A primer on Muhon — Philippine architecture’s Venice debut

When the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Makati was handed a death sentence last year, no one could do anything to prevent it. Heritage and architecture groups clamored for its preservation but ultimately failed, as the National Commission on Culture and the Arts (NCCA) gave the developer permission to push through with the demolition.

Being the work of a Leandro Locsin couldn’t spare the Mandarin from the wrecking ball, despite a provision in the National Cultural Heritage Act of 2009 that forbids the destruction of the works of National Artists. It’s par for the course in this country, where a toothless law couldn’t protect buildings with historical and architectural value from being destroyed by private developers and even its own government. This in turn alters the skyline of our cities and, more importantly, robs them of cultural markers.

Locsin’s surviving firm, L.V. Locsin Partners (LVLP), could only look on as developers tear down some of their prized architectural works (the Benguet Center in Ortigas, another Locsin masterpiece, met the same fate a few years prior to give way to an office tower, which is yet to come about). These events, however, impelled them to think about what it would take for our modern built heritage to be given greater value by the public. This led them to explore the built environment’s relationship to cultural identity, which they used this as the main theme for their curatorial proposal for the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale 2016. However, their proposal, Muhon: Traces of an Adolescent City, doesn’t set out to identify our cultural identity—it argues that the search for it is more important than actually finding it.

Architecture as memory

Curated by Pritzker Prize winner Alejandro Aravena, the 2016 Biennale’s theme is Reporting from the Front, which urges the national participants to offer new perspectives on a wide range of societal issues.

The LVLP team, led by principal Leandro “Andy” Locsin, Jr. and project architects Sudarshan Khadka and JP dela Cruz, initially wanted to tackle disaster resiliency and social housing for their curatorial proposal. But feeling that these will be covered by other participants, they elected to pursue heritage and identity for their proposal, a topic close to the firm’s heart following the recent demolition of the Mandarin Oriental.

LVLP’s proposal explores the theory that the rapid creation and destruction of a city’s built heritage precludes the formation of cultural identity. Their main argument is that our built environment informs our identity as a people, and vice versa—a synergy that is palpable in heritage cities such as Florence and Kathmandu, the firm’s main inspirations for their proposal.

READ MORE: The magnificent restoration of the National Museum of Natural History

The team takes particular issue with the treatment of post-war buildings, most of which are under 50 years old, putting them outside the reach of the heritage law. With our country’s rapid pace of development, several modern structures with historical and architectural value are being mowed down to make way for new ones. LVLP argues that this constant cycle of destruction and rebirth causes us to lose more than just aesthetically pleasing works of architecture. “We believe that architecture is a form of memory,” says Khadka. “By destroying buildings that belong in a certain era, you’re destroying the memory of that time. And without that memory, you lose that sense of identity. You have nothing to connect with.”

This is particularly resonant for a megalopolis such as Metro Manila, whose urban landscape is constantly changing ever since the end of World War II, and is currently growing into a mega-city. Because of this, the LVLP team chose the city as the focus of their exhibit, referring to it as an “adolescent city” whose identity is still in flux.

To build is to exist

As mentioned earlier, the exhibit’s aim is not to dictate or impose what Filipino cultural identity should be, but rather to incite us to search for it by understanding ourselves through the built environment. The team’s concept revolves around the muhon, a Tagalog term for boundary stone or landmark that people in ancient times used to stake their claim in the universe. “The creation of a monument is the most primitive act of confirming one’s existence,” says Khadka. “We feel that some of our built heritage, whether it’s a building, park, or infrastructure, are modern muhons.”

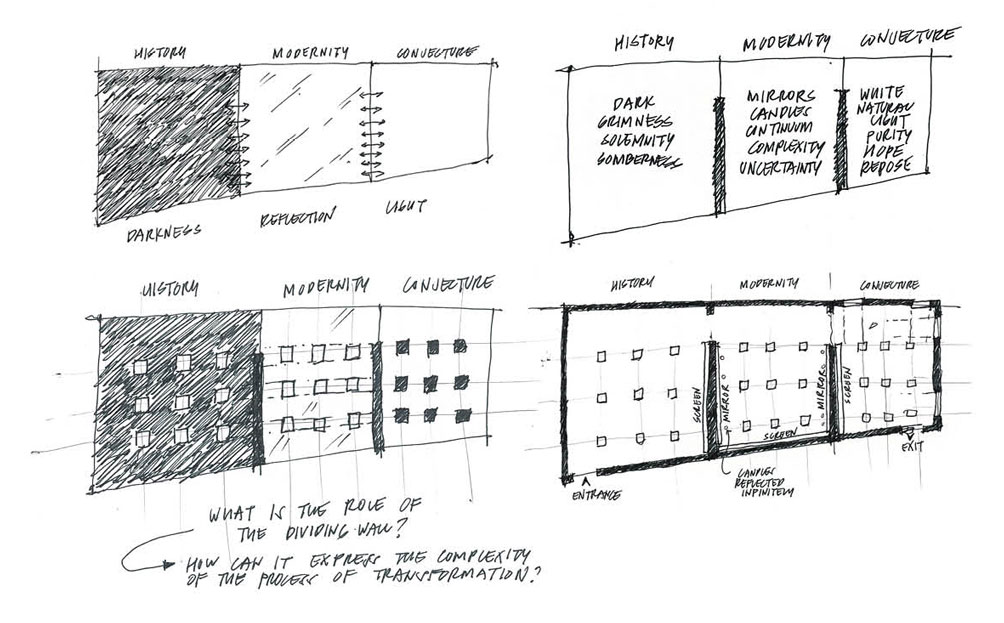

As curator, the LVLP team wanted to create a context where the value and potential of muhons could be explored and analyzed. The venue for the exhibit is a set of three adjacent rooms (or chambers) in the Palazzo Mora located at the historic center of Venice, each measuring 47 to 55 square meters. The idea was to make visitors see how a muhon could evolve and adapt over time, and in turn see the value and potential of preserving it for the future.

