As it nears its landmark 50th anniversary, the Philippine International Convention Center (PICC) firmly secures its place as an architectural titan. A designated National Cultural Treasure (NCT) designed by National Artist Leandro V. Locsin and completed in 1976, this Brutalist icon recently experienced a monumental act of stewardship: a surgically precise overhaul executed in a […]

Brutalist Architecture in the Philippines: A Comprehensive Analysis

The emergence of brutalist architecture in the Philippines during the mid to late 20th century marked the country’s engagement with international architectural movements. Architects in the Philippines, exposed to international publications and architectural discourse, would have been aware of and influenced by the rise of brutalism in Europe and other parts of the world. However, the adoption of this international style in the Philippine context was not a simple replication.

Instead, local architects critically engaged with its principles, adapting them to the specific environmental and cultural nuances of the archipelago. The unique characteristics of Philippine brutalism reflect a synthesis of international architectural ideas and local realities. They hint at modifications made to suit the tropical environment and incorporate elements of the local cultural context. Understanding this initial adaptation is crucial for appreciating the distinctive evolution of brutalism within the Philippines.

Defining Brutalism

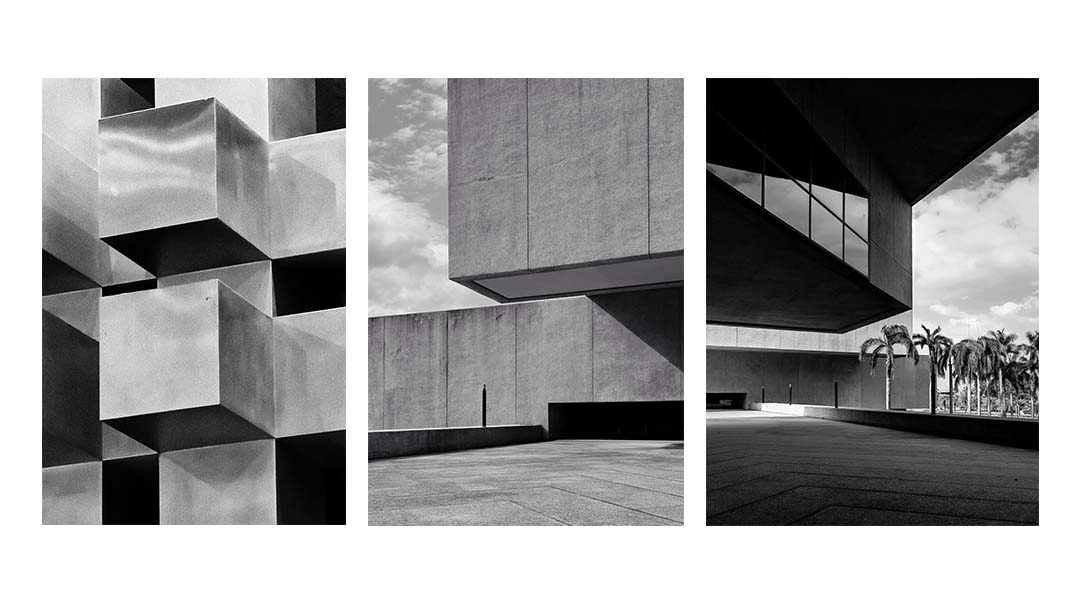

Brutalism flourished from the 1950s to the 1970s, characterized by stark, monumental forms and the unapologetic use of raw materials, most notably béton brut, or raw concrete. The term itself originated from the French phrase popularized by Swiss architect Le Corbusier. It speaks to the style’s emphasis on the inherent qualities of construction materials, left exposed rather than concealed or embellished.

Core characteristics of brutalist architecture include a deliberate display of structural elements. These often feature repetitive modular units that create a sense of scale and mass. This architectural approach often reflects an ethical stance. It prioritizes honesty in materials and a functional expression of the building’s purpose over purely aesthetic concerns.

The emphasis on raw materials and exposed structure depart from the ornamentation prevalent in earlier architectural styles. Brutalism signalled a shift towards a more direct and utilitarian approach to design. This focus on fundamental building blocks suggests a desire for authenticity and a celebration of the inherent textures and forms of construction materials.

Brutalism in the Philippines: Context and Influences

The period following World War II presented the Philippines with the immense task of reconstruction and modernization. The devastation caused by the war necessitated widespread rebuilding of infrastructure and the creation of new civic and residential structures. In this context, brutalism, with its emphasis on efficiency, monumentality, and the readily available material of concrete, may have been perceived as a fitting architectural language to express national progress and strength in the post-war era.

