‘Warm Bodies’: Creating Empathetic Art in an Unkind World

Warm Bodies: Defending the Right to Dissent is an exhibit assembled and curated by the Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP). In response to the recent visit of Irene Khan, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, the exhibit was held at the UP College of Fine Arts Gallery from January 26 to February 21.

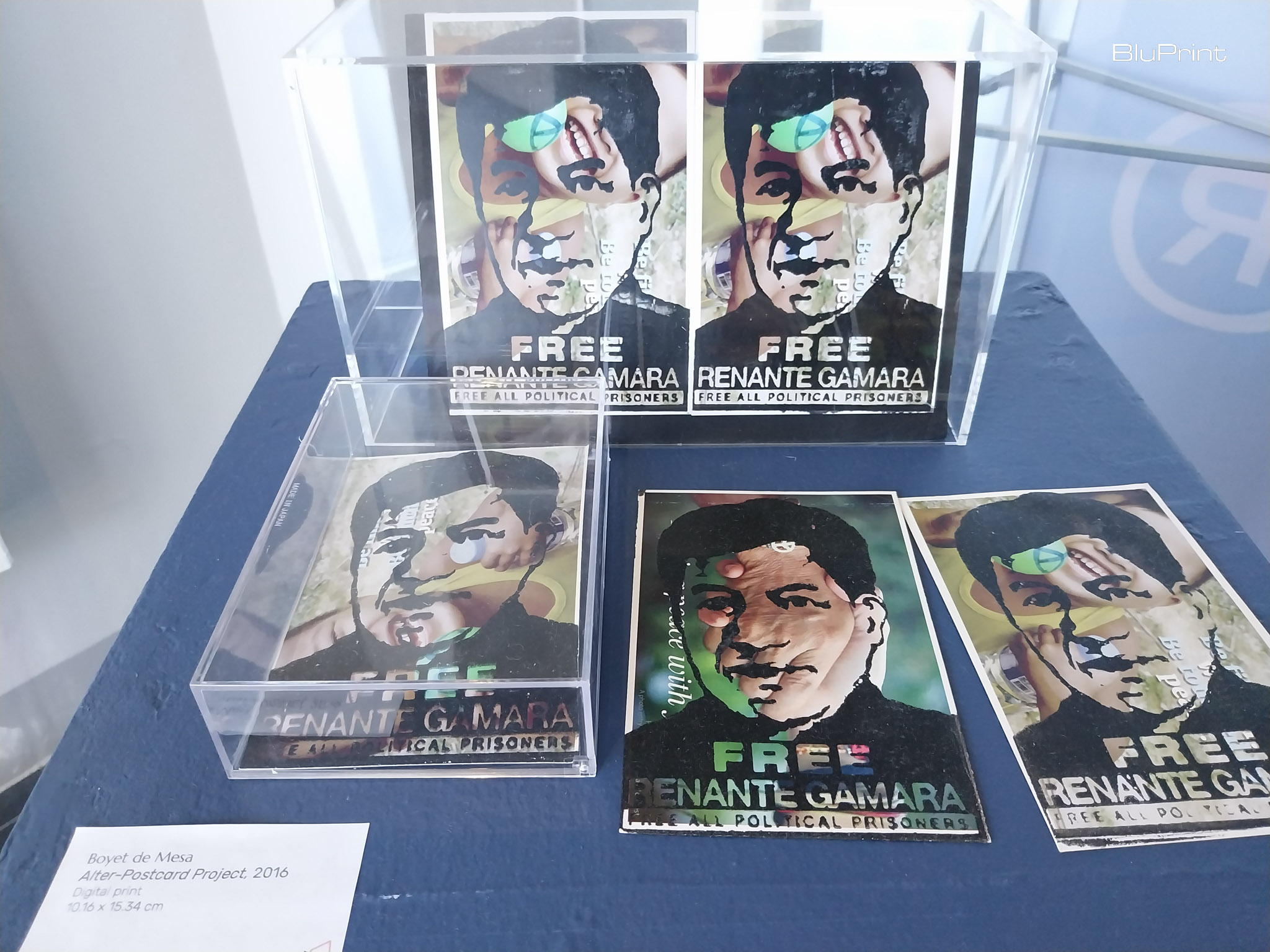

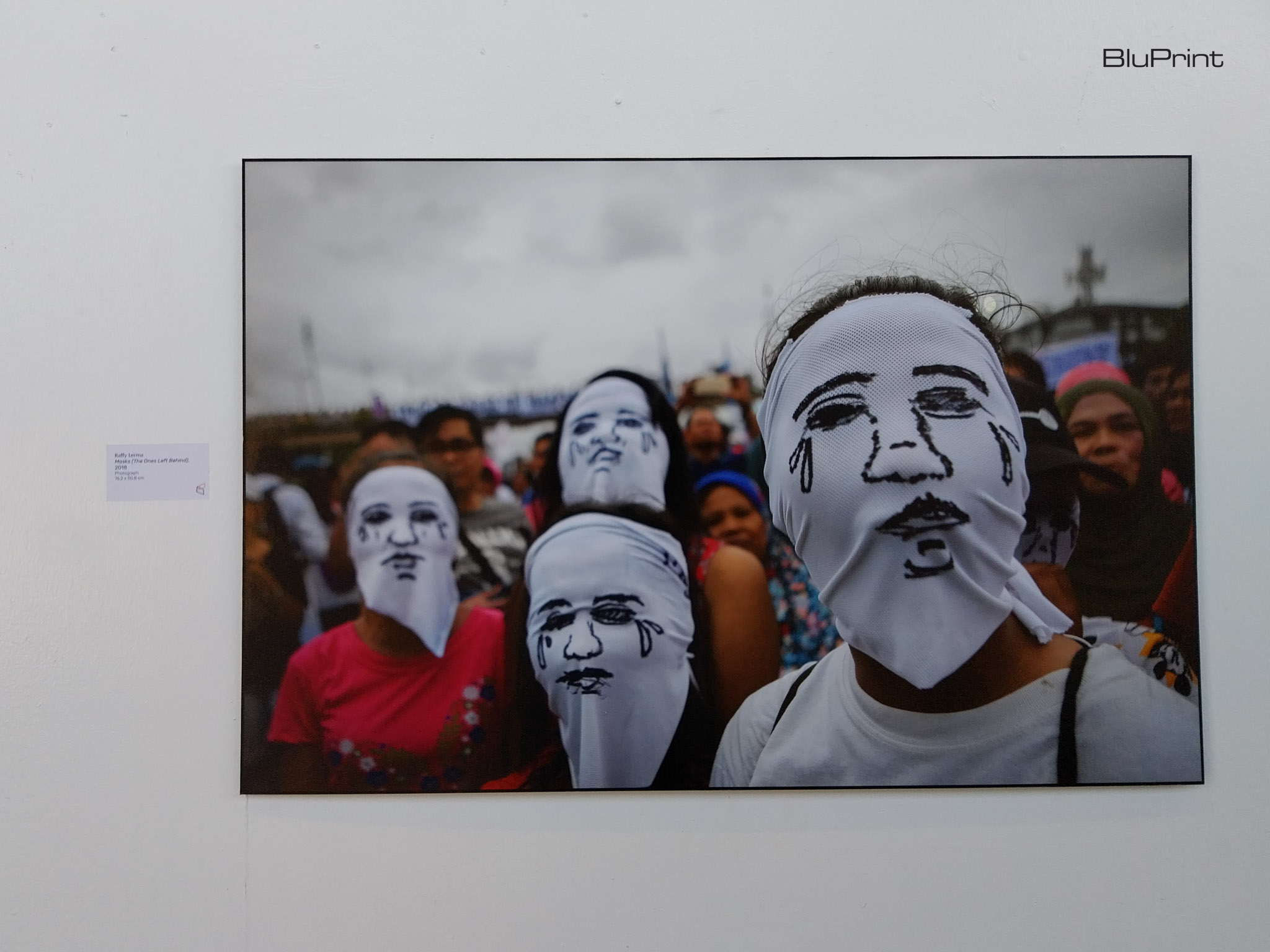

It highlights the continued struggle of human rights during Duterte’s War on Drugs onwards, and the artistic documentation of the era’s struggle against the violence. It features works from photojournalist Raffy Lerma, as well as artists like Tarantadong Kalbo, BenCab, and Boyet de Mesa.

