Preserving the Memory of Dr. Pio Valenzuela and His Bahay na Bato

Heritage structures are markers for a people’s identity. They serve as windows that allow us to peer into the conditions of our society’s past by the implications of their physicality. Furthermore, these buildings hold memories of the events that occurred and through the associations people have with the place. The historic home of Philippine revolutionary Dr. Pio Valenzuela is a prime example of this. It embodies the memory of his dedication and service, which were instrumental in securing the freedoms we cherish today.

The Clamor For Heritage Spaces in Valenzuela City

People widely regard the City of Valenzuela as an industrial zone. The extensive presence of manufacturing plants and distribution warehouses makes the area less than ideal for residential living. As such, the local government began to focus on initiatives to make the city more livable, focusing on the well-being of its constituents. It wanted to establish more arts and cultural facilities and public spaces to make the area feel more welcoming and alive amidst the urban development.

Related Read: https://bluprint-onemega.com/what-makes-a-great-philippine-city-part

The inception and conceptualization to erect a museum started way back in 2009 from the previous administration. In 2019, The city started construction to commemorate the 150th birth anniversary of the city’s namesake, Dr. Pio Valenzuela. They commissioned Arc Lico International Services, Corp. (ARC LICO), a multi-disciplinary team of heritage conservation experts led by Dr. Gerard Lico. Lico is a seasoned veteran in heritage conservation and art history, who has a track record of notable heritage projects such as Rizal Memorial Coliseum and the Metropolitan Theater, to restore the house for public use. ARC LICO took on the daunting task of reviving a structure in a story of remembrance and community. It involves the manner that architecture can display a story and history through ethereal and substantial means.

The History of Dr. Pio Valenzuela and His Home

Dr. Pio Valenzuela (1869-1956) was a prominent leader of the Kataastaasan Kagalanggalang na Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (KKK). He served as a physician and oversaw the revolutionary group’s publication, Ang Kalayaan. During the American period, he served as municipal president of his hometown Polo, Bulacan (now Valenzuela City) from 1902-1919 and as the 10th governor of Bulacan. Afterwards, he continued to serve his community as a philanthropic medical practitioner. Shortly after his passing, the government renamed his hometown of Polo to Valenzuela in his honor in 1960, in recognition of his significant contributions.

The Pre-War Home

Because of his role in the Philippine revolution, he faced a series of arrests from both the Spanish and the Americans. Returning after three years of imprisonment from 1896-1899, Dr. Valenzuela decided to settle down. He got married and built a stately bahay na bato in Polo for his new family.It had two floors, an azotea, a clinic, and several aljibe (water wells). For many years, he received guests at his home and attended to the sick in his clinic on the ground floor. Sadly, the Japanese burned down the original pre-war home during World War II.

The Post War Home

After the war, a proto-modern home was built on the same site. Unlike the initial grandeur of the bahay na bato, a more modest structure was built as the nation was still recovering from war. Valenzuela lived in this house until the end of his life. After his passing, his descendants continued to live in the home for several decades.

The main issue of the site was its low elevation, which made the post-war home prone to flooding. Despite other homes and the street level being raised, the structure was left in waist-high waters that made it a risk for health and safety. Rather than leaving the home in disarray, the family decided to partner with the city government to have the home rebuilt as a museum. It was a marked site by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), which makes it so that any modifications would require approval.

In 2019, the NHCP gave permission to the family to conserve the house to a more dignified condition. Instead of restoring the post-war house, the family requested rebuilding the pre-war bahay na bato instead. However, no one actually knew what it originally looked like as there were no available plans or pictures of the residence.

Establishing the Authenticity of the Structure

It is a daunting task to convert a ruined house into a museum that can reflect the life of Dr. Valenzuela. In retrospect, the history of the house parallels the cycles of his life as a revolutionary, civil servant, and doctor. The decision was made to restore the pre-war house, the property held by Dr. Pio at the height of his involvement with the nation’s history, and helped preserve the roots of the City as the original town of Polo.

