Ronald Ventura is one of the most recognizable figures in Southeast Asian contemporary art. Since his first solo exhibitions in the 2000s, Ventura has become known for his signature multi-layered paintings. Featuring hyperrealism, cartoons, graffiti, and other recurring motifs, hisworks—from paintings to sculptures—are pluralistic in both form and material. Throughout his career, his art has […]

Filipino Textiles: Magical Weaves of the Mindanao and Sulu People

In every society, clothing indicates a human being’s relationship with the community. It defines their beliefs and celebrates design artistry that speaks of their identity as a distinct group or individual. This is especially so in our pre-industrial societies, where Filipino textiles primarily defined a person’s material value and social status. Before colonization and modernization, the peoples of Mindanao, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi were fierce defenders of their territorial identity. They were also demanding clients of traditional and imported weaving. These symbolized their uniqueness, qualities that are arguably “tracers” of cultural continuity.

Preserving a Dying Tradition

Collected by American ethnographers since the turn of the century, you can find many of these significant examples of clothing in foreign museums. Fortunately, former Senator Nikki Coseteng has championed traditional weaving as a source of cultural pride among Filipinas. She compiled an extensive collection of Filipino textiles from different areas of the country, rare examples of the high art that traditional weaving has achieved. In addition, Coseteng published a scholarly coffee table book in 1991. Sinaunang Habi, written by Marian Pastor Roces, discusses the importance of the dying tradition of Filipino weaving.

Lumad and Moro

We can divide the traditional peoples of Mindanao and Sulu into two main groups. There’s the polytheistic lumad peoples of northeastern, central and southwestern Mindanao. These include the Bagobo, B’laan, Mandaya, Mansaka, Talaandig, and Kalagan-Tagakaolo.

The other group are the Islamized Moro peoples of the northwestern/western side of Mindanao island and the Sulu/Tawi-Tawi archipelagoes. Among them are the Maranaw, Maguindanaw, Ilanun, Subanon, Yakan, Tausug, and Sama-Badjao. You can differentiate the motifs of these two main groups between. The lumads have highly stylized human and animal figures. The Moros used abstracted geometric shapes with curvilinear patterns.

Weaving Techniques

There are also two main techniques for producing designs in these fabrics, shared by both groups. There’s the bë-bëd or ikat method of reserve dyeing; and the panayan or ansif method of embroidery and bead stitching. Notwithstanding the technique of decoration, all the peoples of Mindanao (indeed, all non-Christianized Filipinos) rely on a common form of assembling the warps and wefts through the back-strap loom. It’s a system of threads suspended on a set of wooden sticks, braced to the wearer’s back, and tied to a post—usually in the raised house’s silong.

Traditional weaving was, therefore, a supremely women’s art. It relied on their capacities for hard work, encoding knowledge, and relaying tradition. They even recited dreams into coherent and mathematically excellent weaving design.

Colors, Patterns, and Motifs

The color sensibility is the first thing that hits you between the two general traditions of Moro and lumad. The former is more riotous, with gaudy contrasts of red, yellow, black, green, purple, and white. The latter attached to a narrower range, from scarlets to maroons, bleached whites, browns, blacks, and more recently, blues.