Curator Lisa Ito wrote that she hopes that the exhibit will “activate a vital link between visual practices which produced ‘objects of demonstration’ and ‘disobedient objects.’”

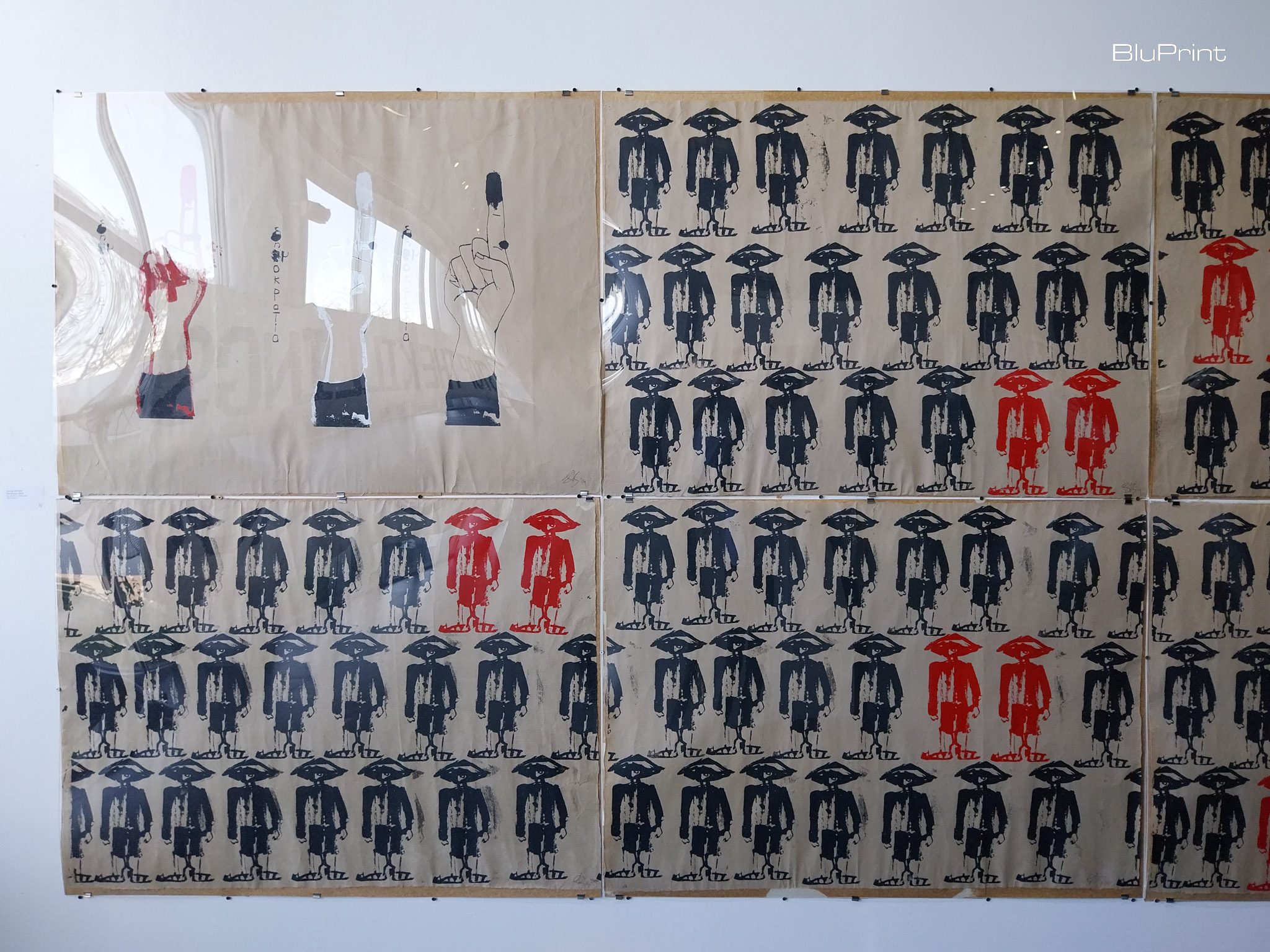

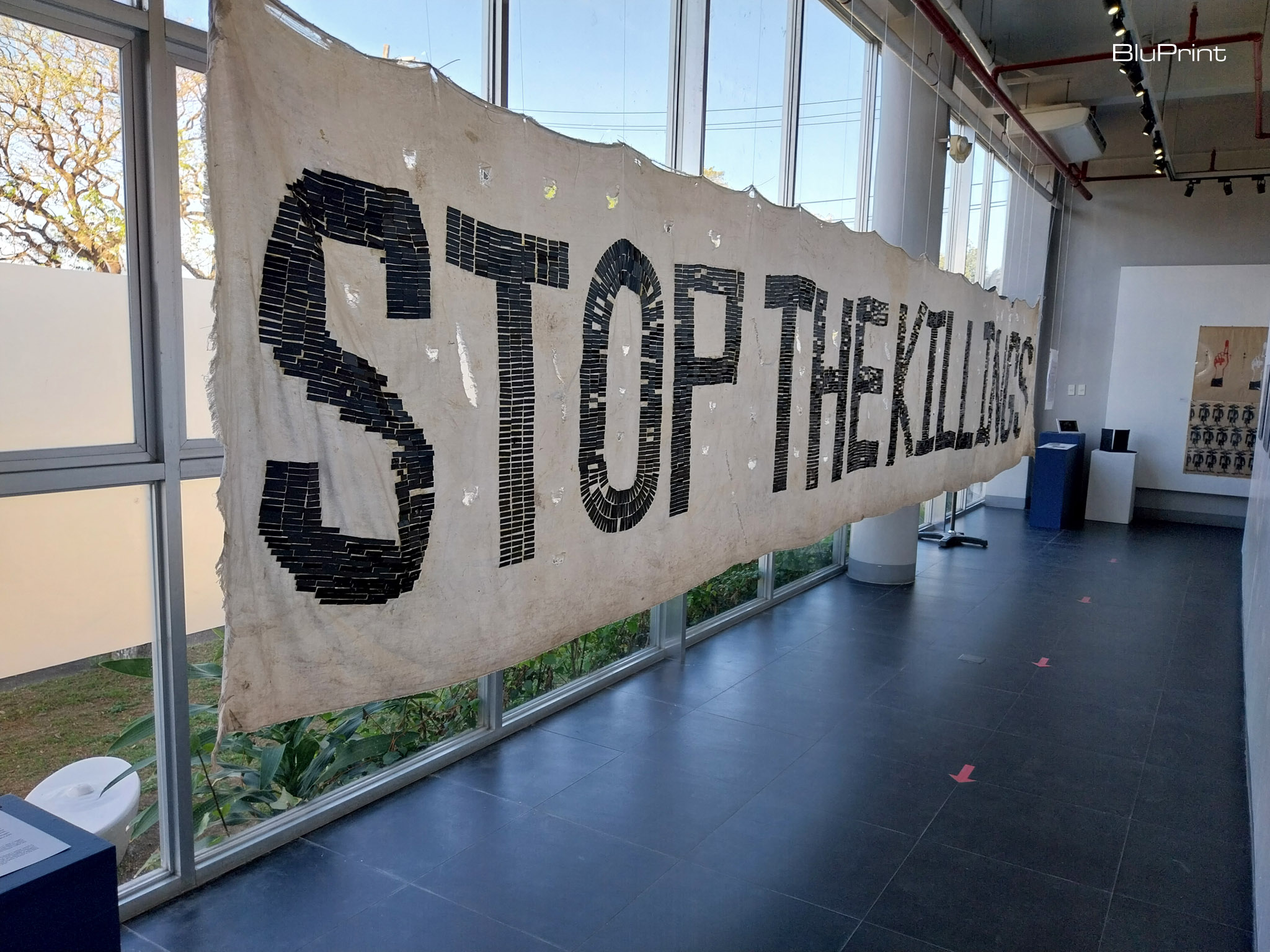

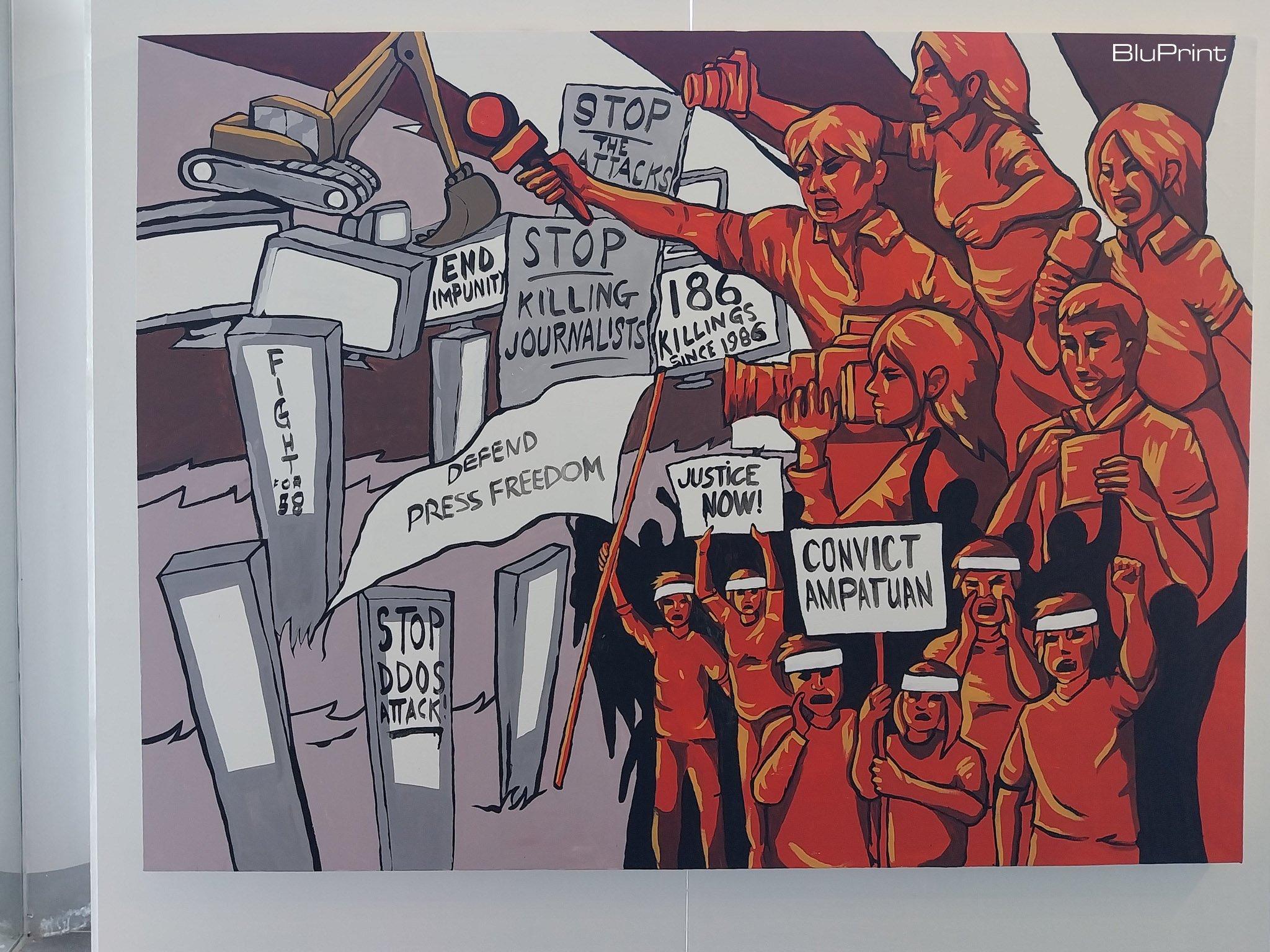

Protest is Art

Many of the works there are of a multimedia sort, from a giant “Stop the Killings” banner made of mourning pins from Respond and Break the Silence Against the Killings (RESBAK) to a recreation of the Fight for 58 mural made for the anniversary of the Ampatuan massacre originally confiscated by the police.

It shows the variety of different ways that protest art can exist, within the canvas and outside of it. Photographs become fighting symbols for dissent; a piece of bamboo furniture becomes a figure of the empathy and survivalist instinct of the typical Filipino.

To round up the month-long exhibit, CAP arranged closing talks from two contributors of the exhibit: the aforementioned Lerma, as well as Patreng Non, who helped kickstart the Community Pantry movement during the pandemic.

