Revirescence, the new exhibit at Artinformal Gallery by artist Jill Paz, exudes a modern-day spin of pastoral paintings that borders on worshipful. It doesn’t just showcase the trees and the flowers, but casts them in a light that transcends the physicality of nature. Paz said that her studies at the Virginia Center for Creative Arts […]

‘Lungsod na Walang Liwanag’: Documenting Poverty in the City

Lungsod na Walang Liwanag is the new exhibit by visual artist Reymark Umpacan. Exhibited at NO Community-run Space at Teacher’s Village, Umpacan’s works revolve around the idea of how people in cities evolve to address poverty.

Specifically, it takes a critical stance on the government’s hands-off approach that forces people to look for other ways to cope with their situations. In Nica B.’s write-up for the exhibit, she exemplifies these traits within the exhibition’s featured works.

“Mas lubos na nasasadlak sa kahirapan ang mga Pilipino, dahil sa kawalan ng nakakabuhay na trabaho at maayos na tahanan, at dahil sa iba’t ibang suliraning panlipunan.” she wrote.

[More Filipinos fall into deep misfortune due to the lack of livable jobs and homes, and other problems inherent in society.]

How We Portray Poverty

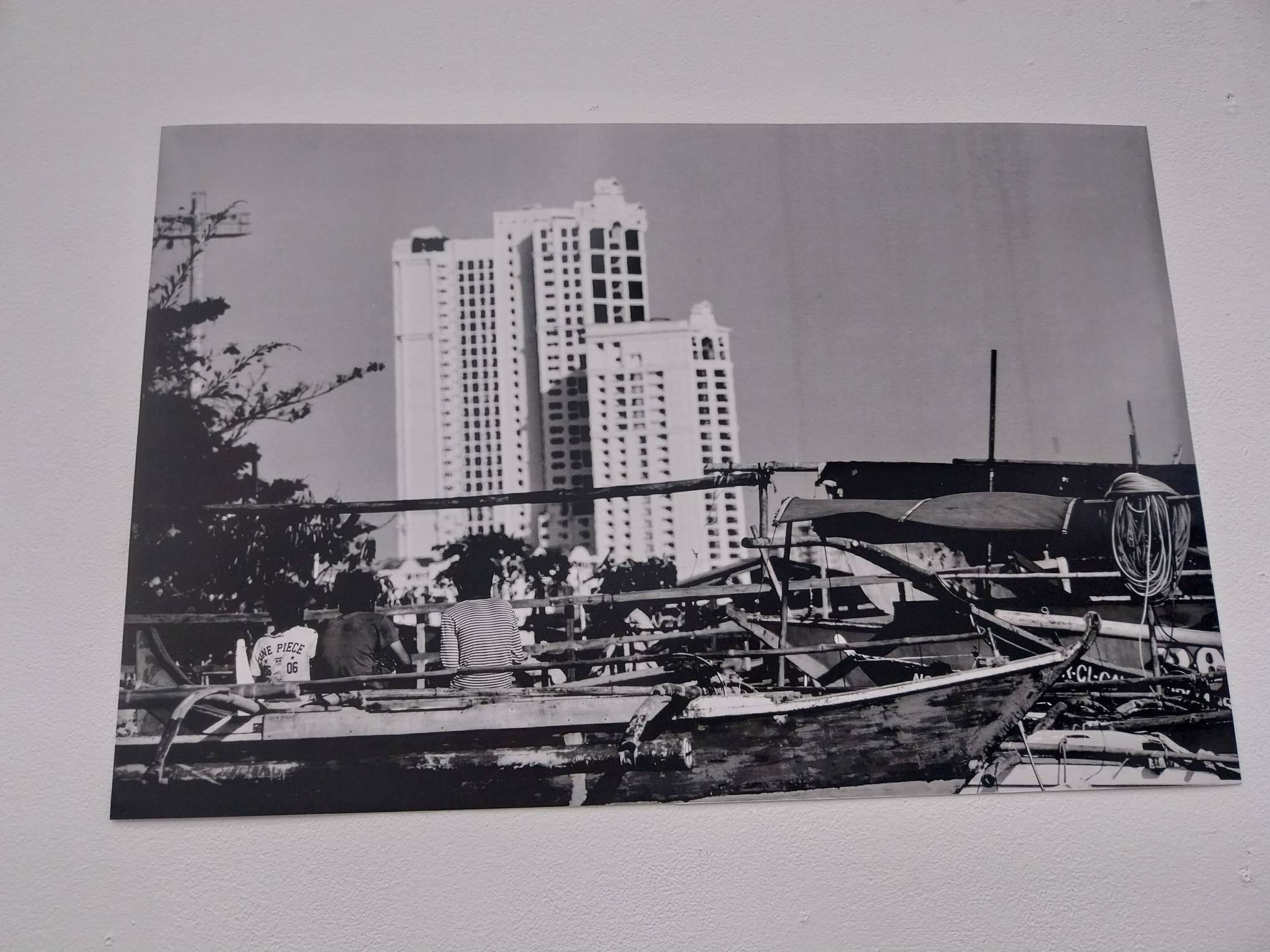

Umpacan’s works present Manila in stark terms, effectively photographing at street level away from the monuments and skyscrapers to see how the people on the ground exist.

