The Romanesque Revivalist Jaro Cathedral and its ‘unfaithful’ additions

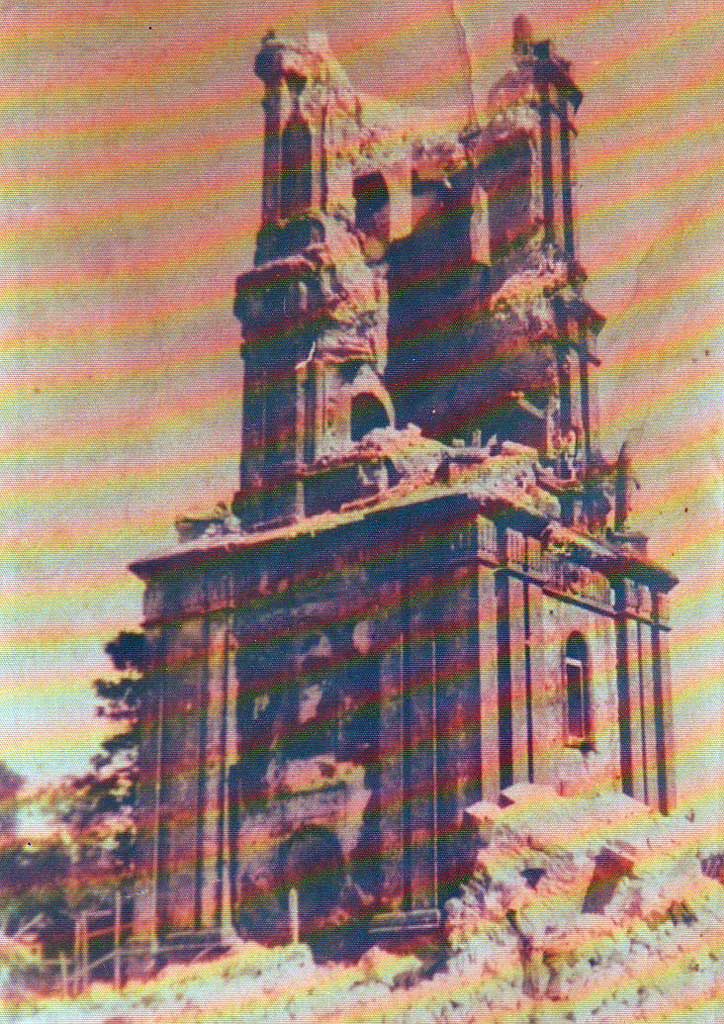

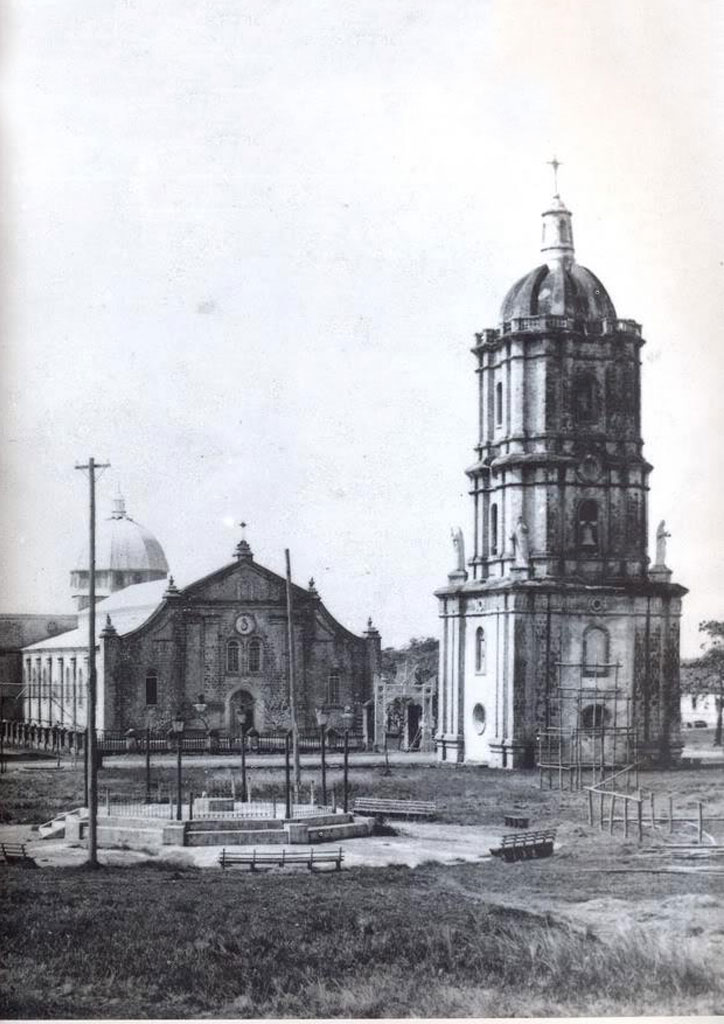

The Jaro Cathedral has been victim to several unfaithful additions since 1956, eight years after the Lady CayCay earthquake, the second strongest in the country, damaged the church and its belfry in January 1948. The cathedral, completed in 1874 under Fr. Mariano Cuartero, features a Romanesque Revivalist design.

Measuring 46 meters long and 16 meters wide, the church has a cruciform plan with a central nave and side aisles separated by two rows of columns made of stone and landrillo (bricks). A dome sits at the crossing where the transept, nave, and chancel meet. In January 1951, Jaro was made an archdiocese under Archbishop Jose Maria Cuenco, who supervised the repair and reinforcement of the cathedral and belfry damaged by the quake.

It was during this time that major interventions unsympathetic to the church’s architecture appeared. Cuenco ordered the addition of a grand portico on the northeast façade that doubles as a porte-cochère, a staple in many English and American mansions at the turn of the 19th century. A decade later in 1961, he authorized the construction of two bell towers with a mix of Neo-Gothic and Neo-Classical motifs on both sides of the Church.

The coup de grace came when Cuenco’s overeager successors, prompted by the visit of Pope John Paul II on February 21, 1981, oversaw the construction of Neo-Classical twin staircases leading to a permanent balcony on top of the port-cochère. From there, the pontiff celebrated mass and personally crowned the 16th-century limestone image of the Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria (Our Lady of the Candles) proclaiming her Patroness of the Western Visayas. For the faithful, the unfaithful construction has become a pilgrimage site, a memorial shrine to commemorate the historic event and honor Mary.

