Breaking through in their respective careers is a daunting task for any young professional. For Architect Pierre Briones, architecture has always been an intentional pursuit. Having spent much of his childhood around construction sites, Briones’s environment shaped his interest in architecture, including his fascination with how structures and buildings are built. “Choosing architecture was never […]

Famous Architecture in the Philippines: 7 Iconic Buildings and Their Historical Significance

Architecture is a reflection of a nation’s social milieu upon its construction. It is a physical manifestation of existing power structures, political and social environments, and cultural values. In the Philippines, architecture is a display of how Filipinos interact with the natural environment.

From Philippine vernacular architecture to colonial structures, architecture has played a significant role throughout the country’s spatial history. The Philippines boasts numerous iconic architectural structures, each with its own rich history. We’ve compiled a selection of these significant buildings, highlighting their historical importance.

Humble Origins: The Bahay Kubo

The bahay kubo is the fountainhead of many of the most iconic buildings in the Philippines. It is a typical one-room, cubic house raised on stilts, primarily constructed out of bamboo, thatched dried palm leaves, and grass. The design follows similar themes: a square or rectangular structure made of bamboo, a steep thatched roof, and a wooden post that raises the house above ground.

The bahay kubo was the precursor to the bahay na bato, which emerged during the Spanish colonial period. While the Spanish replaced the primary materials with stone, the structure followed that of the bahay kubo. The skeletal structure remained as a house on stilts, with an open layout for proper ventilation in a tropical climate.

In the wake of the Japanese occupation, the recently independent Philippines longed to build a distinct national identity. The reconstruction of Manila after World War II provided Filipinos with the opportunity to define Philippine architecture. Indigenous and cultural traditions were looked at as sources of inspiration in creating a national identity.

The bahay kubo was considered the embodiment of authentic Philippine architecture. 20th-century architects viewed it as a model for their works, considering it part of the Philippines’ architectural heritage. It influenced the works of significant architects, such as Leandro Locsin and Francisco Mañosa.

Many architectural works in the country consist of a direct quotation of the bahay kubo, primarily to express an understanding of the traditional. Many of the listed notable architectural works below have taken inspiration from the bahay kubo in the quest to establish the domains of Filipino architecture.

The Ruins

The Lacson Ruins was built in the early 1900s as a tribute to Don Mariano “Anoy” Ledesma Lacson’s late wife, Maria Braga, who passed away during the childbirth of their eleventh child. Located in Talisay, Negros Occidental, it was the grandest residence in the region at the time. Simply referred to as The Ruins, the mansion has become a tourist attraction.

This ancestral mansion stands on a 440-hectare sugar plantation. The mansion utilized A-grade concrete and steel bars. The construction process was managed by Felipie, one of the sons, to ensure the proper implementation of the materials.

Designed in the neo-Romanesque style, the mansion consisted of key elements such as rounded arches of the entryways and vast decorative details. The exterior has an almost smooth, marble-like structure, with shelf motifs placed on top as a possible reference to Maria Braga’s sea-faring father. The mansion was also inspired by the residences of New England ship captains, which influenced the crown-life roof of the mansion.

The mansion was destroyed during World War II. Under the advice of the guerrilla forces, Don Anoy set the mansion on fire himself. After three consecutive days and numerous drums of gasoline and oil, the mansion was reduced to its steel and concrete shell. The family decided not to rebuild the mansion; instead, they left behind the magnificent, unscathed façade that leaves behind a legacy of love and wealth.

Manila Metropolitan Theater

The Philippines in the early 20th century witnessed a shift in colonial power—from Spain to the United States of America. This shift symbolized a new social order while introducing the country to new architectural styles. The Americans established structures, such as schools and city halls, usually in the Beaux-Arts vocabulary during the initial decades of their occupation. These structures represented their colonial presence and supposed cultural superiority.

The government commissioned architect Juan Arellano to create blueprints for the Manila Metropolitan Theater (MET). He was sent to the United States to study under the guardianship of Thomas W. Lamb of Shreve and Lamb, a consulting architect for the project. The MET was Arellano’s first deviation from his inclination to the Beaux Arts into Art Deco.

Completed in 1931, the MET was the largest theater to be constructed at its inauguration. Its role in pioneering the arts in the country, and having launched the careers of many actors, is at the heart of its historical significance. Named as the country’s first national theatre, it hosted cultural and social events.

The theater’s rectangular and stepped silhouette showcased Arellano’s affinity for the Beaux-Arts style. Simultaneously, the stylized features and French ornamentations showed his inclination to Art Deco. Arellano intertwined western architectural features with the vernacular, reflecting Art Deco’s intersection of the traditional and the avant-garde.

For instance, the windows of the theater facade were decorated with tiles influenced by Southeast Asian batik patterns. Through sculptors Isabelo Tampico and Francesco Monti, Arellano was able to integrate Filipino motifs into the interior. The ceiling patterns drew inspiration from local flora and fruits, such as mangoes and bananas.