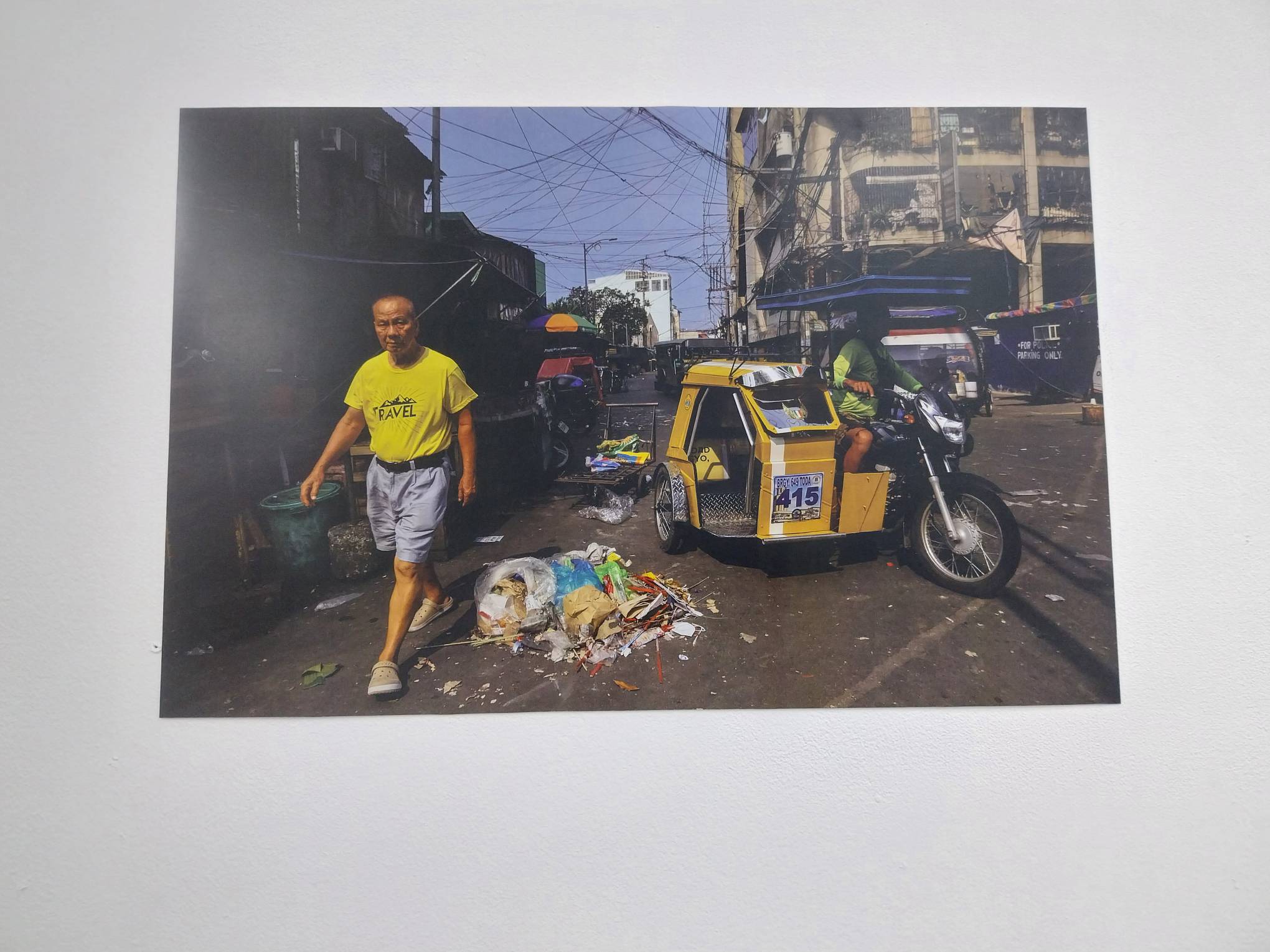

Some photographs show the co-existence of its denizens with the grime of the streets, as in “Pareho ngunit magkasalungat,” where residents and tricycles seem to walk around a small pile of garbage in the middle of the road.