The desire to project an image of a modern and forward-looking nation likely contributed to the adoption of architectural styles seen as contemporary and technologically advanced. Concrete was already becoming a symbol of modern construction capabilities. This focus on rebuilding and establishing a new national identity likely made the bold and modern aesthetic of brutalism appealing.

Beyond the immediate post-war needs, the global rise of brutalism in the mid-20th century significantly influenced architects in the Philippines. This period saw prominent international figures championing the style, with their seminal works serving as inspiration and models for architects worldwide. The Philippines, like many other nations, was part of this global architectural discourse, with local architects seeking to align themselves with international developments and innovations in design.

The adoption of brutalism in the Philippines should therefore be understood as part of a broader global phenomenon. It reflects the interconnectedness of architectural ideas and the desire of local practitioners to engage with contemporary architectural movements. Architectural knowledge and styles often disseminate across national borders through various channels, including publications, educational institutions, and the movement of architects themselves. All this likely contributed to the spread and adaptation of architectural trends like brutalism.

The Indelible Mark of Leandro V. Locsin

Among the key figures who shaped the architectural landscape of the Philippines during the latter half of the 20th century, National Artist Leandro V. Locsin stands out as a dominant force in the realm of brutalist architecture. His architectural philosophy, characterized by a profound understanding of form and space, found powerful expression through the use of monumental forms and the tactile quality of concrete.

Locsin’s signature style often involved the creation of seemingly floating volumes and the interplay of massive geometric elements. And his work left an indelible mark on the Philippine built environment. Iconic examples of his brutalist works include the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) (1969) and the Philippine International Convention Center (PICC) (1976), both located in Manila. These structures, with their imposing concrete masses and powerful presence, exemplify the core tenets of brutalist design as interpreted by Locsin.

His other notable Brutalist works, such as the National Arts Center (1976) in Mt. Makiling and the Development Academy of the Philippines (DAP) (1977) in Tagaytay, demonstrate a thoughtful integration of monumental concrete forms with the natural landscape.

Prominent commissions for significant national buildings suggest that brutalism was not merely an aesthetic preference. It was also a style favored for representing national identity and hosting important cultural and political events. The monumentality and imposing presence of Locsin’s brutalist creations conveyed a sense of power and permanence, aligning with the aspirations of a developing nation.

Zaragoza, Formoso, Ramos, and Luz

While Locsin may be the most celebrated proponent of Philippine Brutalism, a cadre of visionary architects contributed to this architectural era, shaping the nation’s civic, commercial, and residential spaces.

The Brutalist landscape of the Philippines is far richer than the work of a single architect. In Pasig City’s business district, the Meralco Building (1969), designed by Jose Maria Zaragoza, yet another National Artist for Architecture, stands as an early and prominent example of Brutalist principles applied to a commercial structure, with its strong vertical lines and textured concrete facade. Zaragoza also designed the unique Commercial Bank and Trust Company Building (1969) in Escolta, Manila, a semi-dome structure recognized as an Important Cultural Property.

Other key figures include Gabriel Formoso, the architect behind The Peninsula Manila (1976), a landmark hotel in Makati that originally featured a grand Brutalist fountain. The GSIS Building (1986) in Pasay, designed by Jorge Y. Ramos and Associates, draws inspiration from the Banaue Rice Terraces, translating the ancient agricultural marvel into a modern concrete form that currently houses the Philippine Senate.

The Ramon Magsaysay Center (1967) in Malate, Manila, a work by Alfredo J. Luz and Associates with consultants Pietro Belluschi and Alfred Yee Associates, is another significant example of the era’s architectural prowess. Further afield, the Pasig Revolving Tower (1974), designed by Architect Edward Medina, stands as a rare Asian example of a Brutalist tower with a revolving restaurant.

Brutalism and the Marcos Regime

The presidency of Ferdinand Marcos (1965-1986) was a period of significant political and cultural developments in the Philippines. During this time, brutalist architecture, with its monumental scale and imposing presence, appeared to align with the regime’s image of power, progress, and national ambition. The visual weight and grandeur of brutalist structures could have been seen as an architectural manifestation of the government’s authority and its aspirations for national development. This potential alignment between the aesthetic of the regime and the visual language of its public buildings suggests a deliberate choice to project an image of strength and modernity.