A Philosophy for Restoration

“The ultimate goal of preservation or conservation is to commemorate certain memories.”

ARC LICO shared a hybrid approach towards conservation that forms the conceptual framework of this project. It captures the tangible and intangible aspects of buildings to arrive at a holistic approach to preserving architecture.

A Hybrid Approach to Conservation

Maintaining the home’s connection to Pio Valenzuela was essential in establishing the architecture’s authenticity and preserving his memory. The difficulty lies in the lack of a mental image of the actual home. ARC LICO primarily addressed this by using the very same materials Valenzuela himself touched and walked upon.

Semiotics, our understanding of symbolisms, communicates meaning to us in line with Valenzuela’s revolutionary and civil role. Memory also enriches past experiences and events that occurred within or in relation to the space. Cultural phenomena and historical fact gives further basis for the direction the design can take. All of this can be distilled into a legibility of spatial characteristics that’s understood by it users.

Using a more concrete architecture-related example, the Japanese have a practice of rebuilding shrines every 20 years. Despite the removal of the physical materials, this continual renewal retains the structure’s memory and cultural significance. It preserves the intangible spirit, belief, and actions through this cycle of death and rebirth. The history of the home can also be interpreted as to follow this pattern.

This relates to the Ship of Theseus; a thought experiment that challenges the notion of originality. Through the passage of time, each piece of the ship was modified or replaced to maintain its condition. But it begs the question: can it still be considered Theseus’ original ship?

Bringing the Bahay Na Bato to the 21st Century

“The paradox of its long life and its survival is change. You have to evolve with the changing times to be relevant to the people.”

Lico shared that heritage buildings are not frozen in time, their continued use will ensure their survival. As such, there is more to heritage conservation than solely preserving authenticity. The aim of the project was not to rebuild a bahay na bato in its pure traditional form. Rather, they wanted to recreate the experience and the emotion from navigating its spaces. It also needed to translate Dr. Pio Valenzuela’s legacy in a fashion relevant to the 21st century.

Building a public museum required changes to the architectural programming of the house. Contemporary methods of construction and technology are employed that aligns the structure with present needs. Furthermore, practical demands such as building safety, code compliance(National Building Code), accessibility, and upgraded utilities all had to be met. Lastly, the structure had to be future-proofed and should address the changing site specific conditions like raising flood water in the City.

The Process of Reviving Dr. Pio Valezuela’s Home

We celebrate Valenzuela as a public figure for his impactful contributions that positively influenced countless lives through more than fifty years of public service. Similarly, his home, now a public venue, aims to foster that same sense of inclusion and community for all individuals, regardless of their background.

ARC LICO believes that heritage should be enjoyed by all. The genesis of the project involved numerous stakeholders ranging from Valenzuela’s descendants, the community, and the city government. This allows them to emotionally engage with and respond to the space as they navigate it. Facilitating a dynamic relationship between the community, the structure, and the local government unit can help ensure its use and proper maintenance.

Planning

“In any conservation project, you have to consult the stakeholders. Every voice should be considered.”

Again, it was difficult to build the pre-war Bahay na Bato since most plans from that era were destroyed as a consequence of World War II. ARC LICO treats memory as a viable and valid source to inform the project’s design. As fortune would have it, one of Valenzuela’s grandsons, Arturo Valenzuela is an architect who helped map out the spaces and prepare the plan. Arturo sketched the pre-war bahay na bato plan and facade from his memory and recollection. The ARC LICO team consulted numerous sectors to align the purpose of the project and its responsiveness to all.

There was an emphasis on being historically accurate in every possible aspect. They analyzed structures built during the same era within the region to further inform the design’s architectural characteristics and motifs. The modest design, as opposed to one of extravagance, is in keeping with Valenzuela’s identity as he was remembered by his community and loved ones.

