When one thinks of the Tree of Life, several images may come to mind because of its deep roots in different cultures and religions. The first and last books of the Bible mention it together with the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden, while the Bodhi Tree in Buddhism was where Siddhartha Gautama […]

‘Stakeholding’: Looking at the Praxis of Political Ideology in Gaming

For If Art is a Hammer 2025, the Concerned Artists of the Philippines diverged into a different form of artistry not typically discussed in mainstream circles: games, specifically board games. For their final talk, they invited artist Lyra Garcellano to discuss her board game Stakeholding, and why gaming is an inherently political artwork despite what online discourse would say.

The Inherent Permission Politics of Gaming

Lyra Garcellano approaches gaming by seeing it as the inherently political vehicle that it is. She cites different games that she grew up with—Old Maid, Monopoly, Small World, Trading Game: France—Colonies—as examples of how games as an artform pushes a conservative agenda upon the world today.

Games like Monopoly, originally created as an anti-capitalist game that shows the folly of the system and the benefits of spreading wealth to others, becomes a rabid push of accumulation of resources that seeks to justify the capitalist mindset happening in our society today. Small World and Trading Game, she argues, justify colonization and territory expansion through a fun, zany atmosphere.

While attempting to seem neutral, they all push a conservative political agenda that seeks to maintain the status quo of the time.

Creating Games Rooted in Togetherness

Garcellano sees games of all sorts as a way of capital to create a permission structure around the ideas it wants to push, from the patriarchy to colonization to the different social statuses and how we interact with others through it. It trains us, she said, to see the world in that specific light and to engage with it with no alternatives in sight.

“[It gives us] the propulsion, it motivates us on how we strategize…and negotiate our daily existence,” she said.

In response to that, Garcellano posed a question to the audience related to how we create games: “What if you decide to make life-generating art and not value-losing genocide?”

She desired to create a game that returns to the roots of why we create art in the first place, one that acknowledges the world we live in without justifying the status quo that exists. “It’s really about forming cultures and forming communities with each other and trying to socialize in a way that we actually learn from each other.”

A Board Game Rooted in Inequality

Garcellano introduced the audience to her game, Stakeholding Chapter 1. A four- to six-player tabletop game, Stakeholding lets the players design the game board and create their own player’s template.