READ MORE: Old Jaro city hall restored and now National Museum satellite

What’s the issue?

The Venice Charter of 1964 states that additions should “not detract from the interesting parts of the building, its traditional setting, the balance of its composition and its relation with its surroundings.” Take the twin colonnades of St. Peter’s Square in Rome, which were added three to four decades after St. Peter’s Basilica was completed in the early 1600s. They have been valued and conserved because they don’t compete with the basilica. Instead, they complement the towering church with low but expansive forecourt from which pilgrims can approach the steps of St. Peter’s with a sense of awe and adoration. The Tuscan colonnades, a simpler version of the Doric, rightly defer to the monumental, opulent, and majestic Renaissance basilica.

Had the additions to Jaro Cathedral been similarly respectful of the church, they might have been worth conserving. Regrettably, the Neo-Gothic Neo-Classical bell towers are uncalled for and clash with the church’s Romanesque aesthetic, ruining its formerly low but graceful silhouette. Worse, the dense concrete belfries are grossly incompatible with the ancient stones of the cathedral, and impose loads dangerously heavy for the light, porous, and centuries old coral stone walls to carry.

READ MORE: Jaro’s Casa Mariquit, a bahay na bato as graceful as its namesake

Meanwhile, the 1980s Neo-Classical balcony with the twin staircases abuts the church’s principal façade and sits right smack in the middle so as to eclipse the church’s 142-year old rose window. None of the additions are even faithful representatives of their periods.

