In urban development and public spaces, architects, interior designers, and landscape architects play pivotal roles in crafting environments that foster safety, inclusivity, and community engagement. These professionals are tasked not only with the aesthetics and functionality of spaces but also with ensuring that these spaces become vibrant, interactive, and sustainable parts of the community fabric. […]

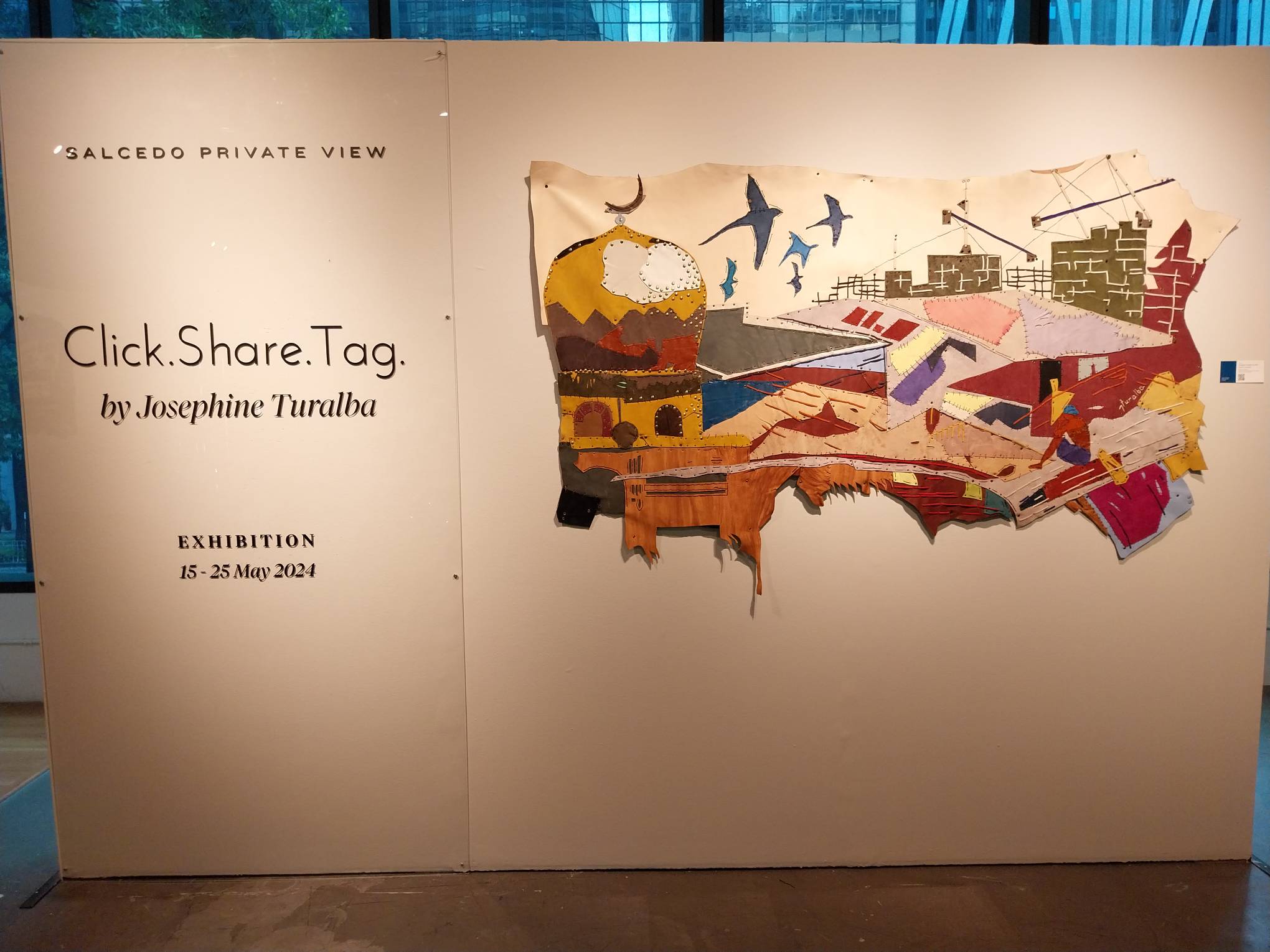

Josephine Turalba Showcases Her Tapestry of Life ‘Click. Share. Tag.’

Click. Share. Tag., the leather cut-out tapestry made by artist Josephine Turalba, is being exhibited at Salcedo Auctions from May 15 until May 25. Turalba originally made the tapestry for the Cultural Center of the Philippines, filling a large wall with stitched-together leather cut-outs.