The Consequences of Fighting Power

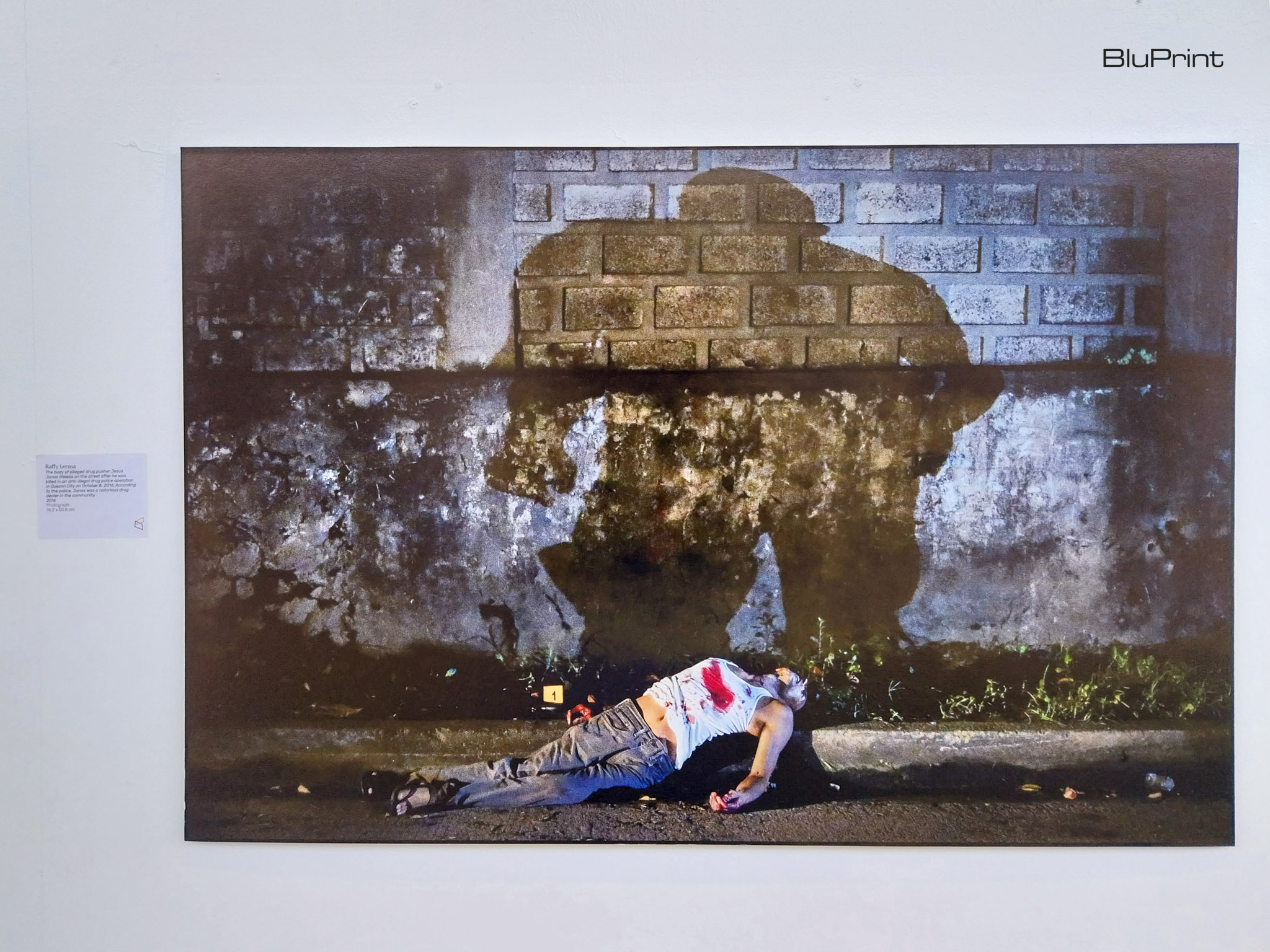

Raffy Lerma worked as a photojournalist for the Philippine Daily Inquirer when Duterte became President. He said he consciously decided to work the night shift in the newspaper as a way of documenting the potential effects of Duterte’s statements against drug addicts in the country.

