The Manila Interior Design Summit (MIDS), held from July 18 to 20, placed the spotlight on design synergy. Organized by the Philippine Institute of Interior Designers (PIID), the three-day event became an inspiring gathering of interior design professionals, enthusiasts, and industry leaders from around the globe as it followed the theme, “A Festival of Collaboration.” […]

7 Heritage Batangas Churches to Visit this Holy Week

Taal’s fury and human vanity reverberate in Batangas’ churches in every city and municipality highly influenced by the Spanish, especially of Catholicism. In the tradition of Visita Iglesia, we revisit seven of these ancient Batangas churches that stood the test of natural disasters and peoples’ interventions through the centuries.

During Holy Week in the Philippines, many people observe the tradition of Visita Iglesia. This involves visiting seven or fourteen churches and offering prayers at each for a special intention. While saying an invocation is the primary and most important reason to visit the church, another motivation is to remind ourselves of the history and heritage of these Batangas churches this Holy Week.

1. The Immaculate Conception Parish Church, Balayan

In its 422-year history, one of the oldest churches in Batangas, standing in the province’s oldest town, has witnessed its fair share of disasters and destruction—both natural and man-made. The Immaculate Conception Parish Church in Balayan served a dual purpose; the first as a sacred sanctuary, but also as a fortress built against Muslim invasion, which occurred almost yearly. It was reinforced after the 1754 Taal Volcano eruption and against the greedy capitalists’ plans of commercialization.

The structures that the now vigilant Balayan community fiercely wanted to protect, which currently house the Immaculate Conception convent and school, used to be Balayan’s Casa Real, or the municipal tribunal, built 1744. The church itself bears a historical marker, installed December 8, 1986, by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP). Its status as National Cultural Treasure protects it by law from physical alterations that may violate the authenticity of the church’s historic identity. Such protection extends to the church grounds, and before any new construction may take place, requires NHCP approval.

READ MORE: The Mod-art and Mid-century Leanings of Basilan cathedral

2. The St. Raphael the Archangel Parish Church, Calaca

St. Raphael is deemed the patron of the sick, especially of the blind or those afflicted with eye illnesses, and of healers, doctors, lovers and travelers.

He is also the patron saint of Calaca, a town in Batangas established May 10, 1835. It was originally part of Balayan. Six years after Calaca was established, Diego Inumerable, the gobernadorcillo or governor of Calaca, deemed the town ready for its own parish church. He had the church of St. Raphael the Archangel built, with the help of Calaca’s elite parishioners.

The men and women of Calaca volunteered to gather the materials needed for the church’s construction: sand, stone, wood. They brought these to Balayan through the Pansipit River to the shore of Calaca, which borders the southern part of the town. From the shore, the people hauled the materials to the church. The roof is made of wood and hard stone bricks, while the walls are made of adobe, limestone and sand. Completed in 1861, it marks the official status of Calaca as a parokya (parish).

3. The Basilica de San Martin de Tours, Taal

This quaint town in Batangas bears the name of the smallest active volcano in the world, and is home to the largest Catholic church in Asia. For these reasons and others besides, the town has been described as “a town of superlatives.”

READ MORE: A Fitting Retrofit: The Restoration of Manila Cathedral

The original structure of Basilica de San Martin de Tours used to be in what is now the town of San Nicolas. Built in 1575, the cataclysmic eruption of Taal Volcano in 1754 completely destroyed it, and the entire town relocated to its current site. The present church was inaugurated in 1865, but was only considered finished in 1878 when Fr. Agapito Aparicio added the Doric style main altar.

On December 8, 1954, Presidential Decree No. 375 declared the Batangas church a Minor Basilica, and 20 years later a National Shrine, or a National Historical Landmark. For 148 years since its inauguration, the church weathered major earthquakes and underwent several restoration, rebuilding, and controversial beautification efforts.

A Renewed Sanctuary: Restoration Efforts at the Basilica

The Basilica used to have two belfries, but both fell due to a 1942 earthquake. Reconstruction began on the left belfry in the early 1990s, but the result caused much uproar among the parishioners and heritage lovers, as the shape was too narrow and the dome looked like a milk bottle’s nipple. Two years later, the new belfry’s thickened walls and wider roof make it look more like the original. Architects likely did not rebuild the second belfry because the Basilica’s coral stone structure wouldn’t have been strong enough to support the weight of a new dome made with heavy modern cement.