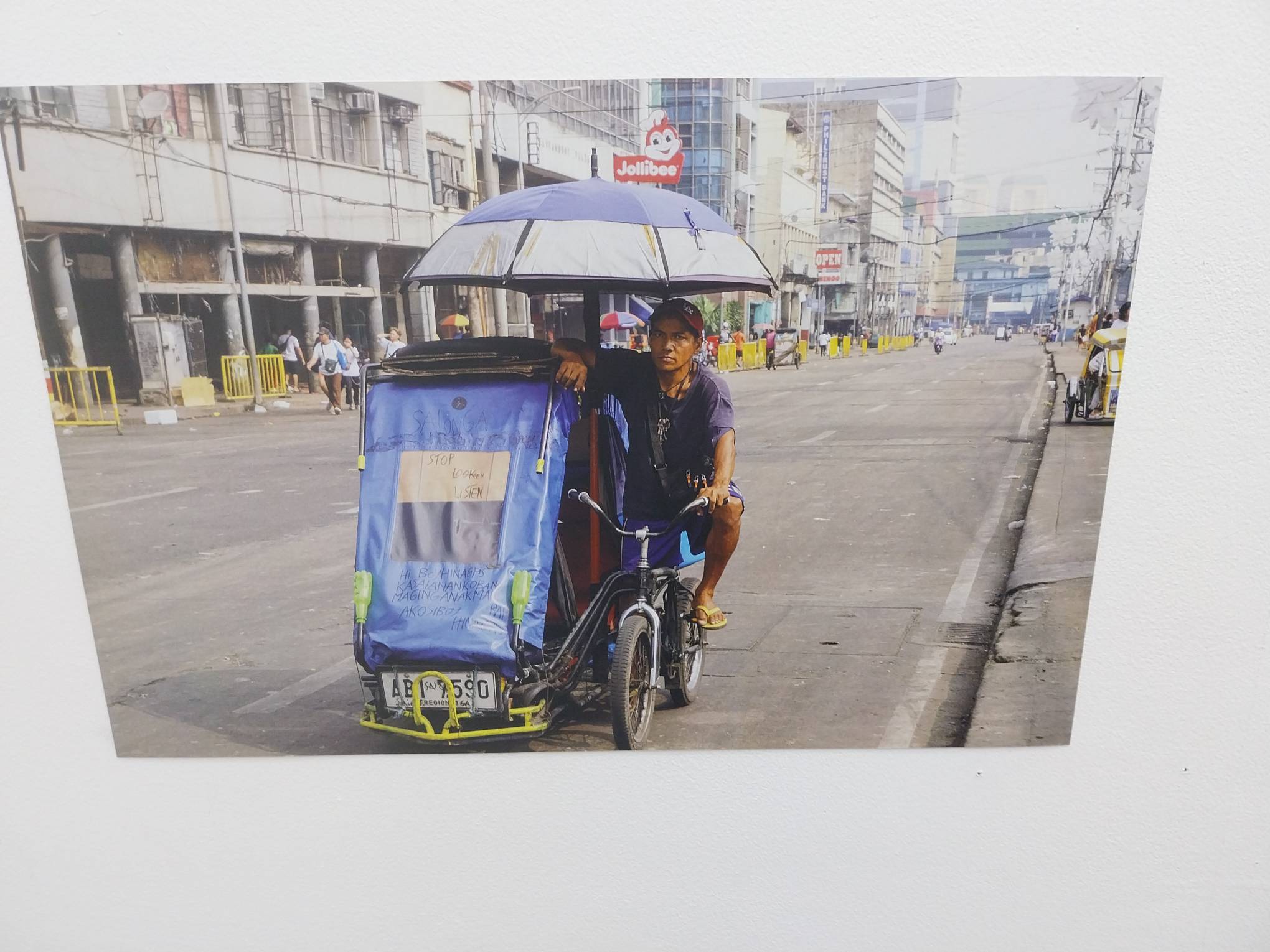

Many photographs here highlight the daily grind of working-class individuals. The best of these, “Hindi mo kasalanan,” shows a pedicab driver with a tired, frustrated look on their face. The derelict pedicab has scribblings on the front, while an umbrella works as a makeshift roof for the driver. It perfectly encapsulates their existence in the periphery, and the lack of help that they get from either the moneyed class or the government.

