This article first appeared in BluPrint Vol 3 2013. Edits were made for Bluprint online.

A hundred walls for worship in Cebu by CAZA

From its rich heritage of Spanish-era churches to Modernist shells of the 1960s, Cebuanos have been building churches and chapels since Magellan’s cross was first planted on the island. The island itself has undergone many changes in the last 400 years. Metropolitan Cebu has been augmented by reclamation that started southwest of the city in the 1960s. The economic hubris of the 1990s emboldened officials to replicate the process northward—hence, the South Road Properties (SRP) was born.

The SRP attracted big development players, who promptly mapped out new enclaves for their “masterplanned mixed-use lifestyle centers.” SM Development Corporation snagged a key parcel close to the historic core of the city (connected via a tunnel that enabled the city to conserve its historic Fort San Pedro and Independence Plaza). Continuing a template tested at their Mall of Asia complex, SM started the transformation of that seaside site with a religious structure.

They commissioned a Filipino-Colombian architect Carlos Arnaiz based on his Chapel for the Chosen Children in Tagaytay. The small but elegantly designed structure, completed in 2010, had created a buzz. SM hired him first for a small chapel at Hamilo Coast, and were impressed with his design so they offered him the Cebu project.

READ MORE: CAZA’s new CamSur Capitol inspired by Pili and Mt. Isarog

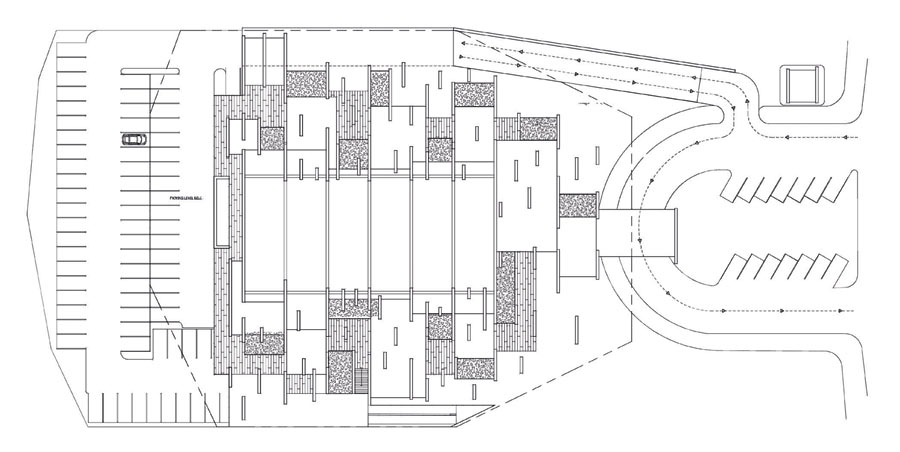

Arnaiz and his New-York based firm, CAZA, quickly developed schemes for a larger structure to seat a congregation of 800. The half-hectare site chosen by the complex’s master planner was east of the water’s edge. It needed to be elevated above the flood line of the adjoining channel. This gave the architect the opportunity for additional back-of-house spaces and meeting rooms that he placed below the main floor.

The main floor plate is essentially rectangular, although there is a transept with space at the cross for half a dozen pews on either side. All this is not evident from the approach to the chapel as Arnaiz’s parti deconstructs the traditional silhouette of churches. His chapel is an asymmetrical composition of walls, a hundred in number, with no horizontal plane of roof, save for a front canopy, to confirm the spaces inside.

The chapel looks like a Modernist Stonehenge—the name CAZA staff used to call the project while in development. The white elongated slabs of concrete, all of different heights, cast shadows that animate the structure as one moves around and closer to it.

Only at arrival do you see the portal to spaces inside—massive top-hung doors made from salvaged wood. An earlier scheme of the architect showed a tower, but this was replaced by a simple cross, attached to the façade. The structure has also been called “The Church of 100 Walls.” The intent, says the designer, was to reflect the diversity of “society today, along with the different ways modern Catholics take to access God and involve themselves with other faithful.”

Despite the nontraditional approach to the envelope of the chapel, Arnaiz is surprisingly traditional in major elements he included. Before entering the main space, there is a narthex, or vestibule, albeit semi-open. The multitude of walls, since they are all parallel, provide natural light; much like the tall arches of Gothic cathedrals. The roof of the structure is flat but tiered, also providing natural light through clerestories—again, a traditional device.

READ MORE: God, Man, Nature: Amara Chapel by Buensalido+Architects

There is also a choir loft above the left transept, which is not unusual, although this is found in more contemporary churches. The main space of 4,000 square meters is not very tall but verticality—which leads the eye upward like Gothic cathedrals—is implied with the many walls and the glazing between them. There is a traditional nave, which divides the congregation in two. The pews are of solid wood in a restrained design that blends with the space.

The finishes in the interior were meant to be in Mactan stone, but after finding out that further quarrying would compromise the environment of the province, the designer opted for a faux Mactan stone finish. Beyond these, everything else is non-traditional. There is a chancel and sanctuary area for the altar but there is no communion railing. There is no retablo but three statues adorn an abstract treatment of glass fins on the altar wall. The statues—including St. Peter Calungsod’s—are disappointingly traditional, but apparently this is a temporary situation according to Arnaiz, who would prefer more avant-garde pieces.

There is an adoration chapel, but it is not inside the main space. What is inside is a children’s room, a sound-proof room for rambunctious kids—a great idea that more Catholic churches should adopt. Outside the main space is an ambulatory, a traditional element, but because of the asymmetry of walls, much less formal spaces are produced. Here, Arnaiz has distributed the Stations of the Cross, interspersed with cut-outs that look down into pocket gardens at the basement level.

The Church of 100 Walls does provide both traditional and nontraditional spaces. CAZA is successful in melding the two and producing an architecture that enhances the religious experience. The creative expression of the hundred walls does not detract from the overall feel of the spaces.

The chapel is that type of place people would visit repeatedly; every visit can be different depending where you sit, walk, stand or kneel for worship. According to Arnaiz, the chapel embodies modern faith and spirituality without limiting constraints, saying, “Here, it’s not like you are being dictated to, that there’s only one way to God. He is experienced in different ways, and the Church is the symbol of that reality.”

I do miss the element of the plaza in front of the chapel (or church). This open space can serve to blend all the structures planned for the site. I have a feeling that Arnaiz’s hundred walls would be better experienced with active public space fringed with shade trees and arbors. Harvard-trained Arnaiz did work for a spell with Field Operations, the landscape architects responsible for the popular High Line in New York. He understands the value of open space and landscape setting to bring out the best in architecture and people.

Nevertheless, a chapel (especially since it is dedicated to our newest saint, and a Cebuano at that) is a good start. For Arnaiz, he now has three religious structures under his belt, which is unusually lucky for an architect. Maybe he will design 97 more. ![]()