Landscaping

The team installed sheet piles and drained the site to elevate it 1.5 meters above road level for both symbolic and practical purposes. Raising the structure reinstated it as a focal point and community landmark among the neighboring houses while also mitigating future flooding. The frequent flooding and nature of the soil in the area caused the ground under the home to soften significantly, weakening its ability to support heavy loads. This made it unsuitable for concrete construction. To address this, they reinforced the ground using micropiling, which involves inserting small-diameter rods to strengthen it.

The designers enhanced the site’s rehabilitation by adding more greenery, which helped distinguish the property from its immediate surroundings. They added a gazebo from the American period to introduce a use case for the garden. It further creates an atmosphere that transports visitors back in time.

Along the site entrance, monumental steps establish a distinct entry into the grounds. Accessibility functions such as ramps for wheelchairs, pedestrian design, and vehicular amenities were also added. To enhance its utility for public events, they set up a stage along the street, with the museum serving as a backdrop for community activities. The inclusion of a fixed stage doubling as a practical lay-by area along its adjacent street provides a practical and ingenious design solution.

Construction

Heritage conservation is a highly technical form of construction, which presented a challenge for the project’s contractor who was more familiar with the conventional construction practice. Fortunately, ARC LICO had just completed a 2-year conservation of a 1920’s house conservation project in San Juan. This gave the team the insight and experience necessary to navigate this particular process of construction. The team guided the contractors in properly conserving certain portions of the structure such as wood restoration and molding fabrication. A pool of highly skilled artisans were also employed to recreate portions of the building like the capiz windows using the traditional style of fabrication.

In compliance with modern construction standards, steel beams and concrete slabs form the structural framework of the house. This is essential for the project’s longevity so that future generations can benefit from it. However, the building’s “skin” is still made from the original material, which thoughtfully retains the structure’s authenticity.