The building exhibits the cultural interaction between a Western architectural style and Filipino architecture, contributing to the early beginnings of Philippine Art Deco.

Related Read: Juan Arellano’s Mastery and His Art Deco Buildings

Rizal Theater

The Rizal Theater was a film and performance venue designed by Architect Juan Nakpil. In the 1960s, he pioneered the use of folded plates as structural shells. His architectural style was marked by defined geometric lines, with the folded plates forming the structural enclosure. The theater’s façade had a slight convex form, including fourteen tapering pilasters.

The material concrete was experimented upon to create sculpture-like structures. For the theater, the building was intentionally made to have an illusion of visual lightness, giving the appearance that it was floating. The building’s canopy stands out in the design as it extends over the entrance. Inside, the venue featured a unique ascending curve in its seating areas.

The theater was envisioned to be a part of the Rizal Memorial Cultural Complex, but the project was later scrapped due to a lack of funding. It was then demolished in the 80s to make way for the Shangri-La Hotel.

The Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) Building

Modernism rose in popularity after the devastation left by World War II. As the state gained newfound independence, the government needed a structure to house the country’s political ambitions. The rehabilitation period in capital cities was motivated by establishing a nationalistic spirit through government edifices. State architecture contributed to the formation of a unified national identity.

For war-damaged cities and municipalities rebuilding their offices, the rushed construction and plans led to the preference for modernism as the architectural solution. Those engaged in postwar construction sought a straightforward approach to architecture. The philosophy of function over form influenced the works of many architects. Structures transitioned into one of restraint, often absent of ornaments in both their interior and exterior.

The Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) Building was one of the first buildings constructed for the buildings program of the New Republic. Designed by Federico Ilustre, the consulting architect for the Bureau of Public Works, its construction was completed in 1957 in Arroceros, Manila.

In his book Ariketekturang Pilipino, Architect Gerard Lico described the GSIS Building as the “intersection between neoclassical and modern aesthetics.” The main structure of the building is a rectangular shape, with pillars and vertical bay windows that make up its imposing façade. The corner of the building consists of a rounded corner tower.

National ambition and state advancement were expressed through simplified geometric shapes and the use of reinforced concrete, steel, and glass. The GSIS Building was among the earliest structures that witnessed the government’s path towards nation-building.

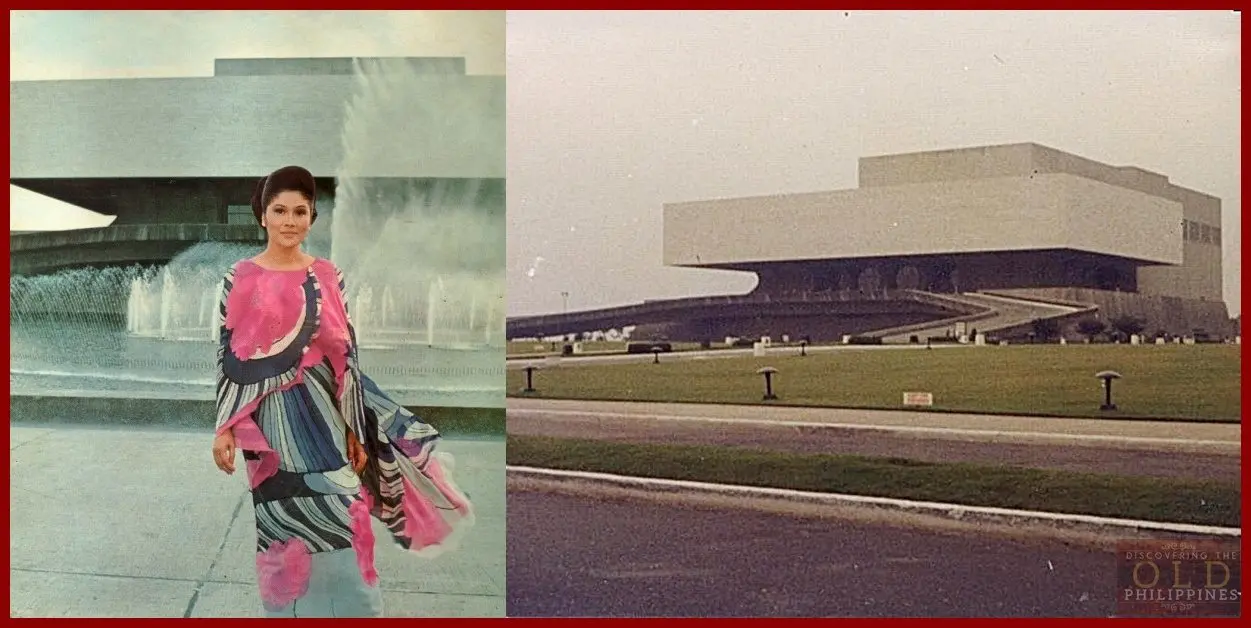

Cultural Center of the Philippines

The Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) was constructed in 1969 to promote the performance and the arts. Situated on reclaimed land, the CCP signaled the beginning of then First Lady Imelda Marcos’ edifice complex and served as a center for Filipino heritage and culture.

