Industrious Japanese photographer Hiroyuki Oki

Ho Chi Minh City-based Hiroyuki Oki laughs when we ask him how he markets his services online. His Vietnamese wife and business partner An Le joins in the mirth and admits, “We do next to nothing. I actually created his Facebook account for him!” Oki then responds to having too little time to maintain a regular online presence, though it would be false to call his online footprint minuscule. On the contrary, the attention his photos of Vietnamese projects have garnered on international architecture and design websites has cemented his status as the photographer of choice of Vietnamese architecture studios, big or small. He has worked with the likes of world-renowned VTN Architects to the ten-strong studio of Tropical Space and has shot projects as large as university complexes to tiny cheese tart stores. But despite the heft of his photography portfolio, humility pervades the form of this modest man, a humility that is also laid bare in his photos of spaces, which in his own words, “is what I imagine to be what the architect sees.”

From trainspotter to shooting architecture

Hiroyuki Oki’s journey towards his architectural photography career began with trainspotting. “The first time I used a camera was when I was 9 or 10 years old. My uncle bought me a Canon AE-1, which I used to take photos of trains. I traveled a lot when I was a kid.”

This childhood hobby of shooting trains flourished into a desire to want to pursue photography, which Oki followed through when he went to photography college at the age of 20. He admired the works of Sebastiāo Salgado, to name one of his biggest inspirations, and wanted to become a documentary photographer.

A fervent reader of photobooks at the time, he also became enamored by the typological documentation of industrial and utilitarian structures by the influential German photography pair, Bernd and Hilla Becher. “Their work made me interested in architecture. After I graduated, I applied as an assistant for a famous Japanese architectural photographer, Fujitsuka Mitsumasa,” Oki recalls. This stint exposed him to architects of his mentor’s generation wherein he was able to visit buildings designed by Tadao Ando, Osamu Ishiyama, Itsuko Hasegawa, which only whetted the young photographer’s appetite for telling spatial stories.

Falling for Vietnam

Oki first visited Vietnam over ten years ago while traveling across Asia, photographing ordinary peoples’ lives in their daily environment. It was only when Oki began to photograph architecture in Vietnam proper that he realized that it wasn’t the norm for architects to document their projects.

“A publisher in Japan enlisted me to shoot some houses in Vietnam for their magazine back in 2007,” says Oki, “and then I did a few shoots for some architects but the demand wasn’t there yet.” Vietnamese architecture then was already on the cusp of a reawakening, although very few paid attention to contemporary architecture at the time. Oki, however, found an ever-supportive collaborator in An Le, his wife, whom he met in Ho Chi Minh and now serves as the studio manager of his company, Decon Photo Studio.

“He still returned back to Japan to shoot architecture after we met,” says An,

“But then, attention started to pick up here and eventually, he had a lot of local commissions and he decided to move here.”

And while demand was a big part of why Oki decided to make the big move to Vietnam, the burgeoning architectural landscape also excited him. “The architecture scene here is both challenging and exciting. You have these 20 to 30-year-old young Vietnamese architects who are faced with tiny lots and a lot of limitations but their resourcefulness and playfulness have led them to design and come up with new, crazy ideas out of necessity. It’s a struggle for them but the final outputs are often interesting!” Oki observes.

Visual dissection and assembly

We interviewed Oki in a loggia of an old French colonial villa given a second lease of life as an upscale pizzeria, overlooking the historic Ben Thành Market. “I like the view from up here. This is where you see the real Ho Chi Minh,” Oki mentions before the interview began, as he explains his choice of venue for the interview. And indeed, perched on this particular viewpoint, notwithstanding the anachronisms of being served exquisite Italian fare in a French colonial building, one feels part and complicit in the story of the city. You meet its real face, in both its beauty and ugliness, its good and bad, and as both observer and the observed.

“Context is very important to me,” Oki responds when asked about his approach to architectural photography. “Architects first absorb whatever they can when faced with an empty plot of land. They have to visit and feel the atmosphere of the environment around them before they create their designs. With my photos, I try to reverse the process.” Oki proceeds to draw on paper a lot with a house on it. He then draws an arrow pointing to another lot, this time without the house. “I aim for a reversal of the architectural process. I distill the built project until what one sees is the land, the culture, and the story.” When asked why he adopts such an approach, Oki points out, “When you learn the story of the context first before the architecture, only then do design decisions like why the architect chose to use this material or that shape or this form make a lot of sense. In a way, this is how the architect views his project too.” An adds, “His photo shows the architecture the way he believes the architect sees the building. He doesn’t add or force himself into the picture.”