In his article in BluPrint published five years ago, architect Joseph Javier provides a lucid description of the towers and the balcony. “Jaro Cathedral’s two concrete Gothic steeples installed in the Sixties seem to be pushing out from under the earth, through the bowels of a helpless Romanesque basilica. It reminds one of an extraterrestrial host. One may even speculate that the two spires were intended to ‘keep up’ with the neighboring Molo Church, whose Gothic silhouette has always been more impressive. The ‘neo-‘neo-classic’ pontifical balcony with its garland of stairs appears to be playing patintero with the cathedral façade in a game of design one-upmanship. The shrine of Our Lady of Candles looks like a plastic nose planted on the church’s weathered sandstone face.”

The Narra Document of 1994, which builds on the Venice Charter, recognizes that “conservation of cultural heritage in all its forms and historical periods is rooted in the values attributed to the heritage.”

The judgment of such values varies from culture to culture and thus “heritage properties must be considered and judged within the cultural contexts to which they belong.” It is not surprising that, despite the hideous additions, the parishioners feel attached to and protective of the cathedral, particularly the balcony shrine. After all, no less than the Vicar of Christ—now a saint—ascended its steps and joined God’s flock gathered in Jaro in 1981.

As the principal stakeholders for whom the cathedral is being conserved, the people of Jaro have imposed a cultural and social value upon the intrusive shrine.

READ MORE: Spanish, Chinese, Muslim, and Filipino motifs in Casa Sanson y Montinola in Iloilo

The situation, therefore, presents a nagging dilemma. Should the towers and the balcony be removed to bring the cathedral back to its authentic state at risk of offending sensibilities? Prudence and respect for history and integrity require that they should, sooner rather than later.

The continued tolerance of such traditions has set a dangerous precedent for other historical assets. It constitutes tacit approval for priests wanting their personal stamp upon the church (as is their wont), to implement similar additions incongruous to the building’s original design and without regard for basic aesthetic principles such as harmony, scale, and proportion. Worse, they would get away with frivolous additions under some imagined noble or practical intention. As Javier pointed out in his article, “Would the same kind of commemorative construction for a papal visit be acceptable, say, for Paoay Church?”

Furthermore, for a venue for contemplation, the balcony clearly wasn’t well thought out. Does a shrine overlooking a busy, noisy, and polluted street make for a venerable setting for a solemn, prayerful reflection and augment the devotees’ experience of the divine? If anything, it only presents practical challenges for its intended users, its stakeholders. Should we subject the sick and the elderly—those the Church considers to be in most need of mercy—to an unmerciful climb of more than 30 steps to an open balcony so they can pray at the foot of Our Lady? Is the glass enclosure enough to protect the 16th-century Marian image, the church’s most precious treasure, against thieves, vandals, and typhoons?

The Iloilo Cultural Heritage Foundation, constituted years after the porte-cochère was added, is on record that the balcony and the twin bell towers should go. Like Javier, they consider the additions a “folly, a pimple or a boil on the face of the cathedral.” They are right. After years of calling out for the demolition of the unfaithful additions, it’s time the foundation moved forward and consulted with church administrators and the community to work out a sensible alternative; one that allows the devotion to the Patroness of the Western Visayas, which started with the Pope’s visit, to continue in more hospitable and meditative environs, without conflicting with and endangering what remains of the 17th century structure. The Ilonggos are a perceptive people who care deeply about their heritage assets. As in the case of the Lizares Mansion, they have demonstrated a capacity to put the preservation of their cultural heritage treasures above customs they have only recently formed.![]()

READ MORE: The grand Beaux-Arts style now even clearer in Iloilo’s Lizares mansion

Original article first appeared in BluPrint Special Issue 3 2016. Edits were made for Bluprint online.

Photographed by Mark Jacob and Ed Simon