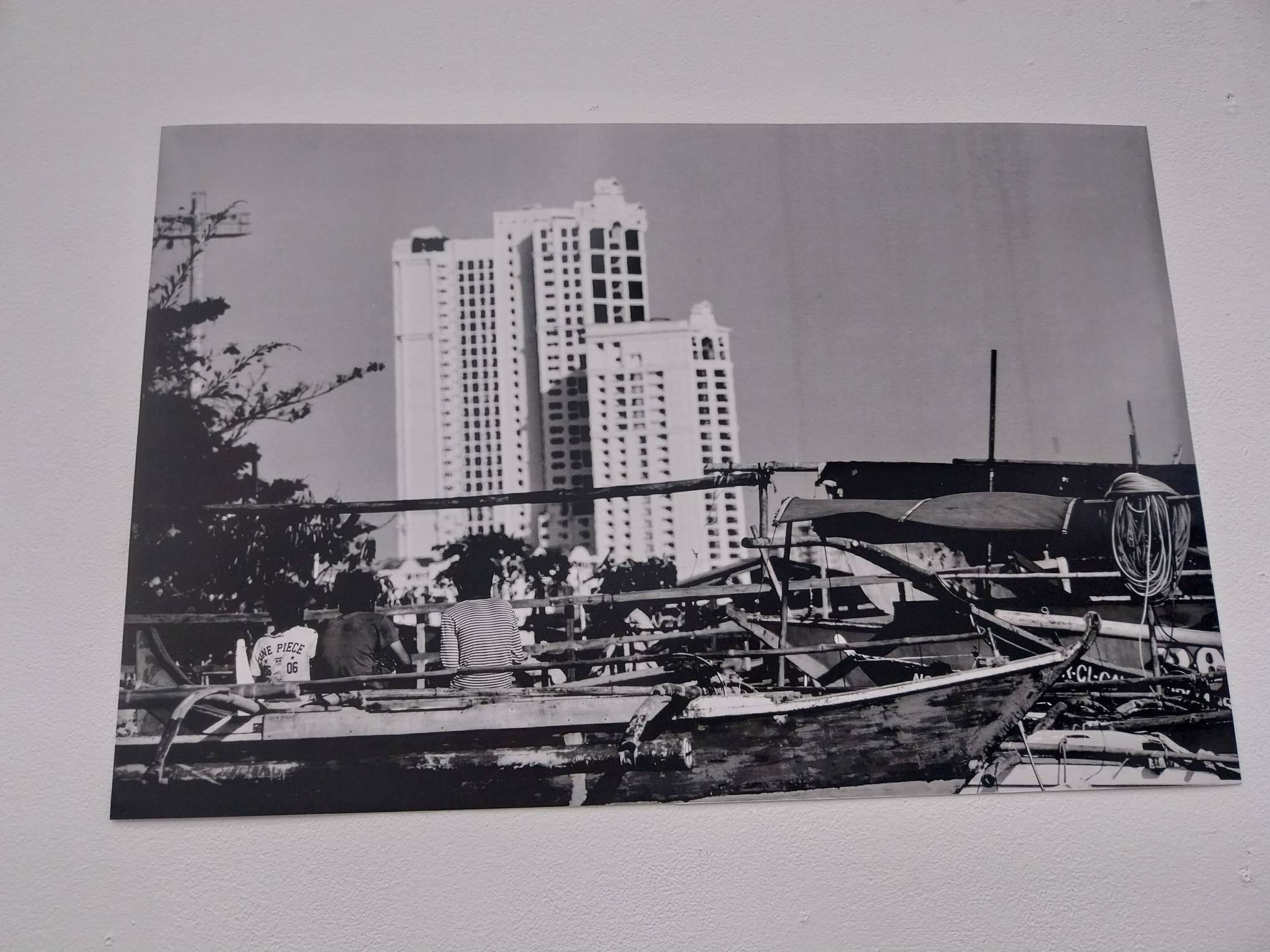

Others, like “Malapit lang pero ang layo pa,” shows children on a ramshackle boat staring at three high-rises in the distance, portraying class and income inequality with blunt imagery. It’s.

The image effectively gives a visual shorthand to the poverty that inherently exists in our system: most people in this country will never have enough money to live in those high-rises as they toil day to day to survive.