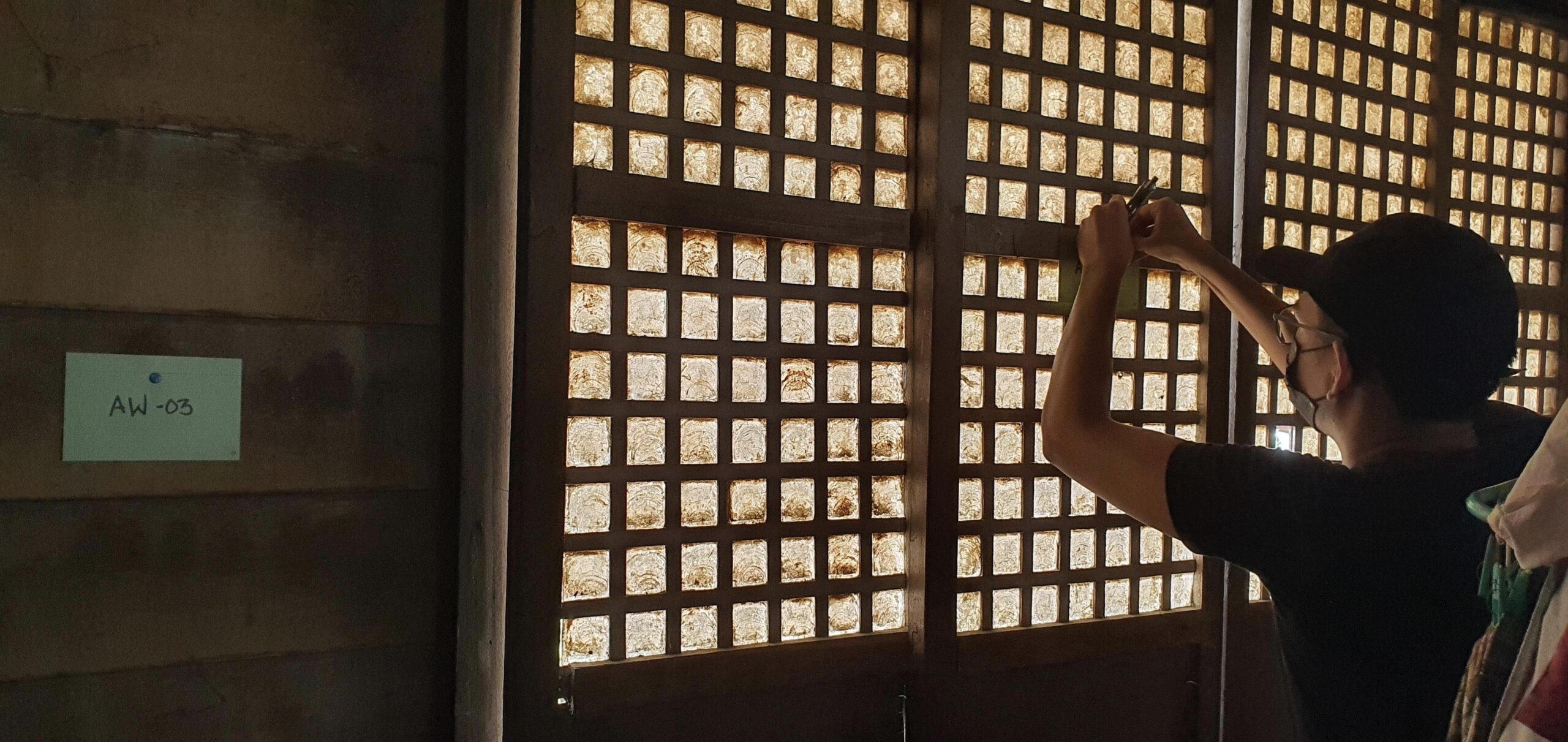

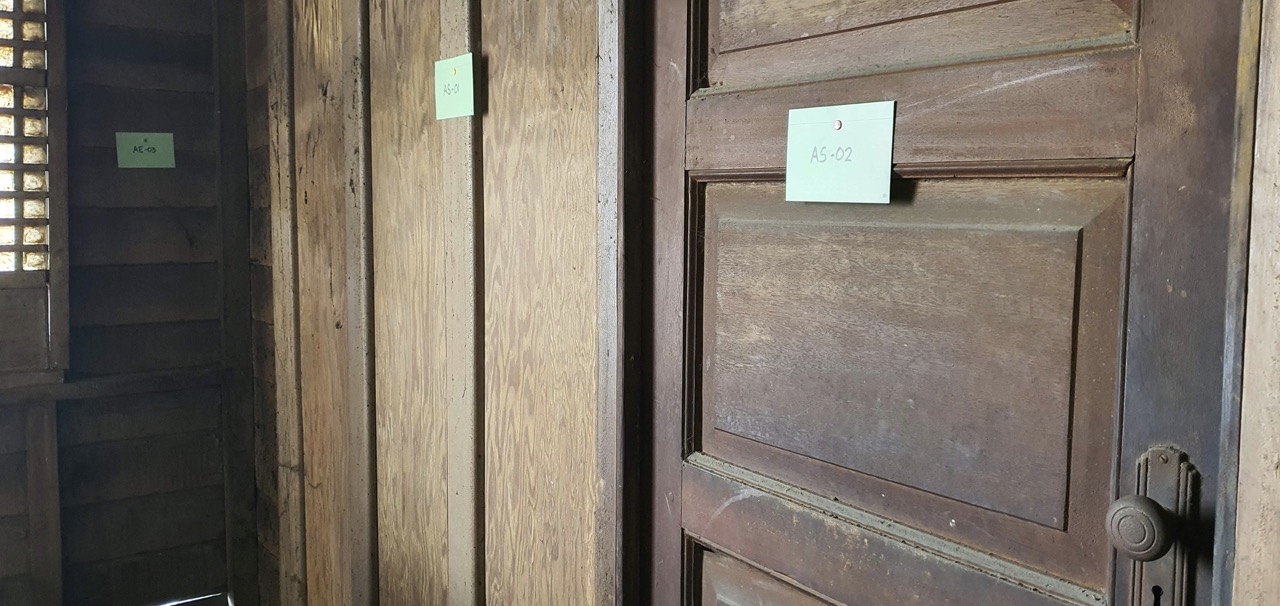

The team collected as many original materials from the old home as possible. They carefully documented windows, metal grills, doors, and wooden components (calado) that were systematically disassembled, tagged, and reassembled piece by piece. These recovered materials were then reused during reconstruction.