Upon his appointment as Taal’s parish priest in 2011, Rev. Msgr. Alfredo Madlangbayan improved the interiors of the Basilica with the help of the Church Historical Authentic Restoration Movement (CHARM), and under supervision of Arch. Reynaldo Inovero of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP). Later, the construction of Casa San Martin II Jubilee Hall was also conceived.

Madlangbayan’s zeal for instituting improvements, however, became the target of an equally zealous Batangueño, celebrated glass sculptor Ramon Orlina, whose love for his hometown has spurred him to protect its status as a heritage zone.

4. The Basilica Menor de Inmaculada Concepción, Batangas City

The Basilica Menor de Inmaculada Concepción is 156 years old. But in 1581, over 430 years ago, Augustinian priest, Padre Diego Mojica, erected the first church that stood on its site. Dedicated to Inmaculada Concepción de Nuestra Señora, the first structure was made of wood. Over the course of four decades, from 1682 to 1721, the parish built a large and fortified church complex in the same location. In 1693, the complex gained a high watchtower and artileriya added to the convento to espy and repel sea bandits.

READ MORE: Sculpted illusions at the Basilica Minor of Immaculate Conception in Batangas

A History of Resilience: From Early Beginnings to the Present Basilica

Several sources, including the marker outside the basilica, indicate that the second church was demolished in the mid-1800s to make way for the construction of a third church. The reason for the demolition remains unclear, but it likely stemmed from the severe damage caused by two destructive earthquakes that struck in 1852, on September 16 and December 24.

The third church, the present one, is a picture of solidity and stability, its walls a meter and a half thick, supported by three massive buttresses on each side. Consecrated on February 2, 1857, a decree by Pope Pius XII in February 13, 1948, elevated it to the status of “Basilica Minor,” making it the first church in the Philippines and East Asia to receive this honor.

5. The Church of St. James the Greater, Ibaan

A frequent casualty of natural disasters is the Church of St. James the Greater in Ibaan, Batangas. The first chapel and a convent that the town had, according to records, were engulfed by a storm that brought “fire and sulfur” in the early 1800s.

It wasn’t until 1832 that the Order of St. Augustine, which established its foothold in the province as early as the 1570s, proposed plans for a larger church for the town of Ibaan. An architect named Luciano Oliver drew a cruciform layout for the church, with a transept near the retablo housing two more altars. Made of adobe stone, the church has a triangular pediment, ionic columns, and two bell towers flanking both sides of the façade. The adobe comes from a quarry along the Ibaan River.

Natural disasters followed in the coming years, in the form of two earthquakes, the first one in 1890 and the second at the height of World War II. The earthquakes destroyed the church, causing for rebuild and replacement of the east tower.

Endurance Through Time: Despite Repairs, the Church Stands

Today, the façade of the church has been covered with cement, purportedly to make up for the deterioration of the stones. While the new cement finish succeeds in replicating Luciano Oliver’s design of the façade, using modern cement instead of traditional lime mortar on the ancient stones was an ill-advised decision. Lime mortar is much more porous than cement mortar, allowing dampness within the stones to evaporate, unlike modern cement, which traps moisture inside and hastens the deterioration of the antique structure.

READ MORE: Shelter dialogue recap: Building architecture, disaster-resilience, and AI

Still, the fact that the church remains standing despite suffering at the hands of two earthquakes is a feat, interventions and all. It seems like St. James the Greater, seen by the people of Ibaan as the church’s “Defender of Faith and Freedom,” has done his job in defending it from destruction, whether from natural disasters or human hands.

6. The Archdiocesan Shrine of St. Joseph, San Jose

The Batangas town of San Jose, named after Joseph the father of Jesus and husband of Mary, is home to the Archdiocesan Shrine of St. Joseph. The Oblates of St. Joseph Mission and its Minor Seminary, the first Italian congregation that sent missionaries to the Philippines, established the Batangas church as its base.

Augustinian friars put up the first church in the town in 1788, built with bamboo and a cogon roof. A fortified structure made of adobe, the church still stands today, constructed in the early 1800s under the watch of Fr. Manuel Blanco. Records are inconclusive about damages the church suffered in its more than 200 years of existence; the façade stripped of its palitada and coated with cement. According to a parish official, builders applied cement to protect the church’s façade from rain, as the stones already had cracks due to old age. However, no records exist as to when they made these repairs, or whether they used the right kind of cement.