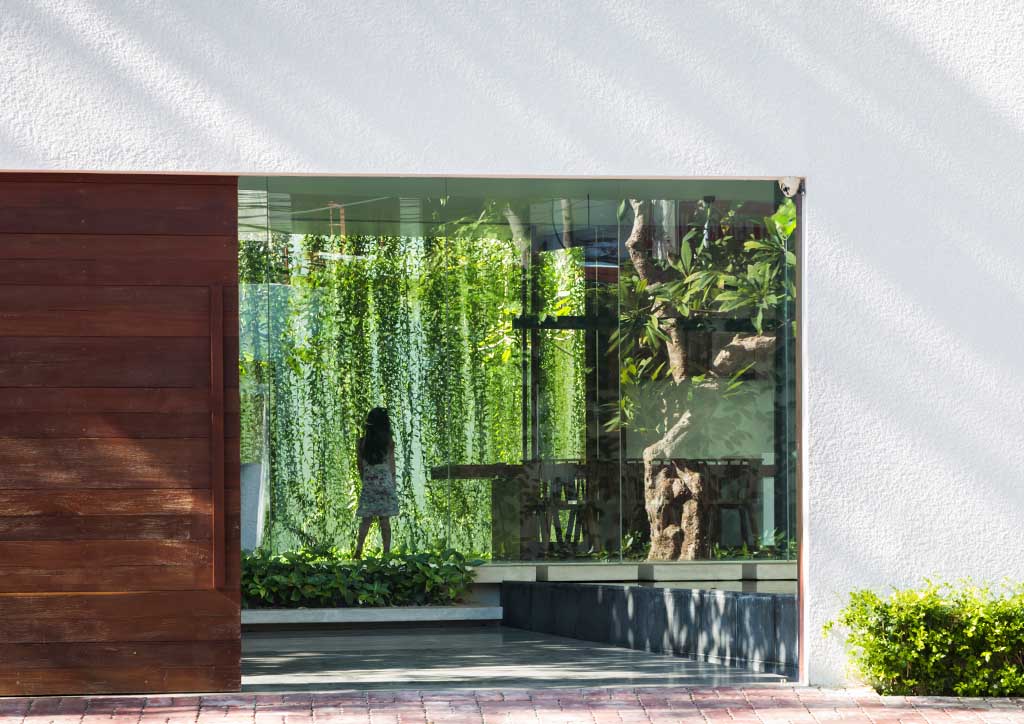

Oki dissects his photography subject in two ways: as both the observer and the observed. This informs the scale, composition, and framing he uses for his scenes. “Whenever I shoot inside, I observe the scene before me but I also imagine myself outside the scene (gesturing above and at a distance from the glass of beverage he has in his hand). It’s like perusing and exploring an architectural model,” Oki explains. After the ‘dissection’ of the site and architecture, Oki strings together scenes in a reassembly. He then proceeds to visually narrate, through his picture selection, the story the architect wants to tell. For Oki, Reading architecture is like reading a novel. “The architecture is the architect’s and the client’s story to tell. A photographer should never be selfish and just shoot objects because they are beautiful, but because they have a role to serve in the bigger picture,” Oki adds.

“Photography is for everyone”

When asked why Oki is the de facto architectural photographer in Vietnam, the architects we met in Ho Chi Minh City attributed this to the enduring quality of his work, dependability, and his indefatigable work ethic. But as our conversation ran its course, we could not help but feel that it really boils down to his sheer passion and a genuine approach for reinterpreting each project’s story that made Oki an indispensable collaborator to have. That he is willing to go to such lengths to tell the true story has even occasionally placed him in great danger. An Le vividly recounts how during a particular shoot, she couldn’t find Oki, and it was only when she looked up at a digger outstretched two stories high that she was able to locate her intrepid husband astride it, camera at the ready.

While his portfolio presents a curated collection of fascinating projects by the who’s who in the Vietnamese architecture scene, Oki doesn’t discriminate with his client list. “I seldom say no to projects, not because I need it but because I am excited at the prospect of learning and telling new stories. Even when the project isn’t amazing or great, there’s a story to find, an angle that can reveal some good attributes, or even hidden beauty.”

Consistent with his desire to tell stories of all stripes, proving that the documentary photographer in him still constantly shapes his work, Oki believes in free access to photography, both as viewer and practitioner. Whereas some photographers of the old establishment might find fault in having their work spread online, Oki welcomes it and relishes getting feedback on his work. When asked to comment about the rise and popularity of novice photographers, aided with the power of social media and its ease of use on advanced gadgetry, the veteran architectural photographer beams, “It’s a good thing because a lot of people see social media and they become familiar with the art of taking photos—ordinary people taking photos, not just professionals. I like this situation. Photography should be open to everyone.”

This article first appeared in BluPrint Special Issue 1 2018. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

READ MORE: Architectural photographers we’re now following online (part 1)