The concentration of such large-scale brutalist projects during this period indicates a significant investment in public infrastructure and cultural institutions, reflecting the priorities of the Marcos administration. The selection of brutalism for these important national buildings implies a conscious decision to associate this architectural style with the image and aspirations of the nation, serving as prominent landmarks that shaped the urban landscape.

However, brutalist architecture is not without its critics. Some perceive its starkness and emphasis on raw concrete as cold, impersonal, or even authoritarian. In the context of the Marcos regime, these criticisms might be interpreted in different ways. While some might view the monumental scale and imposing nature of these buildings as symbols of national pride and progress, others could see them as reflections of the authoritarian tendencies of the government.

The visual characteristics of brutalism – its scale, its use of raw concrete, its often imposing forms – can evoke different emotional responses and interpretations depending on one’s perspective and historical context. The legacy of this architectural style in the Philippines inevitably intertwines with the complex and often debated history of the Marcos era.

Tropical Brutalism

Characterized by a tropical climate, the Philippine archipelago presents unique challenges for building design and material choices. High temperatures, persistent humidity, heavy rainfall, and intense sunlight are significant factors that architects must consider to ensure the comfort, durability, and longevity of their structures. These climatic conditions impact everything from thermal performance and ventilation to material degradation and maintenance requirements. The harshness of the tropical climate necessitates careful consideration of material properties and building orientation to mitigate the negative effects of heat and humidity.

In response to these challenges, architects in the Philippines who embraced brutalist principles often employed specific design strategies to adapt the style to the local climate. One common approach involved the use of deep-set windows and various sun-shading devices, such as louvers and overhangs, to minimize the amount of direct sunlight entering the interior spaces, thereby reducing solar heat gain.

The incorporation of natural ventilation was another crucial adaptation, with architects strategically placing openings and designing airflow pathways to promote cross-ventilation and help regulate indoor temperatures and humidity levels. Furthermore, some architects explored the use of locally sourced materials or experimented with modifications to concrete mixes to enhance their durability in the humid tropical conditions.

Adapting Form and Materiality to the Philippine Climate

Integrating courtyards and green spaces within or around brutalist structures also served as a way to provide shade, improve the local microclimate, and create more comfortable and livable environments. These adaptations demonstrate a thoughtful engagement with the local context, moving beyond a purely stylistic application of international brutalist trends.

Concrete, brutalism’s quintessential material, presents both advantages and challenges in a tropical climate. Its inherent thermal mass helps moderate indoor temperatures by absorbing and slowly releasing heat. However, its susceptibility to moisture absorption also leads to issues like mold growth and structural damage if not properly addressed.

It’s important to consider these factors when selecting and detailing concrete and employ specific techniques or treatments to enhance its performance and durability in the face of constant exposure to the elements. The long-term performance and weathering of concrete in the tropical climate can also contribute to the unique aesthetic character of these buildings over time, as the material interacts with the environment.

The Imperative of Preservation

The preservation of brutalist architecture in the Philippines faces a multitude of challenges. One significant hurdle is negative public perception, which stems from the style’s perceived austerity or its association with a specific political era. This lack of widespread appreciation can make it difficult to garner support for preservation efforts.

Furthermore, the inherent maintenance requirements of concrete structures in a tropical climate can be costly and complex. The rapid pace of development in many urban areas of the Philippines also poses a threat, with brutalist buildings seen as outdated or underutilized, leading to pressure for their demolition to make way for new construction. Additionally, there may be a general lack of awareness or understanding regarding the historical and architectural significance of these buildings, further hindering preservation initiatives.

Despite these challenges, there are ongoing efforts and initiatives aimed at preserving brutalist architecture in the Philippines. Architectural organizations and heritage conservation groups are increasingly recognizing the historical and cultural value of these structures and are undertaking documentation and research projects to raise awareness. Most recent are the rehabilitations of the CCP and PICC.

Advocacy efforts are also underway to promote the appreciation and protection of significant examples of Philippine brutalism. In some cases, architects and developers explore adaptive reuse, which involves repurposing existing brutalist structures for new functions while respecting their original architectural integrity.

There is also a growing movement to identify and potentially list significant brutalist buildings as heritage sites, which could provide them with a greater level of protection under national and local laws. Successful preservation often requires collaboration among architects, historians, government agencies, and the public to ensure the long-term survival of these buildings.