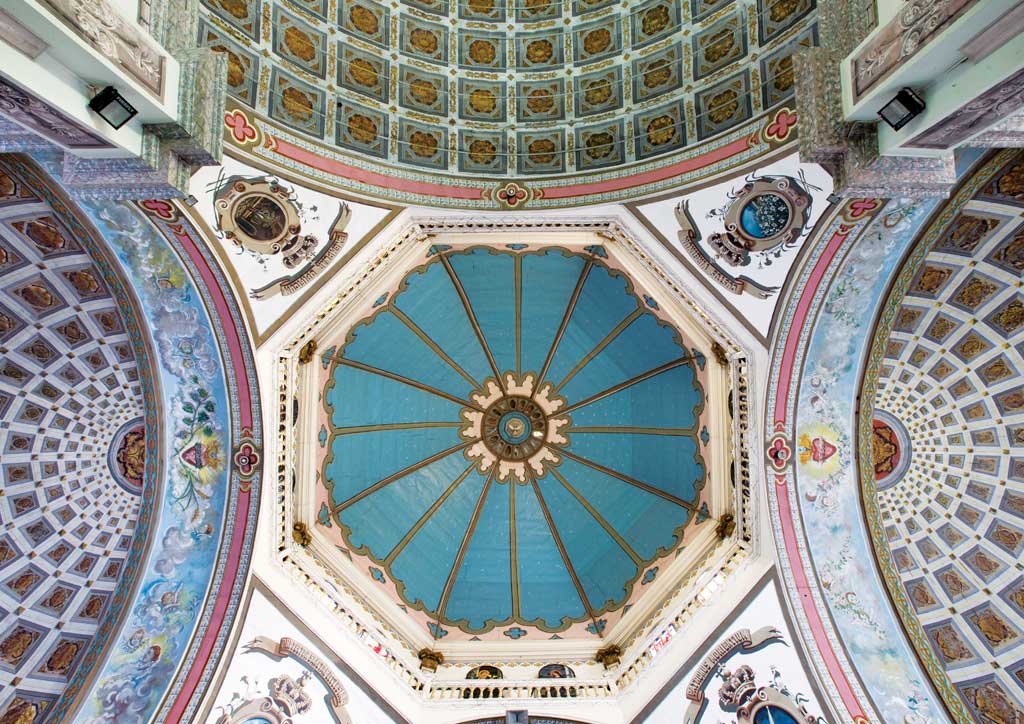

Baroque Beauty and Enduring Faith

The church is rife with Baroque influences, as evidenced in the curved cornices of its façade and the intricate, floral details of its interior. It follows the cruciform layout, a common feature of churches built during the early Spanish period.

In contrast with the bland cement façade, the church interiors are striking for the well-preserved state of the trompe l’oeil paintings and details for the ceilings, arches and columns. Painted scenes from the Bible grace the sidewalls, which feature painted shadows and frames to create a three-dimensional sense of depth and relief.

The church’s Baroque ornamentation and well-preserved state have made it a popular pilgrimage site, particularly for women who come to St. Joseph and pray for their spouses. With the Oblates of St. Joseph still using it as their base for spreading the Good News, the Archdiocesan Shrine of St. Joseph will continue to stand as a father figure for the town of San Jose for more years to come.

READ MORE: The Xavier Nuvali oratory echoes rock imagery in Christian tradition

7. St. John the Evangelist Church, Tanauan

Established on May 5, 1584, records place the completion of Tanauan’s earliest church structure—a wooden one—before the year 1690. Forty years later, Tanauan was prosperous enough to complete an edifice made of stone in 1732. However, the cataclysmic eruption of Taal Volcano in 1754 demolished it completely, along all of the town’s houses, as well as those of all the other population centers along the lake—Taal, Balayan, Bauan, Lipa and Sala.

A History of Flight and Rebuilding

According to some accounts, the Tanauan townsfolk fled at the first to a nearby town called Bañadero. They later relocated some eight to ten kilometers inland, towards the east, to Tanauan’s present location.

In the center of their new town, the Tanaueños built for St. John the Evangelist a stone church with a tile roof. Subsequently, the church underwent expansion twice, in 1861 and 1881.

The American carpet bombing of Batangas, then crawling with Japanese during World War II in 1944, flattened most of St. John’s. After the war, the church underwent reconstruction. This last major restoration effort marked the disparity between the church’s traditional, somewhat florid facade, and its sharp, modern interiors.

The National Historical Commission declared St. John’s a heritage site in 1991.