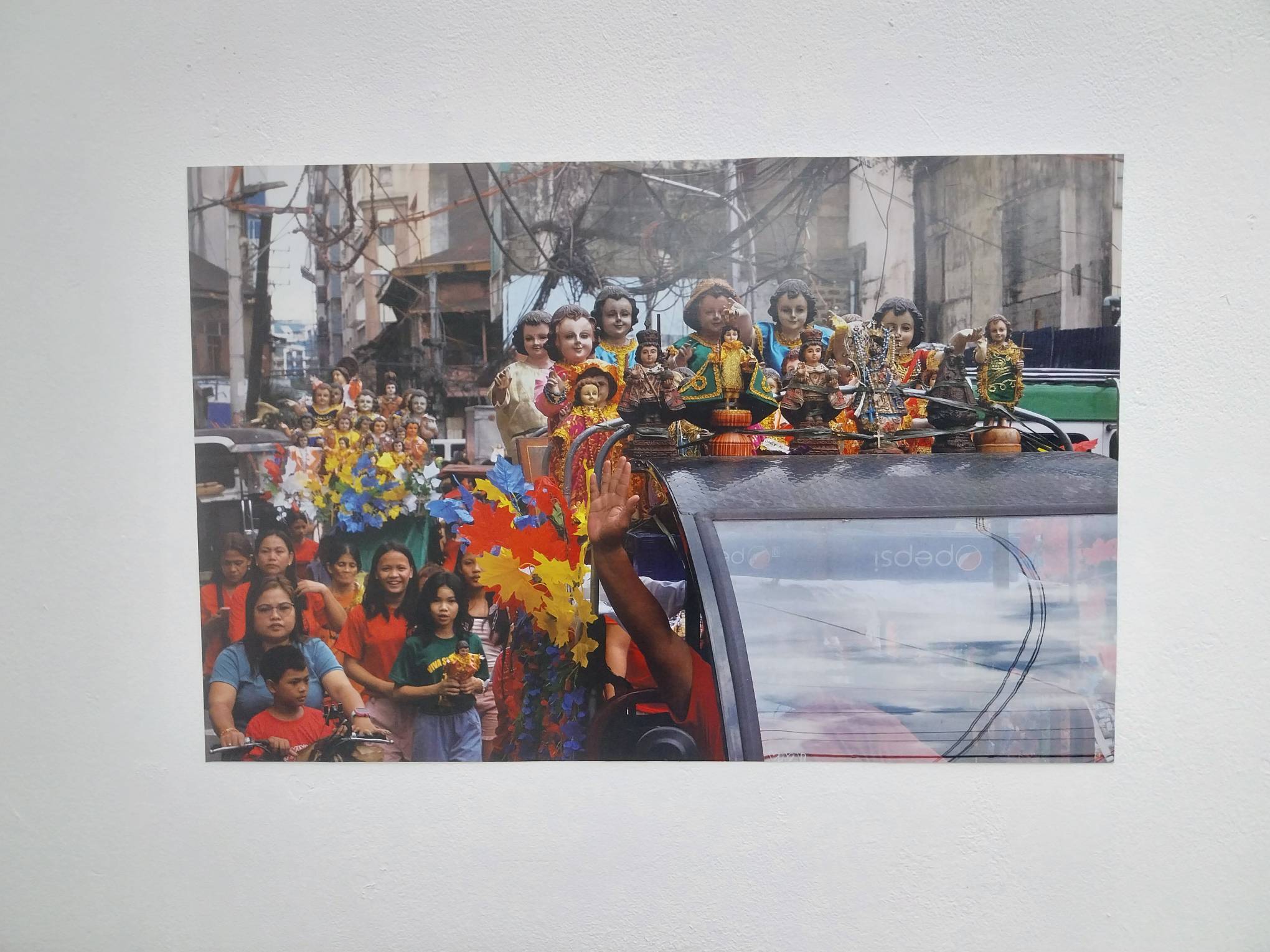

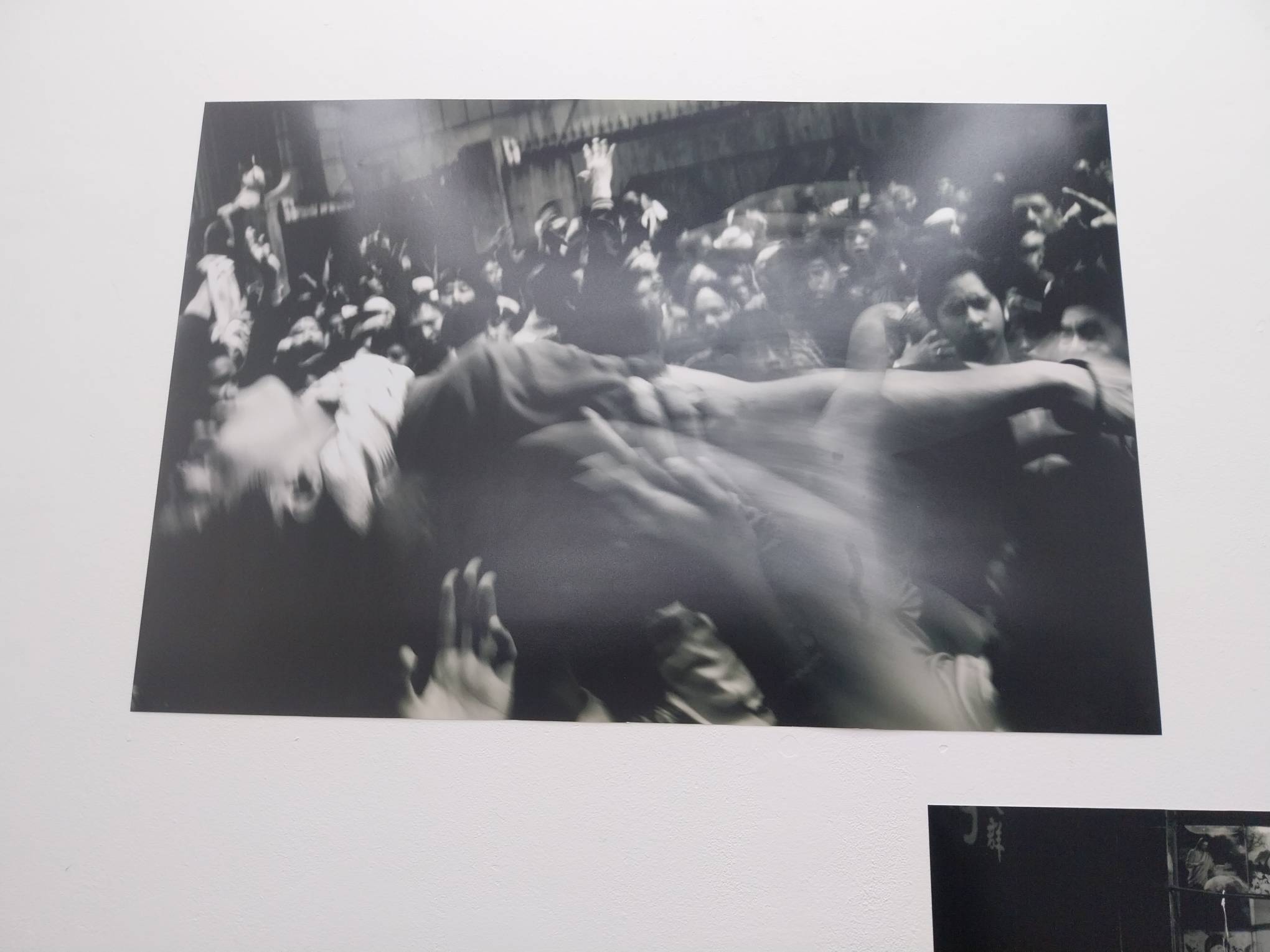

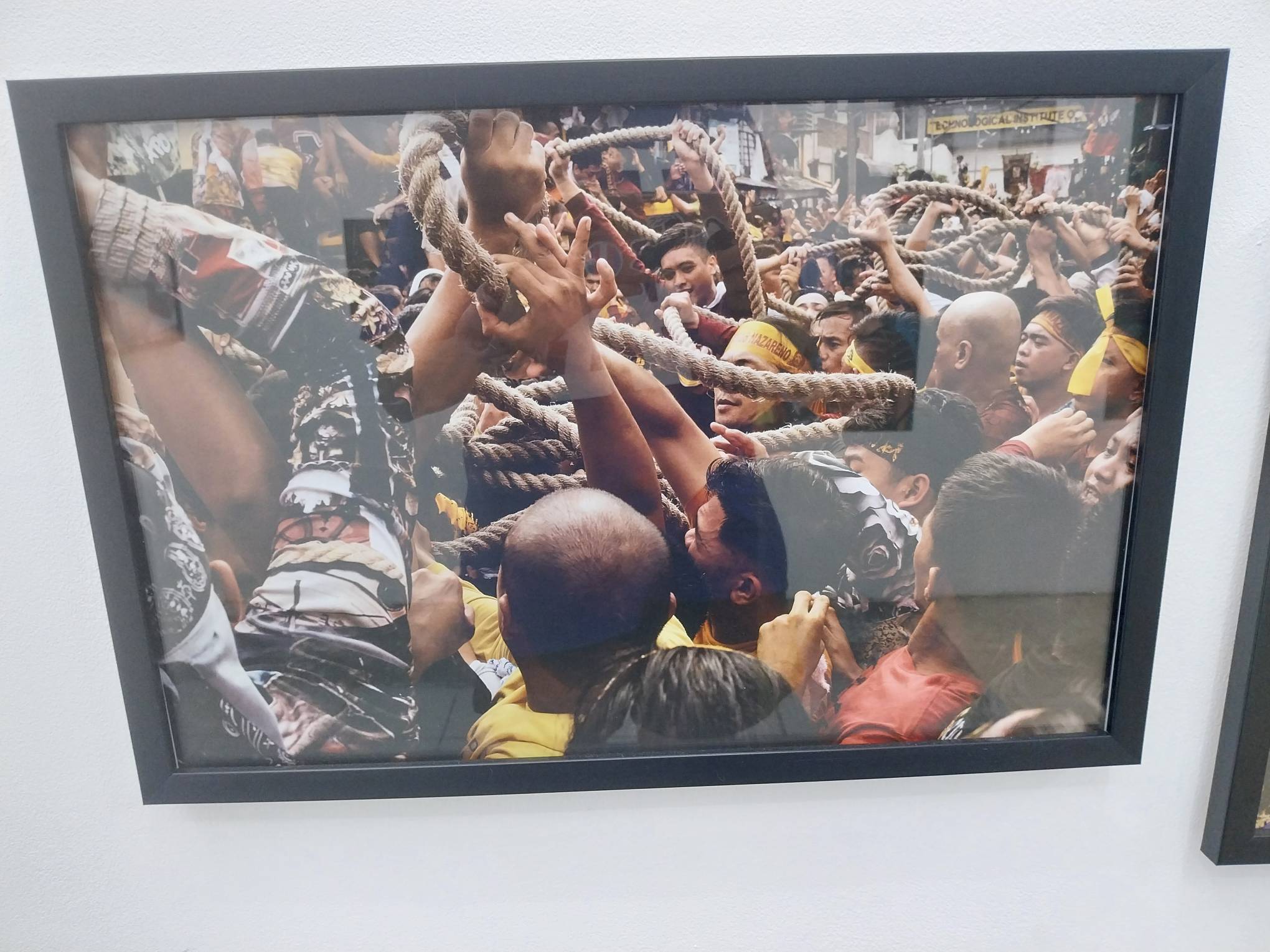

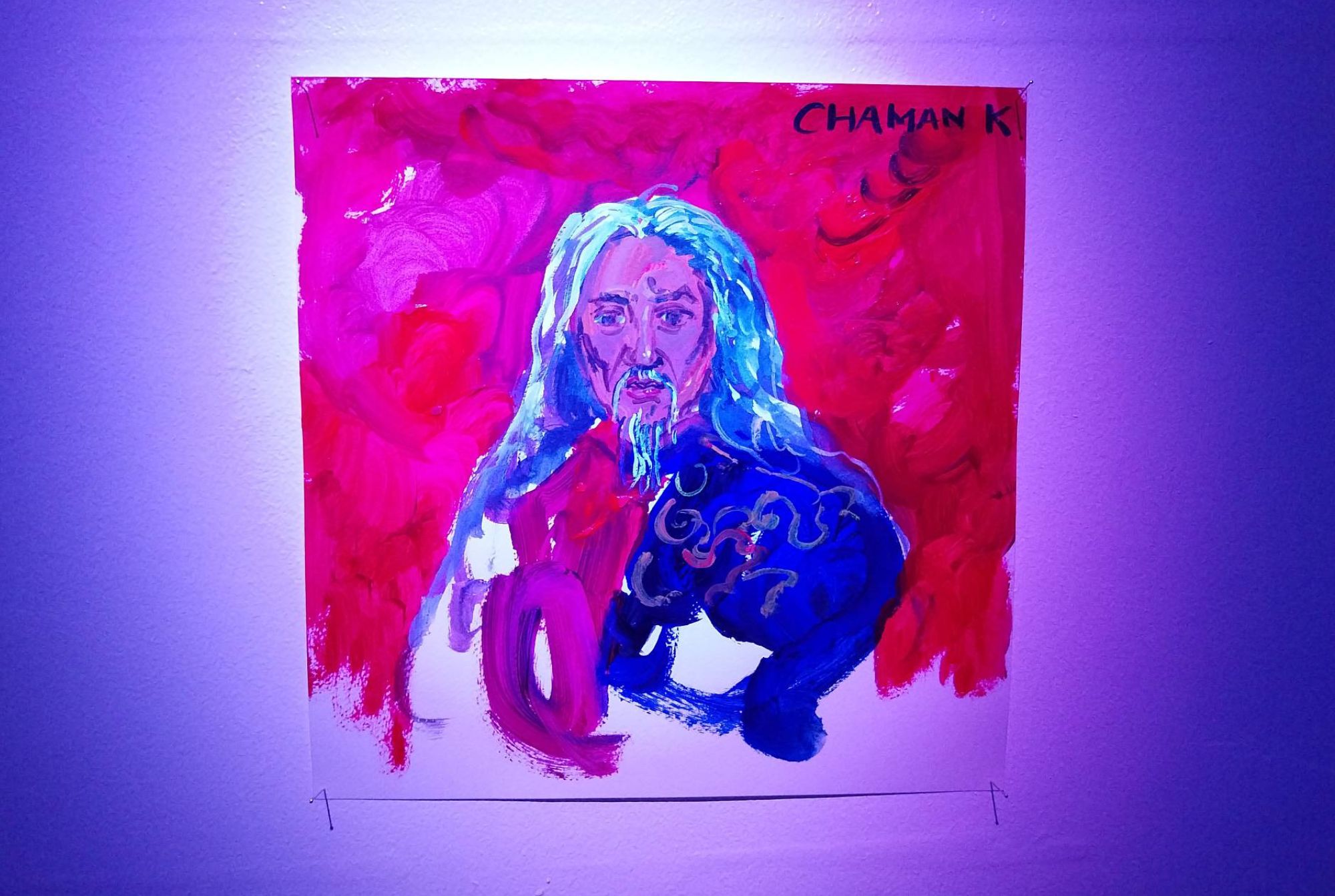

Religious Fervor as an Escape

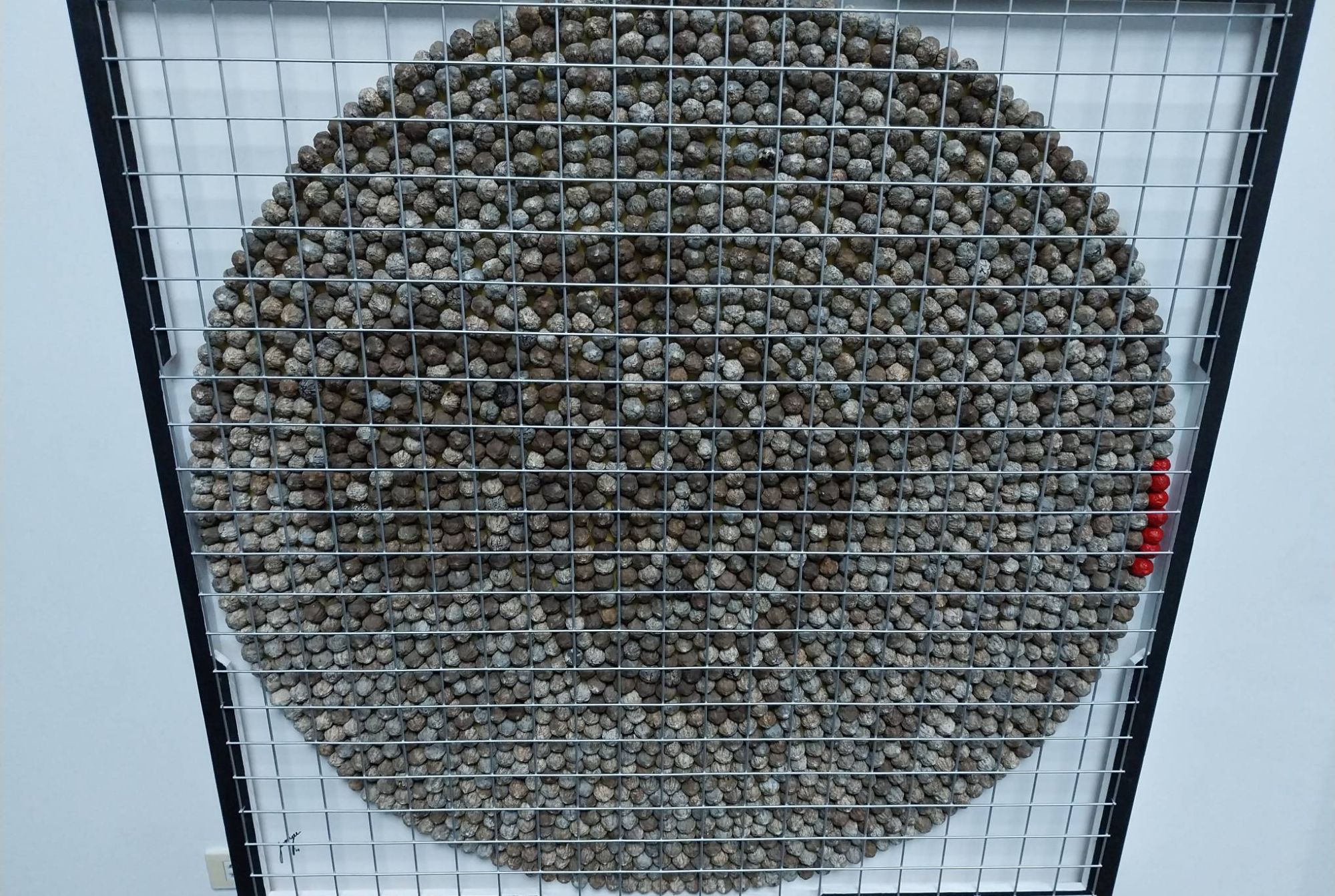

Other photos in Umpacan’s collection illustrate the old “religion as the opiate of the masses” quote in action. Whether it’s photographs of devotees struggling for the rope, or a whole wall peppered with images of Jesus Christ, the photographs are explicit in how they showcase the desperation of the poor to escape their situation through prayer and miracles.

The write-up pushes that assertion forward, that many people find healing in religion when the government has done little to help them out. “Ilan lamang ito sa mga dahilan kung bakit hindi maitatanggi kung bakit karamihan ay kumakapit sa pananampalataya. Dahil ang manalig ay pagbibigay ng pag-asa sa mga panahon na hindi naayon sa kanila ang buhay.”

[This is one of the many reasons why many find themselves grasping towards their faith. Because their faith gives them a period of hope that doesn’t correspond with their life.]

Realities of Poverty

Fiction tends to show poor people in crisis as they attempt to find a way out of their situation. But this exhibit shows a bleaker view of poverty: there’s no hope, only the everyday grind to survive.

It’s people ignoring the trash in the street because nobody in the government is using their funds to move the needle forward. Or people having to use temporary parts for their work vehicles to keep it working functionally. It’s the need to highlight the power of a miracle because only a miracle can get you out of your situation.

Lungsod na Walang Liwanag showcases the quiet desperation of people in poverty, and how they survive even as the world seems to ignore them further.

Related reading: ‘Alburoto’: Recontextualizing Labor Rights as a Women’s Issue