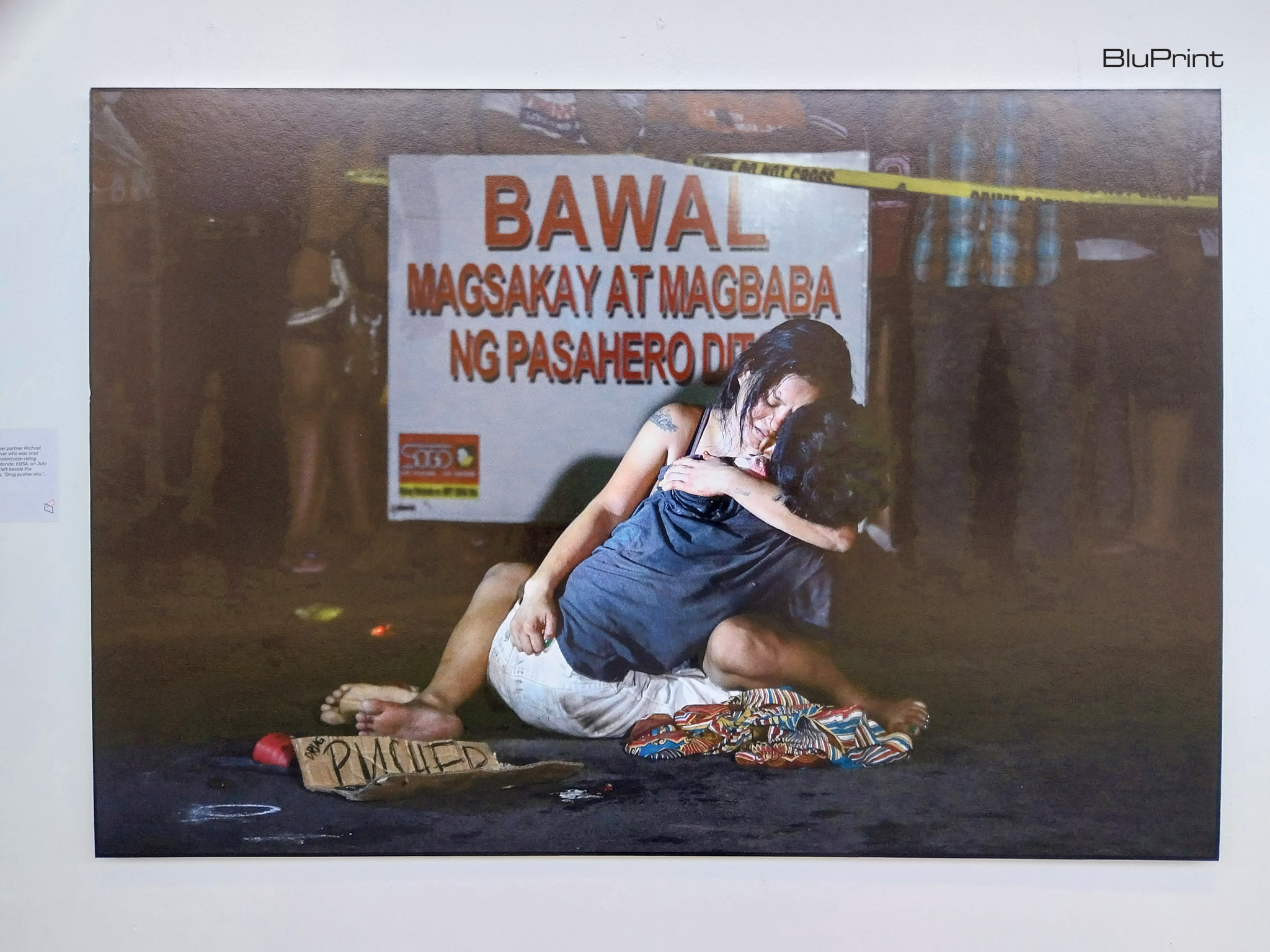

During this time, Lerma famously shot the photograph of Michael Siaron being cradled by his partner Jennilyn Olayres after he was shot to death by a riding-in-tandem group. Nicknamed Pieta by the public due to its resemblance to the Michelangelo sculpture, Lerma said that the evocative photo made him a target of hate and misinformation, with many claiming that the photograph was staged.

To Keep Fighting Even in the Face of Abuses

Patreng Non found a similar amount of resistance when she debuted the Community Pantry in April 2021. It was a different stage of the pandemic when stores were starting to open up, but many people were still unable to get the supplies they needed for their day-to-day lives.

Non saw that desperation and decided to open a pantry where people could take the supplies they needed, and leave some for people in return. “Tayo tayo na lang eh. Ito, ang sikmura natin ang importante,” she said about it. (It’s just us then. Our hunger becomes the only important thing.)

Because of this one act, she became the target of red tagging by prominent figures in the government, baselessly accusing her of being a member of the NPA. She said that one of her accusers, Lorraine Baduy, claimed that she was a rebel due to her membership to the UP Mountaineers, an organization that Baduy was also previously a part of.

Non has been cyber-bullied, harassed, and at some point in time a victim of an attempted break-in. Lerma, meanwhile, had to defend the integrity of his work online. Both continually have to battle the onslaught of trolls and pro-Duterte people, which had adverse effects on their mental health.

Fighting for the Victims of the Drug War