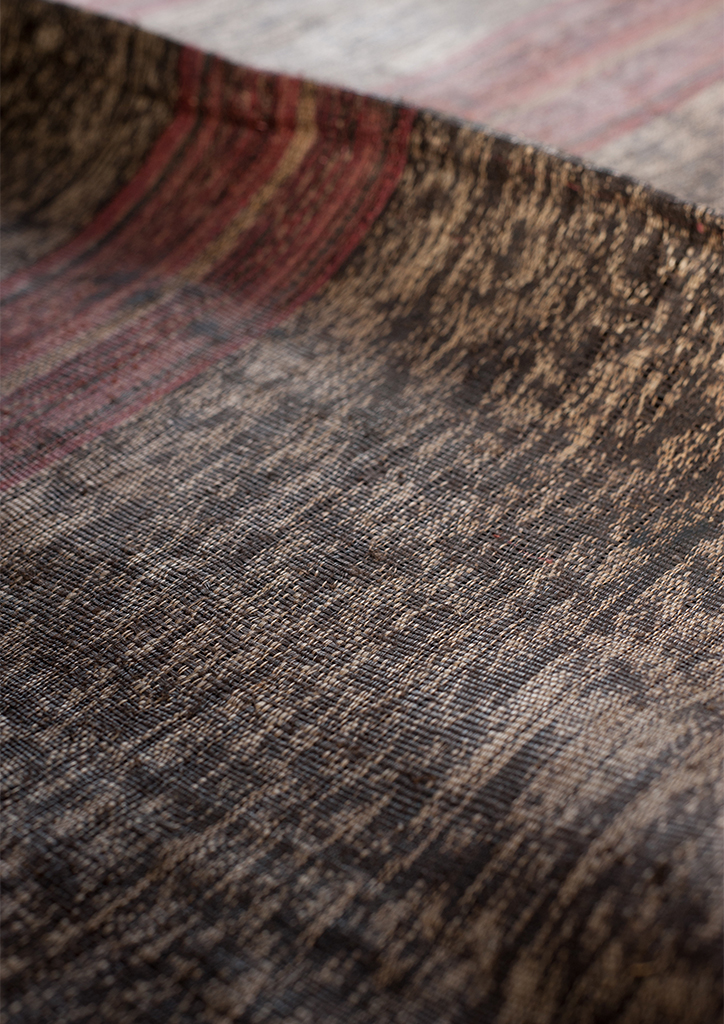

There is also a more pronounced abstract geometry among the Moros. Weavers use diamonds, chevrons, crosses, triangles, and their distinct okir curves. Whereas the lumad exhibits a wide range of human and animal figures, primarily the crocodile (buwaya) or monitor lizard. Perhaps the most spectacular examples from each group are the Maranao’s silk landap malong and the T’boli t’nalak. The landap features golden yellow squares bordered by bands of green, red, and purple. The t’nalak showcases abaco-woven bleached white patterns of crocodiles and human figures set against a deep brown. Its large diamonds and red bands create an effect resembling a python’s glistening skin from afar.

The austere deep brown against red and yellow supplementary embroidery pattern identifies this blouse as that of the T’boli kegal. The textiles feature human figures holding hands, placed among larger sections with diamond-shaped borders. These borders also contain richly geometric medallions with floral or animal designs that speak to the people’s well-known animistic beliefs. This is despite living near their Muslim neighbors.

Conserving Our Precious Traditions

Indeed, to talk about each Mindanao group’s unique textile designs, terms, and methods would fill up entire encyclopedia volumes. For now, you can view examples of the Nikki Coseteng Collection in the pages of Roces’ book to re-educate audiences about the power of tradition and native artistry. It demands continuation and reincarnation, before forgetfulness and ignorance destroy these most fragile of Filipino textiles and cultural design assets forever.

This article was first published in BluPrint Volume 5 2013. Edits made for BluPrint online.

Photographed by Greg Mayo

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Weaving in the Philippines is a traditional craft of creating fabrics and items using natural fibers like abaca, piña, cotton, and bamboo, often tied to cultural identity.

Popular weaving traditions include abaca weaving in Mindanao, piña weaving in Aklan, inabel weaving in Ilocos, and T’nalak weaving by the T’boli of South Cotabato.

T’nalak weaving from the T’boli people is often regarded as the most iconic, known for its abaca fibers and symbolic patterns inspired by dreams.

Weaving in the Philippines dates back to pre-colonial times, practiced by various indigenous groups who used natural fibers to create textiles for clothing and rituals.

Traditional weaving involves hand-looming natural fibers into textiles like inabel, hablon, piña, and t’nalak, often reflecting cultural symbols and community heritage.