A bahay kubo-inspired house furnished with abstracts

“I feel betrayed,” says architect Oscar Peñasales’ wife. Like many Filipino nurses, the wife’s dream to work abroad. She had been traveling back and forth with her husband to find a job in the US without success. When the couple went back to the Philippines in 2006, Peñasales’ was hired to design his first big project—the Plazuela de Iloilo, a mixed-use development with a convention hall and hotel. This lucky break prompted Peñasales to start building their home. His plan was to use his fee from the Plazuela to fund the construction of his house.

“I wasn’t excited. I felt building this house was intended to put a stop to my dream of working abroad,” the wife continues. To her further dismay, she found her husband’s design for their future home so grotesque she refused to leave the car whenever they visited the construction site. “My first reaction was, ‘What kind of design is this?’ I couldn’t understand the shape!” she says. For months on end, the couple hardly talked. Little did they know the house would eventually change their life for the better, especially when the lucky break turned out to be a bad one. In the middle of design development, the owners stopped the project. The original brief was pared down to a simple commercial strip, for which they hired Manila-based Palafox Associates instead, and Peñasales was paid only up to the extent of his work on the original project.

Not one to give up on his dream home, Peñasales applied for a housing loan and was approved a meager 1.6 million pesos, hardly enough to build a two-story house in a posh subdivision. “I had no project and no money. I had to fit our budget for this house and pay the tuition of my daughter,” he recalls. He had intended to use recycled materials for the house but without the money he was counting on, he now was obliged to be even more creative to cut costs.

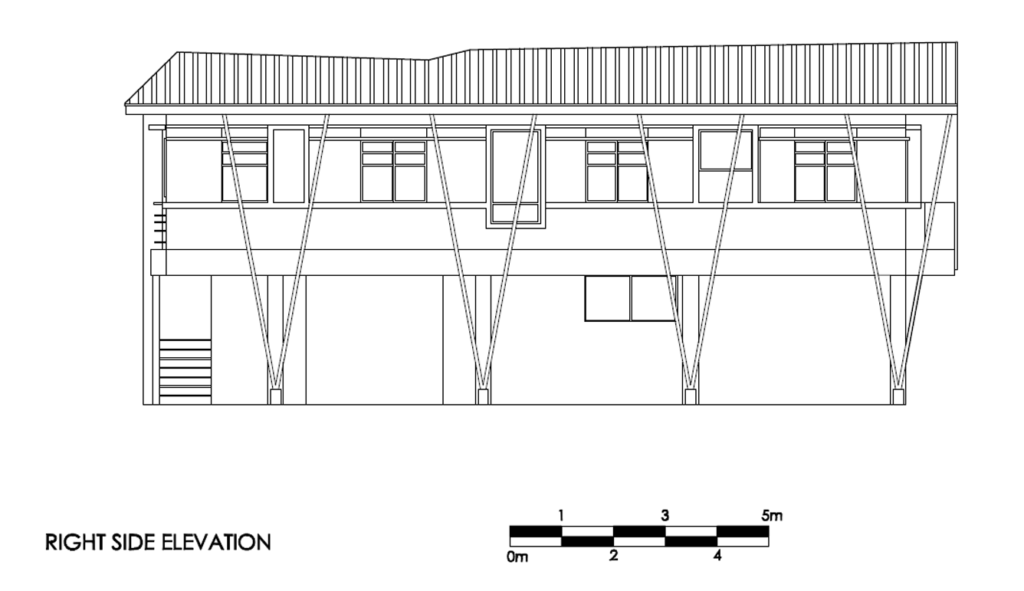

Except for the ceiling, all the wood used in the house is recycled formwork. “That’s why the wood widths vary. If I cut them in the same size, there would be lots of wastage,” says Peñasales. The door jamb of the main door, for example, is made from the formwork used in the construction of an old airport runway. The floor was supposed to be all wood, but he ran out of lumber and couldn’t afford tiles, so he for the cheaper black oxide concrete. Concrete walls were kept bare or finished with skim coating. He used recycled glass for jalousie windows and sliding windows.