The First Lady, an advocate for architecture, was responsible for overseeing the building boom of the 1970s and 80s. The Marcosian ideology centered on an idea of purity in architecture, one without colonial influences—promoting a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era of simplicity and tranquility.

Designed by Leandro Locsin, the architect formed an abstract interpretation of the bahay kubo. Locsin drew characteristics such as the bahay kubo’s visual lightness, open concept, and raised features. His signature brutalist designs embraced the use of rough concrete, brick, and glass, usually described as boxy and sculptural.

The building is composed of a rectangular slab suspended above ground by thin supports, reminiscent of the bahay kubo’s stilts. Introduced by Cresenciano de Castro, an exposed aggregate finish consisting of crushed eggshells was utilized for the building’s exterior. The pool that fronts the building doubles the structure through its water reflection. Famous writer Nick Joaquin described the CCP as Locsin’s “most daring and dramatic sculpture.”

The successful establishment of the CCP prompted a series of other building projects to be constructed under the surveillance of the Marcos administration.

Coconut Palace / Tahanang Pilipino

The Coconut Palace, or Tahanang Pilipino, was constructed in 1978 within the CCP Complex as a state guesthouse for visiting dignitaries. It was commissioned by Imelda Marcos for the upcoming visit of Pope John Paul II in 1981. This invitation was famously turned down by the Pope, believing the place to be too ostentatious, given the widespread poverty of the time.

The Coconut Palace is a structural representation of Marcos’ desire to distance the nation from colonial influences, intentionally building architectural projects that drew inspiration from indigenous practices. Marcos chose Francisco Mañosa due to his active advocacy of Philippine architecture and his direct and distinct execution of vernacular traditions.

The Marcos regime was a proponent of the nation’s vernacular renaissance, with the Coconut Palace being one of the most significant architectural representations. The structure was inspired by traditional features. The double roof of the guesthouse is an octagonal shape resembling a salakot, a traditional Filipino hat. Meanwhile, the swing-out windows are reminiscent of the bahay kubo.

Its construction relied heavily on coconut-derived materials. The structure utilized a total of 2,450 coconut trees. The interior of the guesthouse features a 101-coconut shell chandelier and a dining table adorned with around 40,000 arranged pieces of crushed and polished coconut shells. Even its hexagonal spatial scheme simulated the pattern found in coconut tree trunks.

The project resulted in the invention of a new form of coconut, one that can be used for construction purposes due to its higher resiliency than normal coconut lumber. Named after the former first lady, the Imelda Madera was produced by treating a breed of coconut created by the Philippine Coconut Authority.

Other materials like bamboo, rattan, and capiz shells were also used to further emphasize its Filipino spatial identity. Mañosa continued to promote the return of vernacular concepts and local materials, cementing himself as one of the foundational architects of the neovernacular wave in the country.

The Coconut Palace was constructed at an estimated price of P18 million during a time of economic instability and political turmoil. Ultimately, the Marcos regime leveraged architecture as a crucial tool for political propaganda, fostering a distinct Filipino identity through self-exoticism within its architectural framework.

Related Read: Creativity and Logic: Francisco Mañosa’s Legacy

San Miguel Headquarters

The San Miguel Headquarters was designed by the Mañosa Brothers (Manuel, Jose, and Francisco Mañosa). It was inaugurated on June 2, 1984. The building was a response to the advocacy for architecture to correspond with local climate and culture. Hailed as one of the first examples of “green architecture” in the country, the building drew inspiration from the Banaue Rice Terraces.

Located at the Ortigas Business Center, the building stands out among the other existing structures due to its green-filled architecture. The terraced prism contains angled canopies that control the amount of heat and natural light that enters the building. This design also minimizes energy consumption by letting in as much natural light as possible. Solar panels were later installed on the angled canopies as another tool of energy conservation.

The brothers collaborated with Ildefonso Paez Santos Jr., better known as IP Santos, for the landscaping, which is an integral aspect of the architecture. IP Santos incorporated pocket gardens and ponds, providing workers with areas where they can cool off from the tropical climate.

The integration of natural elements into the design also focused on enhancing the working environment for the employees who would be using the space. A jogging path was included to promote physical activity among staff. Physical activities are also encouraged by the fully-equipped gym and shower room facilities. In addition, the podium level is a sheltered space that serves as the main social hub of the employees. It is adjacent to the large cafeteria that can accommodate around 500 employees. The architecture and landscaping emphasize sustainability and prioritize the well-being of employees.

It has been more than 40 years since the building was constructed. Other businesses soon filled this district, such as the ADB complex and the Shangri-La complexes. However, this building still stands out as one of the only green spaces within an urban area full of tall concrete structures.

Read more: 7 Modern Bahay Kubo Designs Spotlight a Filipino Classic