who in 1990 bought the then dilapidated ancestral home from their relatives, for the purpose of restoring it to its original grandeur.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: St. Catherine’s Church in Carcar, Cebu—a noble church on the hill

“Kami ‘yung mga baliw,” says Castro, referring to himself and Vanzwoll as the only ones in their generation crazy enough to undertake such a task. But if there is anyone in the family perfect for the job it would be Castro, interior designer, associate of the venerable Edith Oliveros, and professor at the Philippine School of Interior Design; and Vanzwoll, who demonstrated his passion and conviction for heritage conservation when he took off two years from his career in the culinary arts to supervise the initial restoration effort, which all in all, lasted five years, but is an ongoing process, says Castro.

Castro delights in the fact that the house still works, and works well. The main living and dining quarters are all functioning and its design features intact—with the newly constructed bathroom beside Balay nga Tisa being the only modern intervention. “Luma man, it’s nice to live in. But I never imagined it to become a tourist spot,” he adds.

The ravages of time

The most critical threat to Balay nga Tisa is flooding. Like many of the houses along Sta. Catalina Street, its silong is at least a foot lower than street level, owing to layer upon layer of roadwork piled on over the decades. Furthermore, the nearby river, which is choking with silt and garbage overflows during heavy rains, sending water coursing through Sta. Catalina Street and filling its lowest points with floodwaters up to waist high. When that happens, the silong of Balay nga Tisa is a muddy swimming pool.

Even when it isn’t raining in Carcar, the silong is often flooded with water seeping through the porous floor and coral stone foundation, from ancient water springs that have nowhere else to go, their natural outlets having been built on and cemented over in the last two to three decades.

On the day of BluPrint’s visit, we were greeted by this very spectacle—the caretaker of Balay nga Tisa ankle-deep in water, painstakingly bailing the water out of the front door by the bucketful, surrounded by furniture propped up on hollow blocks to keep their feet dry. On days such as these, family and guests pass through a side gate to the property, climb a staircase to the azotea and enter the house through the kitchen.

READ MORE: Leandro V. Locsin Partners reconstructs Casa de Nipa

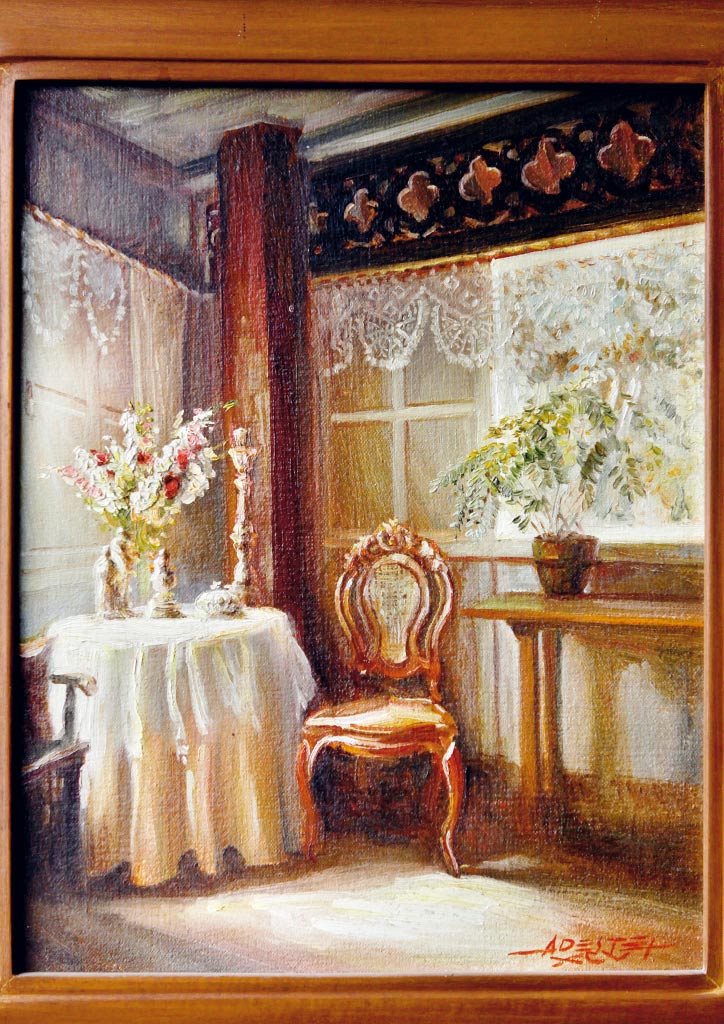

The wooden interiors of the second floor are a breath of fresh air, the exact opposite of the musty, damp silong. The rooms are bathed in sunlight from operable capiz shell windows on all sides, which are drawn wide open during special occasions—when Castro and Vanzwoll have friends over, and during the yearly festivals and Semana Santa celebrations. All over the second story are paintings of the home and its various rooms and spaces painted by friends of Castro, who he says are happy to give him the paintings in exchange for a tasty merienda in Balay nga Tisa’s comedor.

Moving forward

Like his co-members in the Carcar Heritage Conservation Society, Castro’s goal is for the city to be transformed into a self-sustaining heritage district. He believes in the adaptive reuse of heritage structures. Like his neighbors, he dreams that a diversion road will soon be built so that the busy National Highway can be closed off, and walking tours organized in and around the city center, attracting tourists and heritage buffs alike; and for the local shoe and food industries to thrive.

“It will work because I’ve seen so many places abroad that have done it,” says Castro, who opens his doors to scheduled visits by tourists and media to raise awareness of the valuable heritage Carcar possesses; and in his capacity as a concerned citizen, help spur more visitors to come to Carcar.

“For now, I’m going to keep my house as it is, the way it should be,” he says—his tribute to his ancestors and to his city. He hopes that all the balay nga bato og kahoy in Carcar, and not just the four that received NHI heritage home markers, would stand rm and endure as well.![]()

This first appeared in BluPrint Special Issue 1 2012. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Heritage travel from home: 5 virtual heritage tours to explore amidst the COVID-19 pandemic