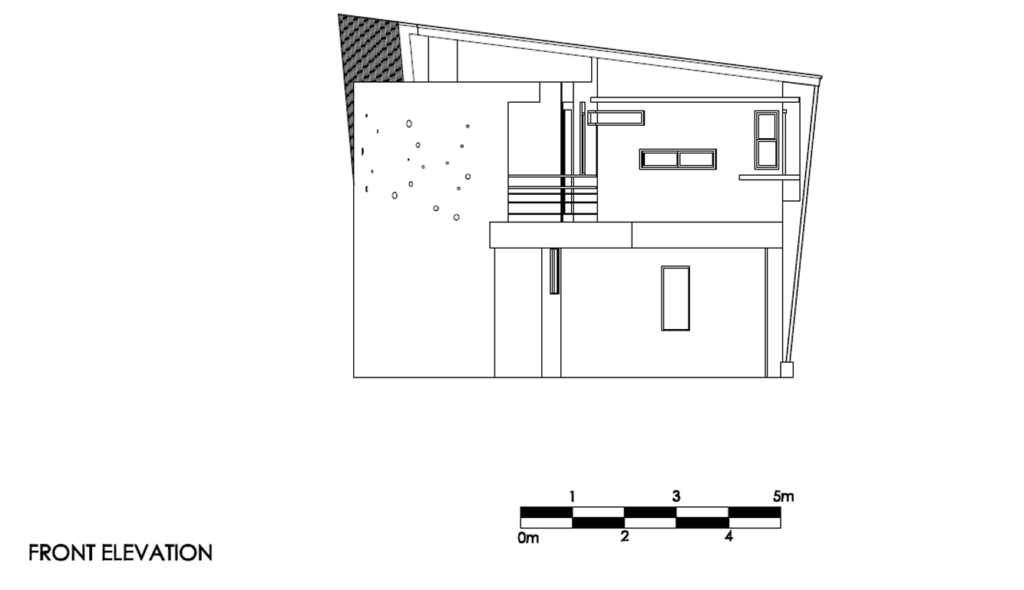

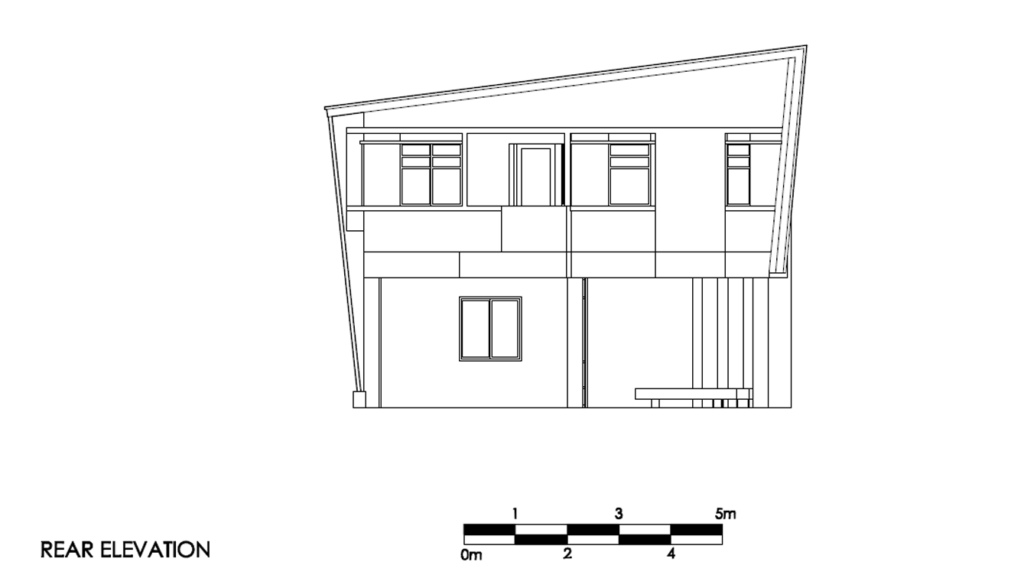

The program of the house, according to Peñasales, is inspired by the bahay kubo. The living areas are on the second floor, supported by steel stilts, while the ground floor serves as a silong which he used as a furniture workshop. The wife, however, complained of the dust and noise so now the space functions as a garage. Beside it, Peñasales built a man cave housing his office and an art studio where he paints on weekends. His artworks are displayed in every nook and corner of the house. The house served as an outlet for his artistic inclinations and frustrations. In his book, Istilo: Pocket Guide to Architectural Styles in the Philippines, architecture historian Gerard Lico classified the house as deconstructivist. Its unconventional geometry, skewed shapes and angles, and disregard for symmetry fit the characteristics of the 1980s architectural style. Peñasales is happy with his design but it was an acquired taste for his wife. “I never had the excitement every wife has for her first house because I wanted a traditional design,” she says. When they moved in, curious neighbors would come and ask if they could have a peek inside what they thought was an unfinished house.

The couple has grown to love the attention the house is getting from their neighbors and friends. “Architecture practice in the province is different from that in Manila.” Ilonggos are very conservative and have different taste. When they buy paintings, they prefer rural settings and seascapes over abstracts. For houses, they prefer French villas and Mediterranean homes,” says Peñasales.

Peñasales admits that the house gets uncomfortably hot especially during the summer, hence the need for air-conditioning units in all the rooms except the bathrooms. Many of the windows are small and not positioned to allow effective cross ventilation. The eaves, especially outside the living area, are not deep enough to shield the interiors from sun and rain. During the wet season, the booming sound of rain pounding on the roof drowns our conversation, television, and music on the second floor. “I thought the galvanized aluminum insulation would be enough. It does insulate heat from the roof but not the sound of rain,” says Peñasales. He also confessed that in addition to rain spattering through the windows, rainwater accumulating in the terrace enters the living room. The problem could have been avoided had the living room floor been made higher than that of the terrace, or if the terrace floor had been constructed at a slight decline to direct water to drainage away from the living room door.

In retrospect, he considers the house his big break. It won the grand prize in the Metrobank MADE Architecture competition in 2011. Because of the publicity, he says he was able to get more projects and sustain a thriving practice. “It launched my career. I thought it would break me. Ito pala yung break ko,” he says with a laugh. ![]()

This article first appeared in BluPrint Vol 5 2016. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

Photo

READ MORE: Edith Oliveros – the Grand Dame of Philippine Interior Design