The Modern Revival

Decades after its mid-century heyday, Brutalism is experiencing a quiet renaissance in the Philippines. Contemporary architects are re-examining the style’s core principles, drawn to its material honesty, sculptural potential, and inherent strength. This renewed interest, often termed “Neo-Brutalism,” is not merely a nostalgic revival but a modern reinterpretation, adapting the aesthetic for a new generation while continuing the tradition of “Tropical Brutalism.”

This resurgence is particularly evident in private residences, where architects are exploring raw concrete’s capacity to create powerful, minimalist, and livable spaces that harmonize with the country’s lush environment.

In a departure from the monolithic and heavy fortresses often associated with historical Brutalism, a new wave of Filipino architects is redefining the style’s boundaries. They retain the style’s honest use of raw concrete but integrate a generous amount of glass and steel, creating dramatic cantilevered volumes that feel both massive and surprisingly light.

A Neo-Brutalist Resurgence

This contemporary approach challenges the very definition of a Brutalist building. Where traditional Brutalism often emphasized solid, impenetrable masses, these architects craft structures that are porous and interactive. For instance, Jagnus Design Studio, guided by a philosophy of “form follows feeling,” utilizes raw concrete not to enclose, but to frame spaces that “breathe.” Their designs often feature imposing concrete shells punctuated by vast glass walls and openings, dissolving the barrier between the robust structure and the surrounding environment. This creates a dynamic interplay between groundedness and openness, a signature of this modern movement.

Similarly, LLG Architects’ “Hillside Revival” project showcases this subversion. The residence balances raw, unfinished concrete surfaces—a clear nod to Brutalist materiality—with expansive glazing and warm wood accents. The result is a home that feels both raw and refined, protective and welcoming, demonstrating a clear evolution from the austere monuments of the past.

The work of Jim Caumeron, such as his ‘Through House‘, masterfully plays with this concept of porosity. He uses solid concrete walls to direct views and create privacy, but then perforates the structure with strategic voids and floor-to-ceiling glass, allowing light, air, and nature to permeate the living spaces. The effect is less of a single, heavy object and more of a curated collection of volumes and openings.

Another prime example is Casa Borbon in Batangas, designed by Amon Cali of Cali Architects. Explicitly described as a neo-brutalist structure, the house is conceived as a habitable sculpture. Its strong, geometric lines, extensive use of raw concrete, and large overhangs are direct descendants of the Brutalist ethos.

This reinterpretation is also beautifully captured in the Parallel in Tanauan, Batangas. The property consists of two massive, board-formed concrete villas running parallel to each other. While the materiality is unapologetically Brutalist, its function is one of openness. The parallel forms act as a colossal frame, curating breathtaking views of the surrounding landscape and Taal Lake. Instead of an imposing fortress, the raw concrete creates a serene, private sanctuary where the structure’s strength is softened by the lush greenery it embraces, perfectly illustrating the dialogue between mass, nature, and human-centric design that defines this contemporary movement.

These modern examples demonstrate that the spirit of Philippine Brutalism is not confined to the monumental structures of the past. By embracing raw concrete and bold forms, contemporary architects are forging a new path, proving the style’s enduring relevance and its unique suitability for the archipelago’s landscape and climate.

Philippine Brutalism’s Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Love it or hate it, Brutalist architecture in the Philippines represents a significant and provocative chapter in the nation’s architectural story. The original movement’s principles of structural honesty and material expression left a lasting impact, fostering a deeper appreciation for functional, unornamented design.

While the dominance of the monolithic “fortress” has waned, the core tenets of Brutalism are experiencing a dynamic resurgence. The heavy, imposing forms of the past are giving way to structures that, while still celebrating raw concrete, are also porous, light, and deeply connected to their tropical environment.

This evolution marks a shift in focus from the monumental to the human. In a multitude of contemporary residences, raw concrete frames intimate spaces and curates views, dissolving the barrier between indoors and out. It retains the material honesty and strength of its predecessor but embraces a newfound sense of openness and warmth.

Looking ahead, these Brutalist principles, both old and new, hold profound relevance. The focus on durable, long-lasting materials like concrete speaks directly to modern concerns of sustainability and resilience, reducing the need for frequent replacement. Furthermore, the style’s adaptability—from the civic grandeur of its first wave to the human-centric focus of its current form—offers invaluable lessons.

As the Philippines continues to navigate the complexities of climate change and rapid urbanization, the enduring and evolving legacy of its Brutalist heritage provides a powerful and insightful guide for shaping the built environment of tomorrow.

Read more: Brutalism: This Architectural Prodigy Is Far From Gone