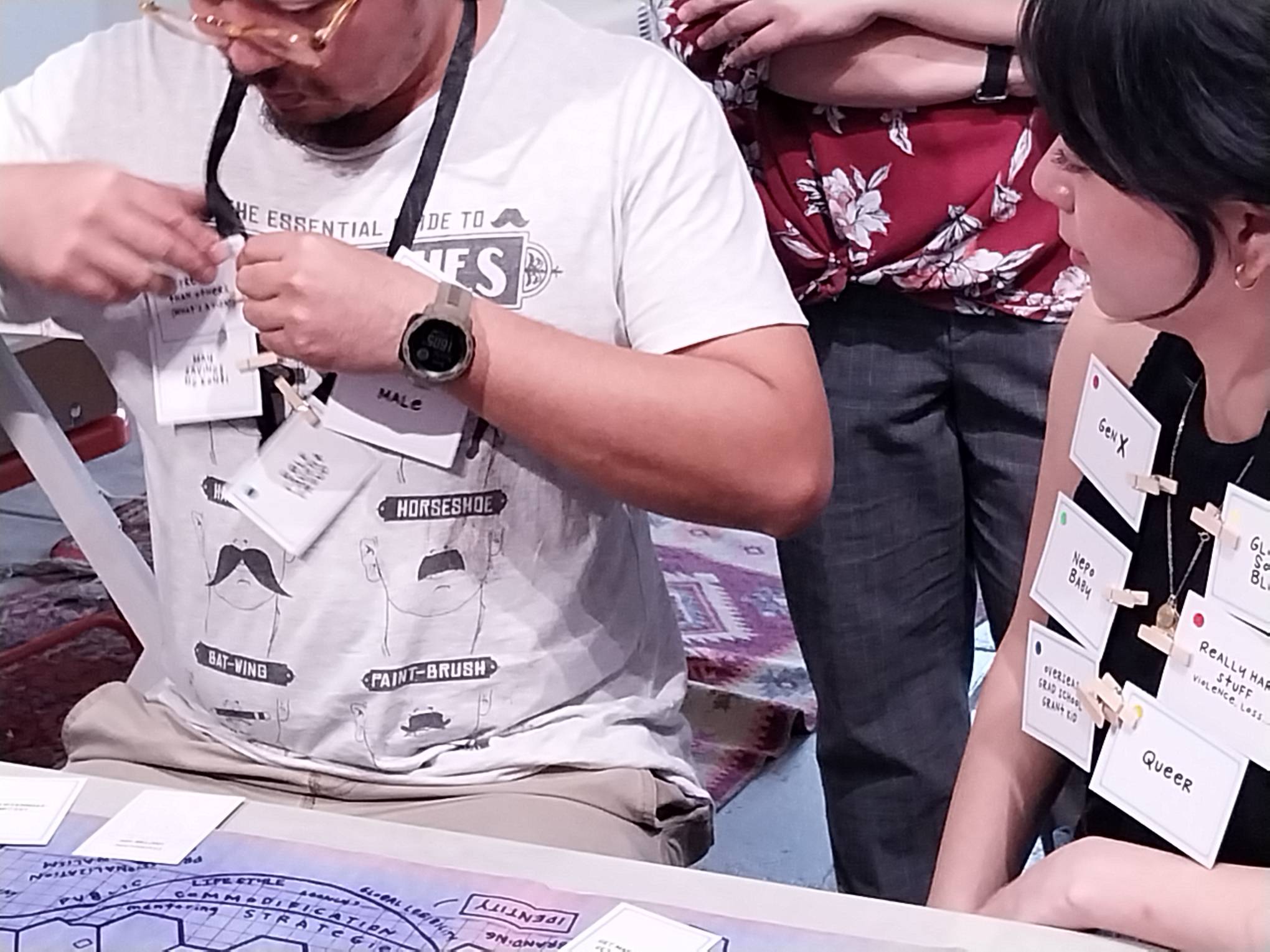

For the rest of her time during the talk, she found six volunteers in the audience to demonstrate the gameplay of Stakeholding. The game can typically take hours to play, so she provided a truncated version that lasted around forty minutes, with her explaining the rules and the pieces of the game to both the players and those watching.

There’s a hexagonal playing field, with different zones that players can place wherever they want. Then, one picks from a random bag of different personalities to see how much “capital” they have. She modelled it after our current perceptions of what makes a person today: gender/sexuality (men get two coins, women and queer people get one, and those who prefer not to say get zero), birthplace/passport strength, and even one’s past trauma.

The players also get to pick out two goals for their character: one that is revealed to everyone, and another that is kept secret until the end. From there, each character accumulates points based on how they respond to the challenges of every scenario.

‘Stakeholding’ as a Reflection of Reality

It’s a very dynamic game to watch and play because it centers around the complicated interactions we have between the environment we live in and the privileges that each character has.

Different playing cards introduce scenarios that add or remove privileges at random, and some of these scenarios force players to work together to help attain some of their goals. Beyond that, the construction of the zones in the playing field will likely cause headaches to the gamers as they attempt to navigate these zones for their benefit.

(Early in the game, Garcellano made a joke about Stakeholding being a good game to flirt with people because of the social aspect of it, how it allows players to draw from their own personal knowledge and experiences to add extra dimensions to their characters. Having seen the gameplay, this writer is inclined to agree with that assessment.)

Stakeholding really captures the randomness of life and how the struggles we face are mostly out of our control—sometimes people are really just born in a more privileged place that allows them to attain their goals faster than others. Even the game’s mechanics acknowledge that: the game sometimes ends in a “wild card” that disregards the points entirely to pick a winner at random.

That’s the appeal of the game: its refreshing openness to the unfairness of the world, and how it allows players to poke fun at this dynamic while ruminating on why we created such a system for our world today.

No Praxis in Community?

As part of the program, game developer and writer Nissie Arcega came in to respond to the presentation of the game. She facilitated a discussion about the essential nature of politics in gaming, and how that can become a vehicle towards disseminating progressive ideas into the community.

Arcega linked Stakeholding to the broader paradigm of gaming communities as a whole. She points out that games today, in whatever medium, are seen as escapism from the world. Many gamers are just looking for people to hang out with to enjoy their time together.

So what does it mean that the culture around a lot of games tend to be toxic? She cites how Minecraft, for example, encourages fascist networks within their players, or the general toxicity of different competitive games. And even popular wholesome, cozy games tend to wash away responsibility for the world we have today.

“These companies, they don’t care to regulate the communities that they build from the product that they’ve made because they think it’s not their responsibility,” she said.

“We always think that we escape through games. I can also include the wholesome, cozy game trends now,” she continued later. “That’s the complete opposite of what the male-centric games are, supposedly. But it’s also a form of escaping all sorts of reality. So they don’t like it, they don’t like any form of struggle which also, in a way, [reinforces] a racist reality—our social reality.”

Mirror to the Self

Using that framing, Arcega discussed the emotions and playing experiences that bubbled up during Stakeholding. She acknowledged that many people were uncomfortable in how the game integrates our material reality into its mechanics, but that for others it made the game fun and engaging.

Many found the game illuminating in the way it held a mirror not just to the values that each player has, but to the values of our society as a whole. Some players said that they could see players from different backgrounds having different takeaways from the experience. In the group that attended the talk, they saw it as a refreshing direction, and offered suggestions on how to make it more realistic and tethered to our social milieu.

And from there, Arcega posited the question to the people who attended the talk: what does it mean to win? How do you create a game that brings a community together rather than letting the players fight? What does it take to win in a society where toxicity and passivity are encouraged, where the system works to reinforce itself through our art?

How do you win for yourself?

These questions are, of course, left largely unanswered; it’s a personal thing that varies from person to person. But Stakeholding as a game advocates for a society that’s built around personal reflection like that, and shines forward a potential world where games of any medium don’t just reinforce the status quo but work towards building a better, collectivist future together.

Photos by Elle Yap.

Related reading: How Inclusive Design Promotes Community and Social Integration