The tapestry itself is made of smaller pieces that tell their own stories based on Turalba’s travels. (“They’re not actually small, they’re still large but smaller than the big thing,” Turalba said when describing each individual piece). This was done for logistical reasons, as a way of allowing it to keep being exhibited in other places in the future.

“[If] they were one big carpet, who would have the wall to put that? So I said, ‘really, make small pieces, small stories of each, and then collage it and stitch it together into one big story.’ So the challenge was to make a story of the whole thing but yet at the same time to make [a] story per panel.”

In BluPrint’s interview with the artist, we discussed how her travels inspired the work, her attempts to create a broader story with her art, and dealing with the politics of colonial and personal trauma.

Echoing Her Travels of the World

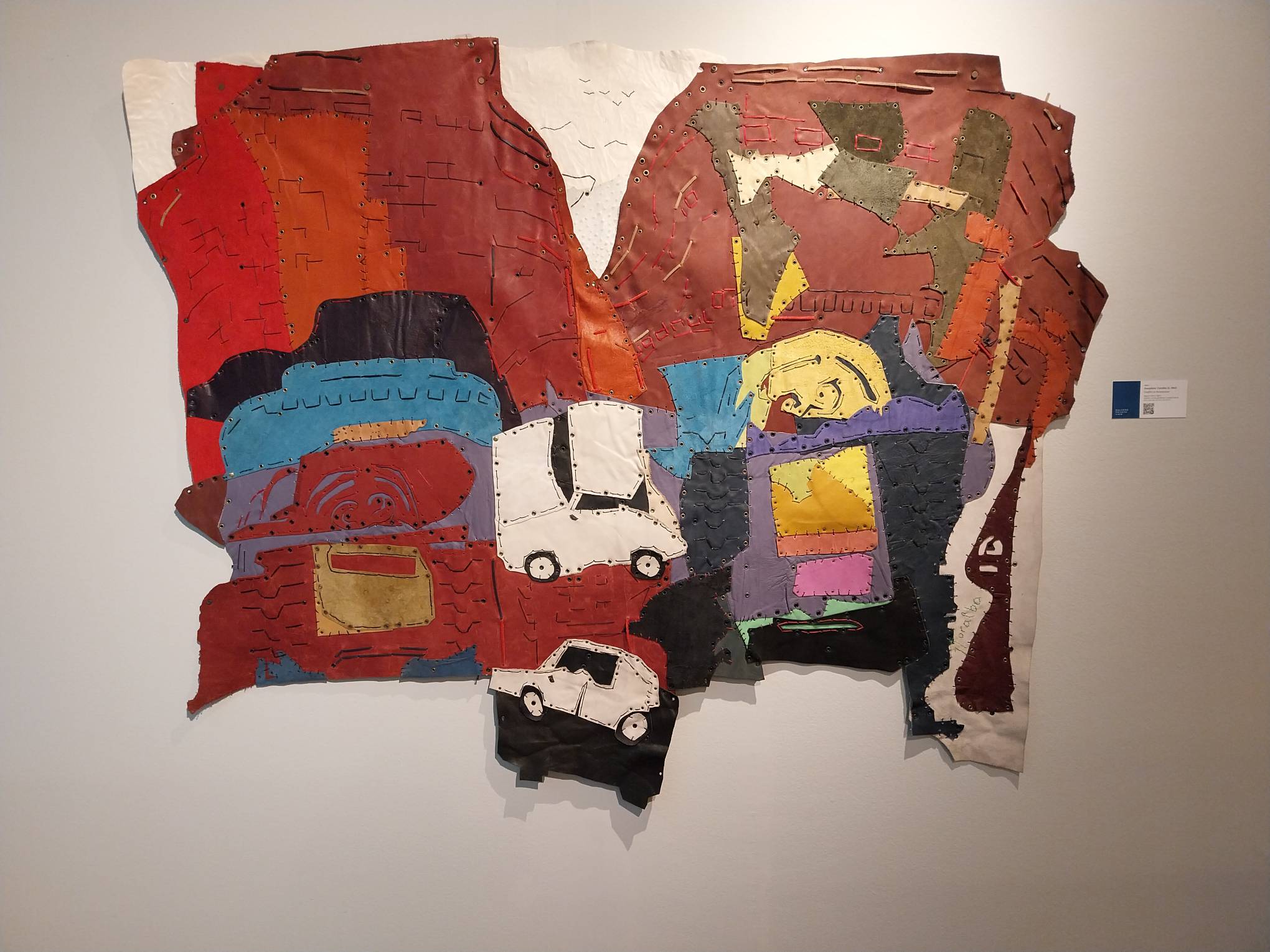

Click. Share. Tag. as a work is expansive. The cut-up leather portions showcased in Salcedo Auctions encompass the size of a large canvas, multiple feet in length on each side. Imagining it stitched together would create this monumental work the size of a mural. Turalba describes it as a “big carpet” that she broke up into multiple parts to make it easier to install.

