Epic Fails: Can you name the architect of these architectural felons?

The thing about landmarks is that they are known for their distinct characteristics, those that enable people to easily see and recognize them. Some of these characteristics even go beyond just recognition and push passersby to take a second look or take out their mobile phones or cameras for a quick shot. These special characteristics, however, are not always those that leave people in awe—they sometimes leave people asking why. BluPrint revisits this article in 2015, which uncovered the monumental design mistakes of 7 world-famous landmarks. Can you name the architect of these architectural felons?

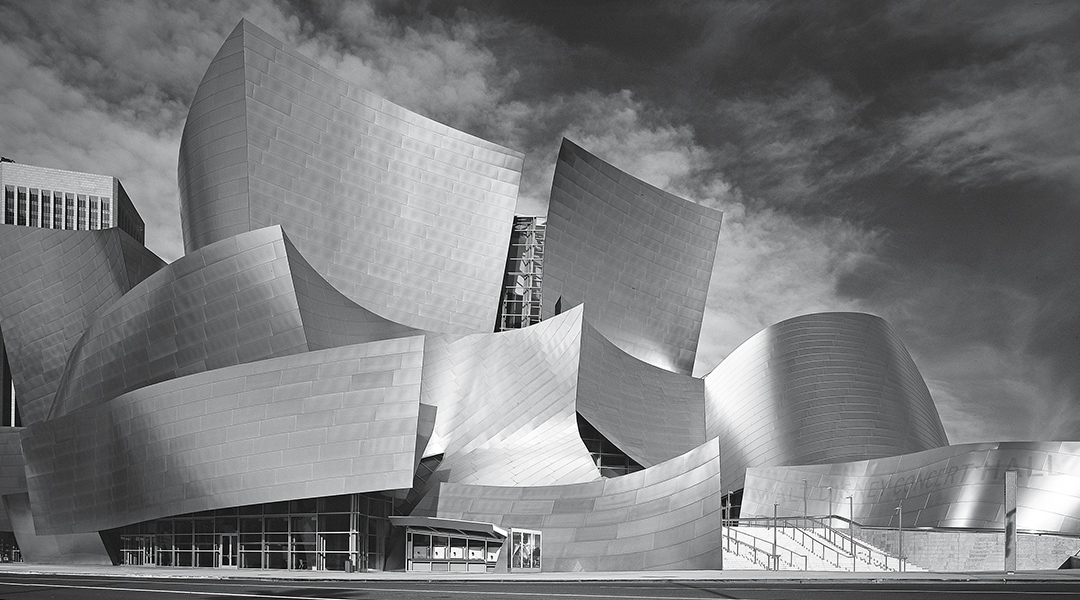

1 Walt Disney Concert Hall

While it opened to much fanfare and critical acclaim for its futuristic design and striking presence along South Grand Avenue in Los Angeles, California, this gleaming beauty hides a scorching beast. The Concert Hall’s shiny stainless steel cladding reflected sunlight onto its neighboring buildings, which brought surrounding temperatures up by 15°F, as well as blinding motorists and scorching sidewalks to temperatures of up to 140°F. The deluge of complaints and potential lawsuits prompted our architect of Guggenheim Bilbao fame to sacrifice the original, smooth mirror-finish of the building, and to have the offending panels sandblasted and matted down in 2005.