Lerma and Non believe in the power of art to illuminate the darkness of society, especially in helping the needs of the people. Lerma, especially, was changed by the government’s response to the War of Drugs.

His experience of documenting the start of the Drug War was harrowing, documenting a large amount of dead. Lerma said that in the deadliest week of the Drug War, over 80 people were killed in three days, including 32 people in one night. Despite the increasing death count, however, Duterte continued goading the people on.

“The words of our leaders matter. Whatever he says….sabi niya joke lang iyon?” Lerma said. (He said it was just a joke?)

His experience with the War on Drugs pushed him towards leaving his post in the Inquirer and work freelance to document the effects of Duterte’s war full-time. He continues to advocate for the victims today, and his photographs are being used by the families to push for autopsies to find out how they really died.

“Photographs are not just photographs alone, they are evidence and ways to get justice.”

Art Can Change Society

Art is a necessary component of dissent. It opens up our perspective into different things, and provides itself as a necessary weight against state impunity. Art can give a voice to the silenced, and allow them to continue pursuing justice in an unjust world.

Warm Bodies shows this fight, and its importance even as it affects the artists who advocate for it. In a world continually imperiled by the powerful pushing down dissent, artists become an important factor in the continued fight against institutional crimes and abuses.

Related reading: Daring By Design: Stories of courage and creative pursuits