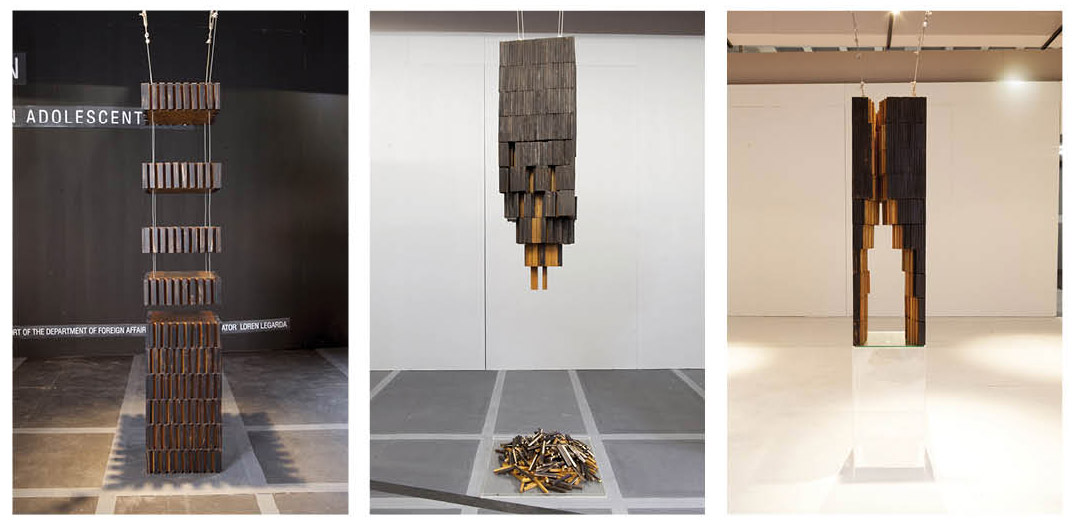

To demonstrate this, the team appointed nine designers—six architects and three contemporary artists—and asked them to choose from a shortlist they compiled of buildings and sites under 50 years old, all within Metro Manila. Each designer was tasked to create three abstractions of their chosen building/site that correspond to its original state, current condition and projected future.

These three time frames serve as the “themes” for each chamber in the exhibit—History, Modernity and Conjecture. In each chamber, the abstracted models of the muhons are arranged in a 3×3 grid, forming a mini-picture of Metro Manila as an evolving city. Visitors are first ushered into the History room, then progress to the Modernity and Conjecture rooms.

What makes the exhibit interesting is that the focus isn’t on the models as solutions for the built heritage they’re representing—visitors are meant to trace the evolution of each model, and see the personal reflection and journey that the collaborator went through in the process. “The idea is, understanding a muhon in terms of its past, present and future helps one appreciate its value as a signifier of cultural identity,” says Khadka.

Relevance

Dominic Galicia, one of the jurors who deliberated on the submitted proposals, notes that LVLP’s Muhon is a timely and relevant exhibit that incites discourse about the value of our built heritage, something our local governments and developers ignore. But more than just inciting discourse, it promotes the possibilities of reuse and adaptive reuse for some of Metro Manila’s old buildings.

The designers, however, do not pinpoint a specific solution for their muhons—they merely abstract or distil the essence of their chosen building or site, in order to discover its value (or lack thereof). As an example, Eduardo Calma chose the Philippine International Convention Center (PICC) by Locsin as his muhon due to its strong impression on him as a child. He then “extrudes” the volume of the PICC through his three abstract models to create a commentary on the banality of modern architecture (“Buildings today are just extrusions of their properties,” he says). For Mark Salvatus, he uses the hardware store as a metaphor of his chosen muhon, Binondo. The metaphor seeks to illustrate the “composite” identity of Binondo, which has come to be known as the country’s “Chinatown” because of the numerous Chinese-Filipinos that made it their home.

There’s something poetic about LVLP’s Muhon being exhibited in Venice, a city known for taking great pains to protect its heritage. In such a setting, the message of the first Philippine exhibit at the Venice Architecture Biennale becomes even more pronounced—a built environment’s cultural identity is vital to forming the identity of the people inhabiting it. But LVLP’s exhibit doesn’t just sing the same old tune of preserving heritage for the sake of preserving it–it helps open our minds to the possibilities of what our built heritage could be in the future, in turn preserving the memories of our cities for future generations. ![]()

MUHON DESIGNERS

LVLP selected nine designers (six architects and three artists) to create muhons for the pavilion. The firm surveyed over 50 buildings and sites within Metro Manila that they felt had architectural and cultural merit, for the designers to choose from. The objective was to explore the significance and evolution of each muhon, in order to create three models that represent History, Modernity and Conjecture. “We selected people who have a track record of being contemplative and open to the ‘art’ side of architecture, and have opinions on the issue tackled by the exhibit,” says dela Cruz. “We also chose contemporary artists to help us gain a wider perspective, because they have stronger connections with the place they work in.”

Architects:

Makati Stock Exchange Building – LIMA Architecture

Mandarin Oriental Hotel – Jorge Manuel Yulo

Pasig River – C|S Design Consultancy

Philippine International Convention Center (PICC) – Ed Calma

Ramon Magsaysay Center – 8×8 Design Studio

Coconut Palace – Mañosa & Co.

Artists:

Binondo Chinatown – Mark Salvatus

Pandacan Bridge – Tad Ermitaño

Rizal Park – Poklong Anading

This article first appeared in BluPrint Vol 3 2016. Edits were made for Bluprint online.

Photographed by Ed Simon