Each piece of Turalba’s work tells a story about her travels and experiences around the world, from Boston to Istanbul to Manila. Despite the universal sprawl of her work, each part of the tapestry connects closely to one another, and the work achieves something close to a multi-narrative story like Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Babel: criss-crossing ideas that span language and cultural barriers.

Her framing story for the piece is the photographer prominently put in the front of the tapestry. As the title implies, it can be interpreted as a collision of different worlds, with the photographer inviting us to see beyond the lenses of the camera—seeing the world through the eyes of the audience.

“[The work is] talking about how we, in our minds, need to stitch these fragmented memories that we have. Whether it’s physical travel or travel through our mobile applications, it still fragments our mind,” she said.

Fragments Into A Whole

She found similarities with each city, linking the brownstones of Boston to the streets of Manila, or the mosques of Istanbul to the similarly-ubiquitous churches in Manila. It’s an intertwining culture, made easier by technologies of the present, that allows us to see the parallels of existence wherever we might be.

“I have an experience [of] ‘sometimes I’m here, sometimes I’m somewhere else.’ Mentally. Psychologically also,” she said. “Because you saw it on your phone. Sometimes you’re in Gaza, and sometimes you’re somewhere else, in New York. And then you’re in Tondo or you’re in Marikina or you’re in Quezon, Lucban. So, yeah, I’m just trying to stitch all of these together in the studio and in the story.”

The Blisters of Colonialism

Seeing the multicultural focus of her work, it’s not surprising that Josephine Turalba utilizes her time and artistry to talk about post-colonial topics. Stemming from dealing with her personal trauma of her father’s death through her art, it expanded towards the collective trauma of the Filipino as the country wrestles with its past.

“If you’re in the US, for example, who are you there as a Filipino? You’re only one of those that we colonized. You’re not white, right? We’re not white. So we’re brown,” she started.

“So really, there’s a difference. It started making me look at things that are connected and look into historical trauma, like the post-colonial trauma that has left with us. So our colonial legacy, for example, our colonial mentality: how does it still affect us today? I mean, yes, we don’t have any more of the wars, they’re not in our land, but yes, why are we full of ads that make us look white?”

Turalba, who studied psychology during her undergraduate years, connected the trauma of the country to the way we react to hot button topics like the West Philippine Sea or charter change or similar topics that have connections, however tenuous, to our imperialist past.

“[I’ve] been following all the news, but now it’s really been [a] hot topic. Why are we reacting this way? Why? Because, again, of our historical trauma from colonialism. We don’t wanna be colonized anymore, we don’t—we want our voices to be heard.”

Performance of the Past

Being a Filipino artist who has presented her work around the world, Josephine Turalba carried a lot of stories regarding her experiences with different cultures engaging with her work. The most interesting aspect of it is the varying reactions of people to her performance art, which involves her donning a wardrobe made of spent bullet casings.

“[The] one in New York, I went to the Highline; they knew, they were like, ‘oh you’re doing performance art! Oh, what are these? These are bullets? Oh! What are you talking about? War?’ I mean, they’re so well-informed,” she began.

“But here in Manila, when I went down the streets, they were like, ‘ahh, ang ganda-ganda mo.’ And then there was one area outside Quiapo Church, napadpad ako sa may vendors. Tapos biglang lumabas yung arm ko na gumanon. Tapos binigyan ako ng pera. They gave me—I earned about a dollar, like ten pesos, twenty pesos.

“And then they like to touch. There was this lady who was like, ‘wow, pwede bang [isuot]?’ So I gave her my hat. She wore it. And the other guy is like an OFW, he was lining up for the OFW and he was like, ‘kailangan ito sa Mindanao kasi sa Mindanao, sa tingin nila ang buhay ng tao parang manok lang.’ And then he wanted to wear it, and so I made him wear it.”

Progressing Her Art Forward

Her interest in performance art came about as a natural progression of her body art, seeking something wearable as a practice of “cleansing” through the tools that used to do harm or did harm to her.

“I’m trying to protect myself—I guess all of these works subconsciously, but eventually I realized that in trying to put something to protect yourself but this is the cause of the harm, the destruction. So what does that—I’m working with these juxtapositions,” she said.

As she moves forward in her career, exploring new ideas, she hopes to still be able to engage with the world by telling the stories of the marginalized—whether it’s dealing with her own trauma or scrutinizing the collective traumas of our society.

“I feel that, as an artist, I speak for myself but also for my people. I get drawn to topics like that, the ones that don’t have a voice. Those are my topics, a lot of my themes, storytelling about those,” she said.

Related reading: Dissecting Our Use of Technology in Art with Comilang and Speiser