Design

They then reprogrammed the original house into a museum. Unlike the usual practice, the layout of the spaces had to align with the plan provided by Arturo Valenzuela. ARC LICO conducted a thorough evaluation of spatial requirements, enabling them to develop a well-integrated plan addressing the authenticity of spatial relationships and the current needs.

The ground floor houses exhibition and multi-purpose areas displaying Valenzuela’s life, along with museum offices and storage rooms that support operations. Visitors are welcomed by a lobby interconnected to an audio-visual room where guests are given orientation. Adjacent to it is an airconditioned exhibit hall that houses artifacts of Valenzuela and a state-of-the-art lights and sounds doll diorama displaying the highlights of Valenzuela’s life.

On the second floor, you will find a main exhibition hall that has two wings dedicated to four other galleries. The lifestyle museum exhibition houses various artifacts from the period integrating audio experience and video mapping projections to enhance the overall museum experience. As per the character of the bahay na bato, wide balconies are on both ends of this level of the museum. The uniform and linear layout with functioning open woodwork and ventanillas allows the entire floor to be passively cooled by the wind.

Again, the structure must create a genuine experience. For example, the wooden floors possess a specific bounce and tactility, done through careful construction that offsets the hardness of the concrete structure. Music of the era wafts through the air. The visual input of old-world materials translate into nostalgia. All of this ties the museum’s historical content together to enrich and inspire the mind.

Furniture

Dr. Lico displays his dedication to planning these spaces through the craftsmanship and curation of every little detail. Filling these spaces required a creative approach that displays an acumen of architecture in its most objective sense. Each object has a historical background and implication that is in line with creating an authentic experience.

The team searched far-and-wide through antique shops, old houses, and even online stores to find the right objects to replicate the furniture of the time. They lovingly repaired and polished old and original pieces such as the dining table, cabinets, lighting fixtures, and ambassador chairs to make them functional again. Valenzuela’s family supported these efforts by contributing even more antique furniture to the museum.

Sourcing furniture from the different eras of Valenzuela’s life, specifically from the 1900s to 1960s, further demonstrates how the home evolves. Additionally, it’s important to consider the objects’ social significance and their reflection of the owner’s status at the time. For example, the museum’s clinic reflects Valenzuela’s background as a public doctor with original items that Dr. Pio used such as medical instruments and beds of the period. Its location relative to the house’s plan is faithful to how the community remembers their visits for treatments.

Honoring Dr. Pio Valenzuela’s Legacy of Service

All of these efforts culminate into the renewal of a previously deteriorating house into a structure that, just like its namesake, serves the people. For Valenzuela’s descendants, it was as if they returned home. Moreover, the community also warmly responded to the project. The locals feel as if the structure has always been a part of their neighborhood. The effort to make the space inclusive, accommodating and inviting to the general public paid off. Bikers have been visiting the museum and even the students use the space as a venue to reenact history for class projects.

The city now benefits from a space that speaks its history, benefits the public, and attracts tourists. As a final touch, the local government of Valenzuela City, through its Cultural and Tourism Office, reinstalled Pio Valenzuela’s bronze statue on the museum grounds. Placed on ground level, rather than on a pedestal, as a symbolic nod to his principles and beliefs of equality.

Having this intimate experience with history helps us appreciate our roots. It instills in us the values and lessons of our leaders during the finest hours of our nation’s narrative. Preserving the memory of Dr.Pio Valenzuela, and other historical figures, through architecture can allow communities to physically express and reclaim their collective experiences to actively engage with their heritage.

Photos are courtesy of ARC LICO & the Public Information Office of Valenzuela City.

Read more: Tabing Bahay: A Modern Take on the Bahay na Bato