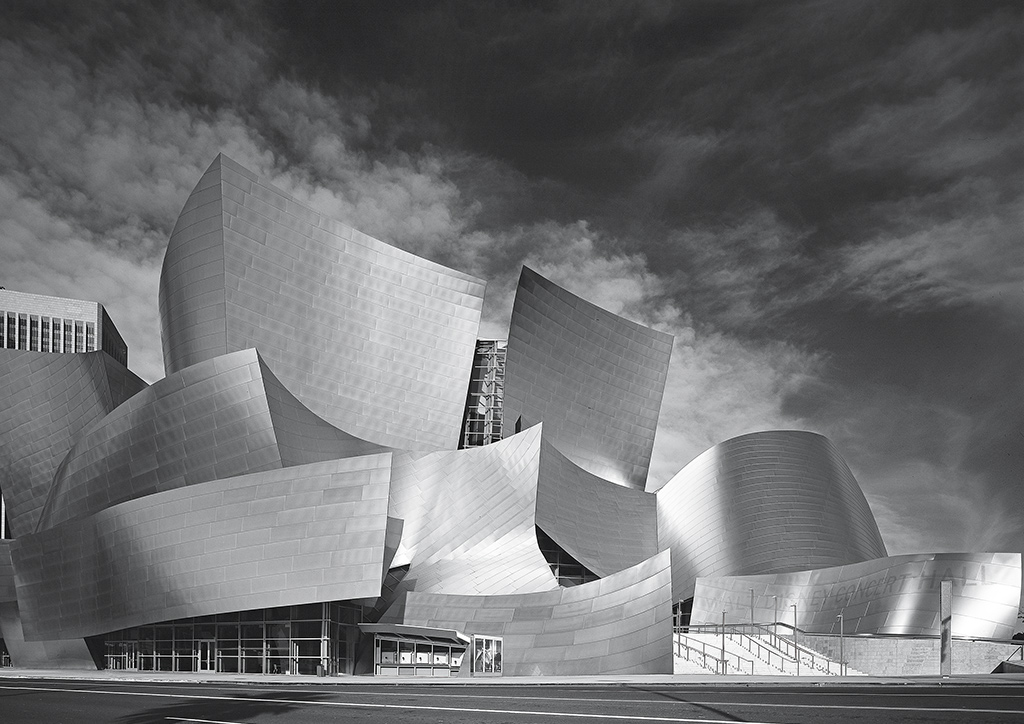

2 Palau de les Artes

Our next architect is no stranger to lawsuits or complaints about his often beautiful but tragically-flawed structures. What makes this case special is that his home city of Valencia had decided to file a case against him for a potentially dangerous defect for the Palau de les Artes opera house; sections of the beautiful trencadis ceramic mosaic tiles that covered the building’s curved façade started to chip off during a bout of high winds, prompting city officials to close off the building until it was deemed safe for the public. This was a bitter pill for the city to swallow, having already spent more than €1 billion for the over-budget City of Arts and Sciences complex, which our architect co-designed, and of which Palau was one of seven showcase buildings. With designs for a leaking winery, a slippery bridge, and a collapsed convention center to his name, our architect can at least breathe a sigh of relief for this one as technical investigations showed the subcontractor to be at fault.

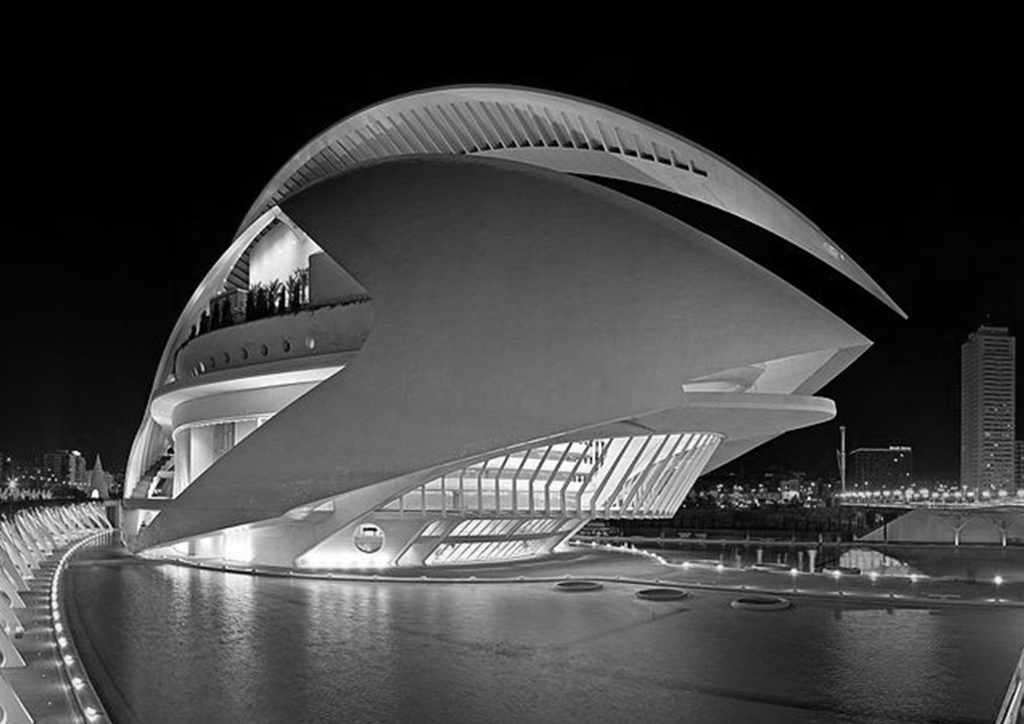

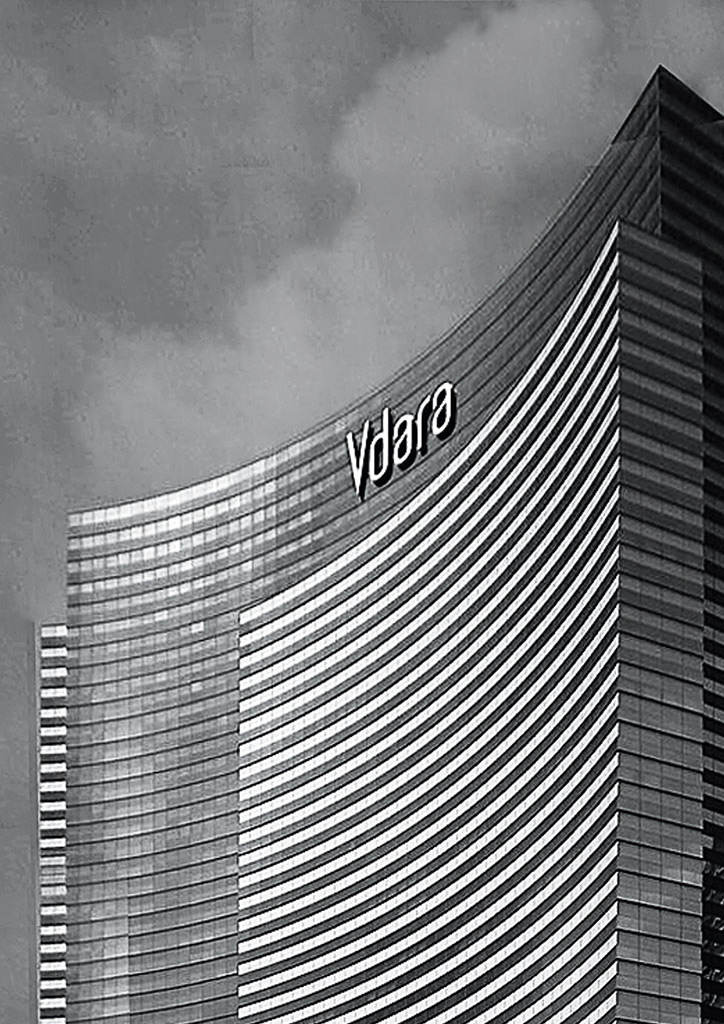

3 Vdara Hotel & Spa

Because of its slim curved form and gleaming glass façade, the Vdara Hotel and Spa was one of several landmark buildings within the CityCenter complex in Las Vegas, a 76-acre mixed-use urban complex by MGM Resorts International in partnership with Dubai World. Equally striking (in not so pleasant terms) is the ‘death ray’ that targets different areas of the pool deck at different times of the day, forming hotspots where getting skin burns and singed hair was a real possibility. The culprit was found to be the building’s concave design and glassy skin that act as a sort of parabolic reflector, beaming sunlight onto hapless vacation-goers and swimmers below. The architect didn’t learn his lesson, apparently, as he faced a similar problem with a skyscraper he designed in London. Talk about déjà vu.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Monumental Design Mistakes in the Philippines: Are we still guilty?

4 John Hancock Tower

A minimalist sliver of glass rising 790 feet over the Boston skyline, the John Hancock Tower is regarded by many as a triumph in architectural design, winning praise for its architect (who was a founding partner of an established architectural firm with a noted Pritzker laureate). However, it was an engineering nightmare. Not long after it was completed in 1968, the tower had passersby and cars running for cover when the entire 500-pound window panes from the tower detached and fell onto the street below. Police had to cordon off the surrounding areas around the building whenever winds picked up to 45 mph. A study was quickly advanced as to what was causing the tower to shed its ‘skin,’ which in the end, necessitated a total re-skinning. The 10,344 windowpanes that covered the tower were replaced with more lightweight and efficient variety. Plywood was used to temporarily block off the missing window panels, which prompted the Boston locals to christen it ‘The Plywood Palace’ when it was being repaired.

5 Stata Center

Described by its architect as looking like “a party of drunken robots got together to celebrate,” the Stata Center opened to critical acclaim in 2004, a flashy replacement for the infamous Building 20 that once stood in its place within the MIT campus. However, three years into its existence, complaints of leaks, cracked stonework, molding, and a possible life threat in the form of ice formation and debris blocking emergency exits, prompted the school to sue the architect and contractor for design and construction deficiencies. Our architect, no stranger to controversies of this nature, blamed ‘value engineering’ and omissions from his designs as the main culprit of the structural defects suffered by the building. In the end, however, the lawsuit was settled, but not before a huge sum of money had been spent for repairs.

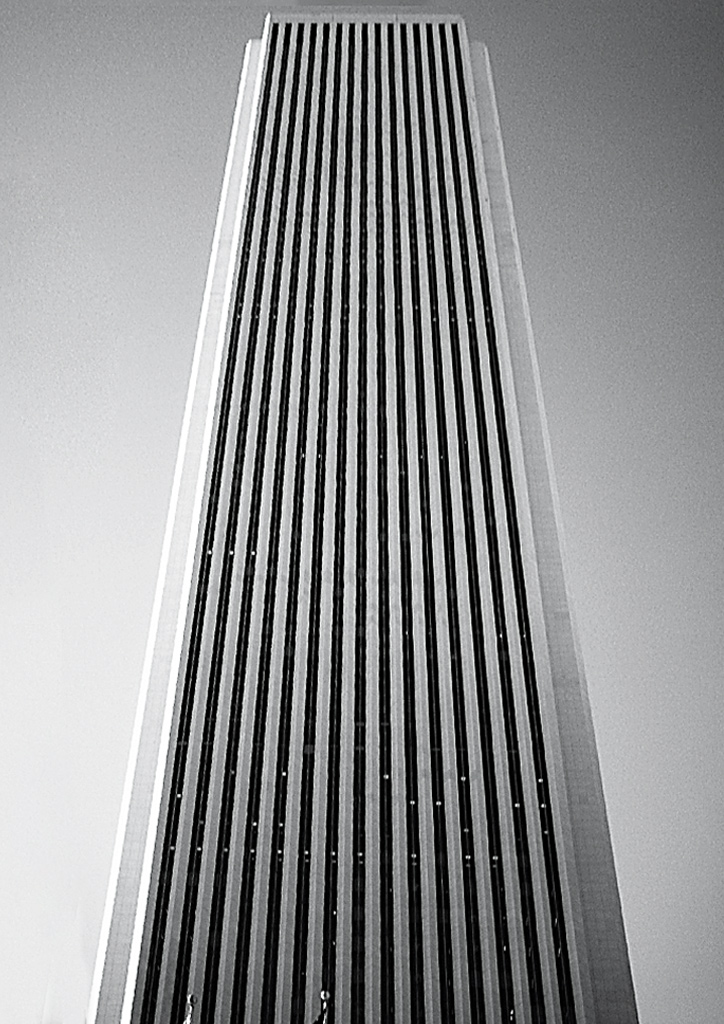

6 The Aon Center

A tragic case of form over function, the Aon Center (Formerly Amoco Building) was a sight to behold with its monolithic, Carrara marble-clad façade. It once held the title of the world’s tallest marble-clad building— until it shed off a 350-pound marble slab just a year after construction, crashing onto the roof of a neighboring building. Cracks and bowing were also found, necessitating a stop-gap measure of adding steel straps to hold the marble slabs in place until a permanent solution presented itself. The solution, however, came with a hair-raising $80M price tag for a total reclad, with Mt. Airy granite used to replace the weak marble. This was more than half the cost it took to build the tower. Findings found the marble slabs used too thin and light for the severe Chicago weather. This major reface awarded the building with yet another record, albeit one it is loathe to keep: the tallest re-cladded building in the world upon completion of its renovation.

7 Citigroup Center

Technically, this building shouldn’t be on our list, but it offers a valuable story on architectural ethics and the dangers of value engineering. Our architect and engineer tandem faced a rather interesting brief in designing the structure for Citigroup’s headquarters; they had to build a skyscraper on a lot also occupied by a church on the northwest, which forbade any form of interference with the church’s structure. The resulting design was a skyscraper on stilts; four 35-meter high stilts held the 59-story building aloft, fulfilling the church’s terms as well as building a striking headquarters for a major bank. However, not long after the building was completed and with hurricane season on the horizon, the building engineer spotted a grievous error in the building design, an oversight that could effectively topple the structure when hit with extreme winds. Value engineering also factored in on the building’s fragile state in that the prescribed design requirements were skimped for a cheaper alternative and without the engineer’s knowledge. It was a disaster just waiting to happen, and one with a potentially enormous body count. Our engineer approached the architect and Citicorp for a solution to rework the cheap bolted joints that held the structure with the welded ones he prescribed. What followed was the stuff of spy and conspiracy novels, where clandestine construction work on the tower was carried out after work hours without the building employees’ knowledge, all to preserve reputations and avoid panic. The remedial work was successfully finished quickly and silently. It wasn’t until 1995 when the truth came out, with many architects and critics slamming our engineer for not making a potentially disastrous oversight public at once.

READ MORE: Name these 7 architects who started out as mentees

This article first appeared in BluPrint Volume 3 2015. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

Answers: 1. Frank Gehry 2. Santiago Calatrava 3. Rafael Vinoly 4. Henry N. Cobb 5. Frank Gehry 6. Edward Durell Stone 7. Hugh